Arxiv:1609.02949V1 [Math.AT] 9 Sep 2016 1 Lecture 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Circuit Diameter Conjecture

On the Circuit Diameter Conjecture Steffen Borgwardt1, Tamon Stephen2, and Timothy Yusun2 1 University of Colorado Denver [email protected] 2 Simon Fraser University {tamon,tyusun}@sfu.ca Abstract. From the point of view of optimization, a critical issue is relating the combina- torial diameter of a polyhedron to its number of facets f and dimension d. In the seminal paper of Klee and Walkup [KW67], the Hirsch conjecture of an upper bound of f − d was shown to be equivalent to several seemingly simpler statements, and was disproved for unbounded polyhedra through the construction of a particular 4-dimensional polyhedron U4 with 8 facets. The Hirsch bound for bounded polyhedra was only recently disproved by Santos [San12]. We consider analogous properties for a variant of the combinatorial diameter called the circuit diameter. In this variant, the walks are built from the circuit directions of the poly- hedron, which are the minimal non-trivial solutions to the system defining the polyhedron. We are able to prove that circuit variants of the so-called non-revisiting conjecture and d-step conjecture both imply the circuit analogue of the Hirsch conjecture. For the equiva- lences in [KW67], the wedge construction was a fundamental proof technique. We exhibit why it is not available in the circuit setting, and what are the implications of losing it as a tool. Further, we show the circuit analogue of the non-revisiting conjecture implies a linear bound on the circuit diameter of all unbounded polyhedra – in contrast to what is known for the combinatorial diameter. Finally, we give two proofs of a circuit version of the 4-step conjecture. -

A General Geometric Construction of Coordinates in a Convex Simplicial Polytope

A general geometric construction of coordinates in a convex simplicial polytope ∗ Tao Ju a, Peter Liepa b Joe Warren c aWashington University, St. Louis, USA bAutodesk, Toronto, Canada cRice University, Houston, USA Abstract Barycentric coordinates are a fundamental concept in computer graphics and ge- ometric modeling. We extend the geometric construction of Floater’s mean value coordinates [8,11] to a general form that is capable of constructing a family of coor- dinates in a convex 2D polygon, 3D triangular polyhedron, or a higher-dimensional simplicial polytope. This family unifies previously known coordinates, including Wachspress coordinates, mean value coordinates and discrete harmonic coordinates, in a simple geometric framework. Using the construction, we are able to create a new set of coordinates in 3D and higher dimensions and study its relation with known coordinates. We show that our general construction is complete, that is, the resulting family includes all possible coordinates in any convex simplicial polytope. Key words: Barycentric coordinates, convex simplicial polytopes 1 Introduction In computer graphics and geometric modelling, we often wish to express a point x as an affine combination of a given point set vΣ = {v1,...,vi,...}, x = bivi, where bi =1. (1) i∈Σ i∈Σ Here bΣ = {b1,...,bi,...} are called the coordinates of x with respect to vΣ (we shall use subscript Σ hereafter to denote a set). In particular, bΣ are called barycentric coordinates if they are non-negative. ∗ [email protected] Preprint submitted to Elsevier Science 3 December 2006 v1 v1 x x v4 v2 v2 v3 v3 (a) (b) Fig. -

7 LATTICE POINTS and LATTICE POLYTOPES Alexander Barvinok

7 LATTICE POINTS AND LATTICE POLYTOPES Alexander Barvinok INTRODUCTION Lattice polytopes arise naturally in algebraic geometry, analysis, combinatorics, computer science, number theory, optimization, probability and representation the- ory. They possess a rich structure arising from the interaction of algebraic, convex, analytic, and combinatorial properties. In this chapter, we concentrate on the the- ory of lattice polytopes and only sketch their numerous applications. We briefly discuss their role in optimization and polyhedral combinatorics (Section 7.1). In Section 7.2 we discuss the decision problem, the problem of finding whether a given polytope contains a lattice point. In Section 7.3 we address the counting problem, the problem of counting all lattice points in a given polytope. The asymptotic problem (Section 7.4) explores the behavior of the number of lattice points in a varying polytope (for example, if a dilation is applied to the polytope). Finally, in Section 7.5 we discuss problems with quantifiers. These problems are natural generalizations of the decision and counting problems. Whenever appropriate we address algorithmic issues. For general references in the area of computational complexity/algorithms see [AB09]. We summarize the computational complexity status of our problems in Table 7.0.1. TABLE 7.0.1 Computational complexity of basic problems. PROBLEM NAME BOUNDED DIMENSION UNBOUNDED DIMENSION Decision problem polynomial NP-hard Counting problem polynomial #P-hard Asymptotic problem polynomial #P-hard∗ Problems with quantifiers unknown; polynomial for ∀∃ ∗∗ NP-hard ∗ in bounded codimension, reduces polynomially to volume computation ∗∗ with no quantifier alternation, polynomial time 7.1 INTEGRAL POLYTOPES IN POLYHEDRAL COMBINATORICS We describe some combinatorial and computational properties of integral polytopes. -

Fitting Tractable Convex Sets to Support Function Evaluations

Fitting Tractable Convex Sets to Support Function Evaluations Yong Sheng Sohy and Venkat Chandrasekaranz ∗ y Institute of High Performance Computing 1 Fusionopolis Way #16-16 Connexis Singapore 138632 z Department of Computing and Mathematical Sciences Department of Electrical Engineering California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA 91125, USA March 11, 2019 Abstract The geometric problem of estimating an unknown compact convex set from evaluations of its support function arises in a range of scientific and engineering applications. Traditional ap- proaches typically rely on estimators that minimize the error over all possible compact convex sets; in particular, these methods do not allow for the incorporation of prior structural informa- tion about the underlying set and the resulting estimates become increasingly more complicated to describe as the number of measurements available grows. We address both of these short- comings by describing a framework for estimating tractably specified convex sets from support function evaluations. Building on the literature in convex optimization, our approach is based on estimators that minimize the error over structured families of convex sets that are specified as linear images of concisely described sets { such as the simplex or the free spectrahedron { in a higher-dimensional space that is not much larger than the ambient space. Convex sets parametrized in this manner are significant from a computational perspective as one can opti- mize linear functionals over such sets efficiently; they serve a different purpose in the inferential context of the present paper, namely, that of incorporating regularization in the reconstruction while still offering considerable expressive power. We provide a geometric characterization of the asymptotic behavior of our estimators, and our analysis relies on the property that certain sets which admit semialgebraic descriptions are Vapnik-Chervonenkis (VC) classes. -

Polytopes with Special Simplices 3

POLYTOPES WITH SPECIAL SIMPLICES TIMO DE WOLFF Abstract. For a polytope P a simplex Σ with vertex set V(Σ) is called a special simplex if every facet of P contains all but exactly one vertex of Σ. For such polytopes P with face complex F(P ) containing a special simplex the sub- complex F(P )\V(Σ) of all faces not containing vertices of Σ is the boundary of a polytope Q — the basis polytope of P . If additionally the dimension of the affine basis space of F(P )\V(Σ) equals dim(Q), we call P meek; otherwise we call P wild. We give a full combinatorial classification and techniques for geometric construction of the class of meek polytopes with special simplices. We show that every wild polytope P ′ with special simplex can be constructed out of a particular meek one P by intersecting P with particular hyperplanes. It is non–trivial to find all these hyperplanes for an arbitrary basis polytope; we give an exact description for 2–basis polytopes. Furthermore we show that the f–vector of each wild polytope with special simplex is componentwise bounded above by the f–vector of a particular meek one which can be computed explicitly. Finally, we discuss the n–cube as a non–trivial example of a wild polytope with special simplex and prove that its basis polytope is the zonotope given by the Minkowski sum of the (n − 1)–cube and vector (1,..., 1). Polytopes with special simplex have applications on Ehrhart theory, toric rings and were just used by Francisco Santos to construct a counter–example disproving the Hirsch conjecture. -

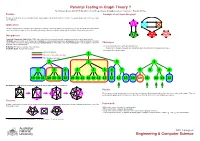

Parental Testing in Graph Theory?

Parental Testing in Graph Theory ? By S Narjess Afzaly,∗ ANU CSIT Algorithm & Data Group, [email protected]. Supervisor: Brendan McKay.∗ Problem A sample of an irreducible graph To make a complete list of non-isomorphic simple quartic graphs with the given number of vertices. In a quartic graph, each vertex has exactly four neighbours. Applications Finding counterexamples, verifying some conjectures or refining some proofs whether in graph theory or in any other field where the problem can be modelled as a graph such as: chemistry, web mining, national security, the railway map, the electrical circuit and neural science. Our approach Canonical Construction Path (McKay 1998): A general method to recursively generate combinatorial objects in which larger objects, (Children), are constructed out of smaller ones, (Parents), by some well-defined operation, (extension), and avoiding constructing isomorphic copies at each construction step by defining a unique genuine parent for each graph. Hence a generated graph is only accepted if it has been Challenges extended from its genuine parent. • To avoid isomorphic copies when generating the list: Reduction: The inverse operation of the extension. Irreducible graph: A graph with no parent. The definition of the genuine parent can substantially affect the efficiency of the generation process. • Generating all irreducible graphs. Genuine parent 1 Has an isomorphic sibling Not genuine parent 2 2 3 4 5 5 6 5 5 6 6 7 5 8 9 6 10 10 11 10 10 11 12 10 10 11 10 10 11 12 12 12 13 10 10 11 10 13 12 Our Reduction: Deleting a vertex and adding two extra disjoint edges between its neighbours. -

15 BASIC PROPERTIES of CONVEX POLYTOPES Martin Henk, J¨Urgenrichter-Gebert, and G¨Unterm

15 BASIC PROPERTIES OF CONVEX POLYTOPES Martin Henk, J¨urgenRichter-Gebert, and G¨unterM. Ziegler INTRODUCTION Convex polytopes are fundamental geometric objects that have been investigated since antiquity. The beauty of their theory is nowadays complemented by their im- portance for many other mathematical subjects, ranging from integration theory, algebraic topology, and algebraic geometry to linear and combinatorial optimiza- tion. In this chapter we try to give a short introduction, provide a sketch of \what polytopes look like" and \how they behave," with many explicit examples, and briefly state some main results (where further details are given in subsequent chap- ters of this Handbook). We concentrate on two main topics: • Combinatorial properties: faces (vertices, edges, . , facets) of polytopes and their relations, with special treatments of the classes of low-dimensional poly- topes and of polytopes \with few vertices;" • Geometric properties: volume and surface area, mixed volumes, and quer- massintegrals, including explicit formulas for the cases of the regular simplices, cubes, and cross-polytopes. We refer to Gr¨unbaum [Gr¨u67]for a comprehensive view of polytope theory, and to Ziegler [Zie95] respectively to Gruber [Gru07] and Schneider [Sch14] for detailed treatments of the combinatorial and of the convex geometric aspects of polytope theory. 15.1 COMBINATORIAL STRUCTURE GLOSSARY d V-polytope: The convex hull of a finite set X = fx1; : : : ; xng of points in R , n n X i X P = conv(X) := λix λ1; : : : ; λn ≥ 0; λi = 1 : i=1 i=1 H-polytope: The solution set of a finite system of linear inequalities, d T P = P (A; b) := x 2 R j ai x ≤ bi for 1 ≤ i ≤ m ; with the extra condition that the set of solutions is bounded, that is, such that m×d there is a constant N such that jjxjj ≤ N holds for all x 2 P . -

Fast Generation of Planar Graphs (Expanded Version)

Fast generation of planar graphs (expanded version) Gunnar Brinkmann∗ Brendan D. McKay† Department of Applied Mathematics Department of Computer Science and Computer Science Australian National University Ghent University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia B-9000 Ghent, Belgium [email protected] [email protected] Abstract The program plantri is the fastest isomorph-free generator of many classes of planar graphs, including triangulations, quadrangulations, and convex polytopes. Many applications in the natural sciences as well as in mathematics have appeared. This paper describes plantri’s principles of operation, the basis for its efficiency, and the recursive algorithms behind many of its capabilities. In addition, we give many counts of isomorphism classes of planar graphs compiled using plantri. These include triangulations, quadrangulations, convex polytopes, several classes of cubic and quartic graphs, and triangulations of disks. This paper is an expanded version of the paper “Fast generation of planar graphs” to appeared in MATCH. The difference is that this version has substantially more tables. 1 Introduction The program plantri can rapidly generate many classes of graphs embedded in the plane. Since it was first made available, plantri has been used as a tool for research of many types. We give only a partial list, beginning with masters theses [37, 40] and PhD theses [32, 42]. Applications have appeared in chemistry [8, 21, 28, 39, 44], in crystallography [19], in physics [25], and in various areas of mathematics [1, 2, 7, 20, 22, 24, 41]. ∗Research supported in part by the Australian National University. †Research supported by the Australian Research Council. 1 The purpose of this paper is to describe the facilities of plantri and to explain in general terms the method of operation. -

ADDENDUM the Following Remarks Were Added in Proof (November 1966). Page 67. an Easy Modification of Exercise 4.8.25 Establishes

ADDENDUM The following remarks were added in proof (November 1966). Page 67. An easy modification of exercise 4.8.25 establishes the follow ing result of Wagner [I]: Every simplicial k-"complex" with at most 2 k ~ vertices has a representation in R + 1 such that all the "simplices" are geometric (rectilinear) simplices. Page 93. J. H. Conway (private communication) has established the validity of the conjecture mentioned in the second footnote. Page 126. For d = 2, the theorem of Derry [2] given in exercise 7.3.4 was found earlier by Bilinski [I]. Page 183. M. A. Perles (private communication) recently obtained an affirmative solution to Klee's problem mentioned at the end of section 10.1. Page 204. Regarding the question whether a(~) = 3 implies b(~) ~ 4, it should be noted that if one starts from a topological cell complex ~ with a(~) = 3 it is possible that ~ is not a complex (in our sense) at all (see exercise 11.1.7). On the other hand, G. Wegner pointed out (in a private communication to the author) that the 2-complex ~ discussed in the proof of theorem 11.1 .7 indeed satisfies b(~) = 4. Page 216. Halin's [1] result (theorem 11.3.3) has recently been genera lized by H. A. lung to all complete d-partite graphs. (Halin's result deals with the graph of the d-octahedron, i.e. the d-partite graph in which each class of nodes contains precisely two nodes.) The existence of the numbers n(k) follows from a recent result of Mader [1] ; Mader's result shows that n(k) ~ k.2(~) . -

![Math.CO] 14 May 2002 in Npriua,Tecne Ulof Hull Convex Descrip the Simple Particular, Similarly in No Tion](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8229/math-co-14-may-2002-in-npriua-tecne-ulof-hull-convex-descrip-the-simple-particular-similarly-in-no-tion-1288229.webp)

Math.CO] 14 May 2002 in Npriua,Tecne Ulof Hull Convex Descrip the Simple Particular, Similarly in No Tion

Fat 4-polytopes and fatter 3-spheres 1, 2, † 3, ‡ David Eppstein, ∗ Greg Kuperberg, and G¨unter M. Ziegler 1Department of Information and Computer Science, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697 2Department of Mathematics, University of California, Davis, CA 95616 3Institut f¨ur Mathematik, MA 6-2, Technische Universit¨at Berlin, D-10623 Berlin, Germany φ We introduce the fatness parameter of a 4-dimensional polytope P, defined as (P)=( f1 + f2)/( f0 + f3). It arises in an important open problem in 4-dimensional combinatorial geometry: Is the fatness of convex 4- polytopes bounded? We describe and analyze a hyperbolic geometry construction that produces 4-polytopes with fatness φ(P) > 5.048, as well as the first infinite family of 2-simple, 2-simplicial 4-polytopes. Moreover, using a construction via finite covering spaces of surfaces, we show that fatness is not bounded for the more general class of strongly regular CW decompositions of the 3-sphere. 1. INTRODUCTION Only the two extreme cases of simplicial and of simple 4- polytopes (or 3-spheres) are well-understood. Their f -vectors F correspond to faces of the convex hull of F , defined by the The characterization of the set 3 of f -vectors of convex 4 valid inequalities f 2 f and f 2 f , and the g-Theorem, 3-dimensional polytopes (from 1906, due to Steinitz [28]) is 2 ≥ 3 1 ≥ 0 well-known and explicit, with a simple proof: An integer vec- proved for 4-polytopes by Barnette [1] and for 3-spheres by Walkup [34], provides complete characterizations of their f - tor ( f0, f1, f2) is the f -vector of a 3-polytope if and only if it satisfies vectors. -

Separators of Simple Polytopes

Fachbereich Mathematik und Informatik der Freien Universit¨atBerlin Separators of simple polytopes A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Natural Sciences to the Department of Department of Mathematics and Computer Science by Lauri Loiskekoski Berlin 2017 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. G¨unter M. Ziegler Second Examiner: Prof. Dr. Volker Kaibel Date of defense: 21.12.2017 Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank my supervisor G¨unter M. Ziegler for introducing me to this fascinating topic and always having time to discuss. You always knew the right references and had good ideas what to look at. I would like to thank Hao Chen, Arnau Padrol and Raman Sanyal for help- ing me get started on research and and answering my questions on separators and polytopes. I would like to thank my friends and colleague at the villa, in particular Francesco Grande, Katy Beeler, Albert Haase, Tobias Friedl, Philip Brinkmann, Nevena Pali´c,Jean-Philippe Labb´e,Giulia Codenotti, Jorge Alberto Olarte, Hannah Sch¨aferSj¨oberg and Anna Maria Hartkopf. Thanks for navigating the bureaucracy go to Elke Pose. Thanks to Johanna Steinmeyer for the TikZ pictures. I wish to thank the Berlin Mathematical School for funding my research and European Research Council and Osaka University for funding my travels. Finally, I would like to thank my friends in Finland, especially the people of Rissittely for answering all the unconventional questions I have had about academia and life in general. iii iv Contents Acknowledgements . iii 1 Introduction 1 2 Graphs and Polytopes 3 2.1 Polytopes . -

Three Questions on Graphs of Polytopes

Three questions on graphs of polytopes Guillermo Pineda-Villavicencio Federation University Australia G. Pineda-Villavicencio (FedUni) Mar 18 1 / 30 Outline 1 A polytope as a combinatorial object 2 First question: Reconstruction of polytopes 3 Second question: Connectivity of cubical polytopes 4 Third question: Linkedness of cubical polytopes G. Pineda-Villavicencio (FedUni) Mar 18 2 / 30 A polytope as a combinatorial object 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 3 5 7 0 1 4 5 2 3 6 7 0 2 4 6 0 1 2 3 6 7 5 7 4 5 1 5 6 7 3 7 4 6 0 4 1 3 0 1 2 6 2 3 0 2 0 1 4 5 5 7 4 1 6 3 0 2 G. Pineda-Villavicencio (FedUni) Mar 18 3 / 30 Reconstruction of polytopes (Dolittle, Nevo, Ugon & Yost) The k-skeleton of a polytope is the set of all its faces of dimension ≤ k. k-skeleton reconstruction: Given the k-skeleton of a polytope, can the face lattice of the polytope be completed? 4 5 6 7 1 3 5 7 0 1 4 5 2 3 6 7 0 2 4 6 0 1 2 3 5 7 4 5 1 5 6 7 3 7 4 6 0 4 1 3 0 1 2 6 2 3 0 2 5 7 4 1 6 3 0 2 G. Pineda-Villavicencio (FedUni) Mar 18 4 / 30 For d ≥ 4 there are pairs of d-polytopes with isomorphic (d − 3)-skeleta: a bipyramid over a (d − 1)-simplex and, a pyramid over the (d − 1)-bipyramid over a (d − 2)-simplex.