Application of Bartlett and Morgan's Standards To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syed Saood Zia IT 2017 Hamdard PRR.Pdf

Hybrid Reasoning Approach in Clinical Decision Support Systems By SYED SAOOD ZIA Department of Computer Science A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Information Technology) at Graduate School of Engineering Sciences and Information Technology Faculty of Engineering Sciences and Technology Hamdard University Karachi, Pakistan July, 2016 Copyright c Syed Saood Zia, 2016 All right reserved. Printed by: Hamdard University Graduate School of Engineering Sciences and Information Technology Faculty of Engineering Sciences and Technology Hamdard University Doctoral Defense We hereby recommend that the student SYED SAOOD ZIA Roll No.: ITP - F06 - 104 Enrollment No.: ICK - IT - 06 - 0023 may be accepted for Doctor of Philosophy Degree. Doctoral Defense Committee Held on 26 − 07 − 2017 DD - MM - YYYY Supervisor: P rof. Dr. P ervez Akhtar Signature with Date Co-Supervisor: (if appointed) Signature with Date GEC Member 1: P rof. Dr. Aqeel−ur−Rehman Internal Signature with Date GEC Member 3: Assoc. P rof. Dr. T ariq Javid Ali Internal Signature with Date GEC Member 3: P rof. Dr. Shahid Hafeez Mirza, SSUET, P akistan External GEC Member, Univesity and Country External Evaluator 2: Dr. Nadeem Mahmood, University of Karachi, P akistan Local External Expert Name, Univesity and Country External Evaluator 3: P rof. Dr. Coskun BAY RAK, University of Arkansas, USA Foreign Expert Name, Univesity and Country External Evaluator 4: P rof. Dr. Xiaohong Gao, Middlesex University, UK Foreign Expert Name, Univesity and Country COUNTERSIGNED Dated: DD - MM - YYYY Dean FEST Graduate School of Engineering Sciences and Information Technology Faculty of Engineering Sciences and Technology Hamdard University Certificate of Approval It is certified that Syed Saood Zia s/o Syed Zia Uddin Ahmed bearing enrollment no. -

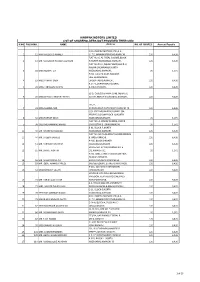

Hinopak Motors Limited List of Shareholders Not Provided Their Cnic S.No Folio No

HINOPAK MOTORS LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS NOT PROVIDED THEIR CNIC S.NO FOLIO NO. NAME Address NO. OF SHARES Amount Payable C/O HINOPAK MOTORS LTD.,D-2, 1 12 MIR MAQSOOD AHMED S.I.T.E.,MANGHOPIR ROAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 FLAT NO. 6, AL-FAZAL SQUARE,BLOCK- 2 13 MR. MANZOOR HUSSAIN QURESHI H,NORTH NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 FLAT NO.19-O, IQBAL PLAZA,BLOCK-O, NAGAN CHOWRANGI,NORTH 3 18 MISS NUSRAT ZIA NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 20 1,071 H.NO. E-13/40,NEAR RAILWAY LINE,GHARIBABAD, 4 19 MISS FARHAT SABA LIAQUATABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 R.177-1,SHARIFABADFEDERAL 5 24 MISS TABASSUM NISHAT B.AREA,KARACHI., 120 6,426 52-D, Q-BLOCK,PAHAR GANJ, NEAR LAL 6 28 MISS SHAKILA ANWAR FATIMA KOTTHI,NORTH NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 171/2, 7 31 MISS SAMINA NAZ AURANGABAD,NAZIMABAD,KARACHI-18. 120 6,426 C/O. SYED MUJAHID HUSSAINP-394, PEOPLES COLONYBLOCK-N, NORTH 8 32 MISS FARHAT ABIDI NAZIMABADKARACHI, 20 1,071 FLAT NO. A-3FARAZ AVENUE, BLOCK- 9 38 SYED MOHAMMAD HAMID 20GULISTAN-E-JOHARKARACHI, 20 1,071 B-91, BLOCK-P,NORTH 10 40 MR. KHURSHID MAJEED NAZIMABAD,KARACHI. 120 6,426 FLAT NO. M-45,AL-AZAM SQUARE,FEDRAL 11 44 MR. SALEEM JAWEED B. AREA,KARACHI., 120 6,426 A-485, BLOCK-DNORTH 12 51 MR. FARRUKH GHAFFAR NAZIMABADKARACHI. 120 6,426 HOUSE NO. D/401,KORANGI NO. 5 13 55 MR. SHAKIL AKHTAR 1/2,KARACHI-31. 20 1,071 H.NO. 3281, STREET NO.10,NEW FIDA HUSSAIN SHAIKHA 14 56 MR. -

(Rfp) for Front End Collection and Disposal of Municipal Solid Waste for Zone Korangi (Dmc Korangi Area) Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan

REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) FOR FRONT END COLLECTION AND DISPOSAL OF MUNICIPAL SOLID WASTE FOR ZONE KORANGI (DMC KORANGI AREA) KARACHI, SINDH, PAKISTAN. Executive Director (Operation-I) Sindh Solid Waste Management Board (SSWMB) Govt. of Sindh SSWMB – NIT-16 Table of Content Sindh Solid Waste Management Board Section-I Preamble Clause# Page# 1.1 Purpose of Request for Proposal 8 1.2 Scope of Work/Assignment 8 1.3 Brief Description of DMC Korangi 8 1.4 MAP of DMC Korangi 9 1.5 Definition & Interpretation 9 1.6 Abbreviation 10 1.7 Section of RFP/Bidding Documents 11 1.8 Procuring Agency Right to cancel any or all proposals/tenders 11 Section-II Instructions to Contractors/Bidders. Clause# Page# 2.1 Information related to procuring agency 13 2.2 Language of proposal and correspondence 13 2.3 Method of Procurement 13 2.4 Period of Contract 13 2.5 Pre-proposal Meeting 13 2.6 Clarification and modifications of Bidding Document 14 2.7 Visit of the area of Service 14 2.8 Utilization of Existing Work Force on SWM of DMC Korangi 14 2.9 Utilization of Existing Solid Waste Collection & Transportation Vehicle of 16 DMC Korangi. 2.10 Utilization of Existing Facilities i.e. Workshop, Offices of DMC Korangi 17 2.11 Amendment through Addendums 17 2.12 Cancelation of Tender before Tender Time 17 2.13 Proposal Preparation Cost/Cost of bidding 17 2.14 Bid submitted by a Joint Venture/Consortium 18 2.15 Place, date, time and manner of submission of Tender/Bid Document 19 2.16 Currency Unit of Offers and Payments 21 2.17 Conditional and Partial Offers 22 2.18 -

Public Notice Auction of Gold Ornament & Valuables

PUBLIC NOTICE AUCTION OF GOLD ORNAMENT & VALUABLES Finance facilities were extended by JS Bank Limited to its customers mentioned below against the security of deposit and pledge of Gold ornaments/valuables. The customers have neglected and failed to repay the finances extended to them by JS Bank Limited along with the mark-up thereon. The current outstanding liability of such customers is mentioned below. Notice is hereby given to the under mentioned customers that if payment of the entire outstanding amount of finance along with mark-up is not made by them to JS Bank Limited within 15 days of the publication of this notice, JS Bank Limited shall auction the Gold ornaments/valuables after issuing public notice regarding the date and time of the public auction and the proceeds realized from such auction shall be applied towards the outstanding amount due and payable by the customers to JS Bank Limited. No further public notice shall be issued to call upon the customers to make payment of the outstanding amounts due and payable to JS Bank as mentioned hereunder: Customer Sr. No. Customer's Name Address Balance as on 12th October 2020 Number 1 1038553 ZAHID HUSSAIN MUHALLA MASANDPURSHI KARPUR SHIKARPUR 327,924 2 1012051 ZEESHAN ALI HYDERI MUHALLA SHIKA RPUR SHIKARPUR PK SHIKARPUR 337,187 3 1008854 NANIK RAM VILLAGE JARWAR PSOT OFFICE JARWAR GHOTKI 65110 PAK SITAN GHOTKI 565,953 4 999474 DARYA KHAN THENDA PO HABIB KOT TALUKA LAKHI DISTRICT SHIKARPU R 781000 SHIKARPUR PAKISTAN SHIKARPUR 298,074 5 352105 ABDUL JABBAR FAZALEELAHI ESTATE S HOP -

Aba Umar Dada Abdul Aziz Kaya

Memon Personalities Aba Umar Dada Late Mr. Dada was a well-known community leader and social worker. He was a prominent member of Karachi Cotton Exchange who earned a name for himself. After the establishment of Pakistan, he settled in the interior of Sindh and took leading part in all social and welfare activities of Hyderabad and Sindh. Settling in Karachi, he continued with his social work and was very active amongst the leaders of the Pakistan Memon Federation. Ahmed H.A. Dada He was a very prominent businessman and an active member of Karachi Stock Exchange rising to the post of its President. He was also on the Local Advisory Committee of National Bank of Pakistan, Karachi Branch, and was popular in the business circles. Abdul Aziz Kaya While in Hyderabad Deccan, he joined Ittehadul Muslimeen under the leadership of Mr. Qasim Rizvi. He worked very actively for the victims of the Indian an-ny. In Karachi, on the advice of Pakistan Ambassador Haji A. Sattar Seth, he was asked to infomi all the Hujjaj about the aims and objects of the creation of Pakistan and as such Haji Aziz started his mission. Durino Haj he rendered noteworthy services to the Hujjaj. He remained involved with his business for a couple of decades and again started his social service activities and established many institutions through which he served the people. During political turmoil when Karachi was under constant curfew for several days at a stretch, he stored consumer products and food products which he supplied at concessive rates without any profit. -

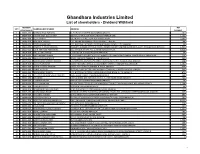

List of Shareholder-Dividend Withheld

Ghandhara Industries Limited List of shareholders - Dividend Withheld MEMBER NET SR # SHAREHOLDER'S NAME ADDRESS FOLIO PAR ID PAYABLE 1 00002-000 MISBAHUDDIN FAROOQI D-151 BLOCK-B NORTH NAZIMABADKARACHI. 461 2 00004-000 FARHAT AFZA BEGUM MST. 166 ABU BAKR BLOCK NEW GARDEN TOWN,LAHORE 1,302 3 00005-000 ALLAH RAKHA 135-MUMTAZ STREETGARHI SHAHOO,LAHORE. 3,293 4 00006-000 AKHTAR A. PERVEZ C/O. AMERICAN EXPRESS CO.87 THE MALL, LAHORE. 180 5 00008-000 DOST MUHAMMAD C/O. NATIONAL MOTORS LIMITEDHUB CHAUKI ROAD, S.I.T.E.KARACHI. 46 6 00010-000 JOSEPH F.P. MASCARENHAS MISQUITA GARDEN CATHOLIC COOP.HOUSING SOCIETY LIMITED BLOCK NO.A-3,OFF: RANDLE ROAD KARACHI. 1,544 7 00013-000 JOHN ANTHONY FERNANDES A-6, ANTHONIAN APT. NO. 1,ADAM ROAD,KARACHI. 5,004 8 00014-000 RIAZ UL HAQ HAMID C-103, BLOCK-XI, FEDERAL.B.AREAKARACHI. 69 9 00015-000 SAIED AHMAD SHAIKH C/O.COMMODORE (RETD) M. RAZI AHMED71/II, KHAYABAN-E-BAHRIA, PHASE-VD.H.A. KARACHI-46. 214 10 00016-000 GHULAM QAMAR KURD 292/8, AZIZABAD FEDERAL B. AREA,KARACHI. 129 11 00017-000 MUHAMMAD QAMAR HUSSAIN C/O.NATIONAL MOTORS LTD.HUB CHAUKI ROAD, S.I.T.E.,P.O.BOX-2706, KARACHI. 218 12 00018-000 AZMAT NAWAZISH AZMAT MOTORS LIMITED, SC-43,CHANDNI CHOWK, STADIUM ROAD,KARACHI. 1,585 13 00021-000 MIRZA HUSSAIN KASHANI HOUSE NO.R-1083/16,FEDERAL B. AREA, KARACHI 434 14 00023-000 RAHAT HUSSAIN PLOT NO.R-483, SECTOR 14-B,SHADMAN TOWN NO.2, NORTH KARACHI,KARACHI. -

Abbreviations and Acronyms

PART II] THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JULY 23, 2019 1505(1) ISLAMABAD, TUESDAY, JULY 23, 2019 PART II Statutory Notifications (S. R. O.) GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN REVENUE DIVISION (Federal Board of Revenue) NOTIFICATIONS Islamabad, the 23rd July, 2019 (INCOME TAX) S.R.O. 829(I)/2019.—In exercise of the powers conferred by sub- section (4) of section 68 of the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001 (XLIX of 2001) and in supersession of its Notification No. S.R.O. 111(I)/2019 dated the lst February, 2019, the Federal Board of Revenue is pleased to notify the value of immoveable properties in columns (3) and (4) of the Table below in respect of areas of Abbottabad classified in column (2) thereof. (2) This notification shall come into force with effect from 24th July, 2019. 1505 (1—211) Price: Rs. 320.00 [1143(2019)/Ex.Gaz.] 1505(2) THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JULY 23, 2019 [PART II ABBOTTABAD Value of Commercial Value of Residential S.No. Areas property per marla property per marla (in Rs.) (in Rs.) (1) (2) (3) (4) 1 Main Bazar, Sadar Bazar, Jinnah Road, Masjid Bazar, 2,580,600 910,800 Sarafa Bazar Gardawara Gali Kutchery Road, Shop and Market. 2 Abbottabad Bazar 2,580,600 759,000 3 Iqbal Road 1,214,400 531,300 4 Mansehra Road 1,973,400 531,300 5 Jinnah Abad 2,277,000 1,062,600 6 Habibullah Colony - 1,062,600 7 Kaghan Colony 759,000 455,400 S.R.O. 830(I)/2019.—In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (4) of section 68 of the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001 (XLIX of 2001) and in supersession of its Notification No. -

SNO Folio Name CNIC/ Incorporation No./ Registration No. Address SHA

UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND WARRANT / SHARES CERTIFICATE INFORMATION PACKAGES LTD CNIC/ Incorporation SHA SNO Folio Name Address Amount No./ Registration RES No. 1 1252 MR.MUHAMMAD DIN - VILLAGE & P.O.CHAK NO.66/12-L, VIA IQBAL NAGAR, TEHSIL CHICHAWATNI, DISTT: SAHIWAL. 13 65,284.04 2 1269 MR. MOHAMMED IQBAL KHAN 42201-8871762-1 SAIMA BOOK STORE AL-AHRAM PLAZA GULSHAN-E-IQBAL KARACHI. 4 1,317.52 3 1283 MISS SHEHZADI BEGUM - 172-A-I, GULBERG III, LAHORE. 349 59,145.10 4 1542 MR.MAHMOOD AHMAD - HOUSE NO-24, STREET NO-24, SECTOR F-11/4, ISLAMABAD. - 21,064.68 5 1640 MR. TAHER ASGERALY BENGALY - A/6, AL-HADI, C.H.S LIMITED, 285, D'CRUZ ROAD, GARDEN EAST, KARACHI. 16 1,620.80 6 1862 MR.SHUJAAT ALI KHAN - C/O S.D.O. T/P YARD(NAVY), 2 FOWLER LINES, KARACHI-4 - 519.00 7 1919 MRS. KHURSHID KHALID - 15-STREET, 88 G-6/3, ISLAMABAD. - 32,593.30 8 1963 MR. ABDULLA - VALIMOHAMMED & CO., 140/14, MURAD KHAN ROAD, KARACHI. 31 6,692.72 9 1968 MR. A.G. MOHAMED VALLI - KAWEY CORPORATION, 3/14, FRERE ROAD, NEW CHALLI, KARACHI. 1 271.11 10 2235 MR. SHAMIM A. ALLAWALA - 8, BAMBINO CHAMBERS GARDEN ROAD KARACHI. - 364.80 11 2236 MR. IKHLAS A. AZIZ - 8, BAMBINO CHAMBERS GARDEN ROAD KARACHI. - 1,564.30 12 2651 MR. A. RASHID SOORTY - C/O ZAHID CORPORATION, 1006-UNITOWERS, I.I. CHUNDRIGAR ROAD P.O. BOX NO.5829, KARACHI-2. - 243.20 13 2694 MST. YASMEEN - A-303 ADAM ARCADE SHAHEED-E-MILLAT ROAD, KARACHI. -

Commecs Affairs Payam-E-Cibe 2018

COMMECS AFFAIRS PAYAM-E-CIBE 2018 Commecs Affairs Independence Day On 14 August 2017, Commecs College celebrated the 70 Independence Day with enthusiasm and patriotism. The program began with the name of Allah and was later carried on by astounding and breathtaking performances by the students of our college which left the audience in awe and renewed the fire of patriotism in their hearts. The English and Urdu speeches were delivered which made the audience hum with delight and stirred a feeling of passion and patriotism within them. The Chief Guest invited on this memorable day was Mr. Javed Jabbar, former Federal Minister and Senator while the Guests of Honor were Mr. Muhammad Sami, a renowned fashion photographer and Mr. Arshad Islam-Member Managing Committee. The day continued by yet another thrilling activity which was the photography contest, organized by the Department of Pakistan Studies, with the theme 'The View from Here'. The first year students as sell as the second year students participated and showed great passion towards their work and showed worth seeing talent. Owais Wahab of Basrai Room took the third prize home, while Imsa Zulfiqar of Toyota Room was the runner up for the contest. The first prize was awarded to Maria Sherwani of Toyota Room. The day came to an end with photography session of all the participants and the prize distribution ceremony while the shields were presented to the guests by our honorable Principal. Komal Ahmed | UDL I Room Defense Day Commecs College celebrated Defense Day on Wednesday, 6 September 2017. The program was organized by the Department of Urdu and was conducted in the morning assembly. -

MQM Exposed 1986-96

CONTENTS Year-wise Details of MQM’s Atrocities (Crimes of Muttahida Qaumi Movement: MQM) .. .. .. 2 Mohajir Qaumi Movement Fact Sheet .. .. .. .. .. 40 Arrests & Arms Recovery From Mqm Workers During December 1998 To February 1999 .. .. .. 59 MQM’s New Drama and The Real Cause of MQM-PML Hostility .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 75 Nazeer Naji Confesses PMLN & Shareef Brethren Helped MQM in 1992 .. .. .. .. .. .. 78 Jinnah Pur & MQM: Major Nadeem Dar also Reveals Stunning Facts .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 80 Where PPP, PML-N and MQM Stood on Jinnahpur in 1992 .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 83 MQM killed 650+ Sind Police Officers .. .. .. .. .. 88 Judge orders deportation of Pakistani party chief .. .. .. 92 PTI’s white paper: MQM accused of killing thousands .. .. .. 94 Running Karachi - from London .. .. .. .. .. .. 95 The Mohajir Qaumi Movement (MQM) In Karachi January 1995-April 1996 .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 98 1 Year-wise Details of MQM’s Atrocities (Crimes of Muttahida Qaumi Movement: MQM) All this were based on newspapers dailies Jang, Jasarat, The News , The Muslim, Nawa-I-Waqt, Frontier Post , The Nation, Dawn , Jang, Pakistan Times and others. 1986 MQM’s first-ever public meeting at Karachi’s Nishtar park on August 8, 1986, was marked by heavy aerial firing from the; pistols and rifles which the party activists were carrying on them. On that day, windowpanes of a traffic police kiosk opposite Quaid-e-Azam’s mausoleum were broken, and stones were pelted on petrol pump near Gurumandir. Addressing the rally, Altaf Hussain said: “Karachi is no more mini-Pakistan. We will accept help no matter where it comes from, from east or west, north or south” ( dailies Jang, Jasarat and other newspapers of August 9, 1986 ). -

Perceptions and Experiences of Men and Women Towards Acceptability and Use of Contraceptives in Underserved Areas of Karachi, Pa

Saleem et al. Reproductive Health (2020) 17:95 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-00946-3 RESEARCH Open Access Perceptions and experiences of men and women towards acceptability and use of contraceptives in underserved areas of Karachi, Pakistan: a midline qualitative assessment of Sukh initiative, Karachi Pakistan Sarah Saleem, Narjis Rizvi, Anam Shahil Feroz* , Sayyeda Reza, Saleem Jessani and Farina Abrejo Abstract Background: Family planning (FP) is an essential component of Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) and contributes directly to SDG targets 3.7 and 5.6. In Pakistan, contraceptive use has remained stagnant over the past 5 years. This change has been very slow when compared to the FP2020 pledge. The Sukh initiative project was conceived and implemented to alleviate these challenges by providing access to quality contraceptive methods in some underserved areas of Karachi, Pakistan. A qualitative study was conducted to understand the perceptions and experiences of men and women towards acceptability and contraceptive use. Methods: A qualitative study was conducted at ten Sukh stations located in four towns of Karachi. Focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted with married women of reproductive age (MWRA) and married men who received FP services through the Sukh initiative. Study participants were purposively sampled for focus group discussions (FGDs). Interview data was manually transcribed and analyzed using thematic analysis. Results: A total of 20 FDGs (Men = 10 FGDs; MWRA = 10 FGDs) were conducted. Three overarching themes were identified: (I) Appropriateness and means to promote contraceptive use; (II) Equity and Accessibility to contraceptives; and (III) Perspective on available FP services. Generally, both men and women were informed about FP methods but women were more cognizant of FP information. -

Directory of Alumni of the Department of Social Work, University of Karachi, Karachi – Pakistan 1 1

Directory of Alumni of the Department of Social Work, University of Karachi, Karachi – Pakistan 1 1 AAMIR WAHEED KHAWAJA Date of Birth: 25 th October, 1966 Official: Block-79, Sindh Secretariat, Directorate of Social Welfare, Government of Sindh, Karachi-Pakistan. Residence: H. No. R-38, Block-8, Yaseenabad, F.B. Area, Karachi-Pakistan. Tel: (Off.) (021) 99204656 (Res.) 36324040 Mobile: 0321-2312080 Email: [email protected] Year of Passing: 1990 Designation: Assistant Director Fields of Child Welfare, Expertise: Community Development & Social Welfare Administration. ABDUL HALEEM Date of Birth: 24 th September, 1980 Official: Health and Nutrition Development Society (HANDS), Karachi Rural, Jamkanda Village, Bin Qasim Town, Karachi-Pakistan. Residence: Old Thana Village, Gadap, Karachi-Pakistan. Tel: (Off.) (021) 34559252, 34532804 (Res.) Mobile: 0333-7003223 Email: [email protected] Year of Passing: 2009 Designation: Community Rehabilitation Worker Fields of Community Development, Expertise: Disabled Persons & Social Case Work. 2 Directory of Alumni of the Department of Social Work, University of Karachi, Karachi – Pakistan ABDUL MAJEED Date of Birth: 17 th July, 1985 Official: Health and Nutrition Development Society (HANDS), Karachi Rural, Jamkanda Village, Bin Qasim Town, Karachi-Pakistan. Residence: Soomar Ismail Village, UC Murad Memon, Gadap, Karachi-Pakistan. Tel: (Off.) (021) 34559252, 34532804 (Res.) Mobile: 0321-2568871 Email: [email protected] Year of Passing: 2008 Designation: District Project Manager Fields of Community Development & Expertise: Youth Welfare. ABDUL NASIR BALOCH Date of Birth: 15 th November, 1959 Official: District Office, Social Welfare Jamshoro, R. B. Colony, Jamshoro, Sindh-Pakistan. Residence: Fl. No. 6, 2nd Floor, Tariq Centre, Near Sattar Masjid, Urdu Bazar, Karachi-Pakistan.