Classics 2 Program Notes Conga-Line in Hell Miguel Del

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Premium Blend: Middle School Percussion Curriculum Utilizing Western and Non-Western Pedagogy

Premium Blend: Middle School Percussion Curriculum Utilizing Western and Non-Western Pedagogy Bob Siemienkowicz Winfield School District 34 OS 150 Park Street Winfield, Illinois 60190 A Clinic/Demonstration Presented by Bob Siemienkowicz [email protected] And The 630.909.4974 Winfield Percussion Ensembles ACT 1 Good morning. Thank you for allowing us to show what we do and how we do it. Our program works for our situation in Winfield and we hope portions of it will work for your program. Let’s start with a song and then we will time warp into year one of our program. SONG – Prelude in E minor YEAR 1 – All those instruments The Winfield Band program, my philosophy has been that rhythm is the key to success. I tell all band students “You can learn the notes and fingerings fine, but without good rhythm, no one will understand what you are playing.” This is also true in folkloric music. Faster does not mean you are a better player. How well you communicate musically establishes your level of proficiency. Our first lessons with all band students are clapping exercises I design and lessons from the Goldenberg Percussion method book. Without the impedance of embouchure, fingerings and the thought of dropping a $500 instrument on the floor, the student becomes completely focused on rhythmic study. For the first percussion lesson, the focus is also rhythmic. Without the need for lips, we play hand percussion immediately. For the first Western rudiment, we play paradiddles on conga drums or bongos (PLAY HERE). All percussion students must say paradiddle while they play it. -

A Musical Analysis of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumming

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2019 Meaning Beyond Words: A Musical Analysis of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumming Javier Diaz The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2966 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] MEANING BEYOND WORDS: A MUSICAL ANALYSIS OF AFRO-CUBAN BATÁ DRUMMING by JAVIER DIAZ A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, The City University of New York 2019 2018 JAVIER DIAZ All rights reserved ii Meaning Beyond Words: A Musical Analysis of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumming by Javier Diaz This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor in Musical Arts. ——————————— —————————————————— Date Benjamin Lapidus Chair of Examining Committee ——————————— —————————————————— Date Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee Peter Manuel, Advisor Janette Tilley, First Reader David Font-Navarrete, Reader THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Meaning Beyond Words: A Musical Analysis of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumming by Javier Diaz Advisor: Peter Manuel This dissertation consists of a musical analysis of Afro-Cuban batá drumming. Current scholarship focuses on ethnographic research, descriptive analysis, transcriptions, and studies on the language encoding capabilities of batá. -

PROGRAM NOTES Franz Liszt Piano Concerto No. 2 in a Major

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Franz Liszt Born October 22, 1811, Raiding, Hungary. Died July 31, 1886, Bayreuth, Germany. Piano Concerto No. 2 in A Major Liszt composed this concerto in 1839 and revised it often, beginning in 1849. It was first performed on January 7, 1857, in Weimar, by Hans von Bronsart, with the composer conducting. The first American performance was given in Boston on October 5, 1870, by Anna Mehlig, with Theodore Thomas, who later founded the Chicago Symphony, conducting his own orchestra. The orchestra consists of three flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, cymbals, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-two minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Liszt’s Second Piano Concerto were given at the Auditorium Theatre on March 1 and 2, 1901, with Leopold Godowsky as soloist and Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given at Orchestra Hall on March 19, 20, and 21, 2009, with Jean-Yves Thibaudet as soloist and Jaap van Zweden conducting. The Orchestra first performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on August 4, 1945, with Leon Fleisher as soloist and Leonard Bernstein conducting, and most recently on July 3, 1996, with Misha Dichter as soloist and Hermann Michael conducting. Liszt is music’s misunderstood genius. The greatest pianist of his time, he often has been caricatured as a mad, intemperate virtuoso and as a shameless and -

Hofmannsthal JAHRBUCH· ZUR EUROPÄISCHEN MODERNE 5/1997

HofMANNSTHAL JAHRBUCH· ZUR EUROPÄISCHEN MODERNE 5/1997 Im Auftrag der Hugo von Hofmannsthal-Gesellschaft herausgegeben von Gerhard Neumann . Ursula Renner Günter Schnitzier . Gotthart Wunberg Rombach Verlag Freiburg Hugo von Hofmannsthal- Mechtilde Lichnowsky Briefwechsel Herausgegeben von Hartmut Cellbrot und Ursula Renner Blicke, Hände, Geschriebenes, Handschrfll, Gedichte - es ist ja alles ungffdhr darselhe. HofmannsthaI an Mechthilde Lichnowsky Hugo von Hofmannsthal lernte die Fürstin und spätere erfolgreiche Schriftstellerin Mechtilde Lichnowsky Anfang 1909 in Berlin kennen. Am 18. Februar schreibt er an seinen Vater: Heute trinken wir Thee in dem neuen ganz amerikanisch prunkvollen Es planade-Hotel bei der Fürstin Lichnowsky, geb. Arco, die eine ganz char mante junge Frau ist. Wahrscheinlich wurden schon bald Briefe mit Verabredungen ausge tauscht. Die ersten gesichert datierten Briefe der hier veröffendichten Korrespondenz stammen aus dem Frühjahr 1910.1 Hofmannsthal und Mechtilde Lichnowsky begegneten sich zumeist im Rahmen der Pre mieren von Hofmannsthals Stücken und im Ambiente der vornehmen Berliner Salons der Gräfm Harrach, Schwiegermutter von Mechtilde Lichnowskys Schwester Helene, und Cornelia Richters, der Tante von Hofmannsthals Freund Leopold von Andrian, in denen Aristo kratie, Großbürgertum, Intellektuelle und Künsder vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg miteinander Umgang pflegten. Hofmannsthal, der die Ber liner Gesellschaft in »Leute, Leute, Leute« und »die paar Menschen«, welche ihm wichtig waren, unterteilte, fand in der Gräfm Lichnowsky nicht nur eine jener schönen kultivierten Frauen, die ihn anzogen, sondern auch einen Menschen, mit dem er sich im Gespräch austau schen konnte und auf dessen Urteil er Wert legte. Den Berliner Begegnungen mit allen fehlt es an Ruhe und Consequenz. Fast habe ich dann lieber, wenn ich einen Menschen nur einmal sehe, wie den al- 1 Die Briefe Hofmannsthals befinden sich im Zemsky archiv v Opave, Ceska repu blika. -

Commemorative Concert the Suntory Music Award

Commemorative Concert of the Suntory Music Award Suntory Foundation for Arts ●Abbreviations picc Piccolo p-p Prepared piano S Soprano fl Flute org Organ Ms Mezzo-soprano A-fl Alto flute cemb Cembalo, Harpsichord A Alto fl.trv Flauto traverso, Baroque flute cimb Cimbalom T Tenor ob Oboe cel Celesta Br Baritone obd’a Oboe d’amore harm Harmonium Bs Bass e.hrn English horn, cor anglais ond.m Ondes Martenot b-sop Boy soprano cl Clarinet acc Accordion F-chor Female chorus B-cl Bass Clarinet E-k Electric Keyboard M-chor Male chorus fg Bassoon, Fagot synth Synthesizer Mix-chor Mixed chorus c.fg Contrabassoon, Contrafagot electro Electro acoustic music C-chor Children chorus rec Recorder mar Marimba n Narrator hrn Horn xylo Xylophone vo Vocal or Voice tp Trumpet vib Vibraphone cond Conductor tb Trombone h-b Handbell orch Orchestra sax Saxophone timp Timpani brass Brass ensemble euph Euphonium perc Percussion wind Wind ensemble tub Tuba hichi Hichiriki b. … Baroque … vn Violin ryu Ryuteki Elec… Electric… va Viola shaku Shakuhachi str. … String … vc Violoncello shino Shinobue ch. … Chamber… cb Contrabass shami Shamisen, Sangen ch-orch Chamber Orchestra viol Violone 17-gen Jushichi-gen-so …ens … Ensemble g Guitar 20-gen Niju-gen-so …tri … Trio hp Harp 25-gen Nijugo-gen-so …qu … Quartet banj Banjo …qt … Quintet mand Mandolin …ins … Instruments p Piano J-ins Japanese instruments ● Titles in italics : Works commissioned by the Suntory Foudation for Arts Commemorative Concert of the Suntory Music Award Awardees and concert details, commissioned works 1974 In Celebration of the 5thAnniversary of Torii Music Award Ⅰ Organ Committee of International Christian University 6 Aug. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op

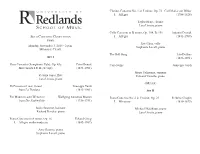

Clarinet Concerto No. 1 in F minor, Op. 73 Carl Maria von Weber I. Allegro (1786-1826) Taylor Heap, clarinet Lara Urrutia, piano Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104, B. 191 Antonin Dvorák SOLO CONCERTO COMPETITION I. Allegro (1841-1904) Finals Xue Chen, cello Monday, November 3, 2014 - 2 p.m. Stephanie Lovell, piano MEMORIAL CHAPEL The Bell Song Léo Delibes SET I (1836-1891) Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op. 43a Peter Benoit Caro Nome Guiseppe Verdi Movements I & II (excerpt) (1834-1901) Mayu Uchiyama, soprano Victoria Jones, flute Edward Yarnelle, piano Lara Urrutia, piano - BREAK - Di Provenza il mar, il suol Giuseppe Verdi from La Traviata (1813-1901) SET II Ein Madehen oder Weibchen Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21 Frédéric Chopin from Die Zauberflöte (1756-1791) I. Maestoso (1810-1849) Justin Brunette, baritone Michael Malakouti, piano Richard Bentley, piano Lara Urrutia, piano Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 Edvard Grieg I. Allegro molto moderato (1843-1907) Amy Rooney, piano Stephanie Lovell, piano Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle Charles Gounod ABOUT THE CONCERTO COMPETITION from Roméo et Juliette (1818-1893) Beginning in 1976, the Concerto Competition has become an annual event Cruda Sorte Gioacchino Rossini for the University of Redlands School of Music and its students. Music from L’Ataliana in Algeri (1792-1868) students compete for the coveted prize of performing as soloist with the Redlands Symphony Orchestra, the University Orchestra or the Wind Jordan Otis, soprano Ensemble. Twyla Meyer, piano This year the Preliminary Rounds of the Competition took place on Friday, October 31st and Saturday, November 1st. -

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Wolfgang Mozart – Piano Concerto No. 20 in D Minor, K. 464 Born January 27, 1756, Salzburg, Austria. Died December 5, 1791, Vienna, Austria. Piano Concerto No. 20 in D Minor, K. 464 Mozart entered this concerto in his catalog on February 10, 1785, and performed the solo in the premiere the next day in Vienna. The orchestra consists of one flute, two oboes, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani, and strings. At these concerts, Shai Wosner plays Beethoven’s cadenza in the first movement and his own cadenza in the finale. Performance time is approximately thirty-four minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Mozart’s Piano Concerto no. 20 were given at Orchestra Hall on January 14 and 15, 1916, with Ossip Gabrilowitsch as soloist and Frederick Stock conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on March 15, 16, and 17, 2007, with Mitsuko Uchida conducting from the keyboard. The Orchestra first performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on July 6, 1961, with John Browning as soloist and Josef Krips conducting, and most recently on July 8, 2007, with Jonathan Biss as soloist and James Conlon conducting. This is the Mozart piano concerto that Beethoven admired above all others. It’s the only one he played in public (and the only one for which he wrote cadenzas). Throughout the nineteenth century, it was the sole concerto by Mozart that was regularly performed—its demonic power and dark beauty spoke to musicians who had been raised on Beethoven, Chopin, and Liszt. -

Percussion Quartet 1.Mus

JULIÁN________________ BRIJALDO CONGANESS for Percussion Quartet www.julianbrijaldo.com [email protected] CONGANESS 5:00 INSTRUMENTATION Percussion I: Bongos Conga drum Tumbadora Percussion II: Vibraphone Marimba 4 Tom-toms Crash cymbal, Splash cymbal & China cymbal Percussion III: Vibraphone Marimba 4 Tom-toms Crash cymbal, Splash cymbal & China cymbal* Percussion IV: Glockenspiel Vibraphone 3 Timpani: 32,'' 26,'' 23'' * The percussion sets share intruments (See the suggested stage diagram) Performance Notes: . Percussion I has the leading role throughout the piece. It should not be overpowered by the other instruments at any moment. The tempo markings in parentheses are approximated. Ideally, the rhythmic flow should feel flexible. Any fermata should not last more than 5 seconds. The individual parts include an instrumental glossary. Duration up to the performers Square fermata: Duration in seconds is notated above the symbol Roll accelerando or ritardando independentely from the tempo indications for the ensemble. Program Notes: by Catalina Villamarín What makes a conga drum what it is? What gives it its distinctive round, earthy sound? Would it be possible to turn any instrument into a conga drum? CONGANESS plays with these questions, and sets out to make a conga drum out of the combination of all the instruments in this percussion quartet. The foundation of CONGANESS was the spectrographic analysis of the four strokes found in a conga-drum salsa pattern: a tumbadora open stroke, a conga-drum open stroke, a conga-drum slap stroke and a conga-drum muffled stroke. The most prominent frequencies of each of these sounds were approximated to the closest pitches available, becoming the palette of sounds with which the piece was built. -

A Study of Tyzen Hsiao's Piano Concerto, Op. 53

A Study of Tyzen Hsiao’s Piano Concerto, Op. 53: A Comparison with Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lin-Min Chang, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2018 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Steven Glaser, Advisor Dr. Anna Gowboy Dr. Kia-Hui Tan Copyright by Lin-Min Chang 2018 2 ABSTRACT One of the most prominent Taiwanese composers, Tyzen Hsiao, is known as the “Sergei Rachmaninoff of Taiwan.” The primary purpose of this document is to compare and discuss his Piano Concerto Op. 53, from a performer’s perspective, with the Second Piano Concerto of Sergei Rachmaninoff. Hsiao’s preferences of musical materials such as harmony, texture, and rhythmic patterns are influenced by Romantic, Impressionist, and 20th century musicians incorporating these elements together with Taiwanese folk song into a unique musical style. This document consists of four chapters. The first chapter introduces Hsiao’s biography and his musical style; the second chapter focuses on analyzing Hsiao’s Piano Concerto Op. 53 in C minor from a performer’s perspective; the third chapter is a comparison of Hsiao and Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concertos regarding the similarities of orchestration and structure, rhythm and technique, phrasing and articulation, harmony and texture. The chapter also covers the differences in the function of the cadenza, and the interaction between solo piano and orchestra; and the final chapter provides some performance suggestions to the practical issues in regard to phrasing, voicing, technique, color, pedaling, and articulation of Hsiao’s Piano Concerto from the perspective of a pianist. -

Harmonic Analysis of Mallet Percussion by Max Candocia Goals

Harmonic Analysis of Mallet Percussion By Max Candocia Goals • Basic understanding of sound waves and mallet percussion • Understand harmonic analysis • Understand difference in sounds of different mallets and striking location Marimba Vibraphone Recording: Vermont Counterpoint, Nathaniel Bartlett Recording: La Fille Aux Cheveux de Lin, Ozone Percussion Ensemble Photo courtesy of vichitex.com Photo courtesy of woodbrass.com Xylophone Recording: Fantasy on Japanese Wood Prints Photo courtesy of onlinerock.com Sound Waves • Vibrating medium (ie. Air, water, ground) • Longitudinal • Harmonics – Sinusoidal Components Sine: Sawtooth: Images courtesy of Wikipedia Qualities of Harmonics • Frequency – Cycles per second (Hertz); determines pitch Photo courtesy of Wikipedia • Amplitude – Power of wave; determines loudness Photo courtesy of physics.cornell.edu • Phase – Location of harmonic relative to other harmonics Photo courtesy of 3phasepower.org Harmonic Analysis Harmonics of Kelon xylophone struck in center with hard rubber mallet Vibraphone HarmonicsDry: Wet: Instrument Mallet Location # Harmonics H1 dB H2 dB H3 dB H4 dB H5 dB Vibraphone Black Dry 5 6 19 0.8 13 3 Vibraphone Black Wet 2 16 1.1 Vibraphone Red Dry 3 22 3.5 1.5 Vibraphone Red Wet 1 1 Vibraphone White Dry 4 16 0.5 9 0.6 Vibraphone White Wet 2 25 1.5 Xylophone Harmonics Instrument Mallet Location # Harmonics H1 Freq H2 Freq H3 Freq H4 Freq H5 Freq Xylophone Hard Rubber Center 4 886.9 1750 2670 5100 Xylophone Hard Rubber Edge 4 886.9 1760 2670 5150 Xylophone Hard Rubber Node 3 886.85 -

Wavedrum Voice Name List

Voice Name List Live mode Button Program Bank-a Programs 1 98 The Forest Drum 2 61 D&B Synth Head Rim Head Rim 3 15 Djembe (Double-size) No. Program No. Program Algo. Inst. Algo. Inst. Algo. Inst. Algo. Inst. 4 49 Steel Drum (F-A-B -C-F) Real Instrument 51 Balafon 7 51 25 81 Bank-b 0 Snare 1 (Double-size) 29 - - - 52 Gamelan 9 76 18 63 1 35 Tabla Drone 1 Snare 2 (Double-size) 30 - - - 53 EthnoOpera 7 61 15 72 2 75 Dance Hit Drone (Key of F) 2 Snare 3 (Double-size) 31 - - - 54 Koto Suite 20 79 20 66 3 0 Snare 1 (Double-size) 3 Velo Ambi Snare 19 17 2 12 55 Compton Kalling 20 5 22 15 4 50 Broken Kalimba 4 Multi Powerful Tom 5 22 24 21 56 Wind Bonga 7 8 19 28 Bank-c 5Krupa Abroad 2 267 10 57 Personality Split 7 10 16 78 1 59 Snare/Kick 2 (Double-size) 6 Pitched Toms w/Cowbell 19 24 4 22 Bass Drum/Snare Drum split 2 67 Kenya Street Rap 7 Ambi Taiko 9 23 19 12 58 Snare/Kick 1 (Double-size) 35 - - - 3 19 Conga (Double-size) 8 Viking War Machine 12 34 9 20 59 Snare/Kick 2 (Double-size) 36 - - - 4 82 DDL Mystic Jam 9 Vintage Electronic Toms 26 31 2 14 60 Kick The Synth 4 11 4 1 10 Okonkolo → Iya Dynamics 10 60 18 21 61 D&B Synth 4 16 23 85 11 Iya Boca/Slap Dynamics 10 58 14 29 62 Voice Perc.