Linear Parks and the Political Ecologies of Permeability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The City Is Almost Entirely Urban (98.9% of the Population). the Population Growth Rate Is Decreasing (In 2010 It Was Only 0.76% Compared to 1.16% in 1990)

URBAN RISK ASSESSMENT CITY SNAPSHOT CITY OF SAO PAULO, BRAZIL Total Population in 2010 (Source: IBGE) 11.253.530 (City) MAP Source: IBGE Census, 2010 Population Growth (% annual) 0,75% Source: SEADE, 2000/2010 Land Area (Km2), Source: SEADE 1,523.3 Km2 Source: IBGE Census, 2010 Population density (per Km2) 7,387.7 inh/Km2 Source: IBGE Census, 2010 Country's per capita GDP (US$) US$ 10,960 Source: Brazil Central Bank and IBGE, 2010. % of country's pop 5.89% (SP City) Source: IBGE Census, 2010 Total number of households 3,576,864 Source: IBGE Census, 2010 Dwelling density (per Km2) Slums: 1.6% Irregular lots: 6.32% Source: SEHAB/HABISP Avg. household income (US$) US$891.37 Source: IBGE Census, 2000 % of Country's GDP 11.7% Source: IBGE Census, 2008 Total Budget (US$) US$ 17,220,088,415.00 Source: City Hall – Budget 2010 Date of last Urban Master Plan 2002 Exchange Rate: R$ 1= US$ 1.66 CITY PROFILE The City is almost entirely urban (98.9% of the population). The population growth rate is decreasing (in 2010 it was only 0.76% compared to 1.16% in 1990). The difference between the numbers of people in the City between day and night could reach two million people. Nevertheless, the population rate in the periphery is 1 increasing (growing from 4.9-5.5 million from 1991-2000), representing 30% of the urban expansion. The periphery concentrates the majority of the poorer inhabitants (the average household income is half the average for the City and the per capita household income is up to three times lower than the City rate). -

Urban Chances in Brazil

CITY REPORT 1 JULY 2013 Urban Chances in Brazil City Reports Guarulhos, Salvador and Rio de Janeiro By Adrian Gurza Lavalle, John Sydenstricker, Júlia Andrade, Denise Vitale, Einar Bratheim, Adriane Batata Table of Contents 1. Overview: Governance and Sustainability in Brazilian Cities . 3 2. Main Urban Growth Strategies – The Role of Mega-Projects in Brazilian Cities . 4 2.1 Guarulhos Growth and the Várzea do Tietê Park . 6 2.2 Rio de Janeiro Growth and the Porto Maravilha . 10 2.3 Salvador Growth and the Regeneration Plan for the Old Downtown . 13 3. Addressing Urban Inequality: Focus on Sub-Standard Settlements . 14 3.1 The Municipality of Rio Janeiro . 16 3.2 The Municipality of Salvador . 20 3.3 The Municipality of Guarulhos . 22 4. Water Governance and Climate Change Issues in Guarulhos . 23 4.1 Major Water Related Climate Vulnerabilities and Disasters in Guarulhos . 24 4.2 Water Availability and Water and Climate Governance in City . 25 4.3 PVT Mega-Project . 26 5. Spatial Knowledge Management: Spatial Perspectives and Participation in Knowledge Production, Exchange and Use? . 27 5.1 Guarulhos Spatial Knowledge Management . 28 5.2 Knowledge Production and Participatory Budget in Guarulhos . 30 6. The Role of Venues of Participation in the City Democratic Governance . 31 6.1 Guarulhos Structure of Participatory Governance and Ruling Parties . 32 6.2 Councils . 33 6.3 Participatory Budgeting . 34 6.4 Salvador Structure of Participatory Governance and Ruling Parties . 35 6.5 Rio de Janeiro Structure of Participatory Governance and -

Mapa Do Transporte Metropolitano - 2014 Metropolitan Transport Network

Mapa do Transporte Metropolitano - 2014 Metropolitan Transport Network Taboão december Jundiaí Aeroporto de Guarulhos Várzea Paulista Campo Limpo Paulista Botujuru Francisco Morato B Guarulhos- CECAP Baltazar Fidélis Vila Galvão embro/ 2012 Franco da Rocha Tucuruvi dez CECAP Caieiras Perus Parada Inglesa Vila Aurora Jd. São Paulo- Jaraguá Ayrton Senna Vila Endres Santana ton Senna yr a A v aulista Engº Pirituba Goular Carandiru Vila No aulista dim Helena-Viladim Mara Romano t Portuguesa-Tietê USP LesteComendador ErmelinoUnião São MiguelJar PItaim P Jar Engº Manoel Feio Piqueri Itaquaquecetuba Bandeirantes Armênia Tiquatira Aracaré Viana Tiradentes vi almeiras- Calmon doso P al Lapa Água Branca Barra Funda Amador Bueno Itape Santa Rita erezinha Altino T Miguel Costa Sampaio Existente Expansão Silveira Belv Brás Imperatriz Engº CarSagradoJandira CoraçãoJd. Jd. BarueriAntonioSta. JoãoCarapicuibaGen. QuitaúnaCom.OsascoPres. Leopoldina Luz Existing Expansion Calmon P oá Estação Modernização Júlio J Ferraz de SuzanoundiapebaBraz CubasMogi dasEstudantes cruzes Station Modernization Prestes Dom BoscoJosé Bonifácio Viana Antonio Gianetti Neto Estação/ Terminal Futuro Estação com elevador Domingos Guaianazes V C de Moraes asconcelos Station/ Future Terminal Station with elevator Km 21 o almeiras- P BresserBelém T Carrão P Vila MatildeGuilhermina-EsperançaP Ar Integração - gratuita São Bento atuapé enha atriar Corinthians- Integração - tarifada Barra Funda tur Alvim Itaquera Deodor Integration - Free Interchange Integration - Paid Interchange ca Mal. -Mooca Ceasa P Integração - gratuita: Horário Especial (veja no site: METRÔ/CPTM) Sé edr Integration - Free Interchange during off-peak hours (see website: METRÔ/CPTM) Santa Cecília o II República Linha 1-Azul: 20,2km Villa-Lobos-Jaguaré Vila Madalena METRÔ Anhangabaú Liberdade Line 1-Blue: 20,2km Mooca Cidade Universitária Higienópolis- Linha 2-Verde: 14,7km METRÔ Clínicas Mackenzie Line 2-Green: 14,7km de Fátima Faria Santuário N. -

Equipamentos De Acessibilidade Nas Estações Da Cptm

M SÃOPAULO Secretaria de CPT GOVERNODO ESTADO Transportes Metropolitanos EQUIPAMENTOS DE ACESSIBILIDADE NAS ESTAÇÕES DA CPTM LEGENDA TODAS AS ESTAÇÕES TRANSPOSIÇÃO ENTRE PLATAFORMA ELEVADOR DA CPTM COMUNICAÇÃO VISUAL XXX 23 ESTAÇÕES ACESSÍVEIS (COM ROTAS ACESSÍVEIS-CERTIFICAÇÃO ABNT) ELEVADOR NÃO PERTENCE A CPTM ESCADA ROLANTE COMUNICAÇÃO SONORA RAMPA DE ACESSO - NORMA ABNT XXX 48 ESTAÇÕES ACESSÍVEIS (ADAPTADAS) RAMPA FORA DA NORMA 7 Jundiaí LINHA TELEFONE PARA SURDO TELEFONE PARA PESSOA EM CADEIRA DE RODAS - PCR 13 LINHA 1 Aeroporto-Guarulhos PISO TÁTIL Várzea Paulista SANITÁRIO MASCULINO ACESSÍVEL SANITÁRIO FEMININO ACESSÍVEL Campo Limpo Paulista SANITÁRIO ACESSÍVEL UNISSEX LINHA Guarulhos-CECAP PASSAGEM EM NÍVEL - ÁREA PAGA Botujurú 1 LINHA PASSAGEM EM NÍVEL - ÁREA LIVRE LINHA PASSAGEM EM NÍVEL RODOVIÁRIA ESTAÇÃO PROVISÓRIA Francisco Morato ESTAÇÃO TEMPORARIAMENTE DESATIVADA INAUGURAÇÃO DA ESTAÇÃO - FASE X Baltazar Fidélis LINHA LINHA Franco da Rocha LINHA LINHA Caieiras LINHA LINHA Perus Vila Aurora LINHA LINHA Jaraguá LINHA eio Engenheiro Cardoso Vila Clarice Comandante Sampaio Gener Amador Bueno Santa Terezinha Santa Pirituba Jardim Silveira Jardim Sagr Santa Rita Jardim Belval al Miguel Costa Antonio João Antonio Piqueri Carapicuiba ado Cor Itapevi Quitaúna ComendadorSão Miguel ErmelinoJardim Paulista Helena-VilaItaim PaulistaJardim Mara RomanoEngenheiroItaquaquecetuba Manoelacaré F Barueri Água Branca Jandira Lapa Ar Calmon Viana Engenheiro Goulart ação 12 12 Lapa Imper Júilio Prestes Domingos de Moraes de Domingos 11 Palmeiras-Barra Funda USP Leste Mogi das Cruzes das Mogi Braz Cubas Braz Estudantes Brás Tatuapé 2 Jundiapeba Suzano 8 Luz Poá atriz Leopoldina atriz Osasco Ferraz de Vasconcelos Dom Bosco Antonio Gianetti Neto Guaianases Presidente Altino Corinthians-Itaquera Bonifácio José Ceasa Juv Ipir entus-Mooca Villa Lobos-Jaguaré anga Tamanduateí Cidade Universitária São Caetano do Sul-Prefeito W Pinheiros Utinga Hebraica-Rebouças LINHA QUANT. -

Sem Título-1

luiz esteves principais projetos 1985/2015 foto: estação tamanduateí | metrô SP ESTUDOS, PROJETOS E CONSULTORIA arquitetura urbanismo paisagismo comunicação visual master plan estudos de viabilidade estudos preliminares projetos funcionais projetos básicos projetos executivos análise e supervisão de projeto coordenação técnica luiz esteves arquitetura o alameda olga, 422 . cj. 94/95 . barra funda . 01155-040 t a são paulo . sp . brasil . 55 11 3868 4078 t [email protected] on www.luizesteves.arq.br c Os projetos de infraestrutura desenvolvidos para o setor público nos últimos 30 anos, com destaque para sistemas de transporte em todo o país, representam o maior volume de trabalhos desenvolvidos em nossa trajetória profissional. O que à primeira vista poderia significar especialização é na verdade um território projetual amplo e variado, transitando-se do desenho urbano até o desenho industrial. Os projetos desenvolvidos nesse período abrangem um conjunto de necessidades de ordem funcional, operacional e técnica cujo grau de complexidade cobrem uma ampla gama de situações, com métodos e sistemas construtivos os mais variados. Essa experiência se estende desde a implantação de grandes empreendimentos a partir da concepção funcional, master plan, estudos de viabilidade, até os projetos básicos e executivos de edificações em geral, estações e terminais de transporte, escolas, parques, centros de controle operacional, centros administrativos, instalações industriais de pátios de manutenção e arquitetura de obras de arte como elevados, pontes, viadutos e passarelas, assim como consultoria, supervisão e análise de projetos. Cabe destacar ainda a forte presença de projetos desenvolvidos em aço, que tem sido de grande valia na simplificação dos processos construtivos e, na busca de uma arquitetura suficiente e capaz de se expressar de forma objetiva. -

Urban Mobility Applied at Comfort Level in Cptm Coral Line Wagons Mobilidade Urbana Aplicada Ao Nível De Conforto Nos Vagões D

URBAN MOBILITY APPLIED AT COMFORT LEVEL IN CPTM CORAL LINE WAGONS MOBILIDADE URBANA APLICADA AO NÍVEL DE CONFORTO NOS VAGÕES DA LINHA CORAL DA CPTM MOVILIDAD URBANA APLICADA AL NIVEL DE CONFORT EN CORAL WAGONS DE CPTM Ed Carlos Mariz1 Jônatas Gomes de Oliveira2 Regis Cortez Bueno3 Received in june 2019 Accepted in july 2020 ABSTRACT The city of São Paulo, the most developed metropolis in Brazil, has become an attractive global hub. It currently has a population of approximately 21 million inhabitants in the metropolitan region. In recent years there has been a substantial increase in the number of inhabitants, a fact that brings a direct correlation to the low rates of urban mobility. Passenger transport is no longer offered with quality, often operating with low levels of comfort, especially during peak hours. The purpose of the research is to measure the number of passengers per m2 in the CPTM train operations, Coral line, in order to verify if the service is offered with quality to its users. The mathematical modeling used was the calculation of fleet sizing. The survey data indicated that the levels are on average nine passengers per square meter, acceptable levels, but well below the standards of developed countries. Keywords: Passenger Transport. Urban Mobility. CPTM. Comfort Level. RESUMO A cidade de São Paulo, metrópole mais desenvolvida do Brasil, tem se tornado um polo atrativo mundial. Conta atualmente com uma população de aproximadamente 21 milhões de habitantes, na região metropolitana. Nos últimos anos tem verificado um aumento substancial em número de habitantes, fato que, traz uma correlação direta aos baixos índices de mobilidade urbana. -

THE GROWTH of BRAZILIAN BAPTIST CHURCHES in METROPOLITAN Sao PAULO: 1981- 1990

THE GROWTH OF BRAZILIAN BAPTIST CHURCHES IN METROPOLITAN sAo PAULO: 1981- 1990 by Donald Edward Price submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Theology in the subject MISSIOLOGY atthe University of South Africa SUPERVISOR: PROF WA SAA YMAN JOINT SUPERVISOR: DR B H BURNS NOVEMBER, 1998 University of South Africa Abstract THE GROWTH OF BRAZILIAN BAPTIST CHURCHES IN METROPOLITAN sAo PAULO: 1981-1990 by Donald Edward Price Chairperson of the Supervisory Committee:Professor Willam A. Saayman Department of Missiology This work endeavors to analyze the growth of Brazilian Baptists in metropolitan Sao Paulo between the last two official censes. Protestants have been accused of not adapting to Brazilian culture, of organizing "mini convents," rather than life and society-transforming communities, of having their roots so deeply embedded in their rural past that they are maladjusted to Brazilian urban life. Is this so? Has the result of over one hundred years of missionary effort been the production of a carbuncle within the Brazilian social fabric, a foreign body that must be rejected - as it rejects its host? Chapter two traces the history of Brazil, and of the insertion of Missionary Protestantism into the Brazilian social fabric. Special emphasis is given to the growth and development of the Brazilian Baptist Convention, especially in the State of Sao Paulo. Finally, the growth of the Brazilian Baptist churches in metropolitan Sao Paulo between the last two censes, 1981-1990, is analyzed. Brazilian Baptists have grown at better than twice the rate of the general population, especially in the urban, residential, communities. -

Cptm Cnpj: 71.832.679/0001-23

GOVERNO DO ESTADO DE SÃO PAULO COMPANHIA PAULISTA DE TRENS METROPOLITANOS - CPTM CNPJ: 71.832.679/0001-23 BALANÇO SOCIAL Palavra da Diretoria 11 - Coral e um para a linha 7 - Rubi. de habitantes, a CPTM prevê a continuidade do Expresso Leste pela linha 11 - Coral no Deixamos 2008 com um saldo bastante positivo e já começamos a contagem regressiva Novos processos de contratação de serviços para a recuperação da frota estão em mesmo padrão de qualidade do serviço ofertado atualmente até Guaianazes. para o fi nal de 2010, quando deveremos ter cumpridas as metas estabelecidas andamento. Destacam-se: Novos trens estão sendo adquiridos e as estações serão modernizadas, incorporando pelo Plano de Expansão. A partir deste ano, a CPTM passará pela maior revolução 1) o programa para a renovação da frota, que opera na linha 8 - Diamante e contará melhorias funcionais adaptadas às exigências de acessibilidade e com adequações tecnológica de sua história, o que exigirá esforço redobrado, comprometimento e, com parceria privada, já aprovada pelo PED e que contempla também a aquisição de 24 viárias no entorno necessárias para qualifi car a integração com outros modos. Estão principalmente, foco naquilo que é essencial para atingirmos esses objetivos. trens novos para essa linha; 2) intervenções de modernização e revisão geral em 276 previstas, ainda, a implantação de novas vias, a requalifi cação de sistemas e a Desde quando assumimos, procuramos dar continuidade ao trabalho iniciado em 2007, carros de diferentes séries de trens. implantação de pátios e ofi cinas. com dois grandes focos que se complementam: o Plano de Expansão, que na CPTM Nessa mesma região, estuda-se também a inovação e concepção de serviço signifi ca a modernização e requalifi cação de suas linhas; e o outro na gestão, voltada Acessibilidade diferenciado, com tecnologia de Metrô Leve, na extremidade leste da linha 11 - Coral para a melhoria contínua da qualidade dos serviços. -

Cptm Dez2017

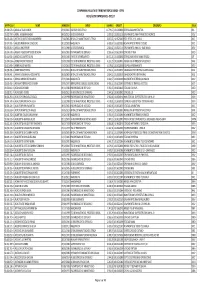

COMPANHIA PAULISTA DE TRENS METROPOLITANOS - CPTM RELAÇÃO DE EMPREGADOS - DEZ/17 MATRICULA NOME ADMISSÃO CARGO SALÁRIO ORGLOT DESCRIÇÃO SIGLA 92.008.674-8 ABDALLA TAIAR JUNIOR 25/06/2012 ASSESSOR EXECUTIVO I 11.799,17 1012400000 GERENCIA ADMINISTRATIVA GFA 92.009.737-5 ABDUL HUSSEIN KARAONI 06/05/2013 AG DE SEGURANCA 2.920,02 1016321110 GRUPAMENTO LINHA 7-FRANCISCO MORATO DOSV 92.005.103-0 ABEDNEGO BATISTA DO NASCIMENTO 27/06/2005 OFICIAL DE MANUTENCAO ELETRICA 3.057,52 1015521005 REDE AEREA 7/10 - MAUA DOLE 92.007.902-4 ABELITO PEREIRA DA CONCEICAO 29/12/2010 MAQUINISTA 3.429,67 1016221005 MOVIMENTO DE TRENS 7/10-LUZ DOC1 92.003.811-5 ABIGAIL DINIZ FREIRE 19/01/1998 AG DE SEGURANCA 2.920,02 1016321210 GRUPAMENTO LINHA 10 - BASE MAUA DOSV 92.004.678-9 ABIGAIL PASSOS SANTOS DE OLIVEIRA 30/06/2000 ENCARREGADO DE ESTACAO 3.935,66 1016630030 ESTACAO UTINGA DOED 92.000.554-3 ABILIO DOS SANTOS SILVA 06/06/1984 CHEFE DE DEPARTAMENTO 18.671,22 1015400000 GERENCIA DE ENG DE MANUTENCAO GOT 92.004.030-6 ABNER AFONSO PADOVEZI 01/09/1998 TEC DE MANUTENCAO, PROJETOS E OBRAS 4.325,29 1015360005 ABRIGO ENG SP-PREVENTIVA ELETRICA DORE 92.010.995-0 ABNER ALVES MENDES 15/07/2014 TEC DE MANUTENCAO, PROJETOS E OBRAS 4.179,02 1015412000 EQUIPE VIA PERMANENTE DOTV 92.008.296-3 ABNER ORRA PEREIRA 13/09/2011 OFICIAL DE MANUTENCAO ELETRICA 2.954,12 1015533030 SINALIZACAO PREVENTIVA CALMON VIANA DOLS 92.006.842-1 ABRAAO JOSE MASALA DOS SANTOS 28/09/2009 OFICIAL DE MANUTENCAO ELETRICA 2.954,12 1015533015 SINALIZACAO PREVENTIVA BRAS DOLS 92.006.531-7 ABRAAO MOURA -

Manual-Codificador-Domiciliar-2007

Pesquisa Origem e Destino 2007 – Manual de Codificação da Pesquisa Domiciliar INTRODUÇÃO Este manual contém o material necessário a complementação da codificação dos questionários da Pesquisa Domiciliar, parte integrante da Pesquisa Origem e Destino 2007. 2 Pesquisa Origem e Destino 2007 – Manual de Codificação da Pesquisa Domiciliar BLOCO 2 Dados sobre o 1º trabalho Ocupação A ocupação declarada pelo entrevistado deve ser classificada dentro de um dos códigos apresentados no Anexo I - Classificação das Ocupações. Anotar o código referente a ocupação no campo de digitação correspondente. 3 Pesquisa Origem e Destino 2007 – Manual de Codificação da Pesquisa Domiciliar Setor de atividade econômica O mesmo ocorre com o setor de atividade econômica descrito pelo entrevistado: anotar no campo destinado a este fim o código correspondente ao setor que o entrevistado trabalha de acordo com o Anexo II – Classificação de Setores de Atividade Econômica. Dados sobre o segundo trabalho As orientações para preenchimento dos dados sobre o segundo trabalho são as mesmas já descritas para o primeiro trabalho. 4 Pesquisa Origem e Destino 2007 – Manual de Codificação da Pesquisa Domiciliar BLOCO 3 11. Locais de Transferência O local de transferência só existe se a pessoa utilizou dois ou mais modos para realizar sua viagem. Classificar os locais declarados de acordo com os códigos constantes do Anexo III – Classificação dos Locais de Transferência. 5 Pesquisa Origem e Destino 2007 – Manual de Codificação da Pesquisa Domiciliar ANEXO I CLASSIFICAÇÃO DAS OCUPAÇÕES -

Social Impact Evaluation of the Lilac Line Project: a Study on the Case of São Paulo Subway System

0 1 Social Impact Evaluation of the Lilac Line Project: A study on the case of São Paulo Subway System A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of Public Policy, The University of Tokyo By Nicolle Aya Konai Master of Public Policy/ Public Administration – International Dual Degree Graduate School of Public Policy, The University of Tokyo School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University in the City of New York Advisor: Professor Toshiro Nishizawa May 2015 2 Abstract The work utilizes propensity score matching and difference-in-differences statistical techniques to develop an evaluation study on the social impacts attributed to the construction and operation of the Lilac Line (Line 5) of the subway system in the city of São Paulo over the 1997-2007 period. The study considers the Origin Destination Survey published by METRO in 1997 and 2007, as well as the Urban Mobility Survey 2012 as the primary data sources. Results show that statistically significant results were found regarding a decrease of 18.6% in the number of owned cars (-0.186, SE: 0.0892) and an increase of the number of generated trips (8,221, SE: 3,807). 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my Advisor, Professor Toshiro Nishizawa, for the encouragement, kind comments and supervision. Also, several Professors at Columbia University who provided me with thoughtful insights on my research, specifically Professor Noha Emara and Professor Eric Verhoogen. I would also like to thank the Graduate School of Public Policy (GraSPP) staff for the administrative support while I was in the US, the METRO for providing me with further information on the surveys, the Mitsubishi UFJ Trust Scholarship Foundation, the Go Global Scholarship (the University of Tokyo), the GoFundMe campaign and the Lemann Foundation for the financial and career support. -

Manual Do Entrevistador

MANUAL COMPLEMENTAR DE CODIFICAÇÃO DA PESQUISA DOMICILIAR AGOSTO – 2012 – v2 Pesquisa de Mobilidade da RMSP – 2012 – Manual de Codificação da Pesquisa Domiciliar INTRODUÇÃO Este manual contém as informações necessárias à complementação da codificação dos questionários da Pesquisa Domiciliar, parte integrante da Pesquisa da Mobilidade da Região Metropolitana de São Paulo - 2012. 1 Pesquisa de Mobilidade da RMSP – 2012 – Manual de Codificação da Pesquisa Domiciliar BLOCO 2 Dados sobre o 1º trabalho Ocupação A ocupação declarada pelo entrevistado deve ser classificada dentro de um dos códigos apresentados no Anexo I - Classificação das Ocupações. Anotar o código referente a ocupação no campo de digitação correspondente. 2 Pesquisa de Mobilidade da RMSP – 2012 – Manual de Codificação da Pesquisa Domiciliar Setor de atividade econômica O mesmo ocorre com o setor de atividade econômica descrito pelo entrevistado: anotar no campo destinado a este fim o código correspondente ao setor que o entrevistado trabalha de acordo com o Anexo II – Classificação de Setores de Atividade Econômica. Dados sobre o 2º trabalho As orientações para preenchimento dos dados sobre o segundo trabalho são as mesmas já descritas para o primeiro trabalho. 3 Pesquisa de Mobilidade da RMSP – 2012 – Manual de Codificação da Pesquisa Domiciliar BLOCO 3 7. Locais de Transferência O local de transferência só existe se a pessoa utilizou dois ou mais modos para realizar sua viagem. Classificar os locais declarados de acordo com os códigos constantes do Anexo III – Classificação