An Environmental Profile of the Badulla District an Environmental Profile of the Badulla District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cover & Back of SLWC Volume 2

Assessment of Risks to Water Bodies due to Residues of Agricultural Fungicide in Intensive Farming Areas in the Up-country of Sri Lanka using an Indicator Model Ransilu C. Watawala1, Janitha A. Liyanage1 and Ananda Mallawatantri2 1Department of Chemistry, University of Kelaniya, Kelaniya, Sri Lanka 2United Nations Development Programme, Colombo, Sri Lanka Introduction Indiscriminate use of agrochemicals poses a major environmental threat to surface and groundwater. Intensive vegetable cultivation on the steep slopes of up-country hills requires extremely high levels of pesticides (insecticides and fungicides) and fertilizers to maintain high yields and profitability. Farmers do not necessarily follow the doses and frequencies recommended in the instructions but apply higher doses more frequently, as they believe that this will increase yields. The implications of these decisions are not considered by farmers due to the lack of information and understanding of the environmental pathways of chemicals after application. In addition, the methods available to account for the variability of soils, climate and other factors influencing the risk of pesticide use are complex. Potato cultivation in Nuwara Eliya, Bandarawela and Welimada Sri Lanka is a good example of the effects of excessive pesticide use. In these areas precipitation exceeds 1,830mm per annum and crops are affected by a number of diseases and insect attacks, such as late blight caused by Phytopthora infestance. The prevailing misty conditions also promote fungal growth requiring famers to use contact and systemic fungicides for prevention. Lack of understanding of pesticide pathways and the desire to ensure that the disease is under control often lead to overdoses and higher frequency application of pesticides. -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

Role of Defence Forces of Sri Lanka During the Covid-19 Outbreak for Nations Branding

Journal of Management Vol. 15, Issue. 2, 2020 ISSN: 1391-8230 47-64 ROLE OF DEFENCE FORCES OF SRI LANKA DURING THE COVID-19 OUTBREAK FOR NATIONS BRANDING Thesara V.P. Jayawardane Department of Industrial Management University of Moratuwa, Moratuwa, Sri Lanka. Abstract World Health Organization (WHO) confirmed of a novel coronavirus on the 12th January 2020, as the cause of a respiratory illness in a cluster of people in Wuhan City, China. Even though the fatality ratio for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is comparatively lower than SARS, the transmission is greater. Therefore, Sri Lankan government requested the general public to practice proper hygiene methods and self- quarantine methods to safeguard from this disease. Quarantine Law in Sri Lanka is governed by the Quarantine and Prevention of Disease Ordinance No 3 of 1897. Defence Forces of Sri Lanka played many roles in the fight against COVID-19 and this research is an overview of the contribution they have made towards battling the COVID-19 successfully. The purpose of this research is to identify the effectiveness of the measures taken by the Sri Lankan government and the tri forces to stop COVID-19 spreading, which will provide an example for other countries to follow on how to prepare, detect, and respond to similar outbreaks, which in turn will contribute towards Nations Branding. This research is a qualitative study mainly undertaken with content analysis of the information extracted from secondary data such as publications of the local and foreign governments, research reports from Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and World Health Organization (WHO), magazines, newspapers, TV programmes and websites. -

ABBN-Final.Pdf

RESTRICTED CONTENTS SERIAL 1 Page 1. Introduction 1 - 4 2. Sri Lanka Army a. Commands 5 b. Branches and Advisors 5 c. Directorates 6 - 7 d. Divisions 7 e. Brigades 7 f. Training Centres 7 - 8 g. Regiments 8 - 9 h. Static Units and Establishments 9 - 10 i. Appointments 10 - 15 j. Rank Structure - Officers 15 - 16 k. Rank Structure - Other Ranks 16 l. Courses (Local and Foreign) All Arms 16 - 18 m. Course (Local and Foreign) Specified to Arms 18 - 21 SERIAL 2 3. Reference Points a. Provinces 22 b. Districts 22 c. Important Townships 23 - 25 SERIAL 3 4. General Abbreviations 26 - 70 SERIAL 4 5. Sri Lanka Navy a. Commands 71 i RESTRICTED RESTRICTED b. Classes of Ships/ Craft (Units) 71 - 72 c. Training Centres/ Establishments and Bases 72 d. Branches (Officers) 72 e. Branches (Sailors) 73 f. Branch Identification Prefix 73 - 74 g. Rank Structure - Officers 74 h. Rank Structure - Other Ranks 74 SERIAL 5 6. Sri Lanka Air Force a. Commands 75 b. Directorates 75 c. Branches 75 - 76 d. Air Force Bases 76 e. Air Force Stations 76 f. Technical Support Formation Commands 76 g. Logistical and Administrative Support Formation Commands 77 h. Training Formation Commands 77 i. Rank Structure Officers 77 j. Rank Structure Other Ranks 78 SERIAL 6 7. Joint Services a. Commands 79 b. Training 79 ii RESTRICTED RESTRICTED INTRODUCTION USE OF ABBREVIATIONS, ACRONYMS AND INITIALISMS 1. The word abbreviations originated from Latin word “brevis” which means “short”. Abbreviations, acronyms and initialisms are a shortened form of group of letters taken from a word or phrase which helps to reduce time and space. -

Update UNHCR/CDR Background Paper on Sri Lanka

NATIONS UNIES UNITED NATIONS HAUT COMMISSARIAT HIGH COMMISSIONER POUR LES REFUGIES FOR REFUGEES BACKGROUND PAPER ON REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS FROM Sri Lanka UNHCR CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH GENEVA, JUNE 2001 THIS INFORMATION PAPER WAS PREPARED IN THE COUNTRY RESEARCH AND ANALYSIS UNIT OF UNHCR’S CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH ON THE BASIS OF PUBLICLY AVAILABLE INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND COMMENT, IN COLLABORATION WITH THE UNHCR STATISTICAL UNIT. ALL SOURCES ARE CITED. THIS PAPER IS NOT, AND DOES NOT, PURPORT TO BE, FULLY EXHAUSTIVE WITH REGARD TO CONDITIONS IN THE COUNTRY SURVEYED, OR CONCLUSIVE AS TO THE MERITS OF ANY PARTICULAR CLAIM TO REFUGEE STATUS OR ASYLUM. ISSN 1020-8410 Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS.............................................................................................................................. 3 1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... 4 2 MAJOR POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS IN SRI LANKA SINCE MARCH 1999................ 7 3 LEGAL CONTEXT...................................................................................................................... 17 3.1 International Legal Context ................................................................................................. 17 3.2 National Legal Context........................................................................................................ 19 4 REVIEW OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION............................................................... -

Evaluation of Agriculture and Natural Resources Sector in Sri Lanka

Evaluation Working Paper Sri Lanka Country Assistance Program Evaluation: Agriculture and Natural Resources Sector Assistance Evaluation August 2007 Supplementary Appendix A Operations Evaluation Department CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 01 August 2007) Currency Unit — Sri Lanka rupee (SLR) SLR1.00 = $0.0089 $1.00 = SLR111.78 ABBREVIATIONS ADB — Asian Development Bank GDP — gross domestic product ha — hectare kg — kilogram TA — technical assistance UNDP — United Nations Development Programme NOTE In this report, “$” refers to US dollars. Director General Bruce Murray, Operations Evaluation Department (OED) Director R. Keith Leonard, Operations Evaluation Division 1, OED Evaluation Team Leader Njoman Bestari, Principal Evaluation Specialist Operations Evaluation Division 1, OED Operations Evaluation Department CONTENTS Page Maps ii A. Scope and Purpose 1 B. Sector Context 1 C. The Country Sector Strategy and Program of ADB 11 1. ADB’s Sector Strategies in the Country 11 2. ADB’s Sector Assistance Program 15 D. Assessment of ADB’s Sector Strategy and Assistance Program 19 E. ADB’s Performance in the Sector 27 F. Identified Lessons 28 1. Major Lessons 28 2. Other Lessons 29 G. Future Challenges and Opportunities 30 Appendix Positioning of ADB’s Agriculture and Natural Resources Sector Strategies in Sri Lanka 33 Njoman Bestari (team leader, principal evaluation specialist), Alvin C. Morales (evaluation officer), and Brenda Katon (consultant, evaluation research associate) prepared this evaluation working paper. Caren Joy Mongcopa (senior operations evaluation assistant) provided administrative and research assistance to the evaluation team. The guidelines formally adopted by the Operations Evaluation Department (OED) on avoiding conflict of interest in its independent evaluations were observed in the preparation of this report. -

MICE-Proposal-Sri-Lanka-Part-2.Pdf

Sri Lanka East Coast Region Trincomalee , a port city on the northeast coast of Sri Lanka. Set on a peninsula, Fort Frederick was built by the Portuguese in the 17th century. Trincomalee is one of the main centers of Tamil speaking culture on the island. The beaches are used for scuba diving, snorkeling and whale watching. The city also has the largest Dutch Fort in Sri Lanka. Best for: blue-whale watching. Arugam Bay, Arugam Bay is a unique and spectacular golden sandy beach on the East coast, located close to Pottuvil in the Ampara district. It is one of the best surfing spots in the world and hosts a number of international surfing competitions. Best for: Surfing & Ethnic Charm The beach of Pasikudah, which boasts one of the longest stretches of shallow coastline in the world. Sri Lanka ‘s Cultural Triangle Sri Lanka’s Cultural triangle is situated in the centre of the island and covers an area which includes 5 World Heritage cultural sites(UNESCO) of the Sacred City of Anuradhapura, the Ancient City of Polonnaruwa, the Ancient City of Sigiriya, the Ancient City of Dambulla and the Sacred City of Kandy. Due to the constructions and associated historical events, some of which are millennia old, these sites are of high universal value; they are visited by many pilgrims, both laymen and the clergy (prominently Buddhist), as well as by local and foreign tourists. Kandy the second largest city in Sri- Lanka and a UNESCO world heritage site, due its rich, vibrant culture and history. This historic city was the Royal Capital during the 16th century and maintains its sanctified glory predominantly due to the sacred temples. -

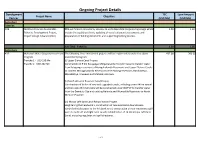

Ongoing Project Details

Ongoing Project Details Development TEC Loan Amount Project Name Objective Partner (USD Mn) (USD Mn) Agriculture Fisheries ADB Northern Province Sustainable PDA will finance consultancy services to undertake detail engineering design which 1.59 1.30 Fisheries Development Project, include the updating of cost, updating of social safeguard assessments and Project Design Advance (PDA) preparation of bidding documents and supporting bidding process. Sub Total - Fisheries 1.59 1.30 Agriculture ADB Mahaweli Water Security Investment The following three investment projects will be implemented under the above 432.00 360.00 Program investment program. Tranche 1 - USD 190 Mn (i) Upper Elahera Canal Project Tranche 2- USD 242 Mn Construction of 9 km Kaluganga-Morgahakanda Transfer Canal to transfer water from Kaluganga reservoir to Moragahakanda Reservoirs and Upper Elehera Canals to connect Moragahakanda Reservoir to the existing reservoirs; Huruluwewa, Manakattiya, Eruwewa and Mahakanadarawa. (ii) North Western Province Canal Project Construction of 96 km of new and upgraded canals, including a new 940 m tunnel and two new 25 m tall dams will be constructed under NWPCP to transfer water from the Dambulu Oya and existing Nalanda and Wemedilla Reservoirs to North Western Province. (iii) Minipe Left Bank Canal Rehabilitation Project Heightening the headwork’s, construction of new automatic downstream- controlled intake gates to the left bank canal; construction of new emergency spill weirs to both left and right bank canals; rehabilitation of 74 km Minipe Left Bank Canal, including regulator and spill structures. 1 of 24 Ongoing Project Details Development TEC Loan Amount Project Name Objective Partner (USD Mn) (USD Mn) IDA Agriculture Sector Modernization Objective is to support increasing Agricultural productivity, improving market 125.00 125.00 Project access and enhancing value addition of small holder farmers and agribusinesses in the project areas. -

OATLAND by JETWING No. 124, St. Andrew's Drive, Nuwara Eliya, Sri

OATLAND BY JETWING No. 124, St. Andrew’s Drive, Nuwara Eliya, Sri Lanka Reservations: +94 11 4709400 Bungalow: + 94 52 222 2445, +94 52 222 2572 Fax: +94 11 2345729 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.jetwinghotels.com General Manager: Mr. Upul Leukebandara 1. INTRODUCTION Oatland by Jetwing sits 6,200 feet above sea level cradled amidst the mist covered highlands of Nuwara Eliya. This colonial bungalow preserves the charm of a bygone era with an ambience that exudes its own exquisite character while offering guests the non-hotel, private house experience. 2. LOCATION The drive up to the Oatland by Jetwing is a scenic one, with lush greenery, waterfalls, tea plantations and majestic mountains. It is approximately 170 km (5 hours) from the Bandaranaike International Airport. It is just a short stroll away from Nuwara Eliya City and Jetwing St. Andrew’s. 3. ROOMS The rooms at Oatland by Jetwing boast modern facilities with colonial architecture. Discover the charms of traditional bed chambers. 3.1 Total Number of Room ROOMS UNITS AREA Room - 20.2 sq.m. Deluxe 04 Bathroom - 5.7 sq.m. Total – 25.9 sq.m. 3.2 Room Facilities • Individual heating units • Bathroom with shower and hot and cold water • Electric power – 220v to 240v • Tea and coffee making facility • Bottled water • Electronic safe • Hair dryer • Iron and ironing board • Telephone 3.3 Room Facilities on Request • Baby cots 4. DINING There is a host of dining experiences at Oatland by Jetwing which includes a 20 sq.m. dining room as well as an al fresco dining area in the garden. -

Sri Lanka Army

RESTRICTED SRI LANKA ARMY ANNUAL REPORT 2005 RESTRICTED RESTRICTED AHQ/DSD/12 ( ) Secretary Ministry Of Defence ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT SRI LANKA ARMY 2005 1. details are forwarded herewith as per the annexure attached here to: a. General Staff Matters. (1) Military operation conducted by the Sri Lanka Army - Annexure „A‟ (2) Training conducted by the Sri Lanka Army - Annexure „ B‟ (3) Financial Matters - Annexure „ C‟ (4) Sports Activities - Annexure „D‟ b. Administrative / Logistic Staff Matters. (1) Administrative matters - progress 2005 - Annexure „E‟ (2) Progress of welfare Activities - Annexure „F‟ (3) Medical - Annexure „G‟ (4) Supply and Transport - Annexure „H‟ (5) Engineer Matters - Annexure „I‟ (6) Land, Air and Naval Facilities - Annexure „J‟ (7) Details of Enlistment - Annexure „K‟ (8) Pay and Allowances - Annexure „L‟ (9) Miscellaneous - Annexure „M‟ GSC FONSEKA RWP RSP rcds psc Lieutenant General Commander of the Army Authenticated by : MCMP SAMARASINGHE RWP RSP USP psc Brigadier Director General General Staff 1 RESTRICTED RESTRICTED GENERAL 1. The objective of publishing this Annual Report is to produce an analysis into General Staff. Administrative and logistic matters carried out by Directorates of Army Headquarters and other establishment during year 2005 and also lapses observed due to certain constraints. 2. Assignments completed and proposals for the following year by respective authorities have been included in this report with a view to provide a broad insight into events during year 2005 and proposal for year 2006. 3. Certain programmes pre- scheduled for year 2005 had been amended to suit unforeseen demands specially in Security Force Headquarters (Jaffna), Security Force Headquarters (Wanni) and Security Force Headquarters (East). -

Dry Zone Urban Water and Sanitation Project – Additional Financing (RRP SRI 37381)

Dry Zone Urban Water and Sanitation Project – Additional Financing (RRP SRI 37381) DEVELOPMENT COORDINATION A. Major Development Partners: Strategic Foci and Key Activities 1. In recent years, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the Government of Japan have been the major development partners in water supply. Overall, several bilateral development partners are involved in this sector, including (i) Japan (providing support for Kandy, Colombo, towns north of Colombo, and Eastern Province), (ii) Australia (Ampara), (iii) Denmark (Colombo, Kandy, and Nuwaraeliya), (iv) France (Trincomalee), (v) Belgium (Kolonna–Balangoda), (vi) the United States of America (Badulla and Haliela), and (vii) the Republic of Korea (Hambantota). Details of projects assisted by development partners are in the table below. The World Bank completed a major community water supply and sanitation project in 2010. Details of Projects in Sri Lanka Assisted by the Development Partners, 2003 to Present Development Amount Partner Project Name Duration ($ million) Asian Development Jaffna–Killinochchi Water Supply and Sanitation 2011–2016 164 Bank Dry Zone Water Supply and Sanitation 2009–2014 113 Secondary Towns and Rural Community-Based 259 Water Supply and Sanitation 2003–2014 Greater Colombo Wastewater Management Project 2009–2015 100 Danish International Kelani Right Bank Water Treatment Plant 2008–2010 80 Development Agency Nuwaraeliya District Group Water Supply 2006–2010 45 Towns South of Kandy Water Supply 2005–2010 96 Government of Eastern Coastal Towns of Ampara -

SRI LANKA 2019 the Details

T A V E R N A T R A V E L S P R E S E N T S S R I L A N K A J U N E 2 0 1 9 G R O U P T R I P J U N E 1 - 9 T H , 2 0 1 9 ONLY $1,400 SRI LANKA 2019 the details JUNE 1 - 9 • 2019 $1,400 what's included? This 8 day adventure is jam-packed wit are a mix of local and luxury! The goal is to keep the cost of the trip as low as possible, while still providing an adventure filled trip! WHAT'S INCLUDED WHAT'S NOT INCLUDED - 8 NIGHTS ACCOMMODATION - FLIGHTS IN SHARED ROOMS - VISA - WELCOME DINNER - TRAVEL INSURANCE - 2 MEALS A DAY - DRINKS - PRIVATE DRIVER - PERSONAL - GROUP PHOTOGRAPHER INCIDENTALS EXPENSES - DAILY ACTIVITIES - OPTIONAL ACTIVITIES SRI LANKA JUNE 2019 activities list of example included activities - VI S I T T O L OCAL T EMPL ES AND S T AT UES - GUI DED HI KES - EL EPHANT S AF ARI - COOKI NG CL AS S - YOGA CL AS S - VI S I T T O T EA PL ANT AT I ON the itinerary 8 ACTIVITY FILLED DAYS IN COLOMBO, KANDY, HAPUTALE, ELLA, AND WELIGAMA. BUSTLING CITIES, ROLLING HILLS, SANDY BEACHES.. THIS TRIP COVERS IT ALL! DAY TRIPS ACCOMMODATIONS SIRIGIYA INCLUDE: UDAWALAWE 5 STAR SUITES MIRISSA HOSTELS UNAWATUNA HOMESTAYS GALLE AIRBNB DAY 1 Meet in Colombo Spend the afternoon exploring the city Welcome dinner buffet DAY 2 Early morning pickup for drive to Kandy Explore the bustling city of Kandy with visits to the Bahiravokanda Vihara Buddha, local temples, and the market.