Confronted by HEIDI J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 27, 2018 RESTORATION of CAPPONI CHAPEL in CHURCH of SANTA FELICITA in FLORENCE, ITALY, COMPLETED THANKS to SUPPORT FROM

Media Contact: For additional information, Libby Mark or Heather Meltzer at Bow Bridge Communications, LLC, New York City; +1 347-460-5566; [email protected]. March 27, 2018 RESTORATION OF CAPPONI CHAPEL IN CHURCH OF SANTA FELICITA IN FLORENCE, ITALY, COMPLETED THANKS TO SUPPORT FROM FRIENDS OF FLORENCE Yearlong project celebrated with the reopening of the Renaissance architectural masterpiece on March 28, 2018: press conference 10:30 am and public event 6:00 pm Washington, DC....Friends of Florence celebrates the completion of a comprehensive restoration of the Capponi Chapel in the 16th-century church Santa Felicita on March 28, 2018. The restoration project, initiated in March 2017, included all the artworks and decorative elements in the Chapel, including Jacopo Pontormo's majestic altarpiece, a large-scale painting depicting the Deposition from the Cross (1525‒28). Enabled by a major donation to Friends of Florence from Kathe and John Dyson of New York, the project was approved by the Soprintendenza Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio di Firenze, Pistoia, e Prato, entrusted to the restorer Daniele Rossi, and monitored by Daniele Rapino, the Pontormo’s Deposition after restoration. Soprintendenza officer responsible for the Santo Spirito neighborhood. The Capponi Chapel was designed by Filippo Brunelleschi for the Barbadori family around 1422. Lodovico di Gino Capponi, a nobleman and wealthy banker, purchased the chapel in 1525 to serve as his family’s mausoleum. In 1526, Capponi commissioned Capponi Chapel, Church of St. Felicita Pontormo to decorate it. Pontormo is considered one of the most before restoration. innovative and original figures of the first half of the 16th century and the Chapel one of his greatest masterpieces. -

THE ICONOGRAPHY of MEXICAN FOLK RETABLOS by Gloria Kay

The iconography of Mexican folk retablos Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Giffords, Gloria Fraser, 1938- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 03/10/2021 20:27:37 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/552047 THE ICONOGRAPHY OF MEXICAN FOLK RETABLOS by Gloria Kay Fraser Giffords A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ART In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN HISTORY OF ART In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 9 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manu script in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: Robert M. -

Politics of the Blessed Lady: Catholic Art in the Contemporary Hungarian Culture Industry

religions Article Politics of the Blessed Lady: Catholic Art in the Contemporary Hungarian Culture Industry Marc Roscoe Loustau McFarland Center for Religion, Culture and Ethics, College of the Holy Cross, Worcester, MA 02131, USA; [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +1-857-222-6955 Abstract: I examine Hungary’s Catholic arts industry and its material practices of cultural production: the institutions and professional disciplines through which devotional material objects move as they become embedded in political processes of national construction and contestation. Ethnographic data come from thirty-six months of fieldwork in Hungary and Transylvania, and focuses on three museum and gallery exhibitions of Catholic devotional objects. Building on critiques of subjectivity- and embodiment-focused research, I highlight how the institutional legacies of state socialism in Hungary and Romania inform a national politics of Catholic materiality. Hungarian cultural institutions and intellectuals have been drawn to work with Catholic art because Catholic material culture sustains a meaningful presence across multiple scales of political contestation at the local, regional, and state levels. The movement of Catholic ritual objects into the zone of high art and cultural preservation necessitates that these objects be mobilized for use within the political agendas of state-embedded institutions. Yet, this mobilization is not total. Ironies, confusions, and contradictions continue to show up in Transylvanian Hungarians’ historical memory, destabilizing these political uses. Keywords: Catholicism; nationalism; art; Virgin Mary; Hungary; Romania Citation: Loustau, Marc Roscoe. 2021. Politics of the Blessed Lady: Catholic Art in the Contemporary 1. Introduction Hungarian Culture Industry. Religions The growing body of historical and anthropological literature on Catholic devotional 12: 577. -

Christopher White Table of Contents

Christopher White Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Peter the “rock”? ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Churches change over time ...................................................................................................................... 6 The Church and her earthly pilgrimage .................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1 The Apostle Peter (d. 64?) : First Bishop and Pope of Rome? .................................................. 11 Peter in Rome ......................................................................................................................................... 12 Yes and No .............................................................................................................................................. 13 The death of Peter .................................................................................................................................. 15 Chapter 2 Pope Sylvester (314-335): Constantine’s Pope ......................................................................... 16 Constantine and his imprint .................................................................................................................... 17 “Remembering” Sylvester ...................................................................................................................... -

110 Culture 110 Cu Ltu Re

images of orphans in fine art By Rita ANOKHIN, Yuriy KUDINOV “ONE PICTURE IS WORTH A THOUSAND WORDS,” a popular saying rphaned characters are extremely common as literary protagonists, and abandonment by par- ents is a persistent theme in myth, fairy tales, fantasy, ancient poetry, and children’s literature. We À nd orphaned heroes in sacred texts: Moses, the great prophet was abandoned in infancy; and in legends, such as that of the founding of Rome by Romulus and Remus who were reared by a she-wolf. OThe classic orphan is one of the most widespread characters in literature. For example: in the 19th century one can À nd Dickens’ Oliver Twist and David CopperÀ eld; Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn; and Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre. In the 20th century we meet James Henry Trotter from Roald Dahl’s James and the Giant Peach; Dorothy from the Wizard of Oz; and the Harry Potter series, À rst published in 1997. So far, young Mr. Potter has been arguably the most famous character – orphaned or otherwise – of the 21st century. Authors orphan their characters in order to free them from family obligations and supervision, to force them to pursue a more interesting or adventurous life, or simply to deprive them of a more prosaic exist- ence. The removal of parents and loving guardians creates self-contained, introspective characters who strive for affection. Although orphans can be a useful literary technique, these invented lives do not reÁ ect reality. Orphaned characters in À ction are often remarkably – even unbelievably – successful, sentimental, or wise beyond their years. -

Lipa 1 the Reaction to the Last Judgment Joseph Lipa History Of

Lipa 1 The Reaction to the Last Judgment Joseph Lipa History of Art 351 Professor Willette April 29, 2013 Lipa 2 From the moment of its unveiling on All Hallow’s Eve in 1541 to its near demolition in the decades to follow, Michelangelo’s famed Last Judgment evoked a reaction only surpassed in variety by the human figure it depicted. Commissioned six years before by Pope Paul III, this colossal fresco of the resurrection of the body at the end of the world spanned the altar wall of the same Sistine Chapel whose ceiling Michelangelo had painted some twenty years earlier. Whether stunned by its intricacy, sobered by its content, or even scandalized by its apparent indecency, sixteenth-century minds could not stop discussing what was undoubtedly both the most famous and the most controversial work of its day. “This work is the true splendor of all Italy and of artists, who come from the Hyperborean ends of the earth to see and draw it,” exclaimed Italian Painter Gian Paolo Lomazzo, nonetheless one of the fresco’s fiercest critics.”1 To be sure, neither Lomazzo nor any of Michelangelo’s contemporaries doubted his artistic skill. On the contrary, it was precisely Michelangelo’s unparalleled ability to depict the nude human body that caused the work to be as severely criticized by some as it was highly praised by others. While critics and acclaimers alike often varied in their motives, the polarizing response to the Last Judgment can only be adequately understood in light of the unique religious circumstances of its time. -

Art Guide 2015 Columban Art Calendar Front Cover

2015 Columban Art Calendar Art Guide 2015 Columban Art Calendar Front Cover Virgin and Child (detail) by Domenico Ghirlandaio (c.1470-1475) Amongst the subjects favoured by Renaissance masters and their patrons, that of the Virgin and Child must rank as the most beloved. The archetypal image of a serene young woman embracing her child has never failed to appeal to viewers searching for reassurance or mercy. With consummate skill Ghirlandaio evokes the physical presence of the young mother, whose heavy folds of blue fabric create a protective space to enclose her son. The gold background reminiscent of heaven reminds us of the Virgin’s ancient title as “God- Bearer,” the one who made possible the Incarnation. The rock crystal mounted at the centre of the fabulous jewel had traditionally symbolized purity. Thus the magnificent object, known as a morse, which served to fasten the priest’s robe at the neck, here decorates the Virgin’s neckline. As a symbol of purity, the rock crystal alludes to a quality that both poets and theologians had long ascribed to Christ’s mother. Ghirlandaio’s artistry elevates this rather familiar image into a symbol of Mary’s archetypal role as protector and mediator. January 2015 St Paul and the Viper (detail) Mural, Canterbury Cathedral by English School (c. 1180) St Paul is remembered as a great missionary, who after his conversion preached throughout Asia Minor and as far west as Rome and Malta. This wall painting, which once decorated Canterbury Cathedral, recalls an incident recounted in Acts 28:1-6. Paul had been arrested and was on his way to Rome, where he was to be tried. -

Open Access Version Via Utrecht University Repository

Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka 3930424 March 2018 Master Thesis Art History of the Low Countries in its European Context University of Utrecht Prof. dr. M.A. Weststeijn Prof. dr. E. Manikowska 1 Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Index Introduction p. 4 Historiography and research motivation p. 4 Theoretical framework p. 12 Research question p. 15 Chapters summary and methodology p. 15 1. The collection of Stanisław August 1.1. Introduction p. 18 1.1.1. Catalogues p. 19 1.1.2. Residences p. 22 1.2. Netherlandish painting in the collection in general p. 26 1.2.1. General remarks p. 26 1.2.2. Genres p. 28 1.2.3. Netherlandish painting in the collection per stylistic schools p. 30 1.2.3.1. The circle of Rubens and Van Dyck p. 30 1.2.3.2. The circle of Rembrandt p. 33 1.2.3.3. Italianate landscapists p. 41 1.2.3.4. Fijnschilders p. 44 1.2.3.5. Other Netherlandish artists p. 47 1.3. Other painting schools in the collection p. 52 1.3.1. Paintings by court painters in Warsaw p. 52 1.3.2. Italian paintings p. 53 1.3.3. French paintings p. 54 1.3.4. German paintings p. -

Popes, Bishops, Deacons, and Priests: Church Leadership in the Middle Ages

Popes, Bishops, Deacons, and Priests: Church Leadership in the Middle Ages by Colin D. Smith Popes, Bishops, Deacons, and Priests: Church Leadership in the Middle Ages 2 Introduction In January of 1077, at the apparent climax of what became known as the Investiture Controversy, Henry IV, the stubborn German Emperor, stood barefoot in a hair shirt in the snow outside the castle of Canossa, Italy, begging the pope, Gregory VII for clemency. During the course of the quarrel, Henry had attempted to depose the pope, and the pope responded by excommunicating the emperor and those bishops that sided with him. Historians seem to agree that Henry’s repentance was not all it seemed, and he was actually trying to win back his people and weaken the pope’s hand. In a sense, however, the motive behind why Henry did what he did is less important than the fact that, by the eleventh century, the church had come to figure so prominently, and the pope had ascended to such a position of both secular and ecclesiastical influence. That such a conflict between emperor and pope existed and had to be dealt with personally by the emperor himself bears testimony to the power that had come to reside with the Bishop of Rome. The purpose of this paper is to survey the growth of the church offices, in particular the papacy, from their biblical foundations, through to the end of the Middle Ages. In the process, the paper will pay attention to the development of traditions, the deviations from Biblical command and practice, and those who recognized the deviations and sought to do something about them. -

Design and Renovation Guidelines and Protocols

GUIDELINES and PROTOCOLS for the DESIGN and RENOVATION of CHURCHES and CHAPELS First Sunday of Advent December 1, 2013 Catholic Diocese of Saginaw Office of Liturgy The Office of Liturgy for the Diocese of Saginaw has prepared this set of guidelines and protocols to be used in conjunction with those outlined in Built of Living Stones. This diocesan document attempts to give clearer direction to those areas that Built of Living Stones leaves open to particular diocesan recommendations and directives. All those involved in any design for new construction or renovation project of a church or chapel in the Diocese of Saginaw should be familiar with these guidelines and protocols and ensure that their intent is incorporated into any proposed design. Guidelines and Protocols for the Design And Renovation of Churches and Chapels Text 2009, Diocese of Saginaw, Office of Liturgy. Latest Revision Date: December 1, 2013. Excerpts from Built of Living Stones: Art, Architecture, and Worship: Guidelines of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops copyright 2001, United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Washington, DC. Used with permission. All rights reserved. Excerpts taken with permission and appreciation from similar publications from the following: Archdiocese of Chicago; Diocese of Grand Rapids; Diocese of Seattle; Archdiocese of Milwaukee; Diocese of Lexington; Archdiocese of Philadelphia and Diocese of La Crosse. No part of these works may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the copyright holder. Printed in the United States of America For you have made the whole world a temple of your glory, that your name might everywhere be extolled, yet you allow us to consecrate to you apt places for the divine mysteries. -

The Perfect Way by Anna Bonus Kingsford and Edward Maitland the Perfect Way Or the Finding of Christ

The Perfect Way by Anna Bonus Kingsford and Edward Maitland The Perfect Way or The Finding of Christ by Anna Bonus Kingsford and Edward Maitland Published in 1888 Boston, Mass.: ESOTERIC PUBLISHING COMPANY, 478 Shawmut Avenue. (Revised and Enlarged Edition.) Page 1 The Perfect Way by Anna Bonus Kingsford and Edward Maitland AUTHORS’ EXPLANATION These lectures were delivered in London, before a private audience, in the months of May, June, and July, 1881. The changes made in this edition calling for indication, are, – the substitution of another Lecture for No. V., and consequent omission of most of the plates; the rewriting, in the whole or part, of paragraphs 6 - 8 and 28 in No. I.; 34 - 36 in No. II.; 5 - 8, 12, 13, 22, 23, 42, 43, 54, and 55, in No. IX. (the latter paragraphs being replaced by a new one); the lengthening of Appendices II, and VI; the addition of a new Part to Appendix XIII. (formerly No. IX); and the substitution of eight new Appendices for Nos:. VII., and VIII. The alterations involve no change or withdrawal of doctrine, but only extension of scope, amplification of statement, or modification of expression. A certain amount of repetition being inseparable from the form adopted, – that of a series of expository lectures, each requiring to be complete in itself, – and the retention of that form being unavoidable, – no attempt has been made to deal with the instances in which repetition occurs. PREFACE TO THE AMERICAN EDITION In presenting an American edition of THE PERFECT WAY, or, The Finding of Christ, to the reading and inquiring public, we have been actuated by the conviction that a comprehensive textbook of the “new views,” or the restored wisdom and knowledge of the ages regarding religion or the perfect life, was imperatively required, wherein the subject was treated in a manner luminous, instructive, and entertaining, and which, without abridgement, or inferiority of material or workmanship, could yet be sold at a price that would bring the work within the means of the general public. -

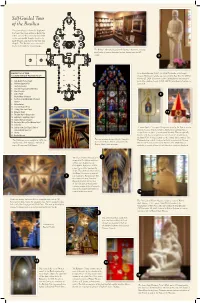

Self-Guided Tour of the Basilica 13

Self-Guided Tour of the Basilica 13 This tour takes you from the baptismal 14 font near the main entrance, down the 12 center aisle to the sanctuary, then right to the east apsidal chapels, back to the 16 15 11 Lady Chapel, and then to the west side chapels. The Basilica museum may be 18 17 7 10 reached through the west transept. 9 The Bishops’ Museum, located in the Basilica’s basement, contains pontificalia of various American bishops, dating from the 19th century. 11 6 5 20 19 8 4 3 BASILICA OF THE Saint André Bessette, C.S.C. (1845-1937), founder of St. Joseph’s SACRED HEART FLOOR PLAN Oratory, Montréal, Canada, was canonized by Pope Benedict XVI on October 17, 2010. The statue of Saint André Bessette was designed 1. Font, Ambry, Paschal Candle by the Rev. Anthony Lauck, C.S.C. (1985). Saint André’s feast day is 2. Holtkamp Organ (1978) 8 January 6. 3. Sanctuary Crossing 2 4. Seal of the Congregation of Holy Cross 1 5. Altar of Sacrifice 6. Ambo (Pulpit) 9 7. Original Altar / Tabernacle 8. East Transept and World War I Memorial Entrance 9. Tintinnabulum 10. St. Joseph Chapel (Pietà) 11. St. Mary / Bro. André Chapel 2 12. Reliquary Chapel 17 13. The Lady Chapel / Baroque Altar 14. Holy Angels / Guadalupe Chapel 15. Mural of Our Lady of Lourdes 16. Our Lady of Victory / Basil Moreau Chapel 17. Ombrellino 18. Stations of the Cross Chapel / Tomb of A “minor basilica” is a special designation given by the Pope to certain John Cardinal O’Hara, C.S.C.