Ballerina: Fashion's Modern Muse Press Release

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

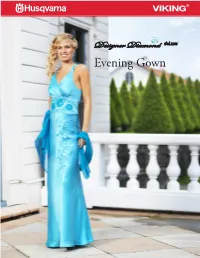

Evening Gown Sewing Supplies Embroidering on Lightweight Silk Satin

Evening Gown Sewing supplies Embroidering on lightweight silk satin The deLuxe Stitch System™ improves the correct balance • HUSQVARNA VIKING® DESIGNER DIAMOND between needle thread and bobbin thread. Thanks to the deLuxe™ sewing and embroidery machine deLuxe Stitch System™ you can now easily embroider • HUSQVARNA VIKING® HUSKYLOCK™ overlock with different kinds of threads in the same design. machine. • Use an Inspira® embroidery needle, size 75 • Pattern for your favourite strap dress. • Turquoise sand-washed silk satin. • Always test your embroidery on scraps of the actual fabric with the stabilizer and threads you will be using • Dark turquoise fabric for applique. before starting your project. • DESIGNER DIAMOND deLuxe™ sewing and • Hoop the fabric with tear-away stabilizer underneath embroidery machine Sampler Designs #1, 2, 3, 4, 5. and if the fabric needs more support use two layers of • HUSQVARNA VIKING® DESIGNER™ Royal Hoop tear-away stabilizer underneath the fabric. 360 x 200, #412 94 45-01 • Endless Embroidery Hoop 180 x 100, #920 051 096 Embroider and Sew • Inspira® Embroidery Needle, size 75 • To insure a good fit, first sew the dress in muslin or • Inspira® Tear-A-Way Stabilizer another similar fabric and make the changes before • Water-Soluble Stabilizer you start to cut and sew in the fashion fabric for the dress. • Various blue embroidery thread Rayon 40 wt • Sulky® Sliver thread • For the bodice front and back pieces you need to embroider the fabric before cutting the pieces. Trace • Metallic thread out the pattern pieces on the fabric so you will know how much area to fill with embroidery design #1. -

Class Descriptions

The Academy of Dance Arts 1524 Centre Circle Downers Grove, Illinois 60515 (630) 495-4940 Email: [email protected] Web Site: www.theacademyofdanceartshome.com DESCRIPTION OF CLASSES All Class Days and Times can be found on the Academy Class Schedule ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ BALLET PROGRAM AND TECHNIQUE CLASSES Ballet is the oldest formal and structured form of dance given the reverence of being the foundation of ALL The Dance Arts. Dancers build proper technical skills, core strength and aplomb, correct posture and usage of arms, head and foremost understand the basics in technique. Students studying Ballet progress in technique for body alignment, pirouettes, jumps, co-ordination skills, and core strength. Weekly classes are held at each level with recommendations for proper advancement and development of skills for each level. Pre-Ballet Beginning at age 5 to 6 years. Students begin the rudiments of basic Ballet Barre work. Focus is on the positions of the feet, basic Port de bras (carriage of the arms), body alignment, and simple basic steps to develop coordination skills and musicality. All this is accomplished in a fun and nurturing environment. Level A Beginning at age 6 to 8 years. Slowly the demanding and regimented nature of true classical Ballet is introduced at this level with ballet barre exercises and age/skill level appropriate center work per Academy Syllabus. When Students are ready to advance to the next level, another Level-A Ballet or B-Ballet class will be recommended per instructor. Level B Two weekly classes are required as the technical skills increase and further steps at the Barre and Center Work and introduced. -

Evening Gown Quilt Mystique

Evening Gown FREE PROJECT SHEET • 888.768.8454 • 468 West Universal Circle Sandy, UT 84070 • www.rileyblakedesigns.com FINISHED QUILT SIZE 56” x 60” Border 1 Measurements include ¼” seam allowance. Cut 5 strips 5½” x WOF from black main Sew with right sides together unless otherwise stated. Border 2 Please check our website www.rileyblakedesigns.com for any Cut 6 strips 3½” x WOF from gray dot revisions before starting this project. This pattern requires a basic knowledge of quilting technique and terminology. QUILT ASSEMBLY Refer to quilt photo for placement of strips. FABRIC REQUIREMENTS 1 yard (90 cm) black main (C3080 Black) Evening Gown Strips ¼ yard (20 cm) white main (C3080 White) Cut each strip 40½” wide. Sew strips together in the following 1/8 yard (10 cm) gray damask (C3081 Gray) order: gray petal, white flower, white dot, white main, black ¼ yard (20 cm) gray flower (C3082 Gray) stripe, white petal, and gray flower. ¼ yard (20 cm) white flower (C3082 White) 1/2 yard (40 cm) gray petal (C3083 Gray) Flower Appliqué ¼ yard (20 cm) white petal (C3083 White) Use your favorite method of appliqué. Refer to quilt photo for 5/8 yard (50 cm) gray dot (C3084 Gray) placement of large, medium, and small flowers and centers. ¼ yard (20 cm) white dot (C3084 White) ¼ yard (20 cm) black stripe (C3085 Black) Borders 1/8 yard (10 cm) clean white solid (C100-01 Clean White) Seam allowances vary so measure through the center of the 1/2 yard (40 cm) slate shade (C200-10 Slate) quilt before cutting border pieces. -

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’S Split Sides

Spring 2012 Ball et Review The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’s Split Sides . © 2012 Dance Research Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. 4 Moscow – Clement Crisp 5 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 6 Oslo – Peter Sparling 9 Washington, D. C. – George Jackson 10 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 12 Toronto – Gary Smith 13 Ann Arbor – Peter Sparling 16 Toronto – Gary Smith 17 New York – George Jackson Ian Spencer Bell 31 18 The Caramel Variations Darrell Wilkins 31 Malakhov’s La Péri Francis Mason 38 Armgard von Bardeleben on Graham Don Daniels 41 The Iron Shoe Joel Lobenthal 64 46 A Conversation with Nicolai Hansen Ballet Review 40.1 Leigh Witchel Spring 2012 51 A Parisian Spring Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino Francis Mason Managing Editor: 55 Erick Hawkins on Graham Roberta Hellman Joseph Houseal Senior Editor: 59 The Ecstatic Flight of Lin Hwa-min Don Daniels Associate Editor: Emily Hite Joel Lobenthal 64 Yvonne Mounsey: Encounters with Mr B 46 Associate Editor: Nicole Dekle Collins Larry Kaplan 71 Psyché and Phèdre Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy Sandra Genter Photographers: 74 Next Wave Tom Brazil Costas 82 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 89 More Balanchine Variations – Jay Rogoff Associates: Peter Anastos 90 Pina – Jeffrey Gantz Robert Gres kovic 92 Body of a Dancer – Jay Rogoff George Jackson 93 Music on Disc – George Dorris Elizabeth Kendall 71 100 Check It Out Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener Sarah C. -

A Brief History of the Evolution of Operating Room Attire

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 1 From formalwear and frocks to scrubs and gowns: A brief history of the evolution of operating room attire AUTHORS Jessica L. Buicko, MD1 Michael A. Lopez, DO1 Miguel A. Lopez-Viego, MD, FACS1 1Department of Surgery, University of Miami-JFK Medical Center, Atlantis, FL CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Jessica L. Buicko 225 NE 1st St #209 Delray Beach, FL 33444 518-229-7711 [email protected] ©2016 by the American College of Surgeons. All rights reserved. CC2016 Poster Competition • From formal wear and frocks to scrubs and gowns • 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Most of the knowledge of the history of surgical Introduction attire is derived from drawings, paintings and Stroll into any operating room and you will find surgeons anecdotal reports. Although conventional adorned in various shades of blues and greens along with their today, “scrubs” were not routinely worn until masks, scrub hats, and surgical gowns. The surgical attire that has become commonplace throughout operating rooms around the mid-20th century. In the 19th century, it the world, has only been around for less than a century. would be commonplace for a surgeon to shrug off his suit jacket, roll up his sleeves, throw on A brief surgical timeline a frock or apron, and begin operating. Over the Prior to 19th century - Surgeons performed operations in their years, surgical garb continues to evolve to make street clothes with the only concessions being the removal of procedures safer for both the patient and the coats and rolling-up of shirt-sleeves during bloody procedures. -

Dance Etiquette Sheet 15

With the exception of dance shoes, many of the required code items and hair supplies are available for sale in our Pro Shop. Welcome! We are so happy to have you in our dance program. Together, we will work to instill a love of dance that can last a lifetime. Please review the following guidelines, and let us know if you have any questions. PROPER ATTIRE: HAIR: For ALL Ballet classes (Dance Tots, PreBallet, Ballet), hair must be pulled away from the face and pinned securely into a ballet bun (no bangs for ages 6 and up). For ALL other classes, hair must be in a ponytail, secured off the shoulders and away from the face. ALL CLASSES: NO LOOSE CLOTHES OVER LEOTARDS! TINY DANCERS: Female – Non-baggy athletic shorts & t-shirt. Dance attire (leotard, tights, ballet slippers**) may be worn if desired. Bare feet. Hair must be pulled away from face into a ponytail. Male – Non-baggy athletic shorts & t-shirt. Bare feet. Parents – Comfortable clothes that you can move in! Bare feet. DANCE TOTS: Female – Light pink leotard*, light pink footed tights**, pink leather ballet slippers*** Male – White t-shirt, black bike shorts or tights, white socks, black ballet slippers PREBALLET: Female – Light blue leotard*, light pink footed tights**, pink leather ballet slippers*** Male - White t-shirt, black bike shorts or tights, white socks, black ballet slippers CLASSICAL BALLET: Female – Black leotard*, light pink footed tights, pink leather ballet slippers** Male – White t-shirt, black bike shorts or tights, white socks, black ballet slippers *All leotards for Dance Tots, PreBallet, and Classical Ballet must be simple in style – preferably tank, cap, or short sleeve. -

Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018

The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Front Cover Image: Textile Detail of an Evening Dress, circa 1950s, Maker Unknown, Middlesex University Fashion Collection, London, England, F2021AB. The Middlesex University Fashion Collection comprises approximately 450 garments for women and men, textiles, accessories including hats, shoes, gloves, and more, plus hundreds of haberdashery items including buttons and trimmings, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Browse the Middlesex University Fashion Collection at https://tinyurl.com/middlesex-fashion. The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Editor–in–Chief Jennifer Daley Editor Scott Hughes Myerly Proofreader Georgina Chappell Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2018 The Association of Dress Historians ISSN 2515–0995 Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession #988749854 The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer reviewed environment. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. -

Proper Attire

2021-2022 Welcome! We are so happy to have you in our dance program. Together, we With the exception of dance shoes, will work to instill a love of dance that can last a lifetime. Please review the many of the required dancewear following guidelines and let us know if you have any questions. items and hair supplies are available for sale in our Pro Shop. PROPER ATTIRE: HAIR: For ALL Ballet classes (Dance Tots, Fairytale Ballerinas, PreBallet, Ballet), hair must be pulled away from the face and pinned securely into a ballet bun (no bangs for ages 6 and up). For ALL other classes, hair must be in a ponytail, secured off the shoulders and away from the face. ------------------------------------------ ------ TEENY DANCERS: Female – Non-baggy athletic/bike shorts & t-shirt. Bare Feet. Dance attire (leotard, tights, ballet slippers**) may be worn if desired. Male – Non-baggy athletic/bike shorts & t-shirt. Bare feet. Parents – Comfortable clothes that you can move in! Bare feet. DANCE TOTS: Female – Light pink leotard*, light pink footed tights**, pink leather ballet slippers*** Male – White t-shirt, black bike shorts or tights, white socks, black ballet slippers PREBALLET: Female – Light blue leotard*, light pink footed tights**, pink leather ballet slippers*** Male - White t-shirt, black bike shorts or tights, white socks, black ballet slippers PRE-TAP/HIP-HOP: Female – Light blue leotard, light pink OR light suntan footed tights**. Tan Tap Shoes / Tan Slip-on Jazz Shoes. • Optional – Girls may also wear light blue or black dance skirt or dance shorts over their leotard & tights. Male - White t-shirt, black bike shorts, Black crew socks. -

Five Pioneering Black Ballerinas

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Five Pioneering Black Ballerinas: ‘We Have to Have a Voice’ These early Dance Theater of Harlem stars met weekly on Zoom — to survive the isolation of the pandemic and to reclaim their role in dance history. The 152nd Street Black Ballet Legacy, from left: Marcia Sells, Sheila Rohan, Gayle McKinney-Griffith, Karlya Shelton-Benjamin and Lydia Abarca-Mitchell. By Karen Valby June 17, 2021 Last May, adrift in a suddenly untethered world, five former ballerinas came together to form the 152nd Street Black Ballet Legacy. Every Tuesday afternoon, they logged onto Zoom from around the country to remember their time together performing with Dance Theater of Harlem, feeling that magical turn in early audiences from skepticism to awe. Life as a pioneer, life in a pandemic: They have been friends for over half a century, and have held each other up through far harder times than this last disorienting year. When people reached for all manners of comfort, something to give purpose or a shape to the days, these five women turned to their shared past. In their cozy, rambling weekly Zoom meetings, punctuated by peals of laughter and occasional tears, they revisited the fabulousness of their former lives. With the 2 background of George Floyd’s murder and a pandemic disproportionately affecting the Black community, the women set their sights on tackling another injustice. They wanted to reinscribe the struggles and feats of those early years at Dance Theater of Harlem into a cultural narrative that seems so often to cast Black excellence aside. “There’s been so much of African American history that’s been denied or pushed to the back,” said Karlya Shelton-Benjamin, 64, who first brought the idea of a legacy council to the other women. -

Valentino's Qatari Owners Acquire French Fashion Brand Balmain 22

Valentino’s Qatari Owners Acquire French Fashion Brand Balmain 22 juin 2016 Bloomberg - Mayhoola for Investments said to pay as much as $563 million - Fashion deal is second this week by Middle Eastern investors Mayhoola for Investments, an investment fund backed by the emir of Qatar, acquired French fashion house Balmain, adding a brand favored by Kim Kardashian to a roster of labels that includes Italy’s Valentino. Financial terms were not disclosed, though a person familiar with the matter said Mayhoola agreed to pay close to 500 million euros ($563 million). The acquisition of 100 percent of Balmain from shareholders including France’s Hivelin family will allow the brand to accelerate its development by opening new stores around the world, advisers Bucephale Finance said in a statement late Tuesday. Balmain has become one of the most talked about fashion brands under creative director Olivier Rousteing, whose Instagram account is peppered with images of reality-television star Kardashian and her family wearing his military-inspired designs. The fashion house, founded by Pierre Balmain in 1945 and revived in 1995 by Alain Hivelin, has enjoyed strong growth since Rousteing joined in 2011, according to the statement. Mayhoola, which describes itself as a Qatari company focused on local and global investments, also owns Valentino, which is considering selling shares in an initial public offering as early as next year after nearly doubling profit on revenue of more than $1 billion in 2015. Mayhoola didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment. The acquisition of Balmain is the second fashion deal this week by Middle Eastern investors after Bahrain investment house Investcorp Bank BSC purchased 55 percent of Italian luxury menswear maker Corneliani SpA. -

Qatari Investment Group Acquires Parisian Fashion House Balmain 22 Juin 2016 the New York Times

Qatari Investment Group Acquires Parisian Fashion House Balmain 22 juin 2016 The New York Times Balmain, the Parisian fashion house beloved by Hollywood, the European jet set and the Kardashian clan, has been bought by a private investment group linked to Qatar’s royal family and that has sought to build a luxury- brand empire. Balmain, a mostly wholesale business, was sold to Mayhoola for Investments after having attracted bids from several other private equity funds, including L Capital, an investment firm backed by the European luxury conglomerate LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton. Mayhoola “will allow the brand to accelerate its development, notably with the opening of new stores abroad,” Bucéphale Finance, the Paris-based boutique mergers and acquisitions firm that advised Balmain shareholders, said in a statement Tuesday evening. The sale will also fund the expansion of Balmain’s accessories business. “After completing this transaction, Mayhoola for Investments will hold 100 percent of Balmain’s capital,” the statement added. The terms of the deal were not immediately disclosed. Balmain’s shareholders included Jean-François Dehecq, the co-founder of the French pharmaceuticals company Sanofi, and the family of the former Balmain chief executive and controlling shareholder Alain Hivelin, who died in 2014 at the age of 71. Balmain has been injected with new fervor under the leadership of its 30-year-old creative director, Olivier Rousteing, whose signature look — leather jackets, tight bandage dresses and lashings of gold, satin and sparkle — has endeared him to film and reality television stars. Mr. Rousteing spearheaded a sellout collaboration with the fast fashion giant H&M last year, and he regularly posts pictures of celebrity friends wearing Balmain on Instagram, where he has 3.4 million followers.