Taliesin West: Wright Apprentices Celebrate 75 Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phoenix Area Homes Include the Circular David Wright House (1952), 5212 East Exeter Blvd., Designed for His Son in North Phoenix (1950), and the H.C

CITY REPORT (Iraq) Opera House (never built), serves as a distinguished gateway to the Tempe campus of Arizona State University. Its president at the time, Grady Gammage, was a good friend of the architect. Wright’s First Christian Church (designed in 1948/built posthumously by the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation in 1973), 6750 N. Seventh Ave., incorporates desert masonry, as in Taliesin West, and features distinctive spires. Wright’s ten distinguished Phoenix area homes include the circular David Wright House (1952), 5212 East Exeter Blvd., designed for his son in north Phoenix (1950), and the H.C. Price House (1954), 7211 N. Tatum Blvd., with its graceful combination of concrete block, steel and copper in a foothills setting. Wright’s approach continued through his pupils, such as Albert Chase McArthur, who is generally credited with the design of the spectacular Arizona Biltmore Hotel (1928), 24th St. and Missouri Ave. Wright’s influence on the building is clear in both massing and details, including the distinctive concrete Biltmore Blocks, cast onsite to an Emry Kopta design. The hotel was Foundation. Photo by Lara Corcoran, courtesy Frank Lloyd Wright restored after a fire in 1973, and additions were built in 1975 and 1979. Blaine Drake was another student who, with Alden Dow, designed the original Phoenix Art Museum, Theater and Library Complex and East Wing (1959, 1965), 1625 N. Central Ave. (Tod Williams and Billie Tsien Architects, New York, designed additions in 1996 and 2006.) Drake also designed the first addition to the Heard Museum (1929), 22 E. Monte Vista Rd., a PHOENIX: UP FROM THE DESERT Spanish Colonial Revival by H.H. -

Reciprocal Sites Membership Program

2015–2016 Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Membership Program The Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Program includes 30 historic sites across the United States. FLWR on your membership card indicates that you enjoy the National Reciprocal sites benefit. Benefits vary from site to site. Please check websites listed in this brochure for detailed information on each site. ALABAMA ARIZONA CALIFORNIA FLORIDA 1 Rosenbaum House 2 Taliesin West 3 Hollyhock House 4 Florida Southern College 601 RIVERVIEW DRIVE 12621 N. FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BLVD BARNSDALL PARK 750 FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT WAY FLORENCE, AL 35630 SCOTTSDALE, AZ 85261-4430 4800 HOLLYWOOD BLVD LAKELAND, FL 33801 256.718.5050 480.860.2700 LOS ANGELES, CA 90027 863.680.4597 ROSENBAUMHOUSE.COM FRANKLLOYDWRIGHT.ORG 323.644.6269 FLSOUTHERN.EDU/FLW WRIGHTINALABAMA.COM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION BARNSDALL.ORG FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: 9AM–4PM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: TOUR HOURS: BOOKSHOP HOURS: 8:30AM–6PM TOUR HOURS: THURS–SUN, 11AM–4PM OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT TOUR TICKETS AVAILABLE AT THE THANKSGIVING, CHRISTMAS AND NEW Experience firsthand Frank Lloyd MAJOR HOLIDAYS. HOLLYHOCK HOUSE VISITOR’S CENTER YEAR’S DAY. 10AM–4PM Wright’s brilliant ability to integrate TUES–SAT, 10AM–4PM IN BARNSDALL PARK. VISITOR CENTER & GIFT SHOP HOURS: SUN, 1PM–4PM indoor and outdoor spaces at Taliesin Hollyhock House is Wright’s first 9:30AM–4:30PM West—Wright’s winter home, school The Rosenbaum House is the only Los Angeles project. Built between and studio from 1937-1959, located Discover the largest collection of Frank Lloyd Wright-designed 1919 and 1923, it represents his on 600 acres of dramatic desert. -

Taliesin West

WELCOME TO TALIESIN WEST PRIVATE EVENTS AT TALIESIN WEST Set in the foothills of the McDowell Mountains, Taliesin West is one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s most personal creations. Wright’s vision and legacy continue to thrive at this unique location. A desert escape just minutes from the resorts of Scottsdale, Taliesin West is unlike any other location in the Valley of the Sun to host your event. Here your guests will have the opportunity to engage with Frank Lloyd Wright’s vision and legacy at the only National Historic site in Scottsdale, and one of two UNESCO World Heritage sites in Arizona. Take a private tour of the property, enjoy a performance on an acoustically perfect stage while sipping a glass of wine, and wow your guests with a dinner overlooking the Valley at sunset. Soak up the history, innovation, and awe that can only be found at Taliesin West. EXPLORE THE VENUES PHOTO BY SUNSHINE & REIGN PHOTOGRAPHY PHOTO BY SUNSHINE & REIGN PHOTOGRAPHY PHOTO BY ANDREW PIELAGE THE CABARET INDOOR Ω SEATS 50 Ω STANDING 60 The Cabaret Theatre is the perfect space for you and your guests to experience the brilliance and delight of a Frank Lloyd Wright design. The unique slope and shape of the room allow for unimpeded views of the small stage below and carry sound perfectly through the space. Perfect for an intimate evening of dining at Wright-designed tables or a performance that offers an PHOTO BY ANDREW PIELAGE exceptional experience found nowhere else. Taliesin West Private Events 2 EXPLORE THE VENUES PHOTO BY TERRY RISHEL GARDEN SQUARES OUTDOOR Ω SEATS 250 Ω STANDING 350 With views of the Music Pavilion, Wright’s Studio, and the McDowell Mountains, the Garden Squares are the perfect venue for groups large or small. -

One Man's Quest to Photograph Every Frank Lloyd Wright Structure Ever Built

One Man's Quest to Photograph Every Frank Lloyd Wright Structure Ever Built architecturaldigest.com /story/frank-lloyd-wright-photographer-andrew-pielage Chris Malloy There are 532 Frank Lloyd Wright structures standing in the world. Phoenix-based photographer Andrew Pielage is on a mission to shoot every one of them. The 39-year-old is the unofficial photographer of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. So far, he has shot about 50 Wright structures. His quest to shoot Wright’s oeuvre began in 2011, when he first toured Taliesin West, Wright’s former winter home and studio outside Phoenix. Photography wasn’t allowed on that tour. But later a friend connected Pielage with the folks at Taliesin West, and for them Pielage shot the sprawling stone-and-wood compound. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation loved his work, and he became its unofficial photographer. Since then, Pielage has shot Wright’s Hollyhock House (Los Angeles), Unity Temple (Illinois), Taliesin (Wisconsin), and Fallingwater (Pennsylvania), where he did a three-week residence. “When you have that much time to shoot a property, you get to know the ins and outs,” he says. What impressed him was how, against the grain of the bright shots one typically sees of the house, Fallingwater, on cloudy days, “turns gray so that the building’s personality changes with the environment.” The spirit of Wright’s organic style, of structures inspired by and seamlessly integrated into the natural world, whether desert or city or forest, has challenged Pielage. How can one properly capture this architectural titan’s work? Pielage has developed tricks. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This Form Is for Use in Nominating Or Requesting Determinations for Individual Properties and Districts

NPS Form 10-900 \M/IVIUJ i ^vy. (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property___________________________________________________________ historic name Wayfarers Chapel ________________________________ other names/site number__________________________________________ 2. Location ___________________________ street & number 5755 Palos Verdes Drive South_______ NA d not for publication city or town Rancho Palos Verdes________________ NAD vicinity state California_______ code CA county Los Angeles. code 037_ zip code 90275 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this C3 nomination D request f fr*d; (termination -

Preserving the Textile Block at Florida Southern College a Report Prepared for the World Monuments Fund Jeffrey M

Preserving the Textile Block at Florida Southern College A Report Prepared for the World Monuments Fund Jeffrey M. Chusid, Preservation Architect 18 September 2009 ISBN-10: 1-890879-43-6 ISBN-13: 978-1-890879-43-3 © 2011 World Monuments Fund 2 Letter from World Monuments Fund President Bonnie Burnham 4 Letter from Florida Southern President Anne B. Kerr, Ph.D. 5 Executive Summary 6 Introduction 7 Preservation Philosophy 7 History and Significance 10 Ideas behind the System 10 Description of the System 10 Conservation Issues with the System in Earlier Sites 13 Recent Conservation Projects at the Storer, Freeman, and Ennis Houses 14 Florida Southern College 16 A History of Changes 18 Site Conditions and Analysis 19 Contents Prior research and observations 19 WMF Site visit 19 Taxonomy of Conservation Problems in the Textile-Block System 20 Issues and Challenges 22 The Textile-Block System 22 The Block 23 Methodologies 24 Conservation 25 Recommendations 26 Appendix A: Visual Conditions Documentation 29 Appendix B: Team Members 38 3 In April 2009, World Monuments Fund was honored to convene a historic gathering of historians, architects, conservators, craftsmen, and scientists at Florida Southern College to explore Frank Lloyd Wright’s use of ornamental concrete textile block construction. To Wright, this material was a highly expressive, decorative, and practical approach to create monumental yet affordable buildings. Indeed, some of his most iconic structures, including the Ennis House in Los Angeles, utilized the textile block system. However, like so many of Wright’s experiments with materials and engineering, textile block has posed major challenges to generations of building owners, architects, and conservators who have struggled with the system’s material and structural performance. -

Zimmerman House Materials—Final List Binder 1

Zimmerman House Materials—Final List Binder 1—Labeled “Zimmerman House Through 1989” Photocopied articles from magazines and newspapers o Dates: from 1956-1989, bulk 1989 Binder 2—Labeled “Zimmerman House 1990” Photocopied and original articles from magazines and newspapers o Date: 1990 Binder 3—Labeled “Zimmerman House 1991” Photocopied and original articles from magazines and newspapers o Dates: 1991-1992, bulk 1991 Box 1—Labeled “Zimmerman House Archive—Deaccession? Files” Folder: Sotheby’s catalogue—Gagliano violin and sales slip Folder: Slides, photos, receipts, correspondence, appraisal for Gagliano violin and bow. o Date: 1989 Box 2—Labeled “Zimmerman House Archive—Vintage Publications on the Zimmerman House” “The Zimmerman House Historic Structure Report” (2 copies); also includes a press release (not attached) o Date: 1989 “A Classic Usonian: Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1950 House for Isadore J. and Lucille Zimmerman.” General information, labels. o Date: 1990 Folder: “Exhibition: A Classic Usonian: Label Copy.” Also an unattached article; label copy from exhibit appears to be the same as previous item. “Currier Grant Application for National Endowment for the Humanities for Training Zimmerman House Guides.” Also includes unattached correspondence, a docent bulletin, a memorandum, and a priorities evaluation. o Dates: 1990-1991, bulk 1990 Box 3—Labeled “Uncatalogued Materials” Newsclipping about Dr. Zimmerman o Date: undated 2 color photos of exterior of Zimmerman House with inscriptions from Zimmermans on back o Date: 1976 Black and white photo of exterior of Zimmerman House in winter o Date: undated 3 B & W photos of Lucille Zimmerman’s family o Date: undated Postcard with picture of S.C. -

Looking for Usonia : Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's Post-1935 Residential Designs As Generators of Cultural Landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University

Masthead Logo Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2006 Looking for Usonia : preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Brown, William Randall, "Looking for Usonia : preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes" (2006). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 18982. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/18982 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Looking for Usonia: Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes by William Randall Brown A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Architectural Studies Program of Study Committee: Arvid Osterberg, Major Professor Daniel Naegele Karen Quance Jeske Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2006 Copyright ©William Randall Brown, 2006. All rights reserved. 11 Graduate C of I ege Iowa State University This i s to certify that the master' s thesis of V~illiam Randall Brown has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University :atures have been redact` 111 LIST OF TABLES iv ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 1 LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK The state of Usonia 8 A brief history of Usonia 9 The evolution of Usonian design 13 Preserving Usonia 19 Toward a cultural landscape 21 METHODOLOGY 26 CASE STUDIES: HOUSE MUSEUMS ON PRIVATE LAND No. -

6.3 Newspaper Article on Improved Charcoal Stoves

INNOVATION, USER PARTICIPATION, AND FOREST ENERGY DEVELOPMENT Matthew S. Gamser A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Science and Technology Policy Studies University of Sussex October 1986 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES DEFINITIONS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS DECLARATION ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION 2. INNOVATION, TECHNICAL CHANGE, AND DEVELOPMENT: THE IMPORTANCE OF USERS 3. RENEWABLE ENERGY AND DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE 4. SUDAN AND THE SUDAN RENEWABLE ENERGY PROJECT 5. IMPROVED CHARCOAL PRODUCTION IN SUDAN 6. CHARCOAL STOVES IN SUDAN: THE MULTIPLE CONTRIBUTIONS OF USERS - ARTISANS, RETAILERS, AND CONSUMERS 7. INSTITUTIONAL INNOVATION AND FORESTRY DEVELOPMENT IN SUDAN 8. INNOVATION AND FOREST ENERGY IN SUDAN: THE INSTITUTIONAL IMPLICATIONS OF THIS TECHNOLOGY DEVELOPMENT EXPERIENCE NOTES BIBLIOGRAPHY APPENDIX 1. GRANTS PROCEDURES APPENDIX 2. CHARCOAL STOVE MONITORING REPORT LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES PAGE FIGURES 2.1 CHANGES IN SUPPLY AND DEMAND 2.2 LINEAR INNOVATION 2.3 NON-LINEAR INNOVATION 2.4 TYPICAL INSTITUTIONAL RELATIONSHIPS FOR TECHNOLOGY DEVELOPMENT: “HIERARCHICAL” MODEL 2.5 INSTITUTIONAL RELATIONSHIPS FOR USER-INTERACTIVE INNOVATION: “BIOLOGICAL” MODEL 3.1 R & D ORGANIZATION CHARTS 4.1 SUDAN 4.2 GOVERNMENT OF SUDAN MINISTERIAL ORGANIZATIONS WITH ENERGY RESPONSIBILITIES 4.3 GOVERNMENT OF SUDAN RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS 4.4 RENEWABLE ENERGY RESEARCH INSTITUTE 4.5 LINES OF AUTHORITY AND SUPPORT IN SREP 5.1 CHARCOAL CONSUMPTION BY REGION 5.2 SUDAN: NORTHERN LIMIT OF CHARCOAL -

Loving Frank

Loving Frank by John Burnham Schwartz Based on the novel by Nancy Horan Escape Artists Draft of: 10/13/09 Lionsgate Entertainment OVER A BLACK SCREEN: THE SOUND OF HAMMERING. EXT. NEW YORK, GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM - DAY (1958) A long, still WIDE SHOT of the museum’s facade: a temple of sculptural perfection. A checker CAB rolls down Fifth Avenue. Then a 1957 CADILLAC, followed by a late 1950’s New York City BUS. TWO MEN in fedoras and suits stroll through frame, stopping briefly to stare up at the building. We PRESS FORWARD into the space where the men just were, closer to the building, CLOSER, passing through the walls... INT. GUGGENHEIM, ATRIUM - CONTINUOUS Inside. WORKMEN and islands of SCAFFOLDING punctuate the vast open atrium. Ethereal light pours down from the huge skylight above. The building is still unfinished. SUPER: 1958. The HAMMERING continues, louder now, mixed with other sounds of CONSTRUCTION. One by one, the workmen stop hammering, doff their caps and stand at respectful attention. FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT, 91 and still arrogantly handsome, dressed in a black broad-brimmed hat and dark suit, stands in the center of the atrium, surveying the space and light. Pleased, but not satisfied. Seeing something that we are not seeing. He nods perfunctorily at the workmen and begins to walk slowly up the long, spiralling RAMP. The workmen stare after him -- the greatest architect of their time -- then return to work. INT. GUGGENHEIM, RAMP - CONTINUOUS Alone, slowly, Frank ascends the ramp. Looking critically at things -- the quality of plasterwork, cavities in the walls and ceilings where lights will be -- but also, the higher he goes, the more he seems to be entering another state of mind, a place of his own. -

VIEWER ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Open Access Annual Acknowledgement of Manuscript Reviewers Daniel Giannella-Neto* and Marilia De Brito Gomes

Giannella-Neto and Gomes Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome 2013, 5:14 DIABETOLOGY & http://www.dmsjournal.com/content/5/1/14 METABOLIC SYNDROME REVIEWER ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Open Access Annual acknowledgement of manuscript reviewers Daniel Giannella-Neto* and Marilia de Brito Gomes Contributing reviewers The Editors of Diabetology and Metabolic Syndrome would like to thank all reviewers, both external and Editorial Board Members, who have contributed to the journal since its inception, and whose valuable support continues to be essential to the success of the journal. Nader Abraham Ather Ali David Araújo-Vilar United States United States Spain Sean Adams Sabrina E M Almeida Ehud Arbit United States Brazil United States Adejuwon Adeneye Marlene M Alvarez Pablo Aschner Nigeria Brazil Colombia Raghu Adya Andion C Alves Yoshimasa Aso United Kingdom Brazil Japan Bharat B Aggarwal Kamal Amin Nimer Assy United States Egypt Israel Navneet Agrawal Amy Anderson Martin Auinger India United States Austria Abelardo Aguilera Christian Andersson Fabienne Aujard Spain Sweden France Bo Ahrén Claudia R M Andrade Navneet Aujla Sweden Brazil United Kingdom Jaweed Akhtar Francesco Andreozzi Márcio Augusto Averbeck United States Italy Brazil Baris Akinci Theodore Angelopoulos Álvaro Avezum Turkey United States Brazil Eduardo Alegria Tiago Antunes-Lopes Daud M. Ishaq Aweis Brazil Brazil Malaysia Adnan A Ali Peter Apor Fereidoun Azizi Canada Hungary Iran * Correspondence: [email protected] Post Graduation Programme in Medicine, Universidade Nove de Julho, Rua Vergueiro, 235-249 – 2º SS, São Paulo 01345-000, Brazil © 2013 Giannella-Neto and Gomes; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

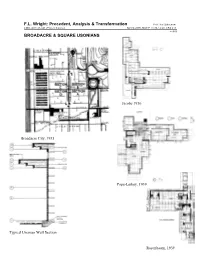

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation BROADACRE

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 BROADACRE & SQUARE USONIANS Jacobs 1936 Broadacre City, 1935 Pope-Leihey, 1939 Typical Usonian Wall Section Rosenbaum, 1939 F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 USONIAN ANALYSIS Sergeant, John. FLW’s Usonian Houses McCarter, Robert. FLW. Ch. 9 Jacobs, Herbert. Building with FLW MacKenzie, Archie. “Rewriting the Natural House,” in Morton, Terry. The Pope-Keihey House McCarter, A Primer on Arch’l Principles P. & S. Hanna. FLW’s Hanna House Burns, John. “Usonian Houses,” in Yesterday’s Houses... De Long, David. Auldbrass. Handlin, David. The Modern Home Reisely, Roland Usonia, New York Wright, Gwendolyn. Building the Dream Rosenbaum, Alvin. Usonia. FLW’s Designs... FLW CHRONOLOGY 1932-1959 1932 FLW Autobiography published, 1st ed. (also 1943, 1977) FLW The Disappearing City published (decentralization advocated) May-Oct. "Modern Architecture" exhibit at MoMA, NY (H.R. Hitchcock & P. Johnson, Int’l Style) Malcolm Wiley Hse., Proj. #1, Minneapolis, MN (revised and built 1934) Oct. Taliesin Fellowship formed, 32 apprentices, additions to Taliesin Bldgs. 1933 Jan. Hitler comes to power in Germany, diaspora to America: Gropius (Harvard, 1937), Mies v.d. Rohe (IIT, 1939), Mendelsohn (Berkeley, 1941), A. Aalto (MIT, 1942) Mar. F.D. Roosevelt inaugurated, New Deal (1933-40) “One hundred days.” 25% unemployment. A.A.A., C.C.C. P.W.A., N.R.A., T.V.A., F.D.I.C.