DISH Network L.L.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Channel Guide 424 NFL Redzone HD

ADD TO YOUR PACKAGE for an additional fee A LA CARTE 124 NFL RedZone Channel Guide 424 NFL RedZone HD COLLEGE SPORTS PACK 23 SEC Network 127 Fox College Sports (Atlantic) 30 ESPNU 128 Fox College Sports (Pacific) 32 Outdoor Channel 129 Fox College Sports (Central) 33 Sportsman Channel PREMIUM CHANNELS 500 HBO 503 HBO Family HBO 501 HBO 2 504 HBO Comedy 502 HBO Signature 505 HBO Zone 550 Cinemax 554 Movie MAX 551 More MAX 555 Cinemax Latino Cinemax 552 Action MAX 556 5StarMAX 553 Thriller MAX 557 OuterMAX 560 SHOWTIME Family Zone 561 SHOWTIME 2 567 SHOWTIME 562 SHOWTIME BET Women 563 SHOWTIME 570 TMC Extreme Showtime 571 TMC Extra 564 SHOWTIME x 572 FLIX BET 565 SHOWTIME Next 566 SHOWTIME 581 STARZ 592 STARZ ENCORE 582 STARZ in Black Classic 583 STARZ Kids & 593 STARZ ENCORE Family Suspense Starz/ 584 STARZ Edge 594 STARZ ENCORE Encore 585 STARZ Cinema Black 586 STARZ Comedy 595 STARZ ENCORE 590 STARZ ENCORE Westerns 591 STARZ ENCORE 596 STARZ ENCORE Action Family AcenTek Video is not available in all areas. Programming is subject to change without notice. All channels not available to everyone. Additional charges may apply to commercial GRAND RAPIDS DMA PREMIUM HD CHANNELS customers for some of the available channels. For assistance 700 HBO HD 781 STARZ HD call Customer Service at 616.895.9911. 750 Cinemax HD 790 STARZ ENCORE HD Revised 8/30/21 760 Showtime HD 6568 Lake Michigan Drive | PO Box 509 | Allendale, MI 49401 AcenTek.net BASIC VIDEO Basic Video is available in Standard or High Definition. -

Exhibit 99.1

News Release Contact: Lucy Rutishauser, SVP Chief Financial Officer (410) 568-1500 SINCLAIR REPORTS SECOND QUARTER 2018 FINANCIAL RESULTS • INCREASES REVENUE AND OPERATING INCOME COMPARED TO PRIOR YEAR • REPORTS $0.27 DILUTED EARNINGS PER SHARE • DECLARES $0.18 QUARTERLY DIVIDEND PER SHARE BALTIMORE (August 8, 2018) - Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc. (Nasdaq: SBGI), the “Company” or “Sinclair,” today reported financial results for the three and six months ended June 30, 2018. CEO Comment: “Second quarter results came in well ahead of guidance in all key financial metrics, and we expect the second half of the year to continue to be robust, underlined by increasing distribution revenues and strong political advertising spend," commented Chris Ripley, President and Chief Executive Officer. "This year's mid-term elections are expected by many to have the most spending in U.S. history with broadcast television a primary beneficiary. In regards to the acquisition of Tribune Media Company, we are working with them to analyze approaches to the regulatory process that are in the best interest of our companies, employees and shareholders.” Three Months Ended June 30, 2018 Financial Results: • Total revenues increased 11.9% to $730.1 million versus $652.2 million in the prior year period. • Operating income was $131.6 million, including $6 million of one-time transaction costs, versus operating income of $118.8 million in the prior year period, which also included $6 million of one-time transaction costs. • Net income attributable to the Company was $28.0 million versus net income of $44.6 million in the prior year period, and includes $39 million in gross ticking fee costs related to the financing commitments for the Tribune acquisition. -

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

Sinclair Broadcast Group Closes on Acquisition of Barrington Stations

Contact: David Amy, EVP & CFO, Sinclair Lucy Rutishauser, VP & Treasurer, Sinclair (410) 568-1500 SINCLAIR BROADCAST GROUP CLOSES ON ACQUISITION OF BARRINGTON STATIONS BALTIMORE (November 25, 2013) -- Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc. (Nasdaq: SBGI) (the “Company” or “Sinclair”) announced today that it closed on its previously announced acquisition of 18 television stations owned by Barrington Broadcasting Group, LLC (“Barrington”) for $370.0 million and entered into agreements to operate or provide sales services to another six stations. The 24 stations are located in 15 markets and reach 3.4% of the U.S. TV households. The acquisition was funded through cash on hand. As previously discussed, due to FCC ownership conflict rules, Sinclair sold its station in Syracuse, NY, WSYT (FOX), and assigned its local marketing agreement (“LMA”) and purchase option on WNYS (MNT) in Syracuse, NY to Bristlecone Broadcasting. The Company also sold its station in Peoria, IL, WYZZ (FOX) to Cunningham Broadcasting Corporation (“CBC”). In addition, the license assets of three stations were purchased by CBC (WBSF in Flint, MI and WGTU/WGTQ in Traverse City/Cadillac, MI) and the license assets of two stations were purchase by Howard Stirk Holdings (WEYI in Flint, MI and WWMB in Myrtle Beach, SC) to which Sinclair will provide services pursuant to shared services and joint sales agreements. Following its acquisition by Sinclair, WSTM (NBC) in Syracuse, NY, will continue to provide services to WTVH (CBS), which is owned by Granite Broadcasting, and receive services on WHOI in Peoria, IL from Granite Broadcasting. Sinclair has, however, notified Granite Broadcasting that it does not intend to renew these agreements in these two markets when they expire in March of 2017. -

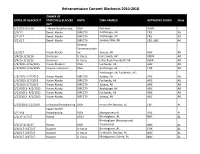

Retrans Blackouts 2010-2018

Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 OWNER OF DATES OF BLACKOUT STATION(S) BLACKED MVPD DMA NAME(S) NETWORKS DOWN State OUT 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH National WGN - 2/3/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV Juneau-Stika, AK CBS, NBC AK General CoMMunication 12/5/17 Vision Alaska Inc. Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Fort SMitH, AK KXUN AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Little Rock-Pine Bluff, AK KLRA AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Vision Alaska II DISH Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Coastal Television DISH AncHorage, AK FOX AK AncHorage, AK; Fairbanks, AK; 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV AncHorage, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/23/2018-2/2/2018 Lockwood Broadcasting DISH Huntsville-Decatur, AL CW AL SagaMoreHill 5/22/18 Broadcasting DISH MontgoMery AL ABC AL 1/1/17-1/7/17 Hearst AT&T BirMingHaM, AL NBC AL BirMingHaM (Anniston and 3/3/17-4/26/17 Hearst DISH Tuscaloosa) NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse BirMingHaM, AL FOX AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse Huntsville-Decatur, AL NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse MontgoMery-SelMa, AL NBC AL Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH -

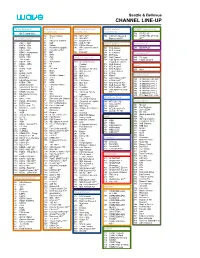

Channel Lineup

Seattle & Bellevue CHANNEL LINEUP TV On Demand* Expanded Content* Expanded Content* Digital Variety* STARZ* (continued) (continued) (continued) (continued) 1 On Demand Menu 716 STARZ HD** 50 Travel Channel 774 MTV HD** 791 Hallmark Movies & 720 STARZ Kids & Family Local Broadcast* 51 TLC 775 VH1 HD** Mysteries HD** HD** 52 Discovery Channel 777 Oxygen HD** 2 CBUT CBC 53 A&E 778 AXS TV HD** Digital Sports* MOVIEPLEX* 3 KWPX ION 54 History 779 HDNet Movies** 4 KOMO ABC 55 National Geographic 782 NBC Sports Network 501 FCS Atlantic 450 MOVIEPLEX 5 KING NBC 56 Comedy Central HD** 502 FCS Central 6 KONG Independent 57 BET 784 FXX HD** 503 FCS Pacific International* 7 KIRO CBS 58 Spike 505 ESPNews 8 KCTS PBS 59 Syfy Digital Favorites* 507 Golf Channel 335 TV Japan 9 TV Listings 60 TBS 508 CBS Sports Network 339 Filipino Channel 10 KSTW CW 62 Nickelodeon 200 American Heroes Expanded Content 11 KZJO JOEtv 63 FX Channel 511 MLB Network Here!* 12 HSN 64 E! 201 Science 513 NFL Network 65 TV Land 13 KCPQ FOX 203 Destination America 514 NFL RedZone 460 Here! 14 QVC 66 Bravo 205 BBC America 515 Tennis Channel 15 KVOS MeTV 67 TCM 206 MTV2 516 ESPNU 17 EVINE Live 68 Weather Channel 207 BET Jams 517 HRTV PayPerView* 18 KCTS Plus 69 TruTV 208 Tr3s 738 Golf Channel HD** 800 IN DEMAND HD PPV 19 Educational Access 70 GSN 209 CMT Music 743 ESPNU HD** 801 IN DEMAND PPV 1 20 KTBW TBN 71 OWN 210 BET Soul 749 NFL Network HD** 802 IN DEMAND PPV 2 21 Seattle Channel 72 Cooking Channel 211 Nick Jr. -

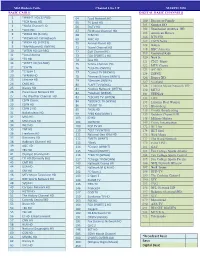

2020 March Channel Line up with Pricing Color

B is Mid-Hudson Cable Channel Line UP MARCH 2020 BASIC CABLE DIGITAL BASIC CHANNELS 2 *WMHT HD (17 PBS) 64 Food Network HD 100 Discovery Family 3 *FOX News HD 65 TV Land HD 101 Science HD 4 *NASA Channel HD 66 TruTV HD 102 Destination America HD 5 *QVC HD 67 FX Movie Channe l HD 105 American Heroes 6 *WRGB HD (6-CBS) 68 TCM HD 106 BTN HD 7 *WCWN HD CW Network 69 AMC HD 107 ESPN News 8 *WXXA HD (FOX23) 70 Animal Planet HD 108 Babytv 9 *My4AlbanyHD (WNYA) 71 Travel Channel HD 118 BBC America 10 *WTEN HD (10-ABC) 72 Golf Channel HD 119 Universal Kids 11 *Local Access 73 FOX SPORTS 1 HD 12 *FX HD 120 Nick Jr. 74 fuse HD 121 CMT Music 13 *WNYT HD (13-NBC) 75 Tennis Channel HD 122 MTV Classic 17 *EWTN 76 *LIGHTtv (WNYA) 123 IFC HD 19 *C-Span 1 77 *Comet TV (WCWN) 124 ESPNU 20 *WRNN HD 78 *Heroes & Icons (WNYT) 126 Disney XD 23 Lifetime HD 79 *Decades (WNYA) 127 Viceland 24 CNBC HD 80 *LAFF TV (WXXA) 128 Lifetime Movie Network HD 25 Disney HD 81 *Justice Network (WTEN) 130 MTV2 26 Paramount Network HD 82 *Stadium (WRGB) 131 TEENick 27 The Weather Channel HD 83 *ESCAPE TV (WTEN) 132 LIFE 28 ESPN Classic 84 *BOUNCE TV (WXXA) 133 Lifetime Real Women 29 ESPN HD 86 *START TV 135 Bloomberg 30 ESPN 2 HD 95 *HSN HD 138 Trinity Broadcasting 31 Nickelodeon HD 99 *PBS Kids(WMHT) 139 Outdoor Channel HD 32 MSG HD 103 ID HD 148 Military History 33 MSG PLUS HD 104 OWN HD 149 Crime Investigation 34 WE! HD 109 POP TV HD 172 BET her 35 TNT HD 110 *GET TV (WTEN) 174 BET Soul 36 Freeform HD 111 National Geo Wild HD 175 Nick Music 37 Discovery HD 112 *METV (WNYT) -

Download Streaming TV Lineup

TiVo Logo Lockup | 4C Blue RCN STREAMING TV Boston Channel Lineup RCN SIGNATURE CH CH CH CH CH CH 1 RCN On Demand 111 FX HD 306 HLN HD 866 Music Choice Metal 1126-1128 Milton PEG 1144-1146 Stoneham PEG 2 WGBH HD (PBS) 112 SYFY HD 310 CNBC HD 867 Music Choice Alternative 1129-1131 Natick PEG 1147-1149 Wakefield PEG 4 WBZ 4 HD (CBS) 115 E! HD 311 MSNBC HD 868 Music Choice Adult Alternative 1132-1134 Needham PEG 1150-1152 Waltham PEG 5 WCVB HD (ABC) 116 TRU TV HD 312 NBCLX 869 Music Choice Rock Hits 1135-1137 Newton PEG 1153-1155 Woburn PEG 6 WFXT HD (FOX) 117 COMEDY CENTRAL HD 315 FOX NEWS HD 870 Music Choice Classic Rock 1138-1140 Revere PEG 1156-1158 Watertown PEG 7 WHDH HD (NBC) 118 JUSTICE CENTRAL HD 316 FOX BUSN NEWS HD 871 Music Choice Soft Rock 1141-1143 Somerville PEG 1159-1161 Peabody PEG 8 WLVI HD (CW) 120 ANIMAL PLANET HD 318 NECN HD 872 Music Choice Love Songs 9 WGBH CREATE 128 GSN HD 320 WEATHER CH HD-MA 873 Music Choice Pop Hits 10 WBTS HD (NBC) 140 REELZ HD 321 Accuweather 874 Music Choice Party Favorites 11 WSBK MyTV 141 FXM HD 330 NASA 875 Music Choice Teen Beats RCN PREMIERE 12 WBPX HD (ION) 142 AMC HD 333 TRAVEL HD 876 Music Choice Kidz Only 14 WGBX (PBS 44) 143 TCM HD 335 DISCOVERY HD 877 Music Choice Toddler Tunes CH CH 16 WNEU HD (TELEMUNDO 60) 158 IFC HD 336 OWN HD 878 Music Choice Y2K Movies & Entertainment 249 BOOMERANG 17 WUNI HD (UNIVISION) 159 SUNDANCE TV HD 337 ID HD 879 Music Choice 90’s 103 BET HER 252 DISNEY XD HD 18 WWJE Justice 160 MTV HD 340 HISTORY HD 880 Music Choice 80’s 113 OLYMPIC CH 255 DISCOVERY -

Ciel-2 Satellite Now Operational

CIEL-2 SATELLITE NOW OPERATIONAL Satellite Completes all Testing and Begins Commercial Service at 129 Degrees West February 5th, 2009 – Ottawa, Canada – The Ciel Satellite Group today announced that its first communications satellite, Ciel-2, has completed all in-orbit testing and has now entered commercial service at the 129 degrees West Longitude orbital position. The new satellite was launched last December 10 from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, and will be providing high-definition (HD) television services to the North American market, primarily for anchor customer DISH Network Corporation. “We are very pleased that Ciel-2 has successfully completed all of its initial testing, and are excited about its entry into commercial operations,” said Brian Neill, Executive Chairman of Ciel. “The support of many parties, particularly our shareholders and Industry Canada, has been central to our success, and we look forward to a bright future of serving customers for many years to come throughout North America.” About Ciel-2 Built by Thales Alenia Space, Ciel-2 is the largest Spacebus class spacecraft ever built, weighing 5,592 kg at launch; Ciel-2 is expected to operate for at least 15 years. The new BSS spacecraft is capable of serving all regions of Canada visible from 129 degrees West, as well as the larger North American market. The Ciel Satellite Group was awarded the license for 129 degrees West by Industry Canada in October 2004. Ciel-2 will be operated from the new Satellite Operations Centre at SED Systems located in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada. The Ciel-2 satellite is designed to provide 10.6 kilowatts of power to the communications payload at end of life, which consists of 32 Ku-band transponders. -

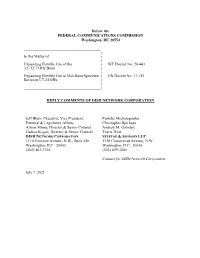

In the Matter of ) ) Expanding Flexible Use of the ) WT Docket No

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554 _______________________________________ ) In the Matter of ) ) Expanding Flexible Use of the ) WT Docket No. 20-443 12.-12.7 GHz Band ) ) Expanding Flexible Use in Mid-Band Spectrum ) GN Docket No. 17-183 Between 3.7-24 GHz ) ) ) REPLY COMMENTS OF DISH NETWORK CORPORATION Jeff Blum, Executive Vice President, Pantelis Michalopoulos External & Legislative Affairs Christopher Bjornson Alison Minea, Director & Senior Counsel Andrew M. Golodny Hadass Kogan, Director & Senior Counsel Travis West DISH NETWORK CORPORATION STEPTOE & JOHNSON LLP 1110 Vermont Avenue, N.W., Suite 450 1330 Connecticut Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20005 Washington, D.C. 20036 (202) 463-3702 (202) 429-3000 Counsel for DISH Network Corporation July 7, 2021 Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY .............................................................................. 1 II. A BROAD SPECTRUM OF PUBLIC INTEREST AND BUSINESS ENTITIES, INCLUDING DISINTERESTED ENTITIES, SUPPORTS 5G IN THE BAND ............. 7 III. THE PROPOSAL’S FEW OPPONENTS DO NOT CLOSE THE DOOR TO 5G IN THE BAND .................................................................................................................. 9 IV. SHARING IS EMINENTLY FEASIBLE ....................................................................... 10 A. Sharing Is Possible Between Higher-Power Two-Way Terrestrial Services and DBS ............................................................................................................... 10 -

Nexstar Media Group Stations(1)

Nexstar Media Group Stations(1) Full Full Full Market Power Primary Market Power Primary Market Power Primary Rank Market Stations Affiliation Rank Market Stations Affiliation Rank Market Stations Affiliation 2 Los Angeles, CA KTLA The CW 57 Mobile, AL WKRG CBS 111 Springfield, MA WWLP NBC 3 Chicago, IL WGN Independent WFNA The CW 112 Lansing, MI WLAJ ABC 4 Philadelphia, PA WPHL MNTV 59 Albany, NY WTEN ABC WLNS CBS 5 Dallas, TX KDAF The CW WXXA FOX 113 Sioux Falls, SD KELO CBS 6 San Francisco, CA KRON MNTV 60 Wilkes Barre, PA WBRE NBC KDLO CBS 7 DC/Hagerstown, WDVM(2) Independent WYOU CBS KPLO CBS MD WDCW The CW 61 Knoxville, TN WATE ABC 114 Tyler-Longview, TX KETK NBC 8 Houston, TX KIAH The CW 62 Little Rock, AR KARK NBC KFXK FOX 12 Tampa, FL WFLA NBC KARZ MNTV 115 Youngstown, OH WYTV ABC WTTA MNTV KLRT FOX WKBN CBS 13 Seattle, WA KCPQ(3) FOX KASN The CW 120 Peoria, IL WMBD CBS KZJO MNTV 63 Dayton, OH WDTN NBC WYZZ FOX 17 Denver, CO KDVR FOX WBDT The CW 123 Lafayette, LA KLFY CBS KWGN The CW 66 Honolulu, HI KHON FOX 125 Bakersfield, CA KGET NBC KFCT FOX KHAW FOX 129 La Crosse, WI WLAX FOX 19 Cleveland, OH WJW FOX KAII FOX WEUX FOX 20 Sacramento, CA KTXL FOX KGMD MNTV 130 Columbus, GA WRBL CBS 22 Portland, OR KOIN CBS KGMV MNTV 132 Amarillo, TX KAMR NBC KRCW The CW KHII MNTV KCIT FOX 23 St. Louis, MO KPLR The CW 67 Green Bay, WI WFRV CBS 138 Rockford, IL WQRF FOX KTVI FOX 68 Des Moines, IA WHO NBC WTVO ABC 25 Indianapolis, IN WTTV CBS 69 Roanoke, VA WFXR FOX 140 Monroe, AR KARD FOX WTTK CBS WWCW The CW WXIN FOX KTVE NBC 72 Wichita, KS -

SPECTRUM TV PACKAGES Hillsborough, Pinellas, Pasco & Hernando Counties |

SPECTRUM TV PACKAGES Hillsborough, Pinellas, Pasco & Hernando Counties | Investigation Discovery WFTS - ABC HD GEM Shopping Network Tennis Channel 87 1011 1331 804 TV PACKAGES SEC Extra HD WMOR - IND HD GEM Shopping Network HD FOX Sports 2 88 1012 1331 806 SundanceTV WTVT - FOX HD EWTN CBS Sports Network 89 1013 1340 807 Travel Channel WRMD - Telemundo HD AMC MLB Network SPECTRUM SELECT 90 1014 1355 815 WTAM - Azteca America WVEA - Univisión HD SundanceTV Olympic Channel 93 1015 1356 816 (Includes Spectrum TV Basic Community Programming WEDU - PBS Encore HD IFC NFL Network 95 1016 1363 825 and the following services) ACC Network HD WXPX - ION HD Hallmark Mov. & Myst. ESPN Deportes 99 1017 1374 914 WCLF - CTN HSN WGN America IFC FOX Deportes 2 101 1018 1384 915 WEDU - PBS HSN HD Nickelodeon Hallmark Mov. & Myst. NBC Universo 3 101 1102 1385 929 WTOG - The CW Disney Channel Disney Channel FX Movie Channel El Rey Network 4 105 1105 1389 940 WFTT - UniMás Travel Channel SonLife WVEA - Univisión HD TUDN 5 106 1116 1901 942 WTTA - MyTV EWTN Daystar WFTT - UniMás HD Disney Junior 6 111 1117 1903 1106 WFLA - NBC FOX Sports 1 INSP Galavisión Disney XD 8 112 1119 1917 1107 Bay News 9 IFC Freeform WRMD - Telemundo HD Universal Kids 9 113 1121 1918 1109 WTSP - CBS SundanceTV Hallmark Channel Nick Jr. 10 117 1122 1110 WFTS - ABC FX Upliftv HD BYUtv 11 119 1123 SPECTRUM TV BRONZE 1118 WMOR - IND FXX ESPN ESPNEWS 12 120 1127 1129 WTVT - FOX Bloomberg Television ESPN2 (Includes Spectrum TV Select ESPNU 13 127 1128 and the following channels) 1131 C-SPAN TBN FS Sun ESPN Deportes 14 131 1148 1132 WVEA - Univisión Investigation Discovery FS Florida FOX Sports 2 15 135 1149 1136 WXPX - ION FOX Business Network SEC Network Digi Tier 1 CBS Sports Network 17 149 1150 1137 WGN America Galavisión NBC Sports Network LMN NBA TV 18 155 1152 50 1140 WRMD - Telemundo SHOPHQ FOX Sports 1 TCM MLB Network 19 160 1153 53 1141 TBS HSN2 HD SEC Extra HD Golf Channel NFL Network 23 161 1191 67 1145 OWN QVC2 - HD Spectrum Sports Networ.