Tay Landscape Partnership Scheme Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERTHSHIRE POST OFFICES (Updated 22/2/2020)

PERTHSHIRE POST OFFICES (updated 22/2/2020) Aberargie 17-1-1855: BRIDGE OF EARN. 1890 ABERNETHY RSO. Rubber 1899. 7-3-1923 PERTH. Closed 29-11-1969. Aberdalgie 16-8-1859: PERTH. Rubber 1904. Closed 11-4-1959. ABERFELDY 1788: POST TOWN. M.O.6-12-1838. No.2 allocated 1844. 1-4-1857 DUNKELD. S.B.17-2-1862. 1865 HO / POST TOWN. T.O.1870(AHS). HO>SSO 1-4-1918 >SPSO by 1990 >PO Local 31-7-2014. Aberfoyle 1834: PP. DOUNE. By 1847 STIRLING. M.O.1-1-1858: discont.1-1-1861. MO-SB 1-8-1879. No.575 issued 1889. By 4/1893 RSO. T.O.19-11-1895(AYL). 1-8-1905 SO / POST TOWN. 19-1-1921 STIRLING. Abernethy 1837: NEWBURGH,Fife. MO-SB 1-4-1875. No.434 issued 1883. 1883 S.O. T.O.2-1-1883(AHT) 1-4-1885 RSO. No.588 issued 1890. 1-8-1905 SO / POST TOWN. 7-3-1923 PERTH. Closed 30-9-2008 >Mobile. Abernyte 1854: INCHTURE. 1-4-1857 PERTH. 1861 INCHTURE. Closed 12-8-1866. Aberuthven 8-12-1851: AUCHTERARDER. Rubber 1894. T.O.1-9-1933(AAO)(discont.7-8-1943). S.B.9-9-1936. Closed by 1999. Acharn 9-3-1896: ABERFELDY. Rubber 1896. Closed by 1999. Aldclune 11-9-1883: BLAIR ATHOL. By 1892 PITLOCHRY. 1-6-1901 KILLIECRANKIE RSO. Rubber 1904. Closed 10-11-1906 (‘Auldclune’ in some PO Guides). Almondbank 8-5-1844: PERTH. Closed 19-12-1862. Re-estd.6-12-1871. MO-SB 1-5-1877. -

The Post Office Perth Directory

i y^ ^'^•\Hl,(a m \Wi\ GOLD AND SILVER SMITH, 31 SIIG-S: STI^EET. PERTH. SILVER TEA AND COFFEE SERVICES, BEST SHEFFIELD AND BIRMINGHAM (!^lettro-P:a3tteto piateb Crutt mb spirit /tamtjs, ^EEAD BASKETS, WAITEKS, ^NS, FORKS, FISH CARVERS, ci &c. &c. &c. ^cotct) pearl, pebble, arib (STatntgorm leroeller^. HAIR BRACELETS, RINGS, BROOCHES, CHAINS, &c. PLAITED AND MOUNTED. OLD PLATED GOODS RE-FINISHED, EQUAL TO NEW. Silver Plate, Jewellery, and Watches Repaired. (Late A. Cheistie & Son), 23 ia:zc3-i3: sti^eet^ PERTH, MANUFACTURER OF HOSIERY Of all descriptions, in Cotton, Worsted, Lambs' Wool, Merino, and Silk, or made to Order. LADIES' AND GENTLEMEN'S ^ilk, Cotton, anb SEoollen ^\}xxi^ attb ^Mktt^, LADIES' AND GENTLEMEN'S DRAWERS, In Silk, Cotton, Worsted, Merino, and Lambs' Wool, either Kibbed or Plain. Of either Silk, Cotton, or Woollen, with Plain or Ribbed Bodies] ALSO, BELTS AND KNEE-CAPS. TARTAN HOSE OF EVERY VARIETY, Or made to Order. GLOVES AND MITTS, In Silk, Cotton, or Thread, in great Variety and Colour. FLANNEL SHOOTING JACKETS. ® €^9 CONFECTIONER AND e « 41, GEORGE STREET, COOKS FOR ALL KINDS OP ALSO ON HAND, ALL KINDS OF CAKES AND FANCY BISCUIT, j^jsru ICES PTO*a0^ ^^te mmU to ©vto- GINGER BEER, LEMONADE, AND SODA WATER. '*»- : THE POST-OFFICE PERTH DIRECTOEI FOR WITH A COPIOUS APPENDIX, CONTAINING A COMPLETE POST-OFFICE DIRECTORY, AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. COMPILED AND ARRANGED BY JAMES MAESHALL, POST-OFFICE. WITH ^ pUtt of tl)e OTtts atiti d^nmxonn, ENGEAVED EXPRESSLY FOB THE WORK. PEETH PRINTED FOR THE PUBLISHER BY C. G. SIDEY, POST-OFFICE. -

A Guide to Perth and Kinross Councillors

A Guide to Perth and Kinross Councillors Who’s Who Guide 2017-2022 Key to Phone Numbers: (C) - Council • (M) - Mobile Alasdair Bailey Lewis Simpson Labour Liberal Democrat Provost Ward 1 Ward 2 Carse of Gowrie Strathmore Dennis Melloy Conservative Tel 01738 475013 (C) • 07557 813291 (M) Tel 01738 475093 (C) • 07909 884516 (M) Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Ward 2 Strathmore Angus Forbes Colin Stewart Conservative Conservative Ward 1 Ward 2 Carse of Gowrie Strathmore Tel 01738 475034 (C) • 07786 674776 (M) Email [email protected] Tel 01738 475087 (C) • 07557 811341 (M) Tel 01738 475064 (C) • 07557 811337 (M) Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Provost Depute Beth Pover Bob Brawn Kathleen Baird SNP Conservative Conservative Ward 1 Ward 3 Carse of Gowrie Blairgowrie & Ward 9 Glens Almond & Earn Tel 01738 475036 (C) • 07557 813405 (M) Tel 01738 475088 (C) • 07557 815541 (M) Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Fiona Sarwar Tom McEwan Tel 01738 475086 (C) • 07584 206839 (M) SNP SNP Email [email protected] Ward 2 Ward 3 Strathmore Blairgowrie & Leader of the Council Glens Tel 01738 475020 (C) • 07557 815543 (M) Tel 01738 475041 (C) • 07984 620264 (M) Murray Lyle Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Conservative Caroline Shiers Ward 7 Conservative Strathallan Ward 3 Ward Map Blairgowrie & Glens Tel 01738 475037 (C) • 07557 814916 (M) Tel 01738 475094 (C) • 01738 553990 (W) Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Ward 11 Perth City North Ward 12 Ward 4 Perth City Highland -

Perth & Kinross Council Archive

Perth & Kinross Council Archive Collections Business and Industry MS5 PD Malloch, Perth, 1883-1937 Accounting records, including cash books, balance sheets and invoices,1897- 1937; records concerning fishings, managed or owned by PD Malloch in Perthshire, including agreements, plans, 1902-1930; items relating to the maintenance and management of the estate of Bertha, 1902-1912; letters to PD Malloch relating to various aspects of business including the Perthshire Fishing Club, 1883-1910; business correspondence, 1902-1930 MS6 David Gorrie & Son, boilermakers and coppersmiths, Perth, 1894-1955 Catalogues, instruction manuals and advertising material for David Gorrie and other related firms, 1903-1954; correspondence, specifications, estimates and related materials concerning work carried out by the firm, 1893-1954; accounting vouchers, 1914-1952; photographic prints and glass plate negatives showing machinery and plant made by David Gorrie & Son including some interiors of laundries, late 19th to mid 20th century; plans and engineering drawings relating to equipment to be installed by the firm, 1892- 1928 MS7 William and William Wilson, merchants, Perth and Methven, 1754-1785 Bills, accounts, letters, agreements and other legal papers concerning the affairs of William Wilson, senior and William Wilson, junior MS8 Perth Theatre, 1900-1990 Records of Perth Theatre before the ownership of Marjorie Dence, includes scrapbooks and a few posters and programmes. Records from 1935 onwards include administrative and production records including -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

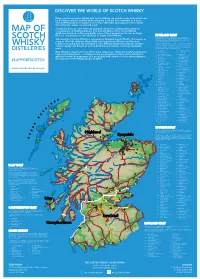

2019 Scotch Whisky

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

DALLRAOICH Strathtay • Pitlochry • Perthshire DALLRAOICH Strathtay • Pitlochry Perthshire • PH9 0PJ

DALLRAOICH Strathtay • Pitlochry • PerthShire DALLRAOICH Strathtay • Pitlochry PerthShire • Ph9 0PJ A handsome victorian house in the sought after village of Strathtay Aberfeldy 7 miles, Pitlochry 10 miles, Perth 27 miles, Edinburgh 71 miles, Glasgow 84 miles (all distances are approximate) = Open plan dining kitchen, 4 reception rooms, cloakroom/wc 4 Bedrooms (2 en suite), family bathroom Garage/workshop, studio, garden stores EPC = E About 0.58 Acres Savills Perth Earn House Broxden Business Park Lamberkine Drive Perth PH1 1RA [email protected] Tel: 01738 445588 SITUATION Dallraoich is situated on the western edge of the picturesque village of Strathtay in highland Perthshire. The village has an idyllic position on the banks of the River Tay and is characterised by its traditional stone houses. Strathtay has a friendly community with a village shop and post office at its heart. A bridge over the Tay links Strathtay to Grandtully where there is now a choice of places to eat out. Aberfeldy is the nearest main centre and has all essential services, including a medical centre. The town has a great selection of independent shops, cafés and restaurants, not to mention the Birks cinema which as well as screening mainstream films has a popular bar and café and hosts a variety of community activities. Breadalbane Academy provides nursery to sixth year secondary education. Dallraoich could hardly be better placed for enjoying the outdoors. In addition to a 9 hole golf course at Strathtay, there are golf courses at Aberfeldy, Kenmore, Taymouth Castle, Dunkeld and Pitlochry. Various water sports take place on nearby lochs and rivers, with the rapids at Grandtully being popular for canoeing and rafting. -

Plot 1B Seasyde, Errol, Perthshire, PH2 7TA

Let’s get a move on! Plot 1B Seasyde, Errol, Perthshire, PH2 7TA www.thorntons-property.co.uk Offers Over £175,000 Final opportunity to purchase a superb 2.3 acre site overlooking • 2.3 Acre site The Tay • Final remaining plot Last remaining plot at Seasyde occupies a prime position in a rural location in proximity to an A-listed Georgian country house on the banks of the Firth • Idyllic setting of Tay, which is a site of significant scientific interest due to its spectacular • Views over the Tay bird life. The plots are in an idyllic setting within the picturesque Carse of Gowrie 3 miles from the village of Errol. • Situated down a mile long The impressive plot, extending to approximately 2.3 acres, is situated down private road a mile long private road, surrounded by farm land, with superb views south • Surrounded by farm land over the Tay, reed beds, bird sanctuary and goose roost, and would be suitable for an extensive single property. • Extensive garden This plot takes full advantage of open views across the Firth of Tay, south • Services near facing from the north shore, and affords the opportunity to design an extensive garden in an ideal setting. Services are close to hand. Potential • Errol Village and amenities buyers should consider these advantages in assessing this development 3 miles away which gives the opportunity to design and build a house which would complement the surrounding properties, subject to obtaining the necessary Planning Permission. Seasyde is dominated by Seasyde House, and Lodge being the A listed childhood home of Admiral Duncan, Scotland’s greatest sailor and victor of Camperdown. -

A Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols Traci N

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2016 Gender Reflections: a Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols Traci N. Billings University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, European History Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Billings, Traci N., "Gender Reflections: a Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1351. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1351 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENDER REFLECTIONS: A RECONSIDERATION OF PICTISH MIRROR AND COMB SYMBOLS by Traci N. Billings A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Anthropology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2016 ABSTRACT GENDER REFLECTIONS: A RECONSIDERATION OF PICTISH MIRROR AND COMB SYMBOLS by Traci N. Billings The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2016 Under the Supervision of Professor Bettina Arnold, PhD. The interpretation of prehistoric iconography is complicated by the tendency to project contemporary male/female gender dichotomies into the past. Pictish monumental stone sculpture in Scotland has been studied over the last 100 years. Traditionally, mirror and comb symbols found on some stones produced in Scotland between AD 400 and AD 900 have been interpreted as being associated exclusively with women and/or the female gender. This thesis re-examines this assumption in light of more recent work to offer a new interpretation of Pictish mirror and comb symbols and to suggest a larger context for their possible meaning. -

Laurel Cottage, 25 Druids Park, Murthly PH1 4EH Guide Price

Laurel Cottage, 25 Druids Park, Murthly PH1 4EH Guide Price £149,000 Home Report Valuation £155,000 Mc Cash & Hunter Solicitors & Estate Agents This beautifully-appointed detached harled an equally nice outlook currently used as a Cottage enjoys a peaceful cul-de-sac location second bedroom with an illuminated recess on a generous corner plot of approximately with cupboards beneath, however could also a third of an acre in the highly sought after make an ideal dining room. The bright dual- residential Druids Park area of Murthly, some aspect kitchen is fitted with a range of white 12 miles from Perth. This thriving village wall and base units with contrasting work enjoys countryside views and woodland walks tops and includes a ceramic hob with electric and a variety of local amenities which include oven, larder fridge and freezer, automatic a newly opened bistro pub, primary school, washing machine, and glazed door leading to general store with post office, Stewart Tower the log store and rear garden. The generous Dairy café and farm shop and Bankfoot Visitors main bedroom has a peaceful outlook, ample Centre, close by. There is a regular ‘bus service space for furniture and an illuminated recess to the surrounding areas and the A9, just a with wash-hand basin with vanity units short drive away gives access to Perth and its beneath. From the hall an archway leads to further shops, business and leisure facilities the bathroom which is fitted with a coloured and provides easy commuting to all major suite including a bath with electric shower cities and airports in the central belt, and and mirrored vanity units. -

Leslie's Directory for Perth and Perthshire

»!'* <I> f^? fI? ffi tfe tI» rl? <Iy g> ^I> tf> <& €l3 tf? <I> fp <fa y^* <Ti* ti> <I^ tt> <& <I> tf» *fe jl^a ^ ^^ <^ <ft ^ <^ ^^^ 9* *S PERTHSHIRE COLLECTION including KINROSS-SHIRE These books form part of a local collection permanently available in the Perthshire Room. They are not available for home reading. In some cases extra copies are available in the lending stock of the Perth and Kinross District Libraries. fic^<fac|3g|jci»^cpcia<pci><pgp<I>gpcpcx»q»€pcg<I»4>^^ cf>' 3 ^8 6 8 2 5 TAMES M'NICOLL, BOOT AND SHOE MAKER, 10 ST. JOHN STREET, TID "XT' "IIP rri "tur .ADIES' GOODS IN SILK, SATIN, KID, AND MOROCCO. lENT.'S HUNTING, SHOOTING, WALKING, I DRESS, IN KID AND PATENT. Of the Newest and most Fashionable Makes, £ THE SCOTTISH WIDOWS' FUNDS AND REVENUE. The Accumulated Funds exceed £9,200,000 The Annual Revenue exceeds 1,100,000 The Largest Funds and Revenue possessed by any Life Assurance Institution in the United Kingdom. THE PROFITS are ascertained Septennially and divided among the Members in Bonus Addi- tions to their Policies, computed in the corrfpoundioxva.^ i.e., on Original Sums Assured and previous Bonus Additions attaching to the Policy—an inter- mediate Bonus being also added to Claims between Divisions ; thus, practically an ANNUAL DIVISION OF PROFITS is made among the Policyholders, founded on the ample basis of seven years' operations, yielding to each his equitable share down to date of death, in respect of every Premium paid since the date of the policy. -

The Excavation of Two Later Iron Age Fortified Homesteads at Aldclune

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 127 (1997), 407-466 excavatioe Th lateo tw r f Ironfortifieo e nAg d homesteads at Aldclune, Blair Atholl, Perth & Kinross R Hingley*, H L Mooref, J E TriscottJ & G Wilsonf with contribution AshmoreJ P y sb , HEM Cool DixonD , , LehaneD MateD I , McCormickF , McCullaghJ P R , McSweenK , y &RM Spearman ABSTRACT Two small 'forts', probably large round houses, occupying naturala eminence furtherand defended by banks and ditches at Aldclune, by Blair Atholl (NGR: NN 894 642), were excavated in advance of road building. Construction began Siteat between2 second firstthe and centuries Siteat 1 BC and between the second and third centuries AD. Two major phases of occupation were found at each site. The excavation was funded by the former SDD/Historic Buildings and Monuments Directorate with subsequent post-excavation and publication work funded by Historic Scotland. INTRODUCTION In 1978 the Scottish Development Department (Ancient Monuments) instigated arrangements for excavation whe becamt ni e known tha plannee tth d re-routin trun9 A e k th roa likels f go dwa y to destroy two small 'forts' at Aldclune, by Blair Atholl (NGR: NN 894 642). A preliminary programm f triao e l trenching bega n Aprii n l 1980, revealing that substantial e areath f o s structure d theian s r defences survived e fac n th vieI . t f wo tha t both sites wer f higo e h archaeological potentia would an l almose db t completely obliterate roae th dy dbuildingb s wa t ,i decide proceeo dt d with full-scale excavation.