Yoiyama-Kaleidoscope.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IN WHATEVER WRECKAGE REMAINS by Maeve Kirk

In whatever wreckage remains Item Type Thesis Authors Kirk, Maeve Download date 24/09/2021 15:50:49 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/6617 IN WHATEVER WRECKAGE REMAINS By Maeve Kirk RECOMMENDED: Advisory Committee Chair Richard Carr, PhD Chair, Department of English --- ---^ APPROVED: ------ Todd Sherman, MFA IN WHATEVER WRECKAGE REMAINS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree of Masters of Fine Arts by Maeve Kirk, B.A. Fairbanks, Alaska May 2016 Abstract In Whatever Wreckage Remains is a collection of realistically styled short stories that examines both the danger and potential of change. These pieces are driven by the psychology of the men and woman roaming these pages, seeking to provide insight into the unique weight of their personal wreckage. From a woman craving motherhood who combs through forests searching for the unclaimed body of a runaway to a spitfire retiree’s struggle to accept her husband’s failing health, the individuals in these narratives are all navigating transitional spaces in their lives, often unwillingly. Along the way, they must balance the pressures of familial roles, romantic relationships, and personal histories while attempting to reshape their understanding of self. These stories explore the shifting landscape of identity, belonging, and the sometimes conflicting responsibilities we hold to others and to ourselves. v vi Dedication This manuscript is dedicated to my parents, who read me so many stories. vii viii -

Acdsee Proprint

BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID Permit No. 2419 lPE lPITClHl K.C., Mo. FREE FREE VOL. II NO. 1 YOU'LL NEVER GET RICH READING THE PITCH FEBRUARY 1981 FBIIRUARY II The 8-52'5 Meet BUDGBT The Rev. in N.Y. Third World Bit List .ONTHI l ·TRIVIA QUIZ· WHAT? SQt·1E RECORD PRICES ARE ACTUALLY ~~nll .815 m wi. i .••lIIi .... lllallle,~<M0,~ CGt4J~G ·DOWN·?····· S€f ·PAGE: 3. FOR DH AI LS , prizes PAGE 2 THE PENNY PITCH LETTERS Dec. 29,1980 Dear Warren, Over the years, Kansas Attorney General's have done many strange things. Now the Kansas Attorney General wants to stamp out "Mumbo Jumbo." 4128 BROADWAY KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI 64111 Does this mean the "Immoral Minority" (816) 561·1580 will be banned from Kansas? Is being banned from Kansas a hardship? Edi tor ....••..•••.• vifarren Stylus Morris Martin Contributing vlriters this issue: Raytown, Mo. P.S. He probably doesn't like dreadlocks Rev. Dwight Frizzell, Lane & Dave from either. GENCO labs, Blind Teddy Dibble, I-Sheryl, Ie-Roths, Lonesum Chuck, Mr.D-Conn, Le Roi, Rage n i-Rick, P. Minkin, Lindsay Shannon, Mr. P. Keenan, G. Trimble, Jan. 26, 1981 debranderson, M. Olson Dear Editor, Inspiration this issue: How come K. C. radio stations never Fred de Cordova play, The Inmates "I thought I heard a Heartbeat", Roy Buchanan "Dr. Rock & Roll" Peter Green, "Loser Two Times", Marianne r,------:=~--~-__l "I don' t care what they say about Faithfull, "Broken English", etc, etc,? being avant garde or anything else. How come? Frankly, call me square if you want Is this a plot against the "Immoral to. -

The Complete Poetry of James Hearst

The Complete Poetry of James Hearst THE COMPLETE POETRY OF JAMES HEARST Edited by Scott Cawelti Foreword by Nancy Price university of iowa press iowa city University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright ᭧ 2001 by the University of Iowa Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Sara T. Sauers http://www.uiowa.edu/ϳuipress No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach. The publication of this book was generously supported by the University of Iowa Foundation, the College of Humanities and Fine Arts at the University of Northern Iowa, Dr. and Mrs. James McCutcheon, Norman Swanson, and the family of Dr. Robert J. Ward. Permission to print James Hearst’s poetry has been granted by the University of Northern Iowa Foundation, which owns the copyrights to Hearst’s work. Art on page iii by Gary Kelley Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hearst, James, 1900–1983. [Poems] The complete poetry of James Hearst / edited by Scott Cawelti; foreword by Nancy Price. p. cm. Includes index. isbn 0-87745-756-5 (cloth), isbn 0-87745-757-3 (pbk.) I. Cawelti, G. Scott. II. Title. ps3515.e146 a17 2001 811Ј.52—dc21 00-066997 01 02 03 04 05 c 54321 01 02 03 04 05 p 54321 CONTENTS An Introduction to James Hearst by Nancy Price xxix Editor’s Preface xxxiii A journeyman takes what the journey will bring. -

Felix Issue 0854, 1990

Friday 5th October Number 8TT Farnborough Airshow, p8,9 ews, p2,3 Ill 4kkM\ "HUM «Hk£< j^jjEaling Hall Survives Hoax! The future of Clayponds (the new Ealing specification, including alterations to A hoaxer set of the fire alarm in Beit Hall Halls of residence) was decided at comply with security arrangements. The during the Fresher's carnival last Tuesday midnight on Wednesday when contracts cost of the estate is now S10.5M including morning. There was only one security were finally exchanged. furnishing but excluding financing and guard present to deal with the situation. There was pressure on the part of the professional fees. Ben Turner, Union Deputy President vendors, Beazer Homes (South) pic to A few buildings have already been stated that there should have been two complete the deal and this should occur started, including a show home. Building on duty all night. on the 12th October. work continues and should be complete The alarm, which started at 12.15am Part of the delay was due to a covenant at the end of 1991. There are four phases was found to have originated on the on the site forbidding any use but private to the building work and students will be second floor of Beit New Hostel. On this accommodation. The college needed a able to move in as these are completed. floor, however, the alarm bell failed to waiver from the secretary of state before The venture was described by Angus sound. A bell at the top of the West the land could be used for student Fraser, Managing Director of Imperial staircase in the Union Building also failed. -

Collected Essays a Dissertation Presented

Ten Impossible Things Before Daylight: Collected Essays A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Wesley D. Roj August 2016 © 2016 Wesley D. Roj. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Ten Impossible Things Before Daylight: Collected Essays by WESLEY D. ROJ has been approved for the Department of English and the College of Arts and Sciences by Eric LeMay Associate Professor of English Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT ROJ, WESLEY., Ph.D., December 2016, English Ten Impossible Things Before Daylight: Collected Essays Director of Dissertation: Eric LeMay Ten Impossible Things Before Daylight is a collection of essays which turn on experiences with the uncanny, including premonitions, visitations, bizarre coincidences, impactful dreams, and lucky charms. My essays seek to explore a side of the uncanny that is not horrific but instead, eerily invigorating. The lead-off essay “Goodnight Noises” is an uncanny elegy for friend that I knew since childhood who tragically developed severe schizophrenia. My essay is about making sense of his somewhat mysterious disappearance and death. “Far and Wee” is the story of the unplanned rescue of a baby goat that my wife and I found in an ocean while on vacation. Our rescue of the goat led us to many moments of prescience regarding the birth of our firstborn son. The collection is a varied and confessional portrait of my evolving sense of the uncanny and its influence over the red letter days of my life. -

Issue 168.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 168 July Oxford’s Music Magazine 2009 How Oxford was the making of a Brummie balladeer and a violinist from the valleys - interview inside. Plus: news, reviews and six pages of local gigs and festivals. NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 members of The Boredoms as well stoner label Calculon Records at as former-Can frontman Damo www.calculon.co.uk. Following on Suzuki and DJ Scotch Egg. To from Mondo Cada’s demise, Ian NEWNEWSS celebrate 10 years of fundraising and Adam from the band have for Shelter, Audioscope are also formed a new band, Ruins, who Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU planning to release a limited edition debuted at Charlbury Riverside Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] compilation album of exclusive Festival in June. Visit Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net tracks from acts that have www.myspace.com/ruinsonline for performed at the event over the more news on the band. years. BBC OXFORD’S September. The local favourite, Meanwhile, Oxfordbands.com are THISREALITY.COM podcast has INTRODUCING show is offering who has recently relocated to Paris, organising a local bands’ five-a- become the first UK-based podcast one local band a chance to play at releases ‘The Animal’ on Kartel side football tournament to help to be awarded a Limited Online Truck Festival. The dedicated local Records. The album is preceded by raise money for Shelter. The Exploitation Licence by the music show has nabbed a slot on a single, ‘True Love Will Find You tournament will take place over the Performing Rights Society. -

Songs in the Key of Z

covers complete.qxd 7/15/08 9:02 AM Page 1 MUSIC The first book ever about a mutant strain ofZ Songs in theKey of twisted pop that’s so wrong, it’s right! “Iconoclast/upstart Irwin Chusid has written a meticulously researched and passionate cry shedding long-overdue light upon some of the guiltiest musical innocents of the twentieth century. An indispensable classic that defines the indefinable.” –John Zorn “Chusid takes us through the musical looking glass to the other side of the bizarro universe, where pop spelled back- wards is . pop? A fascinating collection of wilder cards and beyond-avant talents.” –Lenny Kaye Irwin Chusid “This book is filled with memorable characters and their preposterous-but-true stories. As a musicologist, essayist, and humorist, Irwin Chusid gives good value for your enter- tainment dollar.” –Marshall Crenshaw Outsider musicians can be the product of damaged DNA, alien abduction, drug fry, demonic possession, or simply sheer obliviousness. But, believe it or not, they’re worth listening to, often outmatching all contenders for inventiveness and originality. This book profiles dozens of outsider musicians, both prominent and obscure, and presents their strange life stories along with photographs, interviews, cartoons, and discographies. Irwin Chusid is a record producer, radio personality, journalist, and music historian. He hosts the Incorrect Music Hour on WFMU; he has produced dozens of records and concerts; and he has written for The New York Times, Pulse, New York Press, and many other publications. $18.95 (CAN $20.95) ISBN 978-1-55652-372-4 51895 9 781556 523724 SONGS IN THE KEY OF Z Songs in the Key of Z THE CURIOUS UNIVERSE OF O U T S I D E R MUSIC ¥ Irwin Chusid Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chusid, Irwin. -

January 1995

Features PAUL WERTICO Pat Metheny's Paul Wertico is a bundle of contradictions: a highly exploratory drummer whose solo album is far from a chops-fest; a sophisticated accompanist who never took a lesson; a mainstream musician with avant-garde tendencies. Just who is this guy? Bill Milkowski 36 METAL DRUMMERS ROUND TABLE Away from the arenas and MTV cameras, today's top metal drummers have some serious issues to contend with—about the instrument they play and the business they're entangled in. Mike Portnoy, Deen Castronovo, Mark Zonder, Bobby Rock, Eric Singer, and John Tempesta cut to the chase. Matt Peiken 56 WHERE ARE THEY NOW? So you thought you'd never hear from the drummer in the Archies again—well, think again! Actually...we couldn't track him down.. .but we did get a hold of lots of your old faves— twenty-three of 'em, in fact. We think you might be surprised—and enlightened—by the stories they have to tell. Robyn Flans 76 Volume 19, Number 1 Cover Photo By Ebet Roberts Columns EDUCATION NEWS EQUIPMENT 100 ROCK 10 UPDATE 22 NEW AND PERSPECTIVES Black Sabbath's Bobby NOTABLE The Peart/Bozzio Rondinelli, Jay Schellen of Combination Challenge Sircle of Silence, BYRO B LEYTHAM Latin master Ignacio Berroa, and Jawbox's 102 ROCK 'N' Zach Barocas, plus News JAZZ CLINIC Hi-Hat Barks 133 INDUSTRY BY JOHN XEPOLEAS HAPPENINGS 1994 DCI World 104 LATIN Championship Results SYMPOSIUM BY LAUREN VOGELWEIS S The Soca BY RICH RYCHEL DEPARTMENTS 28 PRODUCT CLOSE-UP 106 UNDERSTANDING 4 EDITOR'S Yamaha Club RHYTHM OVERVIEW Custom Drumkit BY RICK VAN HORN Basic Reading: Part 2 BY HAL HOWLAND 6 READERS' 30 New Sabian Cymbals 110 STRICTLY PLATFORM BY RICK MATTINGLY TECHNIQUE 33 Evans Genera G2 The Sure-Fire 3:1 Cure 14 ASK A PRO Drumheads BY ED SHAUGHNESSY William Calhoun, BY RICK MATTINGLY David Garibaldi, 124 ARTIST ON and Blas Elias 114 SHOP TALK TRACK A Look At The GMS 16 IT'S Drum Company Jack DeJohnette BY ADAM BUDOFSKY BY MARK GRIFFITH QUESTIONABLE 126 CONCEPTS 120 CRITIQUE One Drummer's Psyche Vinnie Colaiuta and 112 SABIAN DREAM BY GLENN E. -

Program of the M

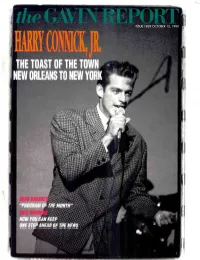

ISSUE 1828 OCTOBER 12, 1990 PROGRAM OF THE M www.americanradiohistory.com al In Loup Jenny Morris B e Loved " The Debut Single Produced by Andrew Farriss From The Album Shiver *It © 1990 WEA Records Ltd. www.americanradiohistory.com the GAVIN REPORT GOVh`i GIL ZE * Indicates Tie TOP 40 URBAN RAP MOST ADDED MOST ADDED MOST ADDED WHITNEY HOUSTON WHITNEY HOUSTON ISIS I'm Your Baby Tonight (Arista) I'm Your Baby Tonight (Arista) Rebel Soul BILLY JOEL GUY (Island /4th & Broadway) And It So Goes (Columbia) I Wanna Get With U (MCA) POOR RIGHTEOUS TEACHERS JON BON JOVI SURFACE (Profile) Miracles (Mercury) The First Time (Columbia) KING TEE (Capitol) RECORD TO WATCH RECORD TO LL COOL J WATCH RETAIL "The Boomin' System" 2 IN A ROOM HARRELL GRADY (Def Jam /Columbia) Wiggle It (Cutting /Charisma) Dorrt Turn Your Back On Me (RCA) Jv °tÍY. RADIO SYDNEY YOUNGBLOOD MONIE LOVE WILSON PHILLIPS I'd Rather Go Blind "Monie's In The Middle" Impulsive (SBK) (Arista) (Warner Bros.) COUNTRY JAZZ MOST ADDED MOST ADDED MOST ADDED WHITNEY HOUSTON RODNEY CROWELL LOU RAWLS I'm Your Baby Tonight (Arista) Now That We're Alone (Columbia) It's Supposed To Be Fun (Blue Note) WILSON PHILLIPS MARY CHAPIN CARPENTER RALPH MOORE Impulsive (SBK) You Win Again (Columbia) Furthermore (Landmark) SARA HICKMAN DWIGHT YOAKAM FATTBURGER I Couldn't Help Myself (Elektra) Turn It On, Turn It Up, Turn Me Loose (Reprise) Come & Get It (Enigma) RECORD TO WATCH RECORD TO WATCH RECORD TO WATCH THE NEVILLE BROTHERS featuring AARON NEVILLE ROB CROSBY RALPH MOORE Fearless (A &M) Love Will Bring -

Oingo Boingo

For the week of October 18-25« 1990 OINGO BOINGO HENRY ROLLINS HENRY AND JUNEg INSPIRAL CARPETS W l M , i l l k B Cover art by Todd Francis 2A Thursday, October 18,1990 Daily Nexus October 24 at 8 PM in the Main Theatre. The free program is presented as part of the Issues for the 1990s series ETHICS AND MORALITY IN THE UNITED STATES. Rastafari Woman The Independent! Films by Black Women series contin ues on Monday, October 22 with An Evening With Film Historian Pearl Bowser. A film archivist, Bowser will discuss the work of Black women filmmakers and will present the film Omega R isin g : Woman of Rastafari, a documentary by D. Elmina Davis. The film is both a history of the Rastafari movement and an exploration of the role of Rastafari women. Davis, herself a Rastafari member, addresses the myths and narrow stereotype of women in die movement. Interviews with Rastafari women in England and Jamaica are interwoven with contempo Turtle Island String Quartet photo: Ed Kashi rary images of Rastafari culture. The program is free and begins at 8 PM in the Isla Vista Theater. On Other Film Fronts Have you made it to any of the intriguing films in this A Jazz String Quartet quarter’s International Cinema series? These contem porary films really do offer you the chance to see what today’s best international filmmakers are producing. For example, in the Italian charmer A B oy F rom on the Loose C a la b ria , showing on Sunday, October 21 at 8 PM in Campbell Hall, a 13-year-old boy of peasant stock doesn’t let parental expectations get in the way of his leave of absence of the Monitor and set up the TISQ: A Musical Opportunity love of running.