Sri Lanka: Visit of the UN Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epidemiology Unit

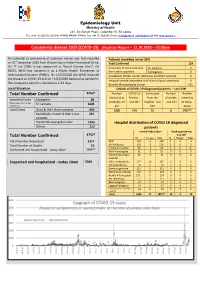

Epidemiology Unit Ministry of Health 231, De Saram Place, Colombo 10, Sri Lanka Tele: (+94 11) 2695112, 2681548, 4740490, 4740491, 4740492 Fax: (+94 11) 2696583 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Web: www.epid.gov.lk Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) - Situation Report – 12.10.2020 – 10.00am An outbreak of pneumonia of unknown reason was first reported Patients identified in last 24H st on 31 December 2019 from Wuhan City in Hubei Province of China. Total Confirmed 124 th On 7 Jan 2020, it was diagnosed as “Novel Corona Virus”. On Returnees (+ close contacts) Sri Lankans 3 30/01, WHO has declared it as a Public Health Emergency of from other countries Foreigners 0 International Concern (PHEIC). On 11/02/2020 the WHO renamed Kandakadu Rehab. Center detainees and their contacts 0 the disease as COVID-19 and on 11/03/2020 declared as pandemic. Hospital samples (admitted with clinical signs/symptoms) 0 The incubation period is reported as 2-14 days. Brandix Minuwangoda cluster 121 Local Situation Details of COVID 19 diagnosed patients – Last 24H 4752* Number COVID 19 Discharged Number Number Total Number Confirmed inward as at Positive - from the of deaths inward as Imported Cases Foreigners 86 yesterday-10 last 24H hospital - last - last 24H at today- (Returnees from other Sri Lankans 1446 countries) am 24H 10 am Local Cases Navy & their close contacts 950 1308 124 10 0 1422** Kandakadu cluster & their close 651 contacts Brandix Minuwangoda cluster 1306 Hospital distribution of COVID 19 diagnosed Others 313 patients Inward Today -

Ruwanwella) Mrs

Lady Members First State Council (1931 - 1935) Mrs. Adline Molamure by-election (Ruwanwella) Mrs. Naysum Saravanamuttu by-election (Colombo North) (Mrs. Molamure was the first woman to be elected to the Legislature) Second State Council (1936 - 1947) Mrs. Naysum Saravanamuttu (Colombo North) First Parliament (House of Representatives) (1947 - 1952) Mrs. Florence Senanayake (Kiriella) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena by-election (Avissawella) Mrs. Tamara Kumari Illangaratne by-election (Kandy) Second Parliament (House of (1952 - 1956) Representatives) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena (Avissawella) Mrs. Doreen Wickremasinghe (Akuressa) Third Parliament (House of Representatives) (1956 - 1959) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene (Colombo North) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena (Kiriella) Mrs. Vimala Wijewardene (Mirigama) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna by-election (Welimada) Lady Members Fourth Parliament (House of (March - April 1960) Representatives) Mrs. Wimala Kannangara (Galigomuwa) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Soma Wickremanayake (Dehiowita) Fifth Parliament (House of Representatives) (July 1960 - 1964) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Soma Wickremanayake (Dehiowita) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene by-election (Borella) Sixth Parliament (House of Representatives) (1965 - 1970) Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Mrs. Sivagamie Obeyesekere (Mirigama) Mrs. Wimala Kannangara (Galigomuwa) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Leticia Rajapakse by-election (Dodangaslanda) Mrs. Mallika Ratwatte by-election (Balangoda) Seventh Parliament (House of (1970 - 1972) / (1972 - 1977) Representatives) & First National State Assembly Mrs. Kusala Abhayavardhana (Borella) Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene (Dehiwala - Mt.Lavinia) Lady Members Mrs. Tamara Kumari Ilangaratne (Galagedera) Mrs. Sivagamie Obeyesekere (Mirigama) Mrs. Mallika Ratwatte (Balangoda) Second National State Assembly & First (1977 - 1978) / (1978 - 1989) Parliament of the D.S.R. of Sri Lanka Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Miss. -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

Towards a Zero Waste Solution for Sri Lanka

TOWARDS A ZERO WASTE SOLUTION FOR SRI LANKA Jayaratne Kananke Arachchilage, President, Sevanatha Urban Resource Centre Introduction to Matale and Ratnapura Matale Municipality . Population: 48,500 . Land area: 8.6 sq.km . City Status: District Capital . Location:108 km from the capital city, Colombo . Total Waste Generation: 21 – 23 t. p/d . Daily Collection by the MC: 17 – 18 t. Disposal Method: Open Dumping Ratnapura Municipality . Population: 58,500 (2013) . Land area: 22.18 sq.km . City Status: District Capital famous for Gem Mining and Processing . Location:140 km from the capital city . Total Waste Generation: 28-30 t. p/d . Daily Waste Collection by the MC: 23 – 25 t. Disposal Method: Open Dumping Sevanatha Overview of Project Activities In both Matale and Ratnapura • Partnerships between ESCAP, Sevanatha and the municipal council have been established for the implementation of the project • Land for the IRRC has been allocated by the municipal council • ESCAP and the Central Environment Authority have paid for construction • Operation by Micro Enriched Compost (MEC), a social entreprise established by Sevanatha • Under the partnership, community awareness raising and information campaigns have been regular and supported by Sevanatha • The Central Government has been kept closely informed of progress Sevanatha Performance of IRRCs in both Cities in 2014 Matale Ratnapura Organic waste - Tons 1408 869 Recyclables - Tons 42 13 Compost - Tons 49 9 Income - UDS 8,200 1,131 Emission Reduction 552 322 tCO2 Both cities have accepted IRRC -

Sri Lanka Dambulla • Sigiriya • Matale • Kandy • Bentota • Galle • Colombo

SRI LANKA DAMBULLA • SIGIRIYA • MATALE • KANDY • BENTOTA • GALLE • COLOMBO 8 Days - Pre-Designed Journey 2018 Prices Travel Experience by private car with guide Starts: Colombo Ends: Colombo Inclusions: Highlights: Prices Per Person, Double Occupancy: • All transfers and sightseeing excursions by • Climb the Sigiriya Rock Fortress, called the private car and driver “8th wonder of the world” • Your own private expert local guides • Explore Minneriya National Park, dedicated $2,495.00 • Accommodations as shown to preserving Sri Lanka’s wildlife • Meals as indicated in the itinerary • Enjoy a spice tour in Matale • Witness a Cultural Dance Show in Kandy • Tour the colonial Dutch architecture in Galle & Colombo • See the famous Gangarama Buddhist Temple DAY 1 Colombo / Negombo, SRI LANKA Jetwing Beach On arrival in Colombo, you are transferred to your resort hotel in the relaxing coast town of Negombo. DAYS 2 & 3 • Meals: B Dambulla / Sigiriya Heritage Kandalama Discover the Dambulla Caves Rock Temple, dating back to the 1st century BC. In Sigiriya, climb the famed historic 5th century Sigiriya Rock Fortress, called the “8th wonder of the world”. Visit the age-old city of Polonnaruwa, and the Minneriya National Park - A wildlife sanctuary, the park is dry season feeding ground for the regional elephant population. DAY 4 • Meals: B Matale / Kandy Cinnamon Citadel Stop in Matale to enjoy an aromatic garden tour and taste its world-famous spices such as vanilla and cinnamon. Stay in the Hill Country capital of Kandy, the last stronghold of Sinhala kings and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Explore the city’s holy Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic, Gem Museum, Kandy Bazaar, and the Royal Botanical Gardens. -

Update UNHCR/CDR Background Paper on Sri Lanka

NATIONS UNIES UNITED NATIONS HAUT COMMISSARIAT HIGH COMMISSIONER POUR LES REFUGIES FOR REFUGEES BACKGROUND PAPER ON REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS FROM Sri Lanka UNHCR CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH GENEVA, JUNE 2001 THIS INFORMATION PAPER WAS PREPARED IN THE COUNTRY RESEARCH AND ANALYSIS UNIT OF UNHCR’S CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH ON THE BASIS OF PUBLICLY AVAILABLE INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND COMMENT, IN COLLABORATION WITH THE UNHCR STATISTICAL UNIT. ALL SOURCES ARE CITED. THIS PAPER IS NOT, AND DOES NOT, PURPORT TO BE, FULLY EXHAUSTIVE WITH REGARD TO CONDITIONS IN THE COUNTRY SURVEYED, OR CONCLUSIVE AS TO THE MERITS OF ANY PARTICULAR CLAIM TO REFUGEE STATUS OR ASYLUM. ISSN 1020-8410 Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS.............................................................................................................................. 3 1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... 4 2 MAJOR POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS IN SRI LANKA SINCE MARCH 1999................ 7 3 LEGAL CONTEXT...................................................................................................................... 17 3.1 International Legal Context ................................................................................................. 17 3.2 National Legal Context........................................................................................................ 19 4 REVIEW OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION............................................................... -

Sri Lanka Page 1 of 7

Sri Lanka Page 1 of 7 Sri Lanka International Religious Freedom Report 2008 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor The Constitution accords Buddhism the "foremost place" and commits the Government to protecting it, but does not recognize it as the state religion. The Constitution also provides for the right of members of other religious groups to freely practice their religious beliefs. There was no change in the status of respect for religious freedom by the Government during the period covered by this report. While the Government publicly endorses religious freedom, in practice, there were problems in some areas. There were sporadic attacks on Christian churches by Buddhist extremists and some societal tension due to ongoing allegations of forced conversions. There were also attacks on Muslims in the Eastern Province by progovernment Tamil militias; these appear to be due to ethnic and political tensions rather than the Muslim community's religious beliefs. The U.S. Government discusses religious freedom with the Government as part of its overall policy to promote human rights. U.S. Embassy officials conveyed U.S. Government concerns about church attacks to government leaders and urged them to arrest and prosecute the perpetrators. U.S. Embassy officials also expressed concern to the Government about the negative impact anticonversion laws could have on religious freedom. The U.S. Government continued to discuss general religious freedom concerns with religious leaders. Section I. Religious Demography The country has an area of 25,322 square miles and a population of 20.1 million. Approximately 70 percent of the population is Buddhist, 15 percent Hindu, 8 percent Christian, and 7 percent Muslim. -

Sri Lanka Red Cross Society

Humanitarian Operations Presented by : Sudath Madugalle Deputy Director General/ Head of Operations Sri Lanka Red Cross Society VISION MISSION PRINCIPLES Reduce risk, build capacity and Safer, resilient and socially inclusive Humanity | Impartiality | promote principles and values by communities through improving Neutrality Independence | Voluntary mobilizing resources, creating lifestyles and changing mind-sets. service Unity and Universality universal access to services through volunteerism and partnership Contact Us SRI LANKA RED CROSS SOCIETY 104, Dharmapala Mawatha, Colombo 07, Sri Lanka | +94 11 2691095 | [email protected] 2 Sri Lanka Red Cross Society Flood and Landslide Operation 2017 Sri Lanka Red Cross Society serves its constituents through flood and landslide relief and recovery – May 2017 Contact Us SRI LANKA RED CROSS SOCIETY 104, Dharmapala Mawatha, Colombo 07, Sri Lanka | +94 11 2691096 | [email protected] 5 Source: Daily News – 24th June 2017 Contact Us SRI LANKA RED CROSS SOCIETY 104, Dharmapala Mawatha, Colombo 07, Sri Lanka | +94 11 2691096 | [email protected] 4 SLRCS was in direct contact with DM authorities at national level, continuously. It also published alerts regularly on its website. Contact Us SRI LANKA RED CROSS SOCIETY 104, Dharmapala Mawatha, Colombo 07, Sri Lanka | +94 11 2691096 | [email protected] 3 Map of Sri Lanka Showing the the most severely affected districts Contact Us SRI LANKA RED CROSS SOCIETY 104, Dharmapala Mawatha, Colombo 07, Sri Lanka | +94 11 2691096 | [email protected] 6 SLRCS RESPONSE 1st Phase - Emergency 1. Search and Rescue Operations Galle, Matara, Kalutara, Gampaha and Ratnapura Districts Contact Us SRI LANKA RED CROSS SOCIETY 104, Dharmapala Mawatha, Colombo 07, Sri Lanka | +94 11 2691096 | [email protected] 7 2. -

MATALE DISTRICT Administrative Map

MATALE DISTRICT Administrative map Name & P-code of DS Divisions Map Locator Ambanganga Koralaya 2221 Dambulla 2206 Galewela 2203 Laggala-Pallegama 2224 Matale 2218 Naula 2209 Pallepola 2212 Rattota 2230 Ukuwela 2233 Wilgamuwa 2227 Yatawatta 2215 Diganpathaha ! Sigiriya ! Polattawa ANURADHAPURA Etorahena ! ! ! Inamalawa Alakolawewa ! Pallegama! Lenewa ! Pelwehera ! ! Mirisgoni Oya Junction DAMBULLA POLONNARUWA Legend Ratmalagaha ela Makulgaswewa ! Gonawela ! ! DS Division Boundary ! Tittawelgolla Talakiriyagama ! Ridiella ! Main Road ! Beliyakanda Kalundewa ! Railway Line GALEWELA Pannampitiya ! ! Siyambalagaswewa Bambaragahawatta Galewela ! ! ! Lenadora District HQ ! Walakumbura ! Pubbiliya ! ! Town Wahakotte ! Waralanda ! ! Dewaradapola ! Hewanewela Medapihilla ! ! ! Pilihudugolla Madipola Elagomuwa ! Yodagannawa NAULA ! ! Kandepitawela ! Nalanda ! Millawana Kathurupitiya ! Ambana ! Akuramboda ! Kaluganga Kambarawa ! PALLEPOLA ! ! Dunuwila Kohalanwela Galboda ! ! Madawala Akaranadiya ! Dammanatenna Paldeniya ! ! ! Weliwaranagolla KURUNEGALA ! Radunnewela Data Source: Talakolawela ! Mahawela ! ! Karagahatenna ! Galgedawala Gammaduwa ! Survey Department, MATALE ! LAGGALA-PALLEGAMA Yatawatta Madumana Government of Sri Lanka ! AMBANGANGA ! ! Pubbarawela WILGAMUWA Dombawala KORALAYA ! Airports: Air Broker Center 1998 Guruwela Oggomuwa YATAWATTA Dankanda ! ! ! ! Meda-Ela ! Palapatwela ! Pallegama Rattota Etanwela !Kapuruwediwela ! ! Aluvihare! Production Date: 06 Sep, 2005 ! Ranamure Kaikawala ! Kiulewadiya ! ! Matale Weragama ! !! Narangomuwa -

Spatial Variability of Rainfall Trends in Sri Lanka from 1989 to 2019 As an Indication of Climate Change

International Journal of Geo-Information Article Spatial Variability of Rainfall Trends in Sri Lanka from 1989 to 2019 as an Indication of Climate Change Niranga Alahacoon 1,2,* and Mahesh Edirisinghe 1 1 Department of Physics, University of Colombo, Colombo 00300, Sri Lanka; [email protected] 2 International Water Management Institute (IWMI), 127, Sunil Mawatha, Pelawatte, Colombo 10120, Sri Lanka * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Analysis of long-term rainfall trends provides a wealth of information on effective crop planning and water resource management, and a better understanding of climate variability over time. This study reveals the spatial variability of rainfall trends in Sri Lanka from 1989 to 2019 as an indication of climate change. The exclusivity of the study is the use of rainfall data that provide spatial variability instead of the traditional location-based approach. Henceforth, daily rainfall data available at Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation corrected with stations (CHIRPS) data were used for this study. The geographic information system (GIS) is used to perform spatial data analysis on both vector and raster data. Sen’s slope estimator and the Mann–Kendall (M–K) test are used to investigate the trends in annual and seasonal rainfall throughout all districts and climatic zones of Sri Lanka. The most important thing reflected in this study is that there has been a significant increase in annual rainfall from 1989 to 2019 in all climatic zones (wet, dry, intermediate, and Semi-arid) of Sri Lanka. The maximum increase is recorded in the wet zone and the minimum increase is in the semi-arid zone. -

Weather and Climate Outlook

Weather and Climate Outlook Pre South-West Monsoon 29 April 2020 Seasonal outlook for impacts of the South- West Monsoon and response plans within the context of COVID-19. Highlights • The South West-Monsoon is expected to establish over Sri Lanka during mid to late May 2020. Colombo, Kalutara, Gampaha, Galle, Matara, Ratnapura and Kegalle districts are at very high risk of the monsoon impact. • In general, a normal rainfall outlook for South Asia from June to September is predicted, considering all phenomenal climatological parameters. • The southern territories of South Asia including Sri Lanka may however receive slightly above-normal rainfall during the four-month season. Single extreme events in Sri Lanka are possible, especially at the onset of the monsoon, as revealed at the Monsoon Forum held on 29 April. Pre-monsoon predictions • The above-normal temperature observed in all parts of • Cyclonic activity is foreseen from 1 to 6 May, moving the country during the past two months may continue till towards the north-east of the Bay of Bengal towards early May. Myanmar. • Based on the most likely scenario, an estimated 35,000 to • Rain and wind conditions may slightly increase over the 50,000 families may be affected in 3 to 4 Districts at the south-west of Sri Lanka during 30 April to 4 May however, onset of the monsoon, based on analysis of historical no major impact is predicted for Sri Lanka. floods and landslides. • Special guidelines at central and district level have been issued for response and relief management, planning for early evacuations and camp management under health regulations etc, in the context of COVID-19. -

SRI LANKA: CIVILIAN Information Bulletin No

SRI LANKA: CIVILIAN Information Bulletin no. 03/2006 DISPLACEMENT 01 September 2006 The Federation’s mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organization and its mil lions of volunteers are active in 185 countries. In Brief This Bulletin is being issued for information only, and reflects the situation and the information available at this time. The Federation is not seeking funding or other assistance from donors for this operation at this time. Clashes between the Sri Lankan armed forces and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), in north and east Sri Lanka, have led to the displacement of more than 207,000 civilians fleeing their homes in the affected areas. The majority of internally displaced persons are from areas in Jaffna, Trincomalee and Batticaloa, where fighting has intensified since the end of July 2006. The Federation and its partnering national societies are working together with the Sri Lanka Red Cross Society (SLRCS) and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to conduct humanitarian relief efforts across the affected areas. For further information specifically related to this operation please contact: · In Sri Lanka: Sri Lanka Red Cross Society, Mr. Susil Perera (Executive Director, Disaster Management), phone: +94 77 3600971 · In Sri Lanka: Sri Lanka Delegation, Mr. Al Panico (Head of Delegation), email: [email protected], phone: +94 11 4528698, fax: +94 11 2682671 · In India: South Asia Regional Delegation, Ms. Nina Nobel (Acting Head of Regional Delegation), email: [email protected], phone: +91.11.2411.1125, fax: +91.11.2411.1128 · In Geneva: Asia Pacific Department, Ms.