In the Woonasquatucket River Watershed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Woonasquatucket: American Heritage River

The Woonasquatucket: An American Heritage River Page 1 of 1 Superfund Records Center SITE: C__i__=la ie BREAK: OTHER no _ Donate Now! 4^04-0 3 WOONASQUATUCKET RIVER WATERSHED COUNCIL Home About UsD About the Watershed • Events Projects D Get Involved • Links Things to Buy The Woonasquatucket: An American Heritage More About Us: River • Who We Are & What We Do • In The News 'Tonight, I announce that this year I will designate 10 American Heritage An American Heritage River Rivers, to help communities alongside them revitalize their waterfronts and clean up pollution in the rivers, proving once again that we can grow • Our Staff the economy as we protect the environment." - President Clinton's 1997 • Our Funders State ofthe Union Address • Our Board • Employment Opportunities On July 30,1998 President Clinton designated the Woonasquatucket River as an American Heritage River. The Woonasquatucket is partnered • Way sto Contact Us with the Blackstone River for the purposes of this program. Senator John H. Chafee nominated the Woonasquatucket and Blackstone Rivers for this designation. The proposal received immediate and strong support from Senator Jack Reed, Representative Weygand, Representative Kennedy, and Governor Almond, and residents ofthe 6 communities along the River, including Glocester, North Smithfield, Smithfield, Johnston, North Providence and Providence. The river was chosen in part because ofthe significant role it played in the Industrial Revolution. The Woonasquatucket was one ofthe first rivers to be dammed by mill-owners to insure a steady Undated photograph of Riverside Mills in Providence. supply of water year-round for their mills. In the last thirty years, The building in the foreground still exists. -

ATTENDANCE: A. Members Present

The Rhode Island Rivers Council c/o RI Water Resources Board One Capitol Hill Providence, RI 02908 www.ririvers.org [email protected] Minutes of RIRC Meeting Wednesday, June 12, 2019 Meeting – 4 pm DEM Office of Water Resources – Conference Room 280C 235 Promenade Street, Providence, RI ATTENDANCE: A. Members Present: Veronica Berounsky, Chair Alicia Eichinger, Vice Chair Charles Horbert Walter Galloway Rachel Calabro Ernie Panciera Eugenia Marks B. Guests in Attendance: Elise Torello, Wood-Pawcatuck Watershed Association Michael Zarum, Buckeye Brook Coalition Jennifer Paquet, RI DEM Douglas Stephens, Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council Michael Bradlee, Friends of the Moshassuck Julia Bancroft, Narragansett Bay Estuary Program Susan Kiernan, RI DEM John Zwarg, RI DEM Betsy Dake, RI DEM Arthur Plitt, Blackstone River Watershed Council – Friends of the Moshassuck Margherita Pryor, US EPA Chelsea Glinna, VHB Introductions: All attending board members and guests introduced themselves. Prior to the start of the RIRC Meeting, representatives were available from RI DEM to provide a presentation and give the Watershed Councils an update on things they are working on. Updates were provided on multiple topics as follows: RI Non-Point Source Management Plan: This is overseen by EPA, and is required by Section 319 of the Clean Water Act. The plan is consistent with the State’s “Water Quality 2035” plan Plan elements were described Water quality conditions (descriptive) Management Framework Rules Statewide Priorities Implementation It has a five-year planning horizon focused on RIDEM actions. Priorities include stormwater; OWTS, agriculture, road salt, turf management, pet waste, and “other” sources. Other acknowledged stressors include: wetland alterations; aquatic invasives, stream connectivity, water withdrawals, and climate change. -

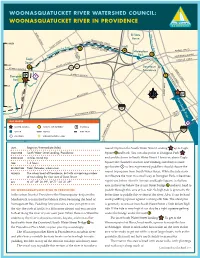

Woonasquatucket River in Providence95

WOONASQUATUCKET RIVER WATERSHED COUNCIL: Miles 1 SMITH STREET ORMS STREET WOONASQUATUCKET RIVER IN PROVIDENCE95 RIVER AVENUE RI State M o s House h PROMENADE STREET a s s 0 MILES u c k Mall KINSLEY AVENUE R VALLEY STREET River ket i uc 5 v at e ANGELL STREET ACORN 4 u r 1 sq STREET Waterplace na oo Park 3 W WATERMAN AVENUE Eagle ORIAL B .5 M O COLLEGE STREET ME U LE Square V A 0.25 R HARRIS AVENUE 6 Downtown D ATWELLS AVENUE 6 10 Providence BENEFIT STREET SOUTHMAIN WATER STREET ST ATWELLS AVENUE Donigian 7 2 Park 8 1A 25 DYER STREET 0. DEAN STREET 0.5 1 1 BROADWAY Providence River BIKE PATH 00 0.75 95 POST ROAD POINT WESTMINSTER STREET STREET Ninigret mAP LEGEND 9 Park 6 WATER ACCESS l POINTS OF INTEREST n P PARKING 195 n WATER ROADS BIKE PATH CAUTION CONSERVATION LAND u 10 n ELMWOOD AVE LEVEL Beginner/Intermediate (tides) round trip from the South Water Street Landing 1 up to Eagle START/END South Water Street Landing, Providence Square l6 and back. You can also put in at Donigian Park 8 RIVER MILES 4 miles round trip and paddle down to South Water Street. However, above Eagle TIME 1-2 hours Square the channel is narrow and winding and there is some 7 DESCRIPTION Tidal, flatwater, urban river quickwater u so less experienced paddlers should choose the round-trip option from South Water Street. While the tide starts SCENERY The urban heart of Providence, but with a surprising number of trees along the river west of Dean Street to influence the river in a small way at Donigian Park, it becomes 295 GPS N 41º 49’ 20.39”, W 71º 24’ 21.49” significant below Atwells Avenue and Eagle Square. -

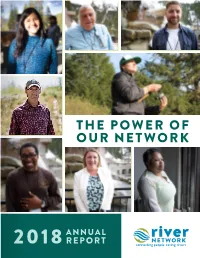

2018 Annual Report

THE POWER OF OUR NETWORK ANNUAL 2018 REPORT 2018 BY THE NUMBERS CELEBRATING 30 YEARS AND THE VIBRANT FUTURE OF OUR NETWORK 4,146 500 River Network was founded thirty years ago to strengthen local efforts to protect rivers. Over three INDIVIDUALS HOURS OF SUPPORT educated through decades our focus has remained remarkably consistent: We connect people to save rivers. That provided in simple tagline belies a tremendous amount of action to protect and restore waters across the country, particularly at the local level. Today this network is over 6,000 strong. 88 38 As backbone to this network, we educate and empower champions to effectively engage their EVENTS (River Rally, communities, influence decision makers, assert their opinion on policy change, and translate DIRECT strategies from our national network into local solutions for healthy rivers and clean water. Every webinars, and workshops) CONSULTATIONS day, thousands of these local champions are working across the U.S. Take a moment to meet our network and learn their stories. River Network began by helping river and watershed organizations expand protections for $80,000 13,385 pristine rivers. Since then our ambitions, leadership, and programs have evolved to align with our SCHOLARSHIPS granted to understanding of what rivers need to remain healthy, the challenges of a changing climate, and VOLUNTEERS attended significant shifts in the social, political, and economic context of water. While remaining committed to bolstering local groups and grassroots efforts, we now build Nicole Silk 141 24 coalitions across sectors—uniting NGOs, tribal nations, government agencies, and businesses RIVER RALLY PARTICIPANTS RIVER NETWORK to achieve bigger impacts. -

Activity Report for Our Conservation Partners

Activity Report for our Conservation Partners March – April 2009 Volume 1, Number 3 In This Issue Message From Pooh Vongkhamdy, State Conservationist • Upper Greetings from the Rhode Island Natural Resources Narragansett Bay Conservation Service State Office. During my first two months as Rhode Island State Conservationist, • Lower I worked extensively with staff to implement the Narragansett Bay 2008 Farm Bill programs. In addition, I spent a considerable amount of time meeting the various • Economics partners who pay an integral role in conservation • Biological efforts throughout Rhode Island. Sciences Highlights among the various activities include the following: • Earth Team NRCS worked with several partners to arrange a tour of Joslin Farm in Volunteer Scituate, RI where the general public was invited to learn about the project goals and progress to encourage wildlife habitat. The tour was a • Outreach And success with over 130 attendees and much positive feedback regarding Communications our efforts. • Performance Considerable progress was made on the Gooseneck Cove Wetland Update Reserve Program (WRP) project where NRCS provided approximately half of the funds needed to replace culverts and dam removal. It was • Engineering the first intentional dam removal in the State’s history. Services Several additional outreach events were completed including two • Resource recruiting events and a presentation at the unveiling of the Conservation & Woonasquatucket River Watershed River Panels at Providence Place Development where NRCS provided over $4.5 million in WHIP funds for the fish passage and river conservation efforts. • Soils Program NRCS staff worked diligently to roll out funding opportunities under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) for Emergency Watershed Protection-Floodplain Easements (EWP-FPE) where a total of 30 applications were received. -

RIRC Booklet Combined 2 27 2019

THE RHODE ISLAND RIVERS COUNCIL www.ririvers.org One Capitol Hill Providence, Rhode Island 02908 [email protected] RHODE ISLAND RIVERS COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP Veronica Berounsky, Chair Alicia Eichinger, Vice Chair Robert Billington Rachel Calabro Walter Galloway Charles Horbert Elise Torello INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERS Paul Gonsalves for Michael DiBiase, Department of Administration Eugenia Marks for Kathleen Crawley, Water Resources Board Ernie Panciera for Janet Coit, Department of Environmental Management Peder Schaefer for Mayor James Diossa, League of Cities and Towns Mike Walker for Stefan Pryor, Commerce Corporation Jeff Willis for Grover Fugate, Coastal Resource Management Council ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Photographs in this publication provided by: Rhode Island Rivers Council Elise Torello, cover photograph, Upper Wood River Charles Biddle, "Children Planting, Middlebridge", pg. 1 Booklet compilation and design services provided by Liz Garofalo THANK YOU This booklet was made possible by a RI legislative grant sponsored by Representatives: Carol Hagan McEntee, (D-District 33, South Kingstown/Narragansett) Robert E. Craven, Sr., (D-District 32, North Kingstown) 2 RHODERHODE ISLANDISLAND WATERSHEDS WATERSHEDS MAP MAP 3 RHODE ISLAND RIVERS COUNCIL ABOUT US The Rhode Island Rivers Council (RIRC) is charged with coordinating state policies to protect rivers and watersheds. Our unique contribution is to strengthen local watershed councils as partners in rivers and watershed protection. Created by statute (RIGL 46-28) in 1991 as an associated function of the Rhode Island Water Resources Board, the RIRC mission is to preserve and improve the quality of Rhode Island's rivers and their watersheds and to work with public entities to develop plans to safely increase river use. Under the Rhode Island Rivers Council statute, rivers are defined as "a flowing body of water or estuary, including streams, creeks, brooks, ponds, coastal ponds, small lakes, and reservoirs." WHAT WE DO The RIRC plays a key role in the state's comprehensive environmental efforts. -

Did You Fall in Love with Blackstone Heritage

Blackstone Heritage Corridor 2018 for a walk, a tour, a GO! bike ride, a paddle, a boat ride, a special event or harvest experience – all in the month of September Proudly in the wonderful Blackstone sponsored by River Valley National Heritage Corridor. GO! Table of Contents Welcome ........................ 2-3 Map ............................... 4 Listing of Experiences & Events ...................... 8-36 Trash Responsibly ........... 15 Be a GearHead! ................ 19 Page 19 Our Newest National Park ..37 Bikeway Maps ............ 38-40 VIP Program .................... 42 Photo Contest ................. 42 Support the Blackstone Heritage Corridor ............ 45 Online Shop .................... 45 Page 37 SEPTEMBER 2018 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Visit us at Page 38-40 BlackstoneHeritageCorridor.org for more free, guided experiences and special events (some may charge fees)! Updated daily. Page 42 670 Linwood Avenue Whitinsville, MA 01588 508-234-4242 BlackstoneHeritageCorridor.org Cover photo by Angie Stormont Page 42 ©2018 Blackstone Heritage Corridor, Inc. Table of Contents 1 The Blackstone River Valley National Heritage We welcome you Corridor is most notably known as the Birthplace to September in the of the American Industrial Revolution and the first place of tolerance and diversity in the Blackstone country. In the fall, its many other attributes come vividly into focus as the crispness of Heritage Corridor! autumn grows from the last warmth of summer. Explore our exceptional National Heritage Corridor during a season of anticipation. Every living thing is in preparation mode. Squirrels and chipmunks are gathering food for the winter. -

Simulated and Observed 2010 Flood-Water Elevations in Selected River Reaches in the Moshassuck and Woonasquatucket River Basins, Rhode Island

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security-Federal Emergency Management Agency Simulated and Observed 2010 Flood-Water Elevations in Selected River Reaches in the Moshassuck and Woonasquatucket River Basins, Rhode Island Scientific Investigations Report 2013–5191 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Front cover. Photograph of Woonasquatucket River flooding on Valley Street looking toward Atwells Avenue, Providence, Rhode Island. Simulated and Observed 2010 Flood-Water Elevations in Selected River Reaches in the Moshassuck and Woonasquatucket River Basins, Rhode Island By Phillip J. Zarriello, David E. Straub, and Stephen M. Westenbroek Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security-Federal Emergency Management Agency Scientific Investigations Report 2013–5191 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2014 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

60 Dams Removed to Restore Rivers in 2010

60 dams removed to restore rivers in 2010 American Rivers releases annual list including dams in California, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, North Carolina, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, Virginia and Vermont. Nationwide, 888 dams have been removed to date. 450 dams have been removed since 1999. Dam removal brings a variety of benefits to local communities, including restoring river health and clean water, revitalizing fish and wildlife, improving public safety and recreation, and enhancing local economies. Working in a variety of functions with partner organizations throughout the country, American Rivers contributed financial and technical support in many of the removals and was solely responsible for the removal of a number of others. Contact information is provided for each dam removal. For further information about the list, please contact Serena McClain, American Rivers’ Director of River Restoration Program at 202.243.7044 or [email protected]. This list includes all known dam removals that occurred in 2010, regardless of the level of American Rivers’ involvement. Dams are categorized by alphabetically by state. Glenbrook Gulch Dam, Glenbrook Gulch (Albion River), California: The 10-foot high Glenbrook Gulch Dam removal restored 0.66 miles of the Albion River for coho and steelhead. The project will also restore instream habitat with the placement of large woody debris, re-establish hydrologic connectivity, and prevent collapse of this earthen structure. Contact: Joe Pecharich (NOAA), (707) 575-6095, [email protected]. Lower Montsweag Dam, Montsweag Brook, Maine: Lower Montsweag Brook Dam acted as a complete barrier to fish passage. The goal of the project was to restore native and diadromous fisheries resources in the lower watershed though removal of the dam, which was completed in early November 2010. -

4 AXLE SINGLE UNIT TRUCKS the Following Restrictions Apply to the Single Unit Vehicles Described in RI General Law (RIGL) 31-25-21

Rhode Island Department of Transportation ANNUAL DIVISIBLE LOAD PERMIT RESTRICTION LIST 4 AXLE SINGLE UNIT TRUCKS The following restrictions apply to the single unit vehicles described in RI General Law (RIGL) 31-25-21. For any single unit vehicle with the number of axles listed here, the following bridges are restricted from crossing due to vehicle weight. The bridge tonnage values below are the maximum tonnage permitted. These restrictions are continuously updated and must be printed and kept in the vehicle associated with the permit as part of the annual permit issued by RIDOT. In case of conflict, posted weight limits at a bridge shall govern over these restrictions.. Carries Crosses City/Town Bridge # Max. Tonnage RI 102 BRONCO HWY BRANCH RIVER Burrillville 067301 24 RI 7 Douglas Pike Branch River Burrillville 010601 36 VICTORY HWY BRANCH RIVER Burrillville 011201 35 RI 114 BROAD ST BLACKSTONE RIVER Central Falls 030501 38 CAHOONE RD BUCKS HORN BROOK Coventry 084501 26 LINCOLN AV PAWTUXET RIVER N BRANCH Coventry 083601 30 NICHOLAS RD ROARING BROOK Coventry 084601 17 Old Flat River Rd Flat River Reservoir Coventry 007201 38 DEAN PKWY WASH SEC BIKE PATH Cranston 034701 29 RI 12 Park Av Elm Lake Brook Cranston 106101 21 RI 37 EB PAWTUXET RIVER Cranston 062801 34 RI 5 OAKLAWN AV WASH SEC BIKE PATH Cranston 028601 38 CHURCH ST P&W RR Cumberland 094301 18 HOWARD RD ABBOTT RUN Cumberland 045951 35 RI 114 Silva Brook Cumberland 020501 34 RI 114 DMND HLL RD I-295 NB & SB Cumberland 075401 17 Tillinghast Rd Frenchtown Brook East Greenwich 119801 27 LYON AV I-195 EB & WB East Providence 046901 32 POTTER ST I-195 EB & WB East Providence 046701 34 PURCHASE ST I-195 EB & WB East Providence 046801 32 RI 114A Mink St Runnins River East Providence 020901 18 River Road Runnins River East Providence 021401 29 SEEKONK RIVER CROS SEEKONK RIVER & CITY STS East Providence 060001 25 WATERMAN AV P&W RR R.O.W. -

WOONASQUATUCKET RIVER CENTREDALE MANOR SITE, NORTH PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND by Peter E

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR PREPARED IN COOPERATION WITH THE OPEN–FILE REPORT 00-276 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY Church, P.E., Lyford, F.P., and Clifford, Scott, 2000, Map showing distribution of organic compounds at ground water-surface water interface, North Providence Rhode Island CENTREDALE MANOR SITE LOCATION VOLATILE ORGANIC COMPOUNDS IN VAPOR DIFFUSION SAMPLES 71˚45' MASSACHUSETTS Waterman Ave IN THE RIVER, CENTREDALE MANOR SITE, 42˚00' 44 NORTH PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND NORTH PROVIDENCE EXPLANATION RHODE Mineral Spring Ave VS-009VS-009 VAPOR DIFFUSION SAMPLER AND 71˚15' W O North ISLAND (40) O (40) IDENTIFIER—Total vapor concentration detected in N A CENTERDALE MANOR S SITE LOCATION target compounds, in parts per billion by volume (in Q U CONNECTICUT A parentheses) T U C K 44 ET VS-020-D VS-020-D VAPOR DIFFUSION SAMPLER WITH DUPLICATE R IV (116) E (116) SAMPLER AND IDENTIFIER— Total vapor JOHNSTON R concentration detected in target compounds in primary 41˚30' 963,500 sampler, in parts per billion by volume (in parentheses) 963,000 Waterman Rd VS-001VS-001 VAPOR DIFFUSION SAMPLER AND IDENTIFIER— (Trace) (Trace) All vapor concentrations detected in target compounds 0 10 MILES VVS-001S-001 VS-001 0 0 FEET below minimum reporting limits, in parts per billion by Long Island Sound 0 900 FEET [ ((TTrrace)ace) volume (in parentheses) 0 10 KILOMETERS BLOCK 0 150 METERS ISLAND VS-002VS-002 VS-109VS-109 VAPOR DIFFUSION SAMPLER AND IDENTIFIER— (ND)(ND) (ND)(ND) Vapor concentrations not detected above minimum reporting limits in target compounds VS-003VS-003 VS-062 (T(Trace)race) VS-062 VAPOR DIFFUSION SAMPLER AND 15,213,500 (NS)(NS) IDENTIFIER—Sampler not retrieved U.S VOLATILE ORGANIC COMPOUNDS IN VAPOR-DIFFUSION SAMPLES . -

Estimated Water Use and Availability in the Lower Blackstone River Basin, Northern Rhode Island and South-Central Massachusetts, 1995–99

Cover photo: The Abbott Run Reservoir, photo taken November 25, 2003. U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Estimated Water Use and Availability in the Lower Blackstone River Basin, Northern Rhode Island and South-Central Massachusetts, 1995–99 By LORA K. BARLOW Water-Resources Investigations Report 03-4190 In cooperation with the RHODE ISLAND WATER RESOURCES BOARD Providence, Rhode Island 2003 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GALE A. NORTON, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: Subdistrict Chief U.S. Geological Survey Massachusetts–Rhode Island District Branch of Information Services U.S. Geological Survey Box 25286 275 Promenade, Suite 150 Denver, CO 80225-0286 Providence, RI 02908 or visit our Web site at http://ri.water.usgs.gov CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction......................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Purpose and Scope.................................................................................................................................................... 2