Plasticity in Animated Children's Cartoons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

Animation:Then,Now,Next

Fall 2020 FYI, section 093 is a 2nd half of the semester course. If you wish to enroll in the full-semester version please email instructor FILM1600 : Then|Now|Next [email protected] for permission code. (August 17,2020) What you need to know! Designed to be online (asynchronous – anytime during the week) since 2016. It is not a zoom/IVC adaptation because of COVID. The course incorporates extensive visual media that make up the majority of the course content (no required book to purchase). It is now 99% Closed Captioned (spring 2020). Updated each semester with newest advances in the field. This course is 8 weeks long, which means things move a bit faster to fit everything in but is very manageable with good organization. What is different about this course… this is not a history course but reveals the people, processes and future changes in how animation is used in digital media. The content of the course draws directly from the professor’s experience and insights working at Disney Feature Animation and Electronic Arts (games). Weekly Modules are structured to emulate regular in-person classes. The modules contain each week's opening animations, lectures, readings, and quizzes. You can access the material several weeks before due dates. Course Content Animation techniques have evolved from simple cartoon drawings to 3D VFX. Today this evolution continues as it is Link to Sample Lecture Class rapidly being integrated into XR. From Animation's beginnings, (2 lectures per week) each new technological innovation extended the creative possibilities for storytelling (e.g. -

The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation Interactive Edition

The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation Interactive Edition By Michelle L. Walsh Submitted to the Faculty of the Information Technology Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in Information Technology University of Cincinnati College of Applied Science June 2006 The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation Interactive Edition by Michelle L. Walsh Submitted to the Faculty of the Information Technology Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in Information Technology © Copyright 2006 Michelle Walsh The author grants to the Information Technology Program permission to reproduce and distribute copies of this document in whole or in part. ___________________________________________________ __________________ Michelle L. Walsh Date ___________________________________________________ __________________ Sam Geonetta, Faculty Advisor Date ___________________________________________________ __________________ Patrick C. Kumpf, Ed.D. Interim Department Head Date Acknowledgements A great many people helped me with support and guidance over the course of this project. I would like to give special thanks to Sam Geonetta and Russ McMahon for working with me to complete this project via distance learning due to an unexpected job transfer at the beginning of my final year before completing my Bachelor’s degree. Additionally, the encouragement of my family, friends and coworkers was instrumental in keeping my motivation levels high. Specific thanks to my uncle, Keith -

Animating Race the Production and Ascription of Asian-Ness in the Animation of Avatar: the Last Airbender and the Legend of Korra

Animating Race The Production and Ascription of Asian-ness in the Animation of Avatar: The Last Airbender and The Legend of Korra Francis M. Agnoli Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Art, Media and American Studies April 2020 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. 2 Abstract How and by what means is race ascribed to an animated body? My thesis addresses this question by reconstructing the production narratives around the Nickelodeon television series Avatar: The Last Airbender (2005-08) and its sequel The Legend of Korra (2012-14). Through original and preexisting interviews, I determine how the ascription of race occurs at every stage of production. To do so, I triangulate theories related to race as a social construct, using a definition composed by sociologists Matthew Desmond and Mustafa Emirbayer; re-presentations of the body in animation, drawing upon art historian Nicholas Mirzoeff’s concept of the bodyscape; and the cinematic voice as described by film scholars Rick Altman, Mary Ann Doane, Michel Chion, and Gianluca Sergi. Even production processes not directly related to character design, animation, or performance contribute to the ascription of race. Therefore, this thesis also references writings on culture, such as those on cultural appropriation, cultural flow/traffic, and transculturation; fantasy, an impulse to break away from mimesis; and realist animation conventions, which relates to Paul Wells’ concept of hyper-realism. -

Perceptual Evaluation of Cartoon Physics: Accuracy, Attention, Appeal

Perceptual Evaluation of Cartoon Physics: Accuracy, Attention, Appeal Marcos Garcia∗ John Dingliana† Carol O’Sullivan‡ Graphics Vision and Visualisation Group, Trinity College Dublin Abstract deformations to real-time interactive physics simulations e.g. Cel Damage by Pseudo Interactive R and Electronic Arts R . A num- People have been using stylistic methods in classical animation for ber of papers have been published on simulating cartoon physics many years and such methods have also been recently applied in 3D using a range of different approaches from simple geometrical de- Computer Graphics. We have developed a method to apply squash formations to complex physically based models of elasticity. In this and stretch cartoon stylisations to physically based simulations in paper we present the results of a number of experiments that were real-time. In this paper, we present a perceptual evaluation of this performed to address the question of whether and to what degree approach in a series of experiments. Our hypotheses were: that styl- stylisation contributes to the quality of a real-time interactive simu- ised motion would improve user Accuracy (trajectory prediction); lation. that user Attention would be drawn more to objects with cartoon physics; and that animations with cartoon physics would have more 1.1 Contributions Appeal. In a task that required users to accurately predict the tra- jectories of bouncing objects with a range of elasticities and vary- Our main contribution in this paper is to validate some well known ing degrees of information, we found that stylisation significantly assumptions that stylised behaviour has the potential to signifi- improved user accuracy, especially for high elasticities and low in- cantly affect a user’s perception and response to a scene. -

Incongruous Surrealism Within Narrative Animated Film

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020- 2021 Incongruous Surrealism within Narrative Animated Film Daniel McCabe University of Central Florida Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd2020 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020- by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation McCabe, Daniel, "Incongruous Surrealism within Narrative Animated Film" (2021). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020-. 529. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd2020/529 INCONGRUOUS SURREALISM WITHIN NARRATIVE ANIMATED FILM by DANIEL MCCABE B.A. University of Central Florida, 2018 B.S.B.A. University of Central Florida, 2018 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Fine Arts in the School of Visual Arts and Design in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2021 © Daniel Francis McCabe 2021 ii ABSTRACT A pop music video is a form of media containing incongruous surrealistic imagery with a narrative structure supplied by song lyrics. The lyrics’ presence allows filmmakers to digress from sequential imagery through introduction of nonlinear visual elements. I will analyze these surrealist film elements through several post-modern philosophies to better understand how this animated audio-visual synthesis resides in the larger world of art theory and its relationship to the popular music video. -

Animation's Exclusion from Art History by Molly Mcgill BA, University Of

Hidden Mickey: Animation's Exclusion from Art History by Molly McGill B.A., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Art & Art History 2018 i This thesis entitled: Hidden Mickey: Animation's Exclusion from Art History written by Molly McGill has been approved for the Department of Art and Art History Date (Dr. Brianne Cohen) (Dr. Kirk Ambrose) (Dr. Denice Walker) The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the Department of Art History at the University of Colorado at Boulder for their continued support during the production of this master's thesis. I am truly grateful to be a part of a department that is open to non-traditional art historical exploration and appreciate everyone who offered up their support. A special thank you to my advisor Dr. Brianne Cohen for all her guidance and assistance with the production of this thesis. Your supervision has been indispensable, and I will be forever grateful for the way you jumped onto this project and showed your support. Further, I would like to thank Dr. Kirk Ambrose and Dr. Denice Walker for their presence on my committee and their valuable input. I would also like to extend my gratitude to Catherine Cartwright and Jean Goldstein for listening to all my stress and acting as my second moms while I am so far away from my own family. -

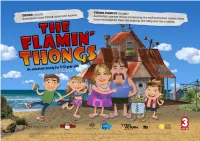

An Animated Comedy for 8-12 Year Olds 26 X 12Min SERIES

An animated comedy for 8-12 year olds 26 x 12min SERIES © 2014 MWP-RDB Thongs Pty Ltd, Media World Holdings Pty Ltd, Red Dog Bites Pty Ltd, Screen Australia, Film Victoria and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Whale Bay isis homehome toto thethe disaster-pronedisaster-prone ThongThong familyfamily andand toto Australia’sAustralia’s leastleast visitedvisited touristtourist attraction,attraction, thethe GiantGiant Thong.Thong. ButBut thatthat maymay bebe about to change, for all the wrong reasons... Series Synopsis ........................................................................3 Holden Character Guide....................................................4 Narelle Character Guide .................................................5 Trevor Character Guide....................................................6 Brenda Character Guide ..................................................7 Rerp/Kevin/Weedy Guide.................................................8 Voice Cast.................................................................................9 ...because it’s also home to Holden Thong, a 12-year-old with a wild imagination Creators ...................................................................................12 and ability to construct amazing gadgets from recycled scrap. Holden’s father Director’s‘ Statement..........................................................13 Trevor is determined to put Whale Bay on the map, any map. Trevor’s hare-brained tourist-attracting schemes, combined with Holden’s ill-conceived contraptions, -

Contentious Comedy

1 Contentious Comedy: Negotiating Issues of Form, Content, and Representation in American Sitcoms of the Post-Network Era Thesis by Lisa E. Williamson Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Glasgow Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies 2008 (Submitted May 2008) © Lisa E. Williamson 2008 2 Abstract Contentious Comedy: Negotiating Issues of Form, Content, and Representation in American Sitcoms of the Post-Network Era This thesis explores the way in which the institutional changes that have occurred within the post-network era of American television have impacted on the situation comedy in terms of form, content, and representation. This thesis argues that as one of television’s most durable genres, the sitcom must be understood as a dynamic form that develops over time in response to changing social, cultural, and institutional circumstances. By providing detailed case studies of the sitcom output of competing broadcast, pay-cable, and niche networks, this research provides an examination of the form that takes into account both the historical context in which it is situated as well as the processes and practices that are unique to television. In addition to drawing on existing academic theory, the primary sources utilised within this thesis include journalistic articles, interviews, and critical reviews, as well as supplementary materials such as DVD commentaries and programme websites. This is presented in conjunction with a comprehensive analysis of the textual features of a number of individual programmes. By providing an examination of the various production and scheduling strategies that have been implemented within the post-network era, this research considers how differentiation has become key within the multichannel marketplace. -

EFFECTIVE DIRECTED GAZE for CHARACTER ANIMATION By

EFFECTIVE DIRECTED GAZE FOR CHARACTER ANIMATION by Tomislav Pejsa A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Computer Sciences) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN–MADISON 2016 Date of final oral examination: 9/12/16 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Michael L. Gleicher, Professor, Computer Sciences Bilge Mutlu, Associate Professor, Computer Sciences Eftychios Sifakis, Assistant Professor, Computer Sciences Kevin Ponto, Assistant Professor, Design Studies Hrvoje Benko, Senior Researcher, Microsoft Research c Copyright by Tomislav Pejsa 2016 All Rights Reserved i This dissertation is dedicated to my Mom. ii acknowledgments In the Fall of 2010, I was a doctoral student in Croatia and my research career was floundering. The dismal financial situation in my country had left me without funding and, although I was halfway resigned to a future of writing enterprise code, I decided to take one last gamble. I wrote an email to Mike Gleicher—whose work had profoundly shaped my research interests—asking if I could work for him as a visiting scholar. Mike introduced me to Bilge, and the two of them invited me to join a project that would eventually become the third chapter of this dissertation. I eagerly accepted their offer and a few short months later I was boarding a plane to the United States. What was initially envisioned as a brief scholarly visit soon turned into an epic, six-year adventure in the frozen plains of Wisconsin. We accomplished much during that time, yet none of it would have been been possible had my advisors not taken a gamble of their own that Fall. -

Animating Experiences of Girlhood in Bob's Burgers Katie

I’m (Not) A Girl: Animating Experiences of Girlhood in Bob’s Burgers Item Type Article Authors Barnett, Katie Citation Barnett, K. (2019). "I’m (Not) A Girl: Animating Experiences of Girlhood in Bob’s Burgers." Journal of Popular Television, 7(1), 3-23. DOI 10.1386/jptv.7.1.3_1 Publisher Intellect Journal Journal of Popular Television Download date 27/09/2021 00:37:22 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/621344 I’m (Not) A Girl: Animating Experiences of Girlhood in Bob’s Burgers Katie Barnett, University of Chester Abstract Discourses of girlhood increasingly acknowledge its mutability, with the ‘girl’ as a complex image that cannot adequately be conceptualized by age or biology alone. Likewise, theories of animation often foreground its disruptive potential. Taking an interdisciplinary approach that encompasses girlhood studies, animation studies, and screen studies, this article analyses the representation of the two main girl characters, Tina and Louise Belcher, in the animated sitcom Bob’s Burgers (2011–present). Taking this concept of mutability as its central focus, it argues that animation is an ideal medium for representing girlhood, given its disruptive potential and non-linear capacities, whereby characters are often frozen in time. With no commitment to aging its young female characters, Bob’s Burgers is instead able to construct a landscape of girlhood that allows for endless reversal, contradiction and overlap in the experiences of Tina and Louise, whose existence as animations reveals girlhood as a liminal space in which girls can be one thing and the other – gullible and intelligent, vulnerable and strong, sexual and innocent – without negating their multifarious experiences. -

Cartoon Animation Free

FREE CARTOON ANIMATION PDF Preston Blair | 224 pages | 25 Oct 1996 | Walter Foster Publishing | 9781560100843 | English | Laguna Hills, CA, United States ToonyPhotos - Turn Photos into Cartoons Animation is a method in which figures are manipulated to appear as moving images. In traditional animation Cartoon Animation, images are drawn or painted by hand on transparent celluloid sheets to Cartoon Animation photographed and exhibited on film. Today, most animations are made with computer-generated imagery CGI. Computer animation can be very detailed 3D animationwhile 2D computer animation can be used for stylistic reasons, low bandwidth or faster real-time renderings. Other common animation methods apply a stop motion technique to two and three-dimensional objects like paper cutoutspuppets or clay figures. Commonly the effect of animation is achieved by a rapid succession of sequential images that minimally Cartoon Animation from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon and beta movementbut the exact causes are still uncertain. Television and video are popular electronic animation media that originally were analog and now operate digitally. For display on the computer, techniques like animated GIF and Flash animation were developed. Animation is more pervasive than many people realize. Apart from short filmsfeature Cartoon Animationtelevision series, animated GIFs and other media dedicated to the display of moving images, animation is also prevalent in video gamesmotion graphicsuser interfaces and visual effects. The physical movement of image parts through simple mechanics—in for instance moving images in magic lantern shows—can also be considered animation. The mechanical manipulation of three-dimensional puppets and objects to emulate living beings has a very long history in automata.