The Anti-Gang Initiative in Detroit: an Aggressive Enforcement Approach to Gangs Timothy S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here We Are at 500! the BRL’S 500 to Be Exact and What a Trip It Has Been

el Fans, here we are at 500! The BRL’s 500 to be exact and what a trip it has been. Imagibash 15 was a huge success and the action got so intense that your old pal the Teamster had to get involved. The exclusive coverage of that ppv is in this very issue so I won’t spoil it and give away the ending like how the ship sinks in Titanic. The Johnny B. Cup is down to just four and here are the representatives from each of the IWAR’s promotions; • BRL Final: Sir Gunther Kinderwacht (last year’s winner) • CWL Final: Jane the Vixen Red (BRL, winner of 2017 Unknown Wrestler League) • IWL Final: Nasty Norman Krasner • NWL Final: Ricky Kyle In one semi-final, we will see bitter rivals Kinderwacht and Red face off while in the other the red-hot Ricky Kyle will face the, well, Nasty Normal Krasner. One of these four will win The self-professed “Greatest Tag team wrestler the 4th Johnny B Cup and the results will determine the breakdown of the prizes. ? in the world” debuted in the NWL in 2012 and taunt-filled promos earned him many enemies. The 26th Marano Memorial is also down to the final 5… FIVE? Well since the Suburban Hell His “Teamster Challenge” offered a prize to any Savages: Agent 26 & Punk Rock Mike and Badd Co: Rick Challenger & Rick Riley went to a NWL rookie who could capture a Tag Team title draw, we will have a rematch. The winner will advance to face Sledge and Hammer who won with him, but turned ugly when he kept blaming the CWL bracket. -

Open Space and Recreation Plan Town of Rockport

OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN TOWN OF ROCKPORT 2019 ®Maps produced by Peter Van Demark using Maptitude GIS software Final Approval 7 October 2020 Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs Open Space and Recreation Committee: Lawrence Neal, Conservation Commission and Chair, Rob Claypool, Stephanie Cunningham, Tom Mikus, Rights of Way, Frederick H. “Ted” Tarr III, Peter Van Demark, Cartographer Open Space and Recreation Plan for the Town of Rockport 2019 - 2026 2 Open Space and Recreation Plan for the Town of Rockport 2019 - 2026 PROSPERITY FOLLOWS SERVICE PATHWAYS The Islanders had built along the shoreline leaving the center of the island almost virgin overgrown with trees and brush, an occasional open area here, a granite deposit there. Pathways cut through the terrain, offering a tourist hiker several choices. A new path is always an adventure. The first passage is more a reconnoiter concentrating on direction, orientation, markers and eventual destination. The second pass is leisurely and indulgent allowing time to appreciate the colors, odors, indigenous flora, local fauna, the special essence of the place. Approach a poem like a wooded path with secrets to impart, one reading will reveal her scheme, the second her heart. from Pathways by J.J. Coyle This plan is dedicated to Frederick H. “Ted” Tarr, III. Thank you for the pathways. Thank you for your service. 3 Open Space and Recreation Plan for the Town of Rockport 2019 - 2026 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................ -

Prohibition's Proving Ground: Automobile Culture and Dry

PROHIBITION’S PROVING GROUND: AUTOMOBILE CULTURE AND DRY ENFORCEMENT ON THE TOLEDO-DETROIT-WINDSOR CORRIDOR, 1913-1933 Joseph Boggs A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2019 Committee: Michael Brooks, Advisor Rebecca Mancuso © 2019 Joseph Boggs All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Michael Brooks, Advisor The rapid rise of an automobile culture in the 1910s and 20s provided ordinary North Americans greater mobility, freedom, privacy, and economic opportunity. Simultaneously, the United States and Canada witnessed a surge in “dry” sentiments and laws, culminating in the passage of the 18th Amendment and various provincial acts that precluded the outright sale of alcohol to the public. In turn, enforcement of prohibition legislation became more problematic due to society’s quick embracing of the automobile and bootleggers’ willingness to utilize cars for their illegal endeavors. By closely examining the Toledo-Detroit-Windsor corridor—a region known both for its motorcar culture and rum-running reputation—during the time period of 1913-1933, it is evident why prohibition failed in this area. Dry enforcers and government officials, frequently engaging in controversial policing tactics when confronting suspected motorists, could not overcome the distinct advantages that automobiles afforded to entrepreneurial bootleggers and the organized networks of criminals who exploited the transnational nature of the region. vi TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER I. AUTOMOBILITY ON THE TDW CORRIDOR ............................................... 8 CHAPTER II. MOTORING TOWARDS PROHIBITION ......................................................... 29 CHAPTER III. TEST DRIVE: DRY ENFORCEMENT IN THE EARLY YEARS .................. 48 The Beginnings of Prohibition in Windsor, 1916-1919 ............................................... -

10 Side Businesses You Didn't Know WWE Wrestlers Owned WWE

10 Side Businesses You Didn’t Know WWE Wrestlers Owned WWE Wrestlers make a lot of money each year, and some still do side jobs. Some use their strength and muscle to moonlight as bodyguards, like Sheamus and Brodus Clay, who has been a bodyguard for Snoop Dogg. And Paul Bearer was a funeral director in his spare time and went back to it full time after he retired until his death in 2012. And some of the previous jobs WWE Wrestlers have had are a little different as well; Steve Austin worked at a dock before he became a wrestler. Orlando Jordan worked for the U.S. Forest Service for the group that helps put out forest fires. The WWE’s Maven was a sixth- grade teacher before wrestling. Rico was a one of the American Gladiators before becoming a wrestler, for those who don’t know what the was, it was TV show on in the 90’s. That had strong men and woman go up against contestants; they had events that they had to complete to win prizes. Another profession that many WWE Wrestlers did before where a wrestler is a professional athlete. Kurt Angle competed at the 1996 Summer Olympics in freestyle wrestling and won a gold metal. Mark Henry also competed in that Olympics in weightlifting. Goldberg played for three years with the Atlanta Falcons. Junk Yard Dog and Lex Luger both played for the Green Bay Packers. Believe it or not but Macho Man Randy Savage played in the minor league Cincinnati Reds before he was telling the world “Oh Yeah.” Just like most famous people they had day jobs before they because professional wrestlers. -

MIAA/MSAA CERTIFIED COACHES First Last School Kerin Biggins

MIAA/MSAA CERTIFIED COACHES First Last School Kerin Biggins Abby Kelley Foster Charter School Patrick Biggins Abby Kelley Foster Charter School Jennifer Bridgers Abby Kelley Foster Charter School Cheryl Corey Abby Kelley Foster Charter School Cheryl Corey Abby Kelley Foster Charter School Dave Ferraro Abby Kelley Foster Charter School Rebecca Gamble Abby Kelley Foster Charter School Chris Girardi Abby Kelley Foster Charter School Tamara Hampton Abby Kelley Foster Charter School Matt Howard Abby Kelley Foster Charter School Jamie LaFlash Abby Kelley Foster Charter School Mathew Lemire Abby Kelley Foster Charter School Francis Martell Abby Kelley Foster Charter School Grace Milner Abby Kelley Foster Charter School Brian Morse Abby Kelley Foster Charter School Michael Penney Abby Kelley Foster Charter School Henry Zussman Abby Kelley Foster Charter School Matthew MacLean Abington High School Lauren Pietrasik Abington High School Jason Brown Abington High School Michael Bruning Abington High School Matt Campbell Abington High School Kate Casey Abington High School Kristin Gerhart Abington High School Jennifer Krouse Abington High School Chris Madden Abington High School John McGInnis Abington High School Dan Norton Abington High School Steven Perakslis Abington High School Scott Pifer Abington High School Thomas Rogers Abington High School Peter Serino Abington High School James Smith Abington High School Judy Hamilton Abington Public Schools Gary Abrams Academy of Notre Dame Wally Armstrong Academy of Notre Dame Kevin Bailey Academy of Notre -

San Diego County Treasurer-Tax Collector 2019-2020 Returned Property Tax Bills

SAN DIEGO COUNTY TREASURER-TAX COLLECTOR 2019-2020 RETURNED PROPERTY TAX BILLS TO SEARCH, PRESS "CTRL + F" CLICK HERE TO CHANGE MAILING ADDRESS PARCEL/BILL OWNER NAME 8579002100 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8579002104 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8579002112 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8679002101 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8679002105 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8679002113 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8779002102 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8779002106 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8779002114 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8879002103 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8879002107 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 8879002115 11-11 GIFT TRUST 04-01-96 5331250200 1141 LAGUNA AVE L L C 2224832400 1201 VIA RAFAEL LTD 3172710300 12150 FLINT PLACE LLC 2350405100 1282 PACIFIC OAKS LLC 4891237400 1360 E MADISON AVENUE L L C 1780235100 138 SUN VILLA CT LLC 8894504458 138 SUN VILLA CT LLC 2222400700 1488 SAN PABLO L L C 1300500500 15195 HWY 76 TRUST 04-084 1473500900 152 S MYERS LLC 4230941300 1550 GARNET LLC 2754610900 15632 POMERADO ROAD L L C 1678 COUNTRY CLUB DR ESCONDIDO CA 92029 TRUST 05-07- 2325114700 18 1678 COUNTRY CLUB DR ESCONDIDO CA 92029 TRUST 05-07- 8894616148 18 2542212300 1697A LA COSTA MEADOWS L L C 2542212400 1697A LA COSTA MEADOWS L L C 6461901900 1704 CACTUS ROAD LLC 5333021200 1750 FIFTH AVENUE L L C 2542304001 180 PHOEBE STREET LLC 5392130600 1815-19 GRANADA AVENUE LLC 5392130700 1815-19 GRANADA AVENUE LLC 2643515400 18503 CALLE LA SERRA L L C 2263601300 1991 TRUST 12-02-91 AND W J K FAMILY LTD PARTNERSHIP 5650321400 1998 ENG FAMILY L L C 5683522300 1998 ENG FAMILY L L -

Marriage Record Index 1922-1938 Images Can Be Accessed in the Indiana Room

Marriage Record Index 1922-1938 Images can be accessed in the Indiana Room. Call (812)949-3527 for more information. Groom Bride Marriage Date Image Aaron, Elza Antle, Marion 8/12/1928 026-048 Abbott, Charles Ruby, Hallie June 8/19/1935 030-580 Abbott, Elmer Beach, Hazel 12/9/1922 022-243 Abbott, Leonard H. Robinson, Berta 4/30/1926 024-324 Abel, Oscar C. Ringle, Alice M. 1/11/1930 027-067 Abell, Lawrence A. Childers, Velva 4/28/1930 027-154 Abell, Steve Blakeman, Mary Elizabeth 12/12/1928 026-207 Abernathy, Pete B. Scholl, Lorena 10/15/1926 024-533 Abram, Howard Henry Abram, Elizabeth F. 3/24/1934 029-414 Absher, Roy Elgin Turner, Georgia Lillian 4/17/1926 024-311 Ackerman, Emil Becht, Martha 10/18/1927 025-380 Acton, Dewey Baker, Mary Cathrine 3/17/1923 022-340 Adam, Herman Glen Harpe, Mary Allia 4/11/1936 031-273 Adam, Herman Glenn Hinton, Esther 8/13/1927 025-282 Adams, Adelbert Pope, Thelma 7/14/1927 025-255 Adams, Ancil Logan, Jr. Eiler, Lillian Mae 4/8/1933 028-570 Adams, Cecil A. Johnson, Mary E. 12/21/1923 022-706 Adams, Crozier E. Sparks, Sarah 4/1/1936 031-250 Adams, Earl Snook, Charlotte 1/5/1935 030-250 Adams, Harry Meyer, Lillian M. 10/21/1927 025-376 Adams, Herman Glen Smith, Hazel Irene 2/28/1925 023-502 Adams, James O. Hallet, Louise M. 4/3/1931 027-476 Adams, Lloyd Kirsch, Madge 6/7/1932 028-274 Adams, Robert A. -

Illicit Economies in the Detroit- Windsor Borderland, 1945-1960

Ambassadors of Pleasure: Illicit Economies in the Detroit- Windsor Borderland, 1945-1960 by Holly Marie Karibo A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy History Department University of Toronto © Copyright by Holly Karibo (2012) Ambassadors of Pleasure: Illicit Economies in the Detroit-Windsor Borderland, 1945-1960 Holly Karibo Doctor of Philosophy History Department University of Toronto 2012 Abstract “Ambassadors of Pleasure” examines the social and cultural history of ‘sin’ in the Detroit-Windsor border region during the post-World War II period. It employs the interrelated frameworks of “borderlands” and “vice” in order to identify the complex ways in which illicit economies shaped—and were shaped by—these border cities. It argues that illicit economies served multiple purposes for members of local borderlands communities. For many downtown residents, vice industries provided important forms of leisure, labor, and diversion in cities undergoing rapid changes. Deeply rooted in local working-class communities, prostitution and heroin economies became intimately intertwined in the daily lives of many local residents who relied on them for both entertainment and income. For others, though, anti-vice activities offered a concrete way to engage in what they perceived as community betterment. Fighting the immoral influences of prostitution and drug use was one way some residents, particularly those of the middle class, worked to improve their local communities in seemingly tangible ways. These II struggles for control over vice economies highlight the ways in which shifting meanings of race, class, and gender, growing divisions between urban centers and suburban regions, and debates over the meaning of citizenship evolved in the urban borderland. -

15E5 Ssgt Selects by Alpha

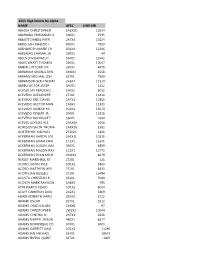

15E5 SSgt Selects by Alpha NAME AFSC LINE-NR ABADIA CHRISTOPHER 2A5X2D 10234 ABARAWA EMMANUEL K 3S0X1 1595 ABBOTT DANIEL PATR 2A7X3 10224 ABDULLAH MALIZIO J 3P0X1 7420 ABENDROTH MARIE CH 00XXX 11386 ABESAMIS CHAMAL JA 2S0X1 44 ABLES LOVIEANGELO 3S0X1 11062 ABLES WYATT THOMAS 2S0X1 10007 ABNER CLIFFORD LEE 3P0X1 4479 ABRAHAM SHARLA DEN 3M0X1 3558 ABRAMS MICHAEL JOH 3E7X1 7500 ABRAMSON SETH NEWM 2A6X4 11510 ABREU VICTOR JOSEP 3P0X1 1412 ACASIO JAY PEROCHO 1P0X1 8032 ACEVEDO ALEXANDER 2T3X1 11416 ACEVEDO ERIC DAVID 2A7X1 12965 ACEVEDO HECTOR MAN 1A0X1 11303 ACEVEDO JANIECE PA 3D0X1 13070 ACEVEDO ROBERT JR 2F0X1 11918 ACEVEDO RODRIGUEZ 3S0X1 2680 ACEVES ULYSSES ALE 2A3X4A 1056 ACHESON SHON THOMA 2A8X2B 5382 ACHTERHOF MICHAEL 2T3X2C 1821 ACKERMAN AARON JOS 2A3X3L 10231 ACKERMAN ADAM CRAI 1C1X1 11641 ACKERMAN LOGAN JAM 3P0X1 8889 ACKERMAN MASON RAY 1C3X1 12772 ACKERMAN RYAN MICH 2M0X3 8079 ACKLEY MARSHALL RY 2T2X1 321 ACORD JUSTIN KYLE 3D1X2 5960 ACORD MATTHEW WILL 2T2X1 5433 ACORN IAN RUSSELL 2T1X1 12494 ACOSTA CHRISTIAN R 3E3X1 7080 ACOSTA MARK RAYMON 2A6X2 495 ACRI MARCO ELIGIO 3D1X2 8009 ACUFF CAMERON DAVI 2A2X1 6869 ADAIR KENNETH HARO 3D0X2 8722 ADAME OSCAR 3E7X1 1512 ADAMS CHAD KALANI 2A6X6 97 ADAMS CHRISTOPHER 2W1X1 10004 ADAMS CYNTHIA N 2A7X3 2658 ADAMS DARRYL JEMON 4B0X1 5627 ADAMS DOMINIQUE CO 3P0X1 3003 ADAMS GARRETT DAVI 3D1X3 11290 ADAMS IAN MICHAEL 3E4X1 10643 ADAMS IRVING QUINT 3E7X1 3407 ADAMS JAMES COLBY 2T3X1 2522 ADAMS JASON ROBERT 1U0X1 7795 ADAMS JOSEPH AARON 2A9X2E 2595 ADAMS KEITH JR 3P0X1 2642 ADAMS KYLE EDWARD 3D0X2 -

Jefferson Co Corrections Inmate Roster 9/02/21 20:00

JEFFERSON CO CORRECTIONS INMATE ROSTER 9/28/21 8:00 PAGE 1 ALL DATA SUBJECT TO CHANGE. BOND/FEES MUST BE PAID WITH EXACT CASH. CALL 409-726-2540 FOR DETAILS. NAME AGE R/S OFFENSE ARRESTED BOND WARRANT -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ABRAHAM DOMINQUE 10/12/20 18:10 BY BPD 18 BM ROBBERY-AGGRAVATED 250,000.00 35767 OF FAILURE TO APPEAR 31158 C -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ABSHIRE ALICIA ANN 9/26/21 16:50 BY PAPD 34 WF FRAUD-DEST,REMOVE WRITING 2,000.00 MA -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ABSHIRE LACHRISHA RENAE 5/13/20 18:00 BY PAPD 33 WF MURDER 300,000.00 34516 OF FAILURE TO APPEAR 724244 C THEFT-CLASS B 20,000.00 321852 A OM THEFT SJ 10,000.00 34175 A OS -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ACKLIN JAZE 1/29/21 14:27 BY JCSO 20 WM POSS C/S PEN GRP 1 100,000.00 32625 M PF ROBBERY-AGGRAVATED 75,000.00 36033 OF -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ADAMS BLAKE EDWARD 8/03/21 12:30 BY JCSO 35 WM POSS C/S PEN GRP 2 SJ 100,000.00 37593 B OS -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- AGER GREGORY JOSEPH 6/05/21 13:36 BY BPD 28 BM MURDER 1,250,000.00 37766 OF POSS C/S PEN GRP 1 30,000.00 38112 OF POSS C/S PEN GRP 1 20,000.00 38113 OF POSS C/S PEN GRP 1 SJ 10,000.00 38114 OS -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- AGUILAR HERMAN DARINEL 10/06/20 16:49 BY JCSO 32 WM CONTINUOUS SEX ABUSE CHILD 100,000.00 35423 OF INDECENCY- WITH CHILD 50,000.00 35424 OF ASSLT-SEXUAL-CHILD 50,000.00 35425 OF HOLD FOR I.C.E. -

Crime and Poverty in Detroit: a Cross-Referential Critical Analysis of Ideographs and Framing

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 4-11-2014 Crime And Poverty In Detroit: A Cross-Referential Critical Analysis Of Ideographs And Framing Jacob Jerome Nickell Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Nickell, Jacob Jerome, "Crime And Poverty In Detroit: A Cross-Referential Critical Analysis Of Ideographs And Framing" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 167. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/167 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CRIME AND POVERTY IN DETROIT: A CROSS-REFERENTIAL CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF IDEOGRAPHS AND FRAMING Jacob J. Nickell 135 Pages May 2014 This thesis examines how the relationship between crime and poverty is rhetorically constructed within the news media. To this end, I investigate the content of twelve news articles, published online, that offered coverage of crime in the city of Detroit, Michigan. I employ three methods in my criticism of these texts: ideographic analysis, critical framing analysis, and an approach that considers ideographs and framing elements to be rhetorical constructions that function together. In each phase of my analysis, I developed ideological themes from concepts emerging from the texts. I then approached my discussion of these findings from a perspective of Neo-Marxism, primarily using Gramsci’s (1971) critique of cultural hegemony to inform my conclusions. -

May 2, 2021 Texas Peace Officers' Memorial & Candlelight Vigil

Texas Peace Officers’ Memorial & Candlelight Vigil HH NN OO EE N LL O LL R AA IN ’ FF G TEXXAASS’ MAY 2, 2021 2 Table of Contents Texas Peace Officers’ Memorial & Candlelight Vigil 4 Thin Blue Line Poem 5 Roll Call of Officers | 2019 - 2020 6–8 Roll Call of Officers - COVID | 2020 9–10 Special Thanks 9 Officers’ Names Chronologically by Department 14 Panel Locator Map 88 3 Texas Peace Officers’ Memorial & Candlelight Vigil - Sunday, May 2, 2021 Memorial Procession Keynote Address Honor Guards & Law Enforcement Units The Honorable Greg Abbott, Sgt. Tim Kresta, Austin Police Department Governor of Texas Call to Order Roll Call of Officers Senior Police Officer Ricky Hollis, The Honorable James White, Austin Police Department Chairman, House Committee on Homeland Security and Public Safety National Anthem Sgt. Ray Polk, Presentation of Medals & Resolutions Arlington Police Department Riderless Horse Invocation Lubbock Police Department Chaplain Vince Johnson Houston Police Department Twenty-One Gun Salute Introduction of Emcee Various Texas Law Enforcement Agencies Senior Police Officer Ricky Hollis, Austin Police Department Taps McAllen Police Department Honor Guard Welcome Remarks Austin Police Department Honor Guard Troy Kimmel, KOKE FM Flyover Austin Police Department Lighting of the Ceremonial Candle Kaden Senter, Benediction Son of Nassau Bay Sgt. Kaila Marie Sullivan Chaplain Greg Long, Laying of the Wreath Elgin Police Department McAllen Police Department Honor Guard Song Song Granger Smith Granger Smith Thin Blue Line Guest Speakers “Amazing Grace” Lt. Marvin Ryals, CLEAT President Bagpipers, Combined Pipe & Drum Corps Lt. Thomas Brown, Movement of Wreath to Memorial Site TMPA President McAllen Police Department Honor Guard Valerie Zamarripa, Mother of Fallen Dallas Police Officer Retire the Colors Patrick Zamarripa | EOW: July 7, 2016 The Honorable Dan Patrick, Dismissal Lt.