Blackstone River Watershed Needs Assessment Project Report—July 23, 2021 Draft, Page I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RHODE ISLAND RIVERS COUNCIL HISTORICAL OUTLINE 1989-1990: Lieutenant Governor's Task Force on Rivers, Final Report & Recommendations, 58 Pages, February, 1990

RHODE ISLAND RIVERS COUNCIL HISTORICAL OUTLINE 1989-1990: Lieutenant Governor's Task Force on Rivers, Final Report & Recommendations, 58 pages, February, 1990. 1991-2000: Governor Bruce Sundlun inaugurated January 1, 1991. General Assembly created RI Rivers Council (RC) – RI General Law 46-28. Kenneth Payne became RC chair. Statewide Planning Program provides staff support to RC. RC concluded in 1992 that "more effective integration of existing programs and authority for rivers is needed." RC formulated draft classifications for rivers in 1993. RC held four workshops in northern, central, southern and eastern RI in 1994 to refine draft river classifications. Governor Lincoln Almond inaugurated January 1, 1995. Michael Cassidy, Planner for the City of Pawtucket, became RC chair. RC, working with the Divison of Planning, created digital maps of the state's watersheds. The State Planning Council adopted the RI Rivers Policy and Classification Plan, in January 1998, as State Guide Plan Element 162. RC established policies for recognizing local watershed councils in 1998. The Blackstone, Saugatucket and Wood-Pawcatuck were first river systems to have watershed councils designated by RC. Note: Designated watershed councils have certain legal authority and standing to represent their water bodies in state and local jurisdictions as well as be eligible for state grants via RC. 2001-2007: Meg Kerr became RC chair. General Assembly commences in 2001 providing annual legislative grants to RC from $22,000 to $52,000 range. Annual grant rounds commence from RC to designated local watershed councils generally in $2,500 to $7,500 range from Fiscal Year 2002 to the present. -

In the Woonasquatucket River Watershed

Public Outreach & Education A Model Based on Rhode Island’s Woonasquatucket River “Do’s & Don’ts” Education Program Strategies and Programs Developed, Implemented and Compiled by Northern Rhode Island Conservation District, RI Urban Rivers Team—Health & Education Subcommittee, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Table of Contents Section Title Page Why Use this project as a Model? / ii-iii Timeframe of Events for the Woonasquatucket River “Do’s & Don’ts” Background / iv-v Using this Tool Kit Step 1 Understand the Target Watershed 2-3 Step 2 Identify the Administrative Agency 4-5 Step 3 Develop a Steering Committee 6-7 Step 4 Identify Key Messages 8-9 Step 5 Identify Target Audiences 10-11 Steps Program Ideas for Various Audiences (12-15) 5A Step 5A: Signage & Brochures 12 5B Step 5B: Adult Audiences 13 5C Step 5C: Child Audiences 14 5D Step 5D: Facilitating Community Involvement 15 Step 6 Develop a Program for Implementation 16-17 Step 7 Finding Sustainable Funding Sources 18-19 Step 8 Program Evaluation 20-21 Appendices & Template Location 22-23 Evaluation of the Tool Kit Post- Appendices Acknowledgments: This publication was made possible by the efforts of dedicated individuals. We would like to thank them for all of their input, time, and expertise. ¨ US EPA—Urban Environmental Program ¨ Socio-Economic Development Center for ¨ Northern RI Conservation District Southeast Asians ¨ Audubon Society of RI ¨ Olneyville Housing Corporation ¨ RI Department of Health (HEALTH) ¨ The City of Providence ¨ RI Department of Environmental ¨ Narragansett Bay Commission Management (RIDEM) ¨ Save the Bay ¨ Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council ¨ Environmental Diversity Education Forum and the Greenway Project ¨ Urban League of RI ¨ Club Neopolsi Creations ¨ International Language Bank This publication was designed and compiled by Kate J. -

Views of the Blackstone River and the Mumford River

THE SHlNER~ AND ITS USE AS A SOURCE OF INCOME IN WORCESTER, AND SOUTHEASTERN WORCESTER COUNTY, MASSACHUSETTS By Robert William Spayne S.B., State Teachers College at Worcester, Massachusetts 19,3 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Oberlin College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Geography CONTENTS Ie INTRODUCTION Location of Thesis Area 1 Purpose of Study 1 Methods of Study 1 Acknowledgments 2 II. GEOGRAPHY OF SOUTHERN WORCESTER COUNTY 4 PIiYSICAL GEOGRAPHY 4 Topography 4 stream Systems 8 Ponds 11 Artificial 11 Glacial 12 Ponds for Bait Fishing 14 .1 oJ Game Fishing Ponds 15 Climatic Characteristics 16 Weather 18 POPULATION 20 Size of Population 20 Distribution of Population 21 Industrialization 22 III. GEOGRAPHICAL BASIS FOR TEE SHINER INDUSTRY 26 Recreational Demands 26 Game Fish Resources 26 l~umber of ;Ponds 28 Number of Fishermerf .. 29 Demand for Bait 30 l IV. GENERAL NATURE OF THE BAIT INDUSTRY 31 ,~ Number of Bait Fishermen 31 .1 Range in Size of Operations 32 Nature of Typical Operations 34 Personality of the Bait Fishermen 34 V. THE SHINER - ITS DESCRIPTION, HABITS AND , CHARACTERISTICS 35 VI. 'STANDARD AND IlIIlPROVISED EQUIPMENT USED IN .~ THE IhllUSTRY 41 Transportation 41 Keeping the Bait Alive 43 Foul Weather Gear 47 Types of Nets 48 SUCCESSFUL METHODS USED IN NETTING BAIT 52 Open Water Fishing 5'2 " Ice Fishing 56 .-:-) VII. ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE OF THE SHINER INDUSTRY ~O VIII. FUTURE OUTLOOK FOR THE SHINER INDUSTRY 62 IX. BIBLIOGRAPHY 69 x. APPENDIX 72 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Following Page . -

Woonasquatucket: American Heritage River

The Woonasquatucket: An American Heritage River Page 1 of 1 Superfund Records Center SITE: C__i__=la ie BREAK: OTHER no _ Donate Now! 4^04-0 3 WOONASQUATUCKET RIVER WATERSHED COUNCIL Home About UsD About the Watershed • Events Projects D Get Involved • Links Things to Buy The Woonasquatucket: An American Heritage More About Us: River • Who We Are & What We Do • In The News 'Tonight, I announce that this year I will designate 10 American Heritage An American Heritage River Rivers, to help communities alongside them revitalize their waterfronts and clean up pollution in the rivers, proving once again that we can grow • Our Staff the economy as we protect the environment." - President Clinton's 1997 • Our Funders State ofthe Union Address • Our Board • Employment Opportunities On July 30,1998 President Clinton designated the Woonasquatucket River as an American Heritage River. The Woonasquatucket is partnered • Way sto Contact Us with the Blackstone River for the purposes of this program. Senator John H. Chafee nominated the Woonasquatucket and Blackstone Rivers for this designation. The proposal received immediate and strong support from Senator Jack Reed, Representative Weygand, Representative Kennedy, and Governor Almond, and residents ofthe 6 communities along the River, including Glocester, North Smithfield, Smithfield, Johnston, North Providence and Providence. The river was chosen in part because ofthe significant role it played in the Industrial Revolution. The Woonasquatucket was one ofthe first rivers to be dammed by mill-owners to insure a steady Undated photograph of Riverside Mills in Providence. supply of water year-round for their mills. In the last thirty years, The building in the foreground still exists. -

ATTENDANCE: A. Members Present

The Rhode Island Rivers Council c/o RI Water Resources Board One Capitol Hill Providence, RI 02908 www.ririvers.org [email protected] Minutes of RIRC Meeting Wednesday, June 12, 2019 Meeting – 4 pm DEM Office of Water Resources – Conference Room 280C 235 Promenade Street, Providence, RI ATTENDANCE: A. Members Present: Veronica Berounsky, Chair Alicia Eichinger, Vice Chair Charles Horbert Walter Galloway Rachel Calabro Ernie Panciera Eugenia Marks B. Guests in Attendance: Elise Torello, Wood-Pawcatuck Watershed Association Michael Zarum, Buckeye Brook Coalition Jennifer Paquet, RI DEM Douglas Stephens, Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council Michael Bradlee, Friends of the Moshassuck Julia Bancroft, Narragansett Bay Estuary Program Susan Kiernan, RI DEM John Zwarg, RI DEM Betsy Dake, RI DEM Arthur Plitt, Blackstone River Watershed Council – Friends of the Moshassuck Margherita Pryor, US EPA Chelsea Glinna, VHB Introductions: All attending board members and guests introduced themselves. Prior to the start of the RIRC Meeting, representatives were available from RI DEM to provide a presentation and give the Watershed Councils an update on things they are working on. Updates were provided on multiple topics as follows: RI Non-Point Source Management Plan: This is overseen by EPA, and is required by Section 319 of the Clean Water Act. The plan is consistent with the State’s “Water Quality 2035” plan Plan elements were described Water quality conditions (descriptive) Management Framework Rules Statewide Priorities Implementation It has a five-year planning horizon focused on RIDEM actions. Priorities include stormwater; OWTS, agriculture, road salt, turf management, pet waste, and “other” sources. Other acknowledged stressors include: wetland alterations; aquatic invasives, stream connectivity, water withdrawals, and climate change. -

Geological Survey

imiF.NT OF Tim BULLETIN UN ITKI) STATKS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 115 A (lECKJKAPHIC DKTIOXARY OF KHODK ISLAM; WASHINGTON GOVKRNMKNT PRINTING OFF1OK 181)4 LIBRARY CATALOGUE SLIPS. i United States. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Department of the interior | | Bulletin | of the | United States | geological survey | no. 115 | [Seal of the department] | Washington | government printing office | 1894 Second title: United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Rhode Island | by | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] | Washington | government printing office 11894 8°. 31 pp. Gannett (Henry). United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Khode Island | hy | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] Washington | government printing office | 1894 8°. 31 pp. [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Bulletin 115]. 8 United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | * A | geographic dictionary | of | Ehode Island | by | Henry -| Gannett | [Vignette] | . g Washington | government printing office | 1894 JS 8°. 31pp. a* [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (Z7. S. geological survey). ~ . Bulletin 115]. ADVERTISEMENT. [Bulletin No. 115.] The publications of the United States Geological Survey are issued in accordance with the statute approved March 3, 1879, which declares that "The publications of the Geological Survey shall consist of the annual report of operations, geological and economic maps illustrating the resources and classification of the lands, and reports upon general and economic geology and paleontology. The annual report of operations of the Geological Survey shall accompany the annual report of the Secretary of the Interior. All special memoirs and reports of said Survey shall be issued in uniform quarto series if deemed necessary by tlie Director, but other wise in ordinary octavos. -

Waterbody Name Lat Long Location Town Stage Ruler Rationale Number # Subwatershed A-01-01-010 BB010 No Beaver Brook Beaver Brook Jewish Comm

Master Site List 2007 Site Rev. Site Watershed CWF Waterbody Name Lat Long Location Town Stage Ruler Rationale Number # Subwatershed A-01-01-010 BB010 No Beaver Brook Beaver Brook Jewish Comm. 42.29549 -71.83817 On footbridge located south of Worcester On footbridge Baseline near beginning Ctr. northerly driveway at 633 of Beaver Brook Salisbury St. at the Jewish Community Center A-01-01-030 BB030 No Beaver Brook Beaver Brook Park Ave. 42.25028 -71.83142 Upstream of confluence of Worcester On abutment on To compare with Carwash Beaver Brook and Tatnuck south side of street Tatnuck Brook just Brook at Clark Fields carwash on above confluence Park Ave. A-02-01-010 BMB010 No Broad Meadow Broad Meadow Dunkirk 42.24258 -71.77599 At end of Dunkirk Ave, slightly Worcester Baseline where brook Brook Brook downstram of culvert. outfalls from culvert A-02-01-020 BMB020 No Broad Meadow Broad Meadow Dupuis Ave. 42.23554 -71.77297 Walk around lawn. Just before Worcester To monitor impacts of Brook Brook Beaver Brook enters pipe 50' Beaver Dam - see how upstream of pipe. quality improves after going through natural area A-02-01-040 BMB040 No Broad Meadow Broad Meadow Holdridge 42.23092 -71.76782 Downstream of stone bridge on Worcester 15 feet below Midway on course Brook Brook Holdridge Trail - on the west stone bridge on through wildlife sanctuary bank tree A-02-01-050 BMB050 No Broad Meadow Broad Meadow Dosco 42.19267 -71.75017 Beside Dosco Sheet Metal Millbury Attached to Dorothy Brook as it flows Brook Brook Company; 30 yards downstream concrete wall into the Blackstone River from Grafton St. -

West River Stream Team Shoreline Survey Report & Action Plan

%ODFNVWRQH5LYHU:DWHUVKHG$VVRFLDWLRQ :HVW5LYHU6WUHDP7HDP 6KRUHOLQH6XUYH\5HSRUW $FWLRQ3ODQ June 30, 2007 Thanks to: Commonwealth of Massachusetts Riverways Adopt-A-Stream Program and UNIBANK for their assistance in funding this project. Special thanks go out to our valued Stream Team members without whom this project would not be possible; West River area residents, businesses, and landowners for their cooperation; the Blackstone River and Canal Heritage State Park at River Bend Farm; and the Town of Uxbridge, especially the Uxbridge Conservation Commission. Preface The West River Stream Team members Erin, Steve, Jeremy, and Jack Bennett John and Elaine Czebotar William Dausey Barbara Johnson Mike, Tom, and Phil McMullin Gwyn Mills Joel Morgenstern Joan Newton Scot, Marie, and Andrea Pendleton Katherine Smith Charley Sweet James Plasse Michael Pouliot Michelle Walsh Commonwealth of Massachusetts Riverways Adopt-a-Stream Advisor Gabrielle Stebbins, Adopt-A-Stream Program Coordinator Blackstone River Watershed Association Project Coordinator Michelle Walsh, Environmental Outreach Coordinator Project Coordination Michelle Walsh, Environmental Outreach Coordinator for the Blackstone River Watershed Association (BRWA) advertised for volunteers in various media throughout the Blackstone Valley area including but not limited to press releases in local newspapers, announcements on local cable channels, letters to environmental organizations, high schools, Boy Scout troops and town officials, flyers and e-mails to various environmental organizations. A shoreline survey training session was scheduled at River Bend Farm in Uxbridge, MA on May 14, 2007. Approximately forty volunteers attended the meeting. At this meeting, volunteers were instructed on how to conduct a shoreline survey and were given survey sheets. After the meeting, the West River was sectioned into 9 reaches; volunteers were organized in teams and selected a section of the River to survey. -

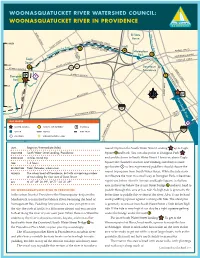

Woonasquatucket River in Providence95

WOONASQUATUCKET RIVER WATERSHED COUNCIL: Miles 1 SMITH STREET ORMS STREET WOONASQUATUCKET RIVER IN PROVIDENCE95 RIVER AVENUE RI State M o s House h PROMENADE STREET a s s 0 MILES u c k Mall KINSLEY AVENUE R VALLEY STREET River ket i uc 5 v at e ANGELL STREET ACORN 4 u r 1 sq STREET Waterplace na oo Park 3 W WATERMAN AVENUE Eagle ORIAL B .5 M O COLLEGE STREET ME U LE Square V A 0.25 R HARRIS AVENUE 6 Downtown D ATWELLS AVENUE 6 10 Providence BENEFIT STREET SOUTHMAIN WATER STREET ST ATWELLS AVENUE Donigian 7 2 Park 8 1A 25 DYER STREET 0. DEAN STREET 0.5 1 1 BROADWAY Providence River BIKE PATH 00 0.75 95 POST ROAD POINT WESTMINSTER STREET STREET Ninigret mAP LEGEND 9 Park 6 WATER ACCESS l POINTS OF INTEREST n P PARKING 195 n WATER ROADS BIKE PATH CAUTION CONSERVATION LAND u 10 n ELMWOOD AVE LEVEL Beginner/Intermediate (tides) round trip from the South Water Street Landing 1 up to Eagle START/END South Water Street Landing, Providence Square l6 and back. You can also put in at Donigian Park 8 RIVER MILES 4 miles round trip and paddle down to South Water Street. However, above Eagle TIME 1-2 hours Square the channel is narrow and winding and there is some 7 DESCRIPTION Tidal, flatwater, urban river quickwater u so less experienced paddlers should choose the round-trip option from South Water Street. While the tide starts SCENERY The urban heart of Providence, but with a surprising number of trees along the river west of Dean Street to influence the river in a small way at Donigian Park, it becomes 295 GPS N 41º 49’ 20.39”, W 71º 24’ 21.49” significant below Atwells Avenue and Eagle Square. -

Bristol County, Massachusetts (All Jurisdictions)

VOLUME 2 OF 4 BRISTOL COUNTY, MASSACHUSETTS (ALL JURISDICTIONS) Bristol County COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NUMBER ACUSHNET, TOWN OF 250048 ATTLEBORO, CITY OF 250049 BERKLEY, TOWN OF 250050 DARTMOUTH, TOWN OF 250051 DIGHTON, TOWN OF 250052 EASTON, TOWN OF 250053 FAIRHAVEN, TOWN OF 250054 FALL RIVER, CITY OF 250055 FREETOWN, TOWN OF 250056 MANSFIELD, TOWN OF 250057 NEW BEDFORD, CITY OF 255216 NORTH ATTLEBOROUGH, TOWN OF 250059 NORTON, TOWN OF 250060 RAYNHAM, TOWN OF 250061 REHOBOTH, TOWN OF 250062 SEEKONK, TOWN OF 250063 SOMERSET, TOWN OF 255220 SWANSEA, TOWN OF 255221 TAUTON, CITY OF 250066 WESTPORT, TOWN OF 255224 REVISED JULY 16, 2014 FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 25005CV002B NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study (FIS) may not contain all data available within the repository. It is advisable to contact the community repository for any additional data. Selected Flood Insurance Rate Map panels for the community contain information that was previously shown separately on the corresponding Flood Boundary and Floodway Map panels (e.g., floodways, cross sections). In addition, former flood hazard zone designations have been changed as follows: Old Zone New Zone A1 through A30 AE V1 through V30 VE (shaded) B X C X Part or all of this Flood Insurance Study may be revised and republished at any time. In addition, part of this Flood Insurance Study may be revised by the Letter of Map Revision process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the Flood Insurance Study. -

Town of Upton Open Space and Recreation Plan

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ MAY 2011 TOWN OF UPTON D OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN a f North t Prepared by: Upton Open Space Committee (A Subcommittee of the Upton Conservation Commission) ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Town of Upton D OPEN SPACE rAND RECREATION PLAN a f t May 2011 Prepared by: The Upton Open Space Committee (A Subcommittee of the Upton Conservation Commission) Town of Upton Draft Open Space and Recreation Plan – May 2011 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________ DEDICATION The members of the Open Space Committee wish to dedicate this Plan to the memory of our late fellow member, Francis Walleston who graciously served on the Milford and Upton Conservation Commissions for many years. __________________________________________________________________ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Upton Open Space Committee Members Tom Dodd Scott Heim Rick Holmes Mike Penko Marcella Stasa Bill Taylor Assistance was provided by: Stephen Wallace (Central Massachusetts Regional Planning Commission) Peter Flinker and Hillary King (Dodson Associates) Dave Adams (Chair, Upton Recreation Commission) Chris Scott (Chair, Upton Conservation Commission) Ken Picard (as a Member of the Upton Planning Board) Upton Board of Selectmen. Trish Settles (Central Massachusetts Regional Planning Commission) __________________________________________________________________ -

2018 Annual Report

THE POWER OF OUR NETWORK ANNUAL 2018 REPORT 2018 BY THE NUMBERS CELEBRATING 30 YEARS AND THE VIBRANT FUTURE OF OUR NETWORK 4,146 500 River Network was founded thirty years ago to strengthen local efforts to protect rivers. Over three INDIVIDUALS HOURS OF SUPPORT educated through decades our focus has remained remarkably consistent: We connect people to save rivers. That provided in simple tagline belies a tremendous amount of action to protect and restore waters across the country, particularly at the local level. Today this network is over 6,000 strong. 88 38 As backbone to this network, we educate and empower champions to effectively engage their EVENTS (River Rally, communities, influence decision makers, assert their opinion on policy change, and translate DIRECT strategies from our national network into local solutions for healthy rivers and clean water. Every webinars, and workshops) CONSULTATIONS day, thousands of these local champions are working across the U.S. Take a moment to meet our network and learn their stories. River Network began by helping river and watershed organizations expand protections for $80,000 13,385 pristine rivers. Since then our ambitions, leadership, and programs have evolved to align with our SCHOLARSHIPS granted to understanding of what rivers need to remain healthy, the challenges of a changing climate, and VOLUNTEERS attended significant shifts in the social, political, and economic context of water. While remaining committed to bolstering local groups and grassroots efforts, we now build Nicole Silk 141 24 coalitions across sectors—uniting NGOs, tribal nations, government agencies, and businesses RIVER RALLY PARTICIPANTS RIVER NETWORK to achieve bigger impacts.