Hassler-Forest 1 from Flying Man to Falling Man: 9/11 Discourse In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Superman-The Movie: Extended Cut the Music Mystery

SUPERMAN-THE MOVIE: EXTENDED CUT THE MUSIC MYSTERY An exclusive analysis for CapedWonder™.com by Jim Bowers and Bill Williams NOTE FROM JIM BOWERS, EDITOR, CAPEDWONDER™.COM: Hi Fans! Before you begin reading this article, please know that I am thrilled with this new release from the Warner Archive Collection. It is absolutely wonderful to finally be able to enjoy so many fun TV cut scenes in widescreen! I HIGHLY recommend adding this essential home video release to your personal collection; do it soon so the Warner Bros. folks will know that there is still a great deal of interest in vintage films. The release is only on Blu-ray format (for now at least), and only available for purchase on-line Yes! We DO Believe A Man Can Fly! Thanks! Jim It goes without saying that one of John Williams’ most epic and influential film scores of all time is his score for the first “Superman” film. To this day it remains as iconic as the film itself. From the Ruby- Spears animated series to “Seinfeld” to “Smallville” and its reappearance in “Superman Returns”, its status in popular culture continues to resonate. Danny Elfman has also said that it will appear in the forthcoming “Justice League” film. When word was released in September 2017 that Warner Home Video announced plans to release a new two-disc Blu-ray of “Superman” as part of the Warner Archive Collection, fans around the world rejoiced with excitement at the news that the 188-minute extended version of the film - a slightly shorter version of which was first broadcast on ABC-TV on February 7 & 8, 1982 - would be part of the release. -

Heroic Subjectivity in Frank Miller's the Dark Knight

Ruzbeh BABAEE, Kamelia TALEBIAN SEDEHI, Siamak BABAEE* HEROIC SUBJECTIVITY IN FRANK MILLER’S THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS Abstract. The genre of superhero is challenging. How does one explain the subjectivity of the hero with super- powers, morality norms, justice orders and ideologi- cal backgrounds? Many authors and critics interpret superheroes in cultural, political, religious and social contexts. However, none has investigated a superhero’s subjectivity as a dynamic and in-process phenomenon. The present paper examines the relationship between hero and subjectivity through Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns (1986). Miller shows the necessity of subjective dynamics for the sublime in a model of sub- jectivity that echoes with questions about the subject that has flourished within literary, psychoanalytic and linguistic theories since the mid-twentieth century. Thus, this study employs Julia Kristeva’s concept of subject in 199 process with the aim to indicate that subjectivity is a dynamic phenomenon in Miller’s superhero fiction. Keywords: Batman, subjectivity, justice, morality, sub- ject in process Introduction Recently, there has been a near-deafening whir surrounding comic books. This is partly due, of course, to their adaptation into superhero blockbuster films.1 But something else is also going on. There is a diversifi- cation of the content and its readers along race and gender lines. According to a recent interview with Frederick Luis Aldama, the comic book is “a mate- rial history and an aesthetic configuration” that depicts issues of social jus- tice (“Realities of Graphic Novels” 2). Indeed, social justice and race as artic- ulated within the superhero comic book storytelling mode is the focus of several recent PhD, MA and book-length monograph studies. -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations. -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

GRAPHIC NOVELS in ADVANCED ENGLISH/LANGUAGE ARTS CLASSROOMS: a PHENOMENOLOGICAL CASE STUDY Cary Gillenwater a Dissertation Submi

GRAPHIC NOVELS IN ADVANCED ENGLISH/LANGUAGE ARTS CLASSROOMS: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL CASE STUDY Cary Gillenwater A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Education. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Madeleine Grumet James Trier Jeff Greene Lucila Vargas Renee Hobbs © 2012 Cary Gillenwater ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT CARY GILLENWATER: Graphic novels in advanced English/language arts classrooms: A phenomenological case study (Under the direction of Madeleine Grumet) This dissertation is a phenomenological case study of two 12th grade English/language arts (ELA) classrooms where teachers used graphic novels with their advanced students. The primary purpose of this case study was to gain insight into the phenomenon of using graphic novels with these students—a research area that is currently limited. Literature from a variety of disciplines was compared and contrasted with observations, interviews, questionnaires, and structured think-aloud activities for this purpose. The following questions guided the study: (1) What are the prevailing attitudes/opinions held by the ELA teachers who use graphic novels and their students about this medium? (2) What interests do the students have that connect to the phenomenon of comic book/graphic novel reading? (3) How do the teachers and the students make meaning from graphic novels? The findings generally affirmed previous scholarship that the medium of comic books/graphic novels can play a beneficial role in ELA classrooms, encouraging student involvement and ownership of texts and their visual literacy development. The findings also confirmed, however, that teachers must first conceive of literacy as more than just reading and writing phonetic texts if the use of the medium is to be more than just secondary to traditional literacy. -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

Batman Begins Free

FREE BATMAN BEGINS PDF Dennis O'Neil | 305 pages | 15 Jul 2005 | Random House USA Inc | 9780345479464 | English | New York, United States It's Time to Talk About How Goofy 'Batman Begins' Is | GQ As IMDb celebrates its 30th birthday, we have six shows to get you ready for those pivotal years of your life Get some streaming picks. Watch the video. When his parents are killed, billionaire playboy Bruce Wayne relocates to Asia, where he is mentored by Henri Ducard and Batman Begins Al Ghul in how to fight evil. When learning about the plan to wipe out evil in Gotham City by Ducard, Bruce prevents this plan from getting any further and heads back to his home. Back in his original surroundings, Bruce adopts the image of a bat to strike fear into the criminals and Batman Begins corrupt as the icon known as "Batman". But it doesn't stay quiet for long. Written by konstantinwe. I've just come back from a preview screening of Batman Batman Begins. I went in with low expectations, despite the excellence of Christopher Nolan's previous efforts. Talk about having your expectations confounded! This film grips like wet rope from the start. I won't give away any of the story; suffice to say it mixes and matches its sources freely, tossing in a dash of Frank Miller, a bit of Alan Moore and a pinch of Bob Kane to great effect. What's impressive is that despite the weight of the franchise, Nolan has managed to work so many of his trademarks into a mainstream movie. -

The Return of Superman: the Return of Superman Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SUPERMAN THE RETURN OF SUPERMAN: THE RETURN OF SUPERMAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jon Bogdanove,Tom Grummett,Gerard Jones,Dan Jurgens,Karl Kesel,Jeph Loeb | 480 pages | 24 May 2016 | DC Comics | 9781401266622 | English | United States Superman the Return of Superman: The Return of Superman PDF Book Marlon Brando appears posthumously as Jor-El , Superman's biological father. But will he be too late to save Coast City from the clutches of a traitor and the return of the alien warlord, Mongul? He'll take her on a shopping spree to her favorite character store to please her. Batman s Batman. December 23, Seeing Jason seemingly have a slight reaction to Kryptonite, Luthor asks who Jason's father really is; Lois asserts that the father is Richard. Park Hyun-bin Trot singer. The New York Times. While visiting a traditional Korean sauna, Seoeon pulled on older girls to play with him. And then go off to play on his own without waking his family up. Even father Hwijae is put to the side once he sees a cute female. In an attempt to protect the world he loves from cataclysmic destruction, Superman embarks on an epic journey of redemption that takes him from the depths of the ocean to the far reaches of outer space. Following a mysterious absence of several years, the Man of Steel comes back to Earth in the epic action-adventure Superman Returns, a soaring new chapter in the saga of one of the world's most beloved superheroes. The phrase has become a special saying between Hwijae and the triplets. -

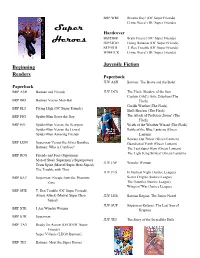

Super Heroes

BRP WRE Bizarro Day! (DC Super Friends) Crime Wave! (DC Super Friends) Super Hardcover B8555BR Brain Freeze! (DC Super Friends) Heroes H2934GO Going Bananas (DC Super Friends) S5395TR T. Rex Trouble (DC Super Friends) W9441CR Crime Wave! (DC Super Friends) Juvenile Fiction Beginning Readers Paperback JUV ASH Batman: The Brave and the Bold Paperback BRP ASH Batman and Friends JUV DCS The Flash: Shadow of the Sun Captain Cold’s Artic Eruption (The BRP BRI Batman Versus Man-Bat Flash) Gorilla Warfare (The Flash) BRP ELI Flying High (DC Super Friends) Shell Shocker (The Flash) BRP FIG Spider-Man Saves the Day The Attack of Professor Zoom! (The Flash) BRP HIL Spider-Man Versus the Scorpion Wrath of the Weather Wizard (The Flash) Spider-Man Versus the Lizard Battle of the Blue Lanterns (Green Spider-Man Amazing Friends Lantern) Beware Our Power (Green Lantern) BRP LEM Superman Versus the Silver Banshee Guardian of Earth (Green Lantern) Batman: Who is Clayface? The Last Super Hero (Green Lantern) The Light King Strikes! (Green Lantern) BRP ROS Friends and Foes (Superman) Man of Steel: Superman’s Superpowers JUV JAF Wonder Woman Team Spirit (Marvel Super Hero Squad) The Trouble with Thor JUV JUS In Darkest Night (Justice League) BRP SAZ Superman: Escape from the Phantom Secret Origins (Justice League) Zone The Gauntlet (Justice League) Wings of War (Justice League) BRP SHE T. Rex Trouble (DC Super Friends) Aliens Attack (Marvel Super Hero JUV LER Batman Begins: The Junior Novel Squad) JUV SUP Superman Returns: The Last Son of BRP STE I Am Wonder -

Thinking About Journalism with Superman 132

Thinking about Journalism with Superman 132 Thinking about Journalism with Superman Matthew C. Ehrlich Professor Department of Journalism University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, IL [email protected] Superman is an icon of American popular culture—variously described as being “better known than the president of the United States [and] more familiar to school children than Abraham Lincoln,” a “triumphant mixture of marketing and imagination, familiar all around the world and re-created for generation after generation,” an “ideal, a hope and a dream, the fantasy of millions,” and a symbol of “our universal longing for perfection, for wisdom and power used in service of the human race.”1 As such, the character offers “clues to hopes and tensions within the current American consciousness,” including the “tensions between our mythic values and the requirements of a democratic society.”2 This paper uses Superman as a way of thinking about journalism, following the tradition of cultural and critical studies that uses media artifacts as tools “to size up the shape, character, and direction of society itself.”3 Superman’s alter ego Clark Kent is of course a reporter for a daily newspaper (and at times for TV news as well), and many of his closest friends and colleagues are also journalists. However, although many scholars have analyzed the Superman mythology, not so many have systematically analyzed what it might say about the real-world press. The paper draws upon Superman’s multiple incarnations over the years in comics, radio, movies, and television in the context of past research and criticism regarding the popular culture phenomenon. -

Clash of the Industry Titans: Marvel, DC and the Battle for Market Dominance

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-21-2013 12:00 AM Clash of the Industry Titans: Marvel, DC and the Battle for Market Dominance Caitlin Foster The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Joseph Wlodarz The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Film Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Caitlin Foster 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Foster, Caitlin, "Clash of the Industry Titans: Marvel, DC and the Battle for Market Dominance" (2013). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1494. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1494 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLASH OF THE INDUSTRY TITANS: MARVEL, DC AND THE BATTLE FOR MARKET DOMINANCE (Thesis format: Monograph) By Caitlin Foster Graduate Program in Film Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Caitlin Foster 2013 Abstract This thesis examines the corporate structures, marketing strategies and economic shifts that have influenced the recent resurgence of the comic book superhero in popular Hollywood cinema. Using their original texts and adaptation films, this study will chronologically examine how each company’s brand identities and corporate structures have reacted to and been shaped by the major cultural and industrial shifts of the past century in its attempt to account for the varying success of these companies throughout their histories. -

St. Jerome's University in the University of Waterloo Department

St. Jerome’s University in the University of Waterloo Department of English ENGL 108A The Superhero Spring 2019 MW 11:30-12:50, EV3 4412 Instructor Information Instructor: Jesse Hutchison Office: Sweeney Hall, Room 2113 Office Hours: TTh 2:30-3:30pm Email: [email protected] Course Description Holy superhero analysis, Batman! In this course, we will look at a variety of ways that the superhero has appeared in literature over the years. We will begin by reading stories about Gilgamesh and Heracles to consider how these early heroic figures influenced the creation of the 20th century American superhero. Throughout the rest of the course, we will concentrate on three superheroes, specifically the DC triumvirate of Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman. We will examine the different ways that these three figures have appeared over the years from their very first appearances in the late 1930s and early 1940s all the way up to today’s versions. The course, then, looks at how events such as WWII, the Cold War, 60s activism, Reaganomics, and 9/11 impacted the way that artists and writers crafted superheroes and told their stories. We will consider the superhero as a social construction that typically embodies (and sometimes questions) the dominant social values and beliefs of their place and time. Along with the early epic poems, the course will look at individual comic book issues, a graphic novel, television episodes, and a film. The course also focuses on how to develop, research, and write an English essay with an argument that is more powerful than a locomotive.