The Construction of Emptiness and the Re- Colonisation of Detroit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English, French, and Spanish Colonies: a Comparison

COLONIZATION AND SETTLEMENT (1585–1763) English, French, and Spanish Colonies: A Comparison THE HISTORY OF COLONIAL NORTH AMERICA centers other hand, enjoyed far more freedom and were able primarily around the struggle of England, France, and to govern themselves as long as they followed English Spain to gain control of the continent. Settlers law and were loyal to the king. In addition, unlike crossed the Atlantic for different reasons, and their France and Spain, England encouraged immigration governments took different approaches to their colo- from other nations, thus boosting its colonial popula- nizing efforts. These differences created both advan- tion. By 1763 the English had established dominance tages and disadvantages that profoundly affected the in North America, having defeated France and Spain New World’s fate. France and Spain, for instance, in the French and Indian War. However, those were governed by autocratic sovereigns whose rule regions that had been colonized by the French or was absolute; their colonists went to America as ser- Spanish would retain national characteristics that vants of the Crown. The English colonists, on the linger to this day. English Colonies French Colonies Spanish Colonies Settlements/Geography Most colonies established by royal char- First colonies were trading posts in Crown-sponsored conquests gained rich- ter. Earliest settlements were in Virginia Newfoundland; others followed in wake es for Spain and expanded its empire. and Massachusetts but soon spread all of exploration of the St. Lawrence valley, Most of the southern and southwestern along the Atlantic coast, from Maine to parts of Canada, and the Mississippi regions claimed, as well as sections of Georgia, and into the continent’s interior River. -

The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU 17th Annual Africana Studies Student Research Africana Studies Student Research Conference Conference and Luncheon Feb 13th, 1:30 PM - 3:00 PM The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa Erin Myrice Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons Myrice, Erin, "The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa" (2015). Africana Studies Student Research Conference. 2. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf/2015/004/2 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Events at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies Student Research Conference by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa Erin Myrice 2 “An African poet, Taban Lo Liyong, once said that Africans have three white men to thank for their political freedom and independence: Nietzsche, Hitler, and Marx.” 1 Marx raised awareness of oppressed peoples around the world, while also creating the idea of economic exploitation of living human beings. Nietzsche created the idea of a superman and a master race. Hitler attempted to implement Nietzsche’s ideas into Germany with an ultimate goal of reaching the whole world. Hitler’s attempted implementation of his version of a ‘master race’ led to one of the most bloody, horrific, and destructive wars the world has ever encountered. While this statement by Liyong was bold, it held truth. The Second World War was a catalyst for African political freedom and independence. -

World Geography: Unit 6

World Geography: Unit 6 How did the colonization of Africa shape its political and cultural geography? This instructional task engages students in content related to the following grade-level expectations: • WG.1.4 Use geographic representations to locate the world’s continents, major landforms, major bodies of water and major countries and to solve geographic problems • WG.3.1 Analyze how cooperation, conflict, and self-interest impact the cultural, political, and economic regions of the world and relations between nations Content • WG.4.3 Identify and analyze distinguishing human characteristics of a given place to determine their influence on historical events • WG.4.4 Evaluate the impact of historical events on culture and relationships among groups • WG.6.3 Analyze the distribution of resources and describe their impact on human systems (past, present, and future) In this instructional task, students develop and express claims through discussions and writing which Claims examine the effect of colonization on African development. This instructional task helps students explore and develop claims around the content from unit 6: Unit Connection • How does the history of colonization continue to affect the economic and social aspects of African countries today? (WG.1.4, WG.3.1, WG.4.3, WG.4.4, WG.6.3) Formative Formative Formative Formative Performance Task 1 Performance Task 2 Performance Task 3 Performance Task 4 How and why did the How did European What perspectives exist How did colonization Supporting Questions colonization of Africa countries politically on the colonization of impact Africa? begin? divide Africa? Africa? Students will analyze Students will explore Students will analyze Students will examine the origins of the European countries political cartoons on the lingering effects of Tasks colonization in Africa. -

Prohibition's Proving Ground: Automobile Culture and Dry

PROHIBITION’S PROVING GROUND: AUTOMOBILE CULTURE AND DRY ENFORCEMENT ON THE TOLEDO-DETROIT-WINDSOR CORRIDOR, 1913-1933 Joseph Boggs A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2019 Committee: Michael Brooks, Advisor Rebecca Mancuso © 2019 Joseph Boggs All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Michael Brooks, Advisor The rapid rise of an automobile culture in the 1910s and 20s provided ordinary North Americans greater mobility, freedom, privacy, and economic opportunity. Simultaneously, the United States and Canada witnessed a surge in “dry” sentiments and laws, culminating in the passage of the 18th Amendment and various provincial acts that precluded the outright sale of alcohol to the public. In turn, enforcement of prohibition legislation became more problematic due to society’s quick embracing of the automobile and bootleggers’ willingness to utilize cars for their illegal endeavors. By closely examining the Toledo-Detroit-Windsor corridor—a region known both for its motorcar culture and rum-running reputation—during the time period of 1913-1933, it is evident why prohibition failed in this area. Dry enforcers and government officials, frequently engaging in controversial policing tactics when confronting suspected motorists, could not overcome the distinct advantages that automobiles afforded to entrepreneurial bootleggers and the organized networks of criminals who exploited the transnational nature of the region. vi TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER I. AUTOMOBILITY ON THE TDW CORRIDOR ............................................... 8 CHAPTER II. MOTORING TOWARDS PROHIBITION ......................................................... 29 CHAPTER III. TEST DRIVE: DRY ENFORCEMENT IN THE EARLY YEARS .................. 48 The Beginnings of Prohibition in Windsor, 1916-1919 ............................................... -

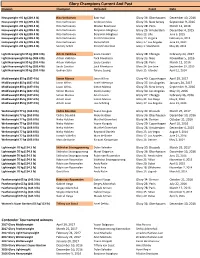

Glory Champions Current and Past Division Champion Defeated Event Date

Glory Champions Current And Past Division Champion Defeated Event Date Heavyweight +95 kg (209.4 lb) Rico Verhoeven Badr Hari Glory 36: Oberhausen December 10, 2016 Heavyweight +95 kg (209.4 lb) Rico Verhoeven Anderson Silva Glory 33: New Jersey September 9, 2016 Heavyweight +95 kg (209.4 lb) Rico Verhoeven Mladen Brestovac Glory 28: Paris March 12, 2016 Heavyweight +95 kg (209.4 lb) Rico Verhoeven Benjamin Adegbuyi Glory 26: Amsterdam December 4, 2015 Heavyweight +95 kg (209.4 lb) Rico Verhoeven Benjamin Adegbuyi Glory 22: Lille June 5, 2015 Heavyweight +95 kg (209.4 lb) Rico Verhoeven Errol Zimmerman Glory 19: Virginia February 6, 2015 Heavyweight +95 kg (209.4 lb) Rico Verhoeven Daniel Ghiță Glory 17: Los Angeles June 21, 2014 Heavyweight +95 kg (209.4 lb) Semmy Schilt Errol Zimmerman Glory 1: Stockholm May 26, 2012 Light Heavyweight 95 kg (209.4 lb) Artem Vakhitov Saulo Cavalari Glory 38: Chicago February 24, 2017 Light Heavyweight 95 kg (209.4 lb) Artem Vakhitov Zack Mwekassa Glory 35: Nice November 5, 2016 Light Heavyweight 95 kg (209.4 lb) Artem Vakhitov Saulo Cavalari Glory 28: Paris March 12, 2016 Light Heavyweight 95 kg (209.4 lb) Saulo Cavalari Zack Mwekassa Glory 24: San Jose September 19, 2015 Light Heavyweight 95 kg (209.4 lb) Gökhan Saki Tyrone Spong Glory 15: Istanbul April 12, 2014 Middleweight 85 kg (187.4 lb) Simon Marcus Jason Wilnis Glory 40: Copenhagen April 29, 2017 Middleweight 85 kg (187.4 lb) Jason Wilnis Israel Adesanya Glory 37: Los Angeles January 20, 2017 Middleweight 85 kg (187.4 lb) Jason Wilnis Simon Marcus -

The Anti-Gang Initiative in Detroit: an Aggressive Enforcement Approach to Gangs Timothy S

Roger Williams University DOCS@RWU School of Justice Studies Faculty Papers School of Justice Studies 1-1-2002 The Anti-Gang Initiative in Detroit: An Aggressive Enforcement Approach to Gangs Timothy S. Bynum Michigan State University Sean P. Varano Roger Williams University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.rwu.edu/sjs_fp Part of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Bynum, T.S., and Varano, S.P. 2002. “The Anti-Gang Initiative in Detroit: An Aggressive Enforcement Approach to Gangs.” In Gangs, Youth Violence and Community Policing, edited by S.H. Decker. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Justice Studies at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Justice Studies Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHAPTER 9 THE ANTI-GANG INITIATIVE IN DETROIT 215 9 CRIME PATTERNS Detroit's crime trends show a mixed pattern. While the levels of some major crimes have attenuated in the past several years, the decline has not been as dramatic in other crime categories. Although the frequency and rate of violent crimes such as murder and robbery have decreased during recent years, there were troubling increases in aggravated assaults and burglary between 1995 and The Anti-Gang lriitiative 1998. Table 9.1 details changes in Detroit's crime between 1995 and 1999.2 Data in Detroit reflect both the total number of reported crimes in each crime category, and crime rates per 100,000. -

Colonialism and Economic Development in Africa

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES COLONIALISM AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN AFRICA Leander Heldring James A. Robinson Working Paper 18566 http://www.nber.org/papers/w18566 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 November 2012 We are grateful to Jan Vansina for his suggestions and advice. We have also benefitted greatly from many discussions with Daron Acemoglu, Robert Bates, Philip Osafo-Kwaako, Jon Weigel and Neil Parsons on the topic of this research. Finally, we thank Johannes Fedderke, Ewout Frankema and Pim de Zwart for generously providing us with their data. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2012 by Leander Heldring and James A. Robinson. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Colonialism and Economic Development in Africa Leander Heldring and James A. Robinson NBER Working Paper No. 18566 November 2012 JEL No. N37,N47,O55 ABSTRACT In this paper we evaluate the impact of colonialism on development in Sub-Saharan Africa. In the world context, colonialism had very heterogeneous effects, operating through many mechanisms, sometimes encouraging development sometimes retarding it. In the African case, however, this heterogeneity is muted, making an assessment of the average effect more interesting. -

The Detroit Food System Report 2009-2010

Wayne State University Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Research Urban Studies and Planning Publications 5-5-2011 The etrD oit Food System Report 2009-2010 Kameshwari Pothukuchi Wayne State University, [email protected] Recommended Citation Pothukuchi, K. (2011). The Detroit Food System Report, 2009-10. Detroit: Detroit Food Policy Council. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/urbstud_frp/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Urban Studies and Planning at DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Research Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. TheDetroit Food System Report 2009-2010 Prepared by Kami Pothukuchi, Ph.D., Wayne State University For the Detroit Food Policy Council May 15, 2011 The Detroit Food Policy Council Membership, April 2011 Members Sector Represented Members Sector Represented Malik Yakini, Chair K-12 Schools Lisa Nuszkowski Mayoral Appointee Nsoroma Institute City of Detroit Kami Pothukuchi, Vice Chair Colleges and Universities Sharon Quincy Dept. of Health & Wellness Wayne State University, SEED Wayne City of Detroit Promotion Appointee Ashley Atkinson, Secretary Sustainable Agriculture Department of Health and Wellness Promotion The Greening of Detroit Olga Stella Urban Planning Charles Walker, Treasurer Retail Food Stores Detroit Economic Growth Corporation Marilyn Nefer Ra Barber At Large Kathryn Underwood City Council Appointee Detroit Black Community Food Security Network Detroit -

Illicit Economies in the Detroit- Windsor Borderland, 1945-1960

Ambassadors of Pleasure: Illicit Economies in the Detroit- Windsor Borderland, 1945-1960 by Holly Marie Karibo A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy History Department University of Toronto © Copyright by Holly Karibo (2012) Ambassadors of Pleasure: Illicit Economies in the Detroit-Windsor Borderland, 1945-1960 Holly Karibo Doctor of Philosophy History Department University of Toronto 2012 Abstract “Ambassadors of Pleasure” examines the social and cultural history of ‘sin’ in the Detroit-Windsor border region during the post-World War II period. It employs the interrelated frameworks of “borderlands” and “vice” in order to identify the complex ways in which illicit economies shaped—and were shaped by—these border cities. It argues that illicit economies served multiple purposes for members of local borderlands communities. For many downtown residents, vice industries provided important forms of leisure, labor, and diversion in cities undergoing rapid changes. Deeply rooted in local working-class communities, prostitution and heroin economies became intimately intertwined in the daily lives of many local residents who relied on them for both entertainment and income. For others, though, anti-vice activities offered a concrete way to engage in what they perceived as community betterment. Fighting the immoral influences of prostitution and drug use was one way some residents, particularly those of the middle class, worked to improve their local communities in seemingly tangible ways. These II struggles for control over vice economies highlight the ways in which shifting meanings of race, class, and gender, growing divisions between urban centers and suburban regions, and debates over the meaning of citizenship evolved in the urban borderland. -

Crime and Poverty in Detroit: a Cross-Referential Critical Analysis of Ideographs and Framing

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 4-11-2014 Crime And Poverty In Detroit: A Cross-Referential Critical Analysis Of Ideographs And Framing Jacob Jerome Nickell Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Nickell, Jacob Jerome, "Crime And Poverty In Detroit: A Cross-Referential Critical Analysis Of Ideographs And Framing" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 167. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/167 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CRIME AND POVERTY IN DETROIT: A CROSS-REFERENTIAL CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF IDEOGRAPHS AND FRAMING Jacob J. Nickell 135 Pages May 2014 This thesis examines how the relationship between crime and poverty is rhetorically constructed within the news media. To this end, I investigate the content of twelve news articles, published online, that offered coverage of crime in the city of Detroit, Michigan. I employ three methods in my criticism of these texts: ideographic analysis, critical framing analysis, and an approach that considers ideographs and framing elements to be rhetorical constructions that function together. In each phase of my analysis, I developed ideological themes from concepts emerging from the texts. I then approached my discussion of these findings from a perspective of Neo-Marxism, primarily using Gramsci’s (1971) critique of cultural hegemony to inform my conclusions. -

Zionist Raids Damage Kuwait Specialized Hospital in Gaza

SHAWWAL 8, 1442 AH THURSDAY, MAY 20, 2021 16 Pages Max 47º Min 27º 150 Fils Established 1961 ISSUE NO: 18438 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Pandemic triggering Longtime car fan Biden Chile’s large Palestinian Benzema recalled by France 8 orphan crisis in India 9 lives his electric dreams 15 community protests strikes 16 for Euro 2020 after 6-yr exile Zionist raids damage Kuwait Specialized Hospital in Gaza Protests continue in Kuwait despite attempts by MoI to ban gatherings By B Izzak and Agencies take place. The ministry had banned another gathering a few days ago, which prompted three GAZA/KUWAIT: The administration of the Kuwait opposition lawmakers to announce their intention Specialized Hospital in Gaza City said yesterday the to grill Interior Minister Sheikh Thamer Al-Sabah. hospital’s facilities were damaged by Zionist raids on The grilling has not yet been filed. The National Rafah in southern Gaza Strip. At dawn, some facili- Assembly will hold a special session next Sunday ties were damaged at Kuwait Specialized Hospital in to debate grillings against three ministers over Rafah governorate, administrative supervisor at the allegations of mismanagement and failure to hospital Talaat Barhoum said in a press statement. respect questions sent by lawmakers. The hospital was damaged after the Zionist Ten opposition MPs had requested the special occupation forces targeted a charity near the hos- session in order to avoid discussing the issue in a pital, which provides aid to the people of Rafah, he regular session, which the opposition is not said. -

Sustaining Urban Farming in 2019 Detroit

“We’re like an illegitimate child for the city”: Sustaining urban farming in 2019 Detroit Rémi Guillem Mémoire présenté pour le Master en Discipline : Sociologie Mention : Governing the Large Metropolis Directeur/ Directrice du mémoire : Sophie Dubuisson-Quellier 2018-2019 1 Summary 2 Foreword 3 General introduction 4 Introduction: What is the point of growing food when the house is burning? 4 Urban agriculture and Detroit: a literature review and our conceptual 6 positioning Methodology: Understanding urban farming through exchanges of gifts and 14 political attitudes Section 1: Reciprocity, conflicts and evidences of exchange 29 networks in Detroit 1. Two coexisting networks: grant and barter exchanges revealed 30 2. “Ce que donner veut dire”: conflicts and rules presiding exchanges 37 3. Two interrelated networks, two visions of giving 43 Section 2: Contentious definitions of city decline and urban 47 farming 1. The elites’ and the farmers’ coalition: fighting decline with a vision for 48 the city 2. Detroit Future city Framework and Urban Agriculture Ordinance 56 (2010-2013): contentious definitions of urban agriculture in-the-making Section 3: Urban Farming in shrinking cities: the margins of 69 markets 1. “True Detroit Hustle”: inequalities in farming inputs (land, financing) 70 and food sales opportunities 2. Urban farming movement: contestation and deformation of a market 77 General Conclusion 84 BiBliography 86 Annex-Methodology 95 Annex-Section 1 98 Annex-Section 2 100 Annex-Section 3 101 Tables of table/ Table of figures 104 Table of contents 104 2 Foreword Joel Sternfeld, 1987 “McLean, Virginia, December 1978” in American Prospects, Time Books: Houston Original: dye transfer print, National Gallery of Canada Although it would be impossible for me to personally thank all of the individuals who helped me make this dissertation project a reality, I would like to take a brief moment to acknowledge the contribution and support of the following people.