An Introduction to the Astrolabe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Science LR 2711

A Scientific Response to the Chester Beatty Library Collection Contents The Roots Of Modern Science A Scientific Response To The Chester Beatty Library Collection 1 Science And Technology 2 1 China 3 Science In Antiquity 4 Golden Age Of Islamic Science 5 Transmission Of Knowledge To Europe 6 A Scientific Response To The Chester Beatty Library Collections For Dublin City Of Science 2012 7 East Asian Collections The Great Encyclopaedia of the Yongle Reign (Yongle Dadian) 8 2 Phenomena of the Sky (Tianyuan yuli xiangyi tushuo) 9 Treatise on Astronomy and Chronology (Tianyuan lili daquan) 10 Illustrated Scrolls of Gold Mining on Sado Island (Sado kinzan zukan) 11 Islamic Collections Islamic Medicine 12 3 Medical Compendium, by al-Razi (Al-tibb al-mansuri) 13 Encyclopaedia of Medicine, by Ibn Sina (Al-qanun fi’l-tibb) 14 Treatise on Surgery, by al-Zahrawi (Al-tasrif li-man ‘ajiza ‘an al-ta’lif) 15 Treatise on Human Anatomy, by Mansur ibn Ilyas (Tashrih al-badan) 16 Barber –Surgeon toolkit from 1860 17 Islamic Astronomy and Mathematics 18 The Everlasting Cycles of Lights, by Muhyi al-Din al-Maghribi (Adwar al-anwar mada al-duhur wa-l-akwar) 19 Commentary on the Tadhkira of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi 20 Astrolabes 21 Islamic Technology 22 Abbasid Caliph, Ma’mum at the Hammam 23 European Collections European Science of the Middle Ages 24 4 European Technology: On Military Matters (De Re Militari) 25 European Technology: Concerning Military Matters (De Re Militari) 26 Mining Technology: On the Nature of Metals (De Re Metallica) 27 Fireworks: The triumphal -

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere A Constellation of Rare Books from the History of Science Collection The exhibition was made possible by generous support from Mr. & Mrs. James B. Hebenstreit and Mrs. Lathrop M. Gates. CATALOG OF THE EXHIBITION Linda Hall Library Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering and Technology Cynthia J. Rogers, Curator 5109 Cherry Street Kansas City MO 64110 1 Thinking Outside the Sphere is held in copyright by the Linda Hall Library, 2010, and any reproduction of text or images requires permission. The Linda Hall Library is an independently funded library devoted to science, engineering and technology which is used extensively by The exhibition opened at the Linda Hall Library April 22 and closed companies, academic institutions and individuals throughout the world. September 18, 2010. The Library was established by the wills of Herbert and Linda Hall and opened in 1946. It is located on a 14 acre arboretum in Kansas City, Missouri, the site of the former home of Herbert and Linda Hall. Sources of images on preliminary pages: Page 1, cover left: Peter Apian. Cosmographia, 1550. We invite you to visit the Library or our website at www.lindahlll.org. Page 1, right: Camille Flammarion. L'atmosphère météorologie populaire, 1888. Page 3, Table of contents: Leonhard Euler. Theoria motuum planetarum et cometarum, 1744. 2 Table of Contents Introduction Section1 The Ancient Universe Section2 The Enduring Earth-Centered System Section3 The Sun Takes -

The Persian-Toledan Astronomical Connection and the European Renaissance

Academia Europaea 19th Annual Conference in cooperation with: Sociedad Estatal de Conmemoraciones Culturales, Ministerio de Cultura (Spain) “The Dialogue of Three Cultures and our European Heritage” (Toledo Crucible of the Culture and the Dawn of the Renaissance) 2 - 5 September 2007, Toledo, Spain Chair, Organizing Committee: Prof. Manuel G. Velarde The Persian-Toledan Astronomical Connection and the European Renaissance M. Heydari-Malayeri Paris Observatory Summary This paper aims at presenting a brief overview of astronomical exchanges between the Eastern and Western parts of the Islamic world from the 8th to 14th century. These cultural interactions were in fact vaster involving Persian, Indian, Greek, and Chinese traditions. I will particularly focus on some interesting relations between the Persian astronomical heritage and the Andalusian (Spanish) achievements in that period. After a brief introduction dealing mainly with a couple of terminological remarks, I will present a glimpse of the historical context in which Muslim science developed. In Section 3, the origins of Muslim astronomy will be briefly examined. Section 4 will be concerned with Khwârizmi, the Persian astronomer/mathematician who wrote the first major astronomical work in the Muslim world. His influence on later Andalusian astronomy will be looked into in Section 5. Andalusian astronomy flourished in the 11th century, as will be studied in Section 6. Among its major achievements were the Toledan Tables and the Alfonsine Tables, which will be presented in Section 7. The Tables had a major position in European astronomy until the advent of Copernicus in the 16th century. Since Ptolemy’s models were not satisfactory, Muslim astronomers tried to improve them, as we will see in Section 8. -

Claudius Ptolemy: Astronomy and Cosmography Johann Stöffler And

Issue 12 I 2012 MUSEUM of the BROADSHEET communicates the work of the HISTORY Museum of the History of Science, Oxford. of Available at www.mhs.ox.ac.uk, sold in the SCIENCE museum shop, and distributed to members Books, Globes and Instruments in the Exhibition of the Museum. 1. Claudius Ptolemy, Almagest (Venice, 1515) 2. Johann Stöffler, Elucidatio fabricae ususque astrolabii (Oppenheim, 1513) Broad Sheet is produced by the Museum of the History of Science, Broad Street, Oxford OX1 3AZ 3. Paper astrolabe by Peter Jordan, Mainz, 1535, included in his edition of Stöffler’s Elucidatio Tel +44(0)1865 277280 Fax +44(0)1865 277288 Web: www.mhs.ox.ac.uk Email: [email protected] 4. Armillary sphere by Carlo Plato, 1588, Rome, MHS inventory no. 45453 5. Celestial globe by Johann Schöner, c.1534 6. Johann Schöner, Globi stelliferi, sive sphaerae stellarum fixarum usus et explicationes (Nuremberg, 1533) 7. Johann Schöner, Tabulae astronomicae (Nuremberg, 1536) 8. Johann Schöner, Opera mathematica (Nuremberg, 1561) THE 9. Astrolabe by Georg Hartmann, Nuremberg, 1527, MHS inventory no. 38642 10. Astrolabe by Johann Wagner, Nuremberg, 1538, MHS inventory no. 40443 11. Astrolabe by Georg Hartmann (wood and paper), Nuremberg, 1542, MHS inventory no. 49296 12. Diptych dial by Georg Hartmann, Nuremberg, 1562, MHS inventory no. 81528 enaissance 13. Lower leaf of a diptych dial with city view of Nuremberg, by Johann Gebhart, Nuremberg, c.1550, MHS inventory no. 58226 14. Peter Apian, Astronomicum Caesareum (Ingolstadt, 1540) R 15. Nicolaus Copernicus, De revolutionibus orbium cœlestium (Nuremberg, 1543) 16. Georg Joachim Rheticus, Narratio prima (Basel, 1566), printed with the second edition of Copernicus, De revolutionibus inAstronomy 17. -

Al-Kindi, a Ninth-Century Physician, Philosopher, And

AL-KINDI, A NINTH-CENTURY PHYSICIAN, PHILOSOPHER, AND SCHOLAR by SAMI HAMARNEH FROM 9-12 December, I962, the Ministry of Guidance in Iraq celebrated the thousandth anniversary of one of the greatest intellectual figures of ninth century Baghdad, Abui Yuisuf Ya'qiib ibn Ishaq al-Kind? (Latin Alkindus).1 However, in the aftermath ofthis commendable effort, no adequate coverage of al-Kindl as a physician-philosopher ofardent scholarship has, to my knowledge, been undertaken. This paper, therefore, is intended to shed light on his intel- lectual contributions within the framework of the environment and time in which he lived. My proposals and conclusions are mainly based upon a study of al-Kindi's extant scientific and philosophical writings, and on scattered information in the literature of the period. These historical records reveal that al-Kindi was the only man in medieval Islam to be called 'the philosopher of the Arabs'.2 This honorary title was apparently conferred upon him as early as the tenth century if not during his lifetime in the ninth. He lived in the Abbasids' capital during a time of high achievement. As one of the rare intellectual geniuses of the century, he con- tributed substantially to this great literary, philosophic, and scientific activity, which included all the then known branches of human knowledge. Very little is known for certain about the personal life of al-Kind?. Several references in the literary legacy ofIslam, however, have assisted in the attempt to speculate intelligently about the man. Most historians of the period confirm the fact that al-Kindl was of pure Arab stock and a rightful descendant of Kindah (or Kindat al-Muliuk), originally a royal south-Arabian tribe3. -

Origins of Astrolabe Theory the Origins of the Astrolabe Were in Classical Greece

What is an Astrolabe? The astrolabe is a very ancient astronomical computer for solving problems relating to time and the position of the Sun and stars in the sky. Several types of astrolabes have been made. By far the most popular type is the planispheric astrolabe, on which the celestial sphere is projected onto the plane of the equator. A typical old astrolabe was made of brass and was about 6 inches (15 cm) in diameter, although much larger and smaller ones were made. Astrolabes are used to show how the sky looks at a specific place at a given time. This is done by drawing the sky on the face of the astrolabe and marking it so positions in the sky are easy to find. To use an astrolabe, you adjust the moveable components to a specific date and time. Once set, the entire sky, both visible and invisible, is represented on the face of the instrument. This allows a great many astronomical problems to be solved in a very visual way. Typical uses of the astrolabe include finding the time during the day or night, finding the time of a celestial event such as sunrise or sunset and as a handy reference of celestial positions. Astrolabes were also one of the basic astronomy education tools in the late Middle Ages. Old instruments were also used for astrological purposes. The typical astrolabe was not a navigational instrument although an instrument called the mariner's astrolabe was widely used. The mariner's astrolabe is simply a ring marked in degrees for measuring celestial altitudes. -

A Classified Bibliography on the History of Scientific Instruments by G.L'e

A Classified Bibliography on the History of Scientific Instruments by G.L'E. Turner and D.J. Bryden Originally published in 1997, this Classified Bibliography is "Based on the SIC Annual Bibliographies of books, pamphlets, catalogues and articles on studies of historic scientific instruments, compiled by G.L'E. Turner, 1983 to 1995, and issued by the Scientific Instrument Commission. Classified and edited by D.J. Bryden" (text from the inside cover page of the original printed document). Dates for items in this bibliography range from 1979 to 1996. The following "Acknowledgments" text is from page iv of the original printed document: The compiler thanks the many colleagues throughout the world who over the years have drawn his attention to publications for inclusion in the Annual Bibliography. The editor thanks Miss Veronica Thomson for capturing on disc the first 6 bibliographies. G.L'E. Turner, Oxford D.J. Bryden, Edinburgh April 1997 ASTROLABE ACKERMANN, S., ‘Mutabor: Die Umarbeitung eines mittelalterlichen Astrolabs im 17. Jahrhundert’, in: von GOTSTEDTER, A. (ed), Ad Radices: Festband zum fünfzigjährrigen Bestehen des Instituts für Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften der Johann Wolfgang Goethe- Universtät Frankfurt am Main (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1994), 193-209. ARCHINARD, M., Astrolabe (Geneva: Musée d'histoire des Sciences de Genève, 1983). 40pp. BORST, A., Astrolab und Klosterreform an der Jahrtausendwende (Heidelberg: Carl Winter Universitatsverlag, 1989) (Sitzungsberichte der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften Philosophisch-historische Klasse). 134pp. BROUGHTON, P., ‘The Christian Island "Astrolabe" ’, Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, 80, no.3 (1986), 142-53. DEKKER, E., ‘An Unrecorded Medieval Astrolabe Quadrant c.1300’, Annals of Science, 52 (1995), 1-47. -

Science and Technology in Medieval Islam

Museum of the History of Science Science and Islam Introduction to Astronomy in Islam Science and Learning in Medieval Islam • Early Islamic teaching encouraged the pursuit of all knowledge that helped to improve people’s lives • Muslims translated important works from ancient Greece and Egypt - Arabic became the international language of scholarship • Huge libraries were established in big cities like Baghdad, Cairo and Damascus Astronomy Astronomy was important to Muslims for practical reasons: • Observations of the sun and moon were used to determine prayer times and an accurate calendar • Astronomical observations were important for purposes of navigation • Astronomical observations were import for the practice of astrology Raj Jai Singh II’s observatory (C18th) in Jaipur, India Large observatories were established and new instruments such as the astrolabe were developed Ottoman observatory 1781 Photograph: The Whipple Museum, Cambridge The quadrant The quadrant is an observational instrument used to measure the angle or altitude of a celestial object. Horary quadrants also had markings on one side that would enable the user to calculate the time of day. Armillary sphere The armillary sphere was a model used to demonstrate the motions of the celestial sphere (stars) and the annual path of the sun (the ecliptic). It could also be used to demonstrate the seasons, the path of the sun in the sky for any day of the year, and to make other astronomical calculations. Early Islamic models were based on a model of the Universe established by Ptolemy in which the Earth was placed at the centre. The astrolabe The astrolabe was a type of astronomical calculator and were developed to an extraordinary level of sophistication by early Muslim scholars. -

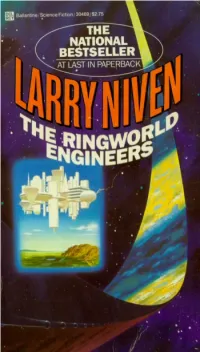

Ringworld Engineers Larry Niven PART ONE CHAPTER 1 UNDER the WIRE

Ringworld 02 Ringworld Engineers Larry Niven PART ONE CHAPTER 1 UNDER THE WIRE Louis Wu was under the wire when two men came to invade his privacy. He was in full lotus position on the lush yellow indoor-grass carpet. His smile was blissful, dreamy. The apartment was small, just one big room. He could see both doors. But, lost in the joy that only a wirehead knows, he never saw them arrive. Suddenly they were there: two pale youths, both over seven feet tall, studying Louis with contemptuous smiles. One snorted and dropped something weapon-shaped in his pocket. They were stepping forward as Louis stood up. It wasn't just the happy smile that fooled them. It was the fist-sized droud that protruded like a black plastic canker from the crown of Louis Wu's head. They were dealing with a current addict, and they knew what to expect. For years the man must have had no thought but for the wire trickling current into the pleasure center of his brain. He would be near starvation from self-neglect. He was small, a foot and a half shorter than either of the invaders. He — As they reached for him Louis bent far sideways, for balance, and kicked once, twice, thrice. One of the invaders was down, curled around himself and not breathing, before the other found the wit to back away. Louis came after him. What held the youth half paralyzed was the abstracted bliss with which Louis came to kill him. Too late, he reached for the stunner he'd pocketed. -

Universal Astrolabe

The Production Guide for the Zarqaliyya (Universal Astrolabe) in the Work of Abu al-Hasan al-Marrakushi Atilla Bir* Saliha Bütün** Mustafa Kaçar*** Âdem Akın**** Translated by Beyza Akatürk***** and Sena Aydın****** Abstract: One of the greatest astronomers of the 13th century, Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥasan al-Marrākushī is the author of Jāmiʿ al-mabādī’ wa-l-ghāyāt fī ʿilm al-mīqāt (An A to Z of Astronomical Timekeeping) which includes the production and operation guides for many astronomical instruments. This study translates the production guide Zarqāliyya, examines the working principle of this instrument, and presents a mathematical interpretation for current readers. A standard astrolabe provides measurements by means of disks produced separately for the different latitudes. The particular disk we examine in this article was developed by the Andalusian astronomer al-Zarqālī (d. 493/1100), is named zarqāliyya, and is known as ṣafīḥa in the West. This disk is peculiar to Islamic astronomy and enables measurement for any latitude. At present, this astrolabe is qualified as universal for being operational independent of latitude. Marrākushī’s discussion of this universal disk zarqāliyya in his time is an epitome for the understanding of the transmission and circulation of knowledge in the scientific environment of Islam, and the current article evaluates this aspect. This article includes the subject and importance of Marrākushī’s monumental work, its modern presentations, and the mathematical explanations of the universal astrolabe’s stereographic projection. It additionally provides the formulations necessary for constructing this astrolabe and presents drawings based on these relations using the Paris edition of the manuscript registered as Or. -

6 • Globes in Renaissance Europe Elly Dekker

6 • Globes in Renaissance Europe Elly Dekker Introduction Abbreviations used in this chapter include: Globes at Greenwich for In 1533 Hans Holbein the Younger, the foremost painter Elly Dekker et al., Globes at Greenwich: A Catalogue of the Globes and then in London, made the portrait now known as The Armillary Spheres in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich (Ox- Ambassadors (fig. 6.1).1 One of the remarkable features ford:OxfordUniversityPressandtheNationalMaritimeMuseum,1999). 1. The best study of the painting and its provenance still is the book of this painting is the abundance of scientific instru- by Mary Frederica Sophia Hervey, Holbein’s “Ambassadors”: The Pic- ments depicted in it. On the top shelf there is a celestial ture and the Men (London: Bell and Sons, 1900). See also Susan Fois- globe, a pillar dial, an equinoctial dial (in two parts), ter, Ashok Roy, and Martin Wyld, Holbein’s Ambassadors (London: a horary quadrant, a polyhedral dial, and, on top of a National Gallery Publications, 1997), esp. 30 – 43; the information book, an astronomical instrument known as a tor- about the globes and the instruments provided in this catalog should be considered with some care. quetum. On the lower shelf there is a terrestrial globe, a 2. The book on arithmetic is that by Peter Apian, titled Eyn newe und book on arithmetic, a set square and a pair of dividers, wolgegründete underweisunge aller Kauffmans Rechnung (Ingolstadt, a lute with broken strings, a case of flutes, and a hymn- 1527), and the hymn book is by Johann Walther [Walter], Geystliche book.2 The objects displayed between the two men are gesangk Buchleyn (Wittenberg, 1525). -

PDF-1 5 May/June 2019 2019 May/June Cedrus Libani

MAY JUNE 2019 6 Cedrus libani Forever? 14 Astrolabe 8SJUUFOBOEQIPUPHSBQIFECZ Sheldon Chad Tech Made … The cedars of Lebanon are symbols of the country itself, a living metaphor of both majestic Not So Easy beauty and endurance that has been tested by empire after axe-wielding empire. But few 8SJUUFOCZ Lee Lawrence cedars remain, and their survival is challenged by warming temperatures and the insects that 1IPUPHSBQITBOEWJEFPCZ David H. Wells follow. Reforestation is bringing new trees to higher, colder altitudes as activists work to *MMVTUSBUJPOTCZ Ivy Johnson extend preserves and biologists look to genetics for adaptations. Even our author pitches in and volunteers a handful of 24-year-old cedar seed cones for analysis—all to keep Cedrus libani About the size of a tablet computer, growing in the hills as well as in the hearts of Lebanon. astrolabes were tools of astronomers, surveyors and navigators, to name a few. But using them took a lot more than typing, tapping and swiping. OnlineCLASSROOM GUIDE 2FIRSTLOOK 4FLAVORS We distribute AramcoWorld in print and online to increase cross-cultural understanding by broadening knowledge of the histories, cultures and geography of the Arab and Muslim worlds and their global connections. aramcoworld.com Front Cover:&BDIBTUSPMBCFTGSPOUQMBUFJTFUDIFEXJUIMJOFTUIBUIFMQDBMDVMBUFTVOSJTF May/June 2019 TVOTFUBOEDFMFTUJBMDPPSEJOBUFTCZSPUBUJOHUIFDBMJCSBUFESFUFPWFSUIFN1IPUP"MBNZ Vol. 70, No. 3 /BWBM.VTFVNPG.BESJE Back Cover:*OUIFNPVOUBJOTPG-FCBOPO DFEBSTEFQFOEPOUIFDPMEPGXJOUFSUPCSFBLPQFO UIFJSTFFET1IPUPCZ(FPSHF"[BS