Mount Hood El

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Play Fairway Analysis of the Central Cascades Arc-Backarc Regime, Oregon: Preliminary Indications

GRC Transactions, Vol. 39, 2015 Play Fairway Analysis of the Central Cascades Arc-Backarc Regime, Oregon: Preliminary Indications Philip E. Wannamaker1, Andrew J. Meigs2, B. Mack Kennedy3, Joseph N. Moore1, Eric L. Sonnenthal3, Virginie Maris1, and John D. Trimble2 1University of Utah/EGI, Salt Lake City UT 2Oregon State University, College of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, Corvallis OR 3Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Center for Isotope Geochemistry, Berkeley CA [email protected] Keywords Play Fairway Analysis, geothermal exploration, Cascades, andesitic volcanism, rift volcanism, magnetotellurics, LiDAR, geothermometry ABSTRACT We are assessing the geothermal potential including possible blind systems of the Central Cascades arc-backarc regime of central Oregon through a Play Fairway Analysis (PFA) of existing geoscientific data. A PFA working model is adopted where MT low resistivity upwellings suggesting geothermal fluids may coincide with dilatent geological structural settings and observed thermal fluids with deep high-temperature contributions. A challenge in the Central Cascades region is to make useful Play assessments in the face of sparse data coverage. Magnetotelluric (MT) data from the relatively dense EMSLAB transect combined with regional Earthscope stations have undergone 3D inversion using a new edge finite element formulation. Inversion shows that low resistivity upwellings are associated with known geothermal areas Breitenbush and Kahneeta Hot Springs in the Mount Jefferson area, as well as others with no surface manifestations. At Earthscope sampling scales, several low-resistivity lineaments in the deep crust project from the east to the Cascades, most prominently perhaps beneath Three Sisters. Structural geology analysis facilitated by growing LiDAR coverage is revealing numerous new faults confirming that seemingly regional NW-SE fault trends intersect N-S, Cascades graben- related faults in areas of known hot springs including Breitenbush. -

Land Areas of the National Forest System, As of September 30, 2019

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2019 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2019 Metric Equivalents When you know: Multiply by: To fnd: Inches (in) 2.54 Centimeters Feet (ft) 0.305 Meters Miles (mi) 1.609 Kilometers Acres (ac) 0.405 Hectares Square feet (ft2) 0.0929 Square meters Yards (yd) 0.914 Meters Square miles (mi2) 2.59 Square kilometers Pounds (lb) 0.454 Kilograms United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2019 As of September 30, 2019 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, DC 20250-0003 Website: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover Photo: Mt. Hood, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon Courtesy of: Susan Ruzicka USDA Forest Service WO Lands and Realty Management Statistics are current as of: 10/17/2019 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,994,068 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 503 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 149 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 456 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The Forest Service also administers several other types of nationally designated -

1922 Elizabeth T

co.rYRIG HT, 192' The Moootainetro !scot1oror,d The MOUNTAINEER VOLUME FIFTEEN Number One D EC E M BER 15, 1 9 2 2 ffiount Adams, ffiount St. Helens and the (!oat Rocks I ncoq)Ora,tecl 1913 Organized 190!i EDITORlAL ST AitF 1922 Elizabeth T. Kirk,vood, Eclttor Margaret W. Hazard, Associate Editor· Fairman B. L�e, Publication Manager Arthur L. Loveless Effie L. Chapman Subsc1·iption Price. $2.00 per year. Annual ·(onl�') Se,·ent�·-Five Cents. Published by The Mountaineers lncorJ,orated Seattle, Washington Enlerecl as second-class matter December 15, 19t0. at the Post Office . at . eattle, "\Yash., under the .-\0t of March 3. 1879. .... I MOUNT ADAMS lllobcl Furrs AND REFLEC'rION POOL .. <§rtttings from Aristibes (. Jhoutribes Author of "ll3ith the <6obs on lltount ®l!!mµus" �. • � J� �·,,. ., .. e,..:,L....._d.L.. F_,,,.... cL.. ��-_, _..__ f.. pt",- 1-� r�._ '-';a_ ..ll.-�· t'� 1- tt.. �ti.. ..._.._....L- -.L.--e-- a';. ��c..L. 41- �. C4v(, � � �·,,-- �JL.,�f w/U. J/,--«---fi:( -A- -tr·�� �, : 'JJ! -, Y .,..._, e� .,...,____,� � � t-..__., ,..._ -u..,·,- .,..,_, ;-:.. � --r J /-e,-i L,J i-.,( '"'; 1..........,.- e..r- ,';z__ /-t.-.--,r� ;.,-.,.....__ � � ..-...,.,-<. ,.,.f--· :tL. ��- ''F.....- ,',L � .,.__ � 'f- f-� --"- ��7 � �. � �;')'... f ><- -a.c__ c/ � r v-f'.fl,'7'71.. I /!,,-e..-,K-// ,l...,"4/YL... t:l,._ c.J.� J..,_-...A 'f ',y-r/� �- lL.. ��•-/IC,/ ,V l j I '/ ;· , CONTENTS i Page Greetings .......................................................................tlristicles }!}, Phoiitricles ........ r The Mount Adams, Mount St. Helens, and the Goat Rocks Outing .......................................... B1/.ith Page Bennett 9 1 Selected References from Preceding Mount Adams and Mount St. -

Sh Ood R Iver & W Asco C Ounties

2019-20 COLUMBIA GORGE S D AY & WEEKEND TRIPS- O REGON' S HOOD RIVER & WASCO COUNTIES TY HORSETAIL FALLS LOOP HIKE PANORAMA POINT VIENTO STATE PARK Along the scenic highway, adjacent to Oneonta Falls. Located South on Hwy 35 - It is part of Mt. Hood 541-374-8811 Also, take the 2.6-mile trail up to Pony Tail Falls. Loop Tour. I-84 west, Exit 56 • Hood River INDIAN CREEK GOLF COURSE See the area’s finest views of the Hood River Valley’s Trailheads and popular campgrounds in the forest. Hood River productive fruit industry, beautiful forests and VISTA HOUSE AT CROWN POINT 541-386-7770 majestic Mt Hood. Each season offers a different Corbett picture, from colorful spring blossoms through fall’s Friends of Vista House - year-round The 18-hole course features three meandering 503-695-2230 - rich colors and winter whites. Buses welcomed. 503-695-2240 - Gift Shop & Espresso Bar - creeks and views of Mt Hood and Mt Adams. THINGS TO DO PORT MARINA PARK spring thru fall KOBERG BEACH Mid-March thru October 9am-6pm daily t Hood River Off I-84 just east of Hood River 541-386-1645 November thru mid-March 10am-4pm Fri-Sun, weather e 1-800-551-6949 • 541-374-8811 • 503-695-2261 permitting Accessed westbound I-84 only. One of the windsurfers’ gathering spots in Hood River, No admission fee - donations gratefully accepted it’s the “Sailboarding Capital of the World.” Popular Scenic picnic and rest area. Built in 1917, Vista House is perched 733 feet LARCH MOUNTAIN windsurfing and viewing site, swimming beach, picnic above the Columbia Gorge and is also a visitor shelter, exercise course and jogging trail, and center featuring a 360-degree view of the river Travel 14 miles up Larch Mountain Rd from the scenic concessions. -

A Decision Framework for Managing the Spirit Lake and Toutle River System at Mount St

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://nap.edu/24874 SHARE A Decision Framework for Managing the Spirit Lake and Toutle River System at Mount St. Helens (2018) DETAILS 336 pages | 6 x 9 | PAPERBACK ISBN 978-0-309-46444-4 | DOI 10.17226/24874 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK Committee on Long-Term Management of the Spirit Lake/Toutle River System in Southwest Washington; Committee on Geological and Geotechnical Engineering; Board on Earth Sciences and Resources; Water Science and Technology Board; Division on Earth and Life Studies; Board on Environmental Change and Society; FIND RELATED TITLES Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine SUGGESTED CITATION National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2018. A Decision Framework for Managing the Spirit Lake and Toutle River System at Mount St. Helens. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24874. Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy -

Research Natural Areas on National Forest System Lands in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Utah, and Western Wyoming: a Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and Educators

USDA United States Department of Agriculture Research Natural Areas on Forest Service National Forest System Lands Rocky Mountain Research Station in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, General Technical Report RMRS-CTR-69 Utah, and Western Wyoming: February 2001 A Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and E'ducators Angela G. Evenden Melinda Moeur J. Stephen Shelly Shannon F. Kimball Charles A. Wellner Abstract Evenden, Angela G.; Moeur, Melinda; Shelly, J. Stephen; Kimball, Shannon F.; Wellner, Charles A. 2001. Research Natural Areas on National Forest System Lands in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Utah, and Western Wyoming: A Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and Educators. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-69. Ogden, UT: U.S. Departmentof Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 84 p. This guidebook is intended to familiarize land resource managers, scientists, educators, and others with Research Natural Areas (RNAs) managed by the USDA Forest Service in the Northern Rocky Mountains and lntermountain West. This guidebook facilitates broader recognitionand use of these valuable natural areas by describing the RNA network, past and current research and monitoring, management, and how to use RNAs. About The Authors Angela G. Evenden is biological inventory and monitoring project leader with the National Park Service -NorthernColorado Plateau Network in Moab, UT. She was formerly the Natural Areas Program Manager for the Rocky Mountain Research Station, Northern Region and lntermountain Region of the USDA Forest Service. Melinda Moeur is Research Forester with the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain ResearchStation in Moscow, ID, and one of four Research Natural Areas Coordinators from the Rocky Mountain Research Station. J. Stephen Shelly is Regional Botanist and Research Natural Areas Coordinator with the USDA Forest Service, Northern Region Headquarters Office in Missoula, MT. -

Red Hill Restoration Forest Service

United States Department of Agriculture Red Hill Restoration Forest Service Preliminary Assessment November 2012 Hood River Ranger District Mt. Hood National Forest Hood River County, Oregon Legal Description: T1S R8-9E; T2S, R8E; Willamette Meridian West Fork Hood River Watershed United States Department of Agriculture Red Hill Restoration Forest Service Preliminary Assessment November 2012 Hood River Ranger District Mt. Hood National Forest Hood River County, Oregon Legal Description: T1S R8-9E; T2S, R8E; Willamette Meridian Lead Agency: U.S. Forest Service Responsible Official: Chris Worth, Forest Supervisor Mt. Hood National Forest Information Contact: Jennie O'Connor Card Hood River Ranger District 6780 Highway 35 Mount Hood/Parkdale, OR 97041 (541) 352-6002 [email protected] Project Website: http://www.fs.fed.us/nepa/fs-usda- pop.php/?project=35969 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). -

Protecting Freshwater Resources on Mount Hood National Forest Recommendations for Policy Changes

PROTECTING FRESHWATER RESOURCES ON MOUNT HOOD NATIONAL FOREST RECOMMENDATIONS FOR POLICY CHANGES Produced by PACIFIC RIVERS COUNCIL Protecting Freshwater Resources on Mount Hood National Forest Pacific Rivers Council January 2013 Fisherman on the Salmon River Acknowledgements This report was produced by John Persell, in partnership with Bark and made possible by funding from The Bullitt Foundation and The Wilburforce Foundation. Pacific Rivers Council thanks the following for providing relevant data and literature, reviewing drafts of this paper, offering important discussions of issues, and otherwise supporting this project. Alex P. Brown, Bark Dale A. McCullough, Ph.D. Susan Jane Brown Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fisheries Commission Western Environmental Law Center G. Wayne Minshall, Ph.D. Lori Ann Burd, J.D. Professor Emeritus, Idaho State University Dennis Chaney, Friends of Mount Hood Lisa Moscinski, Gifford Pinchot Task Force Matthew Clark Thatch Moyle Patrick Davis Jonathan J. Rhodes, Planeto Azul Hydrology Rock Creek District Improvement Company Amelia Schlusser Richard Fitzgerald Pacific Rivers Council 2011 Legal Intern Pacific Rivers Council 2012 Legal Intern Olivia Schmidt, Bark Chris A. Frissell, Ph.D. Mary Scurlock, J.D. Doug Heiken, Oregon Wild Kimberly Swan Courtney Johnson, Crag Law Center Clackamas River Water Providers Clair Klock Steve Whitney, The Bullitt Foundation Klock Farm, Corbett, Oregon Thomas Wolf, Oregon Council Trout Unlimited Bronwen Wright, J.D. Pacific Rivers Council 317 SW Alder Street, Suite 900 Portland, OR 97204 503.228.3555 | 503.228.3556 fax [email protected] pacificrivers.org Protecting Freshwater Resources on Mt. Hood National Forest: 2 Recommendations for Policy Change Table of Contents Executive Summary iii Part One: Introduction—An Urban Forest 1 Part Two: Watersheds of Mt. -

3.2 Flood Level of Risk* to Flooding Is a Common Occurrence in Northwest Oregon

PUBLIC COMMENT DRAFT 11/07/2016 3.2 Flood Level of Risk* to Flooding is a common occurrence in Northwest Oregon. All Flood Hazards jurisdictions in the Planning Area have rivers with high flood risk called Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHA), except Wood High Village. Portions of the unincorporated area are particularly exposed to high flood risk from riverine flooding. •Unicorporated Multnomah County Developed areas in Gresham and Troutdale have moderate levels of risk to riverine flooding. Preliminary Flood Insurance Moderate Rate Maps (FIRMs) for the Sandy River developed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in 2016 •Gresham •Troutdale show significant additional risk to residents in Troutdale. Channel migration along the Sandy River poses risk to Low-Moderate hundreds of homes in Troutdale and unincorporated areas. •Fairview Some undeveloped areas of unincorporated Multnomah •Wood Village County are subject to urban flooding, but the impacts are low. Developed areas in the cities have a more moderate risk to Low urban flooding. •None Levee systems protect low-lying areas along the Columbia River, including thousands of residents and billions of dollars *Level of risk is based on the local OEM in assessed property. Though the probability of levee failure is Hazard Analysis scores determined by low, the impacts would be high for the Planning Area. each jurisdiction in the Planning Area. See Appendix C for more information Dam failure, though rare, can causing flooding in downstream on the methodology and scoring. communities in the Planning Area. Depending on the size of the dam, flooding can be localized or extreme and far-reaching. -

New Titles for Spring 2021 Green Trails Maps Spring

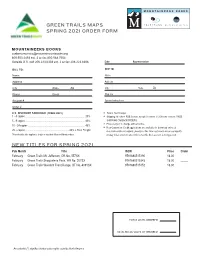

GREEN TRAILS MAPS SPRING 2021 ORDER FORM recreation • lifestyle • conservation MOUNTAINEERS BOOKS [email protected] 800.553.4453 ext. 2 or fax 800.568.7604 Outside U.S. call 206.223.6303 ext. 2 or fax 206.223.6306 Date: Representative: BILL TO: SHIP TO: Name Name Address Address City State Zip City State Zip Phone Email Ship Via Account # Special Instructions Order # U.S. DISCOUNT SCHEDULE (TRADE ONLY) ■ Terms: Net 30 days. 1 - 4 copies ........................................................................................ 20% ■ Shipping: All others FOB Seattle, except for orders of 25 books or more. FREE 5 - 9 copies ........................................................................................ 40% SHIPPING ON BACKORDERS. ■ Prices subject to change without notice. 10 - 24 copies .................................................................................... 45% ■ New Customers: Credit applications are available for download online at 25 + copies ................................................................45% + Free Freight mountaineersbooks.org/mtn_newstore.cfm. New customers are encouraged to This schedule also applies to single or assorted titles and library orders. prepay initial orders to speed delivery while their account is being set up. NEW TITLES FOR SPRING 2021 Pub Month Title ISBN Price Order February Green Trails Mt. Jefferson, OR No. 557SX 9781680515190 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Snoqualmie Pass, WA No. 207SX 9781680515343 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Wasatch Front Range, UT No. 4091SX 9781680515152 18.00 _____ TOTAL UNITS ORDERED TOTAL RETAIL VALUE OF ORDERED An asterisk (*) signifies limited sales rights outside North America. QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE WASHINGTON ____ 9781680513448 Alpine Lakes East Stuart Range, WA No. 208SX $18.00 ____ 9781680514537 Old Scab Mountain, WA No. 272 $8.00 ____ ____ 9781680513455 Alpine Lakes West Stevens Pass, WA No. -

Corridor Plan

HOOD RIVER MT HOOD (OR HIGHWAY 35) Corridor Plan Oregon Department of Transportation DOR An Element of the HOOD RIVER-MT. HOOD (OR 35) CORRIDOR PLAN Oregon Department of Transportahon Prepared by: ODOT Region I David Evans and Associates,Inc. Cogan Owens Cogan October 1997 21 October, 1997 STAFF REPORT INTERIM CORRIDOR STRATEGY HOOD RIVER-MT. HOOD (OR HWY 35) CORRIDOR PLAN (INCLUDING HWY 281 AND HWY 282) Proposed Action Endorsement of the Hood River-Mt. Hood (OR HWY 35) Corridor Strategy. The Qregon Bep ent of Transportation (ODOT) has been working wi& Tribal and local governments, transportation service providers, interest groups, statewide agencies and stakeholder committees, and the general public to develop a long-term plan for the Hood River-Mt. Hood (OR HWY 35) Corridor. The Hood River-Mt. Hood Corridor Plan is a long-range (20-year) program for managing all transportation modes within the Oregon Highway 35 corridor from the 1-84 junction to the US 26 junction (see Corridor Map). The first phase of that process has resulted in the attached Interim Com'dor Stvategy. The Interim Corridor Strategy is a critical element of the Hood River- Mt. Hood Corridor Plan. The Corridor Strategy will guide development of the Corridor Plan and Refinement Plans for specific areas and issues within the corridor. Simultaneous with preparation of the Corridor Plan, Transportation System Plans (TSPs) are being prepared for the cities of Hood River and Cascade Locks and for Hood River County. ODOT is contributing staff and financial resources to these efforts, both to ensure coordination between the TSPs and the Corridor Plan and to avoid duplication of efforts, e.g. -

Summit Ski Area Public Outreach and Stakeholder Engagement Report

APRIL 2019 SUMMIT SKI AREA DEVELOPMENT VISION PLANNING PROCESS PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT AND STAKEHOLDER OUTREACH REPORT AUTHORED BY: PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT AND STAKEHOLDER OUTREACH REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2. INTRODUCTION TO SUMMIT SKI AREA A. HISTORY AND BACKGROUND 3. PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT AND OUTREACH A. PURPOSE AND APPROACH 4. PARTICIPATING STAKEHOLDERS 5. STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT AND OUTREACH RESULTS A. KEY THEMES AND STAKEHOLDER RECOMMENDATIONS I. BEGINNER EXPERIENCE II. AFFORDABLE HOUSING III. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE IV. ENVIRONMENTAL STEWARDSHIP V. LOCAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT 6. CONCLUSION APRIL 2019 Public Engagement and StakeHolder OutreacH Report 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Summit Ski Area is tHe oldest ski area in tHe Pacific NortHwest and provides some of tHe most accessible beginner skiing and riding terrain in tHe region. In July 2018 tHe lease to operate Summit Ski Area was acquired by J.S.K. and Company, sister company to long-me operator of Timberline Lodge, R.L.K. and Company. STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT Company leadersHip Hired Sustainable NortHwest, a regional non-profit specializing in public engagement processes and public lands management, to organize and facilitate a series of stakeHolder mee_ngs. THe purpose of tHe stakeHolder mee_ngs was to gatHer input and ideas tHat may be integrated into tHe development vision for Summit Ski Area. Three stakeholder mee_ngs were held between MarcH 1 and March 7, 2019, and collec_vely brougHt togetHer 76 community leaders, businesses, environmental organiza_ons, and county, state, and federal agency partners. KEY THEMES There are five themes that emerged tHrougH tHe stakeHolder engagement meengs: 1. Beginner Experience 2. Affordable Housing 3. Transporta_on and Infrastructure 4.