Copyright by Victoria Campbell Hill 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Four Sociologies, Multiple Roles

The British Journal of Sociology 2005 Volume 56 Issue 3 Four sociologies, multiple roles Stella R. Quah The current American and British debate on public sociology introduced by Michael Burawoy in his 2004 ASA Presidential Address (Burawoy 2005) has inadvertently brought to light once again, one exciting but often overlooked aspect of our discipline: its geographical breadth.1 Sociology is present today in more countries around the world than ever before. Just as in the case of North America and Europe, Sociology’s presence in the rest of the world is manifested in many ways but primarily through the scholarly and policy- relevant work of research institutes, academic departments and schools in universities; through the training of new generations of sociologists in univer- sities; and through the work of individual sociologists in the private sector or the civil service. Michael Burawoy makes an important appeal for public sociology ‘not to be left out in the cold but brought into the framework of our discipline’ (2005: 4). It is the geographical breadth of Sociology that provides us with a unique vantage point to discuss his appeal critically. And, naturally, it is the geo- graphical breadth of sociology that makes Burawoy’s Presidential Address to the American Sociological Association relevant to sociologists outside the USA. Ideas relevant to all sociologists What has Michael Burawoy proposed that is most relevant to sociologists beyond the USA? He covers such an impressive range of aspects of the dis- cipline that it is not possible to address all of them here. Thus, thinking in terms of what resonates most for sociologists in different locations throughout the geographical breadth of the discipline, I believe his analytical approach and his call for integration deserve special attention. -

The Revival of Economic Sociology

Chapter 1 The Revival of Economic Sociology MAURO F. G UILLEN´ , RANDALL COLLINS, PAULA ENGLAND, AND MARSHALL MEYER conomic sociology is staging a comeback after decades of rela- tive obscurity. Many of the issues explored by scholars today E mirror the original concerns of the discipline: sociology emerged in the first place as a science geared toward providing an institutionally informed and culturally rich understanding of eco- nomic life. Confronted with the profound social transformations of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the founders of so- ciological thought—Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim, Max Weber, Georg Simmel—explored the relationship between the economy and the larger society (Swedberg and Granovetter 1992). They examined the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services through the lenses of domination and power, solidarity and inequal- ity, structure and agency, and ideology and culture. The classics thus planted the seeds for the systematic study of social classes, gender, race, complex organizations, work and occupations, economic devel- opment, and culture as part of a unified sociological approach to eco- nomic life. Subsequent theoretical developments led scholars away from this originally unified approach. In the 1930s, Talcott Parsons rein- terpreted the classical heritage of economic sociology, clearly distin- guishing between economics (focused on the means of economic ac- tion, or what he called “the adaptive subsystem”) and sociology (focused on the value orientations underpinning economic action). Thus, sociologists were theoretically discouraged from participating 1 2 The New Economic Sociology in the economics-sociology dialogue—an exchange that, in any case, was not sought by economists. It was only when Parsons’s theory was challenged by the reality of the contentious 1960s (specifically, its emphasis on value consensus and system equilibration; see Granovet- ter 1990, and Zelizer, ch. -

Social Theory's Essential Texts

Conference Information Features • Znaniecki Conference in Poland • The Essential Readings in Theory • Miniconference in San Francisco • Where Can a Student Find Theory? THE ASA July 1998 THEORY SECTION NEWSLETTER Perspectives VOLUME 20, NUMBER 3 From the Chair’s Desk Section Officers How Do We Create Theory? CHAIR By Guillermina Jasso Guillermina Jasso s the spring semester draws to a close, and new scholarly energies are every- where visible, I want to briefly take stock of sociological theory and the CHAIR-ELECT Theory Section. It has been a splendid privilege to watch the selflessness Janet Saltzman Chafetz A and devotion with which section members nurture the growth of sociological theory and its chief institutional steward, the Theory Section. I called on many of you to PAST CHAIR help with section matters, and you kindly took on extra burdens, many of them Donald Levine thankless except, sub specie aeternitatis, insofar as they play a part in advancing socio- logical theory. The Theory Prize Committee, the Shils-Coleman Prize Committee, SECRETARY-TREASURER the Nominations Committee, and the Membership Committee have been active; the Peter Kivisto newsletter editor has kept us informed; the session organizers have assembled an impressive array of speakers and topics. And thus, we can look forward to our COUNCIL meeting in August as a time for intellectual consolidation and intellectual progress. Keith Doubt Gary Alan Fine The section program for the August meetings includes one regular open session, one Stephen Kalberg roundtables session, and the three-session miniconference, entitled “The Methods Michele Lamont of Theoretical Sociology.” Because the papers from the miniconference are likely to Emanuel Schegloff become the heart of a book, I will be especially on the lookout for discussion at the miniconference sessions that could form the basis for additional papers or discus- Steven Seidman sion in the volume. -

And the CONCEPT of SOCIAL PROGRESS by Paul Jones Hebard

Lester Frank Ward and the concept of social progress Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Hebard, Paul Jones, 1908- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 21:56:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/553423 L E S T E R FRANK WARD and THE CONCEPT OF SOCIAL PROGRESS by Paul Jones Hebard A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of Economics, Sociology and Business administration in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of arts in the Graduate College University of Arizona 1939 dxy). 2- TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I. INTRODUCTION .................... 1 II, BIOGRAPHY OF LESTER FRANK WARD • . 5 III. SOCIAL ACHIEVEMENT THROUGH SOCIETAL DEVELOPMENT......................... 13 A. The Development of Man B. The social Forces C. The Dynamic Principles IV. SOCIALIZATION OF ACHIEVEMENT .... 29 a . Social Regulation B. Social Invention C. Social Appropriation Through Education D. Attractive Legislation B. Sociooracy F. Eugenics, Euthenics, Eudemics V. CRITICISM........................... 70 VI. CONCLUSION......................... 85 BIBLIOGRAPHY...................... 8? 1 2 2 6 5 3 CHAPTER I IMTROBOOTIOH The notion of progress has been the souree of mueh dis cussion since the time of Aristotle, but, only during the last three hundred years, has progress been considered an 1 achievement possible to man. In this sense it is a concept which has developed primarily in the vrostern world. -

Constructing an Emerging Field of Sociology Eddie Hartmann, Potsdam University

DOI: 10.4119/UNIBI/ijcv.623 IJCV: Vol. 11/2017 Violence: Constructing an Emerging Field of Sociology Eddie Hartmann, Potsdam University Vol. 11/2017 The IJCV provides a forum for scientific exchange and public dissemination of up-to-date scientific knowledge on conflict and violence. The IJCV is independent, peer reviewed, open access, and included in the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) as well as other relevant databases (e.g., SCOPUS, EBSCO, ProQuest, DNB). The topics on which we concentrate—conflict and violence—have always been central to various disciplines. Con- sequently, the journal encompasses contributions from a wide range of disciplines, including criminology, econom- ics, education, ethnology, history, political science, psychology, social anthropology, sociology, the study of reli- gions, and urban studies. All articles are gathered in yearly volumes, identified by a DOI with article-wise pagination. For more information please visit www.ijcv.org Author Information: Eddie Hartmann, Potsdam University [email protected] Suggested Citation: APA: Hartmann, E. (2017). Violence: Constructing an Emerging Field of Sociology. International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 11, 1-9. doi: 10.4119/UNIBI/ijcv.623 Harvard: Hartmann, Eddie. 2017. Violence: Constructing an Emerging Field of Sociology. International Journal of Conflict and Violence 11:1-9. doi: 10.4119/UNIBI/ijcv.623 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives License. ISSN: 1864–1385 IJCV: Vol. 11/2017 Hartmann: Violence: Constructing an Emerging Field of Sociology 1 Violence: Constructing an Emerging Field of Sociology Eddie Hartmann, Potsdam University @ Recent research in the social sciences has explicitly addressed the challenge of bringing violence back into the center of attention. -

Alice Rossi (1922-2009): Feminist Scholar and an Ardent Activist

Volume 38 • Number 1 • January 2010 Alice Rossi (1922-2009): Feminist Scholar and an Ardent Activist by Jay Demerath, Naomi Gerstel, Harvard, the University of were other honors too: inside Michael Lewis, University of Chicago, and John Hopkins The Ernest W. Burgess Massachusetts - Amherst as a “research associate”—a Award for Distinguished position often used at the Research on the Family lice S. Rossi—the Harriet time for academic women (National Council of ASA’s 2010 Election Ballot Martineau Professor of Sociology 3 A married to someone in Family Relations, 1996); Find out the slate of officer and Emerita at the University of the same field. She did not the Commonwealth Award Massachusetts - Amherst, a found- committee candidates for the receive her first tenured for a Distinguished Career ing board member of the National 2010 election. appointment until 1969, in Sociology (American Organization for Women (NOW) Alice Rossi (1922-2009) when she joined the faculty Sociological Association, (1966-70), first president of at Goucher College, and her first 1989); elected American Academy of August 2009 Council Sociologists for Women in Society 5 appointment to a graduate depart- Arts and Sciences Fellow (1986); and Highlights (1971-72), and former president of the ment did not come until 1974, honorary degrees from six colleges Key decisions include no change American Sociological Association when she and her husband, Peter H. and universities. in membership dues, but (1982-83)—died of pneumonia on Rossi, moved to the University of As an original thinker, Alice man- subscription rates see a slight November 3, 2009, in Northampton, Massachusetts-Amherst as Professors aged to combine her successful activ- Massachusetts. -

![HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] Nachrichten Von Heute](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8672/how-black-is-black-metal-journalismus-nachrichten-von-heute-488672.webp)

HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] Nachrichten Von Heute

HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] nachrichten von heute Kevin Coogan - Lords of Chaos (LOC), a recent book-length examination of the “Satanic” black metal music scene, is less concerned with sound than fury. Authors Michael Moynihan and Didrik Sederlind zero in on Norway, where a tiny clique of black metal musicians torched some churches in 1992. The church burners’ own place of worship was a small Oslo record store called Helvete (Hell). Helvete was run by the godfather of Norwegian black metal, 0ystein Aarseth (“Euronymous”, or “Prince of Death”), who first brought black metal to Norway with his group Mayhem and his Deathlike Silence record label. One early member of the movement, “Frost” from the band Satyricon, recalled his first visit to Helvete: I felt like this was the place I had always dreamed about being in. It was a kick in the back. The black painted walls, the bizarre fitted out with inverted crosses, weapons, candelabra etc. And then just the downright evil atmosphere...it was just perfect. Frost was also impressed at how talented Euronymous was in “bringing forth the evil in people – and bringing the right people together” and then dominating them. “With a scene ruled by the firm hand of Euronymous,” Frost reminisced, “one could not avoid a certain herd-mentality. There were strict codes for what was accept- ed.” Euronymous may have honed his dictatorial skills while a member of Red Ungdom (Red Youth), the youth wing of the Marxist/Leninist Communist Workers Party, a Stalinist/Maoist outfit that idolized Pol Pot. All who wanted to be part of black metal’s inner core “had to please the leader in one way or the other.” Yet to Frost, Euronymous’s control over the scene was precisely “what made it so special and obscure, creating a center of dark, evil energies and inspiration.” Lords of Chaos, however, is far less interested in Euronymous than in the man who killed him, Varg Vikemes from the one-man group Burzum. -

TAZ, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism.Pdf

T. A. Z. The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism By Hakim Bey Autonomedia Anti-copyright, 1985, 1991. May be freely pirated & quoted-- the author & publisher, however, would like to be informed at: Autonomedia P. O. Box 568 Williamsburgh Station Brooklyn, NY 11211-0568 Book design & typesetting: Dave Mandl HTML version: Mike Morrison Printed in the United States of America Part 1 T. A. Z. The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism By Hakim Bey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS CHAOS: THE BROADSHEETS OF ONTOLOGICAL ANARCHISM was first published in 1985 by Grim Reaper Press of Weehawken, New Jersey; a later re-issue was published in Providence, Rhode Island, and this edition was pirated in Boulder, Colorado. Another edition was released by Verlag Golem of Providence in 1990, and pirated in Santa Cruz, California, by We Press. "The Temporary Autonomous Zone" was performed at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics in Boulder, and on WBAI-FM in New York City, in 1990. Thanx to the following publications, current and defunct, in which some of these pieces appeared (no doubt I've lost or forgotten many--sorry!): KAOS (London); Ganymede (London); Pan (Amsterdam); Popular Reality; Exquisite Corpse (also Stiffest of the Corpse, City Lights); Anarchy (Columbia, MO); Factsheet Five; Dharma Combat; OVO; City Lights Review; Rants and Incendiary Tracts (Amok); Apocalypse Culture (Amok); Mondo 2000; The Sporadical; Black Eye; Moorish Science Monitor; FEH!; Fag Rag; The Storm!; Panic (Chicago); Bolo Log (Zurich); Anathema; Seditious Delicious; Minor Problems (London); AQUA; Prakilpana. Also, thanx to the following individuals: Jim Fleming; James Koehnline; Sue Ann Harkey; Sharon Gannon; Dave Mandl; Bob Black; Robert Anton Wilson; William Burroughs; "P.M."; Joel Birroco; Adam Parfrey; Brett Rutherford; Jake Rabinowitz; Allen Ginsberg; Anne Waldman; Frank Torey; Andr Codrescu; Dave Crowbar; Ivan Stang; Nathaniel Tarn; Chris Funkhauser; Steve Englander; Alex Trotter. -

1 Copyright 2004 by the American Sociological Association Section on the History of Sociology

A BRIEF CENTENNIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF RESOURCES ON THE HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL SOCIETY/ASSOCIATION1 Compiled by the Centennial Bibliography Project Committee2 American Sociological Association Section on the History of Sociology ELEBRATING THE CENTENNIAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION provides the ritual occasion and reinforces the intellectual rationale for collectively exploring our Cprofessional and organizational roots. To guide us on our way, we have compiled a brief bibliography of relevant materials and exemplars that explicate the early history of the American Sociological Society and – to some degree – its subsequent evolution (the line separating “history” from “current events” is not always easily drawn). Practicing extreme parsimony, we have intentionally excluded literally thousands of otherwise important and instructive published works that focus primarily on specific departments of sociology, the ideas and accomplishments of individual sociologists, the development of sociological theories, the general intellectual history of the discipline as a whole, and myriad other matters of obvious historical and disciplinary interest. We hasten to add, however, that the structure and practical scope of a much more inclusive bibliography is now under consideration and is soon to be implemented. In the interim, we provide here a small down payment: a narrowly defined set of references for selected articles – and still fewer monographs – that specifically address, in various ways, the founding era and subsequent evolution of the American Sociological Society as a professional organization. To these citations, we add lists of relevant journals, abstracts, indexes and databases, and append the locations of archival deposits for the first ten presidents of the American Sociological Society, with the hope of encouraging ever more scholarship on the early history of the ASS/ASA per se.3 Corrections and suggested additions to this bibliography, focused specifically on the history of the ASS/ASA, are welcomed by the committee. -

Rethinking Burawoy's Public Sociology: a Post-Empiricist Critique." in the Handbook of Public Sociology, Edited by Vincent Jeffries, 47-70

Morrow, Raymond A. "Rethinking Burawoy's Public Sociology: A Post-Empiricist Critique." In The Handbook of Public Sociology, edited by Vincent Jeffries, 47-70. Lantham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2009. 3 Rethinking Burawoy’s Public Sociology: A Post-Empiricist Reconstruction Raymond A. Morrow Following Michael Burawoy’s ASA presidential address in August 2004, “For Public Sociology,” an unprecedented international debate has emerged on the current state and future of sociology (Burawoy 2005a). The goal here will be to provide a stock-taking of the resulting commentary that will of- fer some constructive suggestions for revising and reframing the original model. The central theme of discussion will be that while Burawoy’s mani- festo is primarily concerned with a plea for the institutionalization of pub- lic sociology, it is embedded in a very ambitious social theoretical frame- work whose full implications have not been worked out in sufficient detail (Burawoy 2005a). The primary objective of this essay will be to highlight such problems in the spirit of what Saskia Sassen calls “digging” to “detect the lumpiness of what seems an almost seamless map” (Sassen 2005:401) and to provide suggestions for constructive alternatives. Burawoy’s proposal has enjoyed considerable “political” success: “Bura- woy’s public address is, quite clearly, a politician’s speech—designed to build consensus and avoid ruffling too many feathers” (Hays 2007:80). As Patricia Hill Collins puts it, the eyes of many students “light up” when the schema is presented: “There’s the aha factor at work. They reso- nate with the name public sociology. Wishing to belong to something bigger than themselves” (Collins 2007:110–111). -

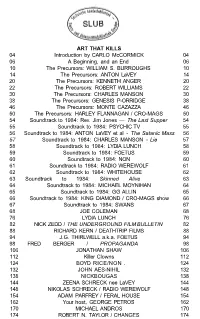

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO Mccormick 04 06 a Beginning, and an End 06 10 the Precursors: WILLIAM S

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO McCORMICK 04 06 A Beginning, and an End 06 10 The Precursors: WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS 10 14 The Precursors: ANTON LaVEY 14 20 The Precursors: KENNETH ANGER 20 22 The Precursors: ROBERT WILLIAMS 22 30 The Precursors: CHARLES MANSON 30 38 The Precursors: GENESIS P-ORRIDGE 38 46 The Precursors: MONTE CAZAZZA 46 50 The Precursors: HARLEY FLANNAGAN / CRO-MAGS 50 54 Soundtrack to 1984: Rev. Jim Jones — The Last Supper 54 55 Soundtrack to 1984: PSYCHIC TV 55 56 Soundtrack to 1984: ANTON LaVEY et al - The Satanic Mass 56 57 Soundtrack to 1984: CHARLES MANSON - Lie 57 58 Soundtrack to 1984: LYDIA LUNCH 58 59 Soundtrack to 1984: FOETUS 59 60 Soundtrack to 1984: NON 60 61 Soundtrack to 1984: RADIO WEREWOLF 61 62 Soundtrack to 1984: WHITEHOUSE 62 63 Soundtrack to 1984: Skinned Alive 63 64 Soundtrack to 1984: MICHAEL MOYNIHAN 64 65 Soundtrack to 1984: GG ALLIN 65 66 Soundtrack to 1984: KING DIAMOND / CRO-MAGS show 66 67 Soundtrack to 1984: SWANS 67 68 JOE COLEMAN 68 76 LYDIA LUNCH 76 82 NICK ZEDD / THE UNDERGROUND FILM BULLETIN 82 88 RICHARD KERN / DEATHTRIP FILMS 88 94 J.G. THIRLWELL a.k.a. FOETUS 94 98 FRED BERGER / PROPAGANDA 98 106 JONATHAN SHAW 106 112 Killer Clowns 112 124 BOYD RICE/NON . 124 132 JOHN AES-NIHIL 132 138 NICKBOUGAS 138 144 ZEENA SCHRECK nee LaVEY 144 148 NIKOLAS SCHRECK / RADIO WEREWOLF 148 154 ADAM PARFREY / FERAL HOUSE 154 162 Your host, GEORGE PETROS 162 170 MICHAEL ANDROS 170 174 ROBERT N. -

Centennial Bibliography on the History of American Sociology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 2005 Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology Michael R. Hill [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Hill, Michael R., "Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology" (2005). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 348. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/348 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Hill, Michael R., (Compiler). 2005. Centennial Bibliography of the History of American Sociology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association. CENTENNIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY ON THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN SOCIOLOGY Compiled by MICHAEL R. HILL Editor, Sociological Origins In consultation with the Centennial Bibliography Committee of the American Sociological Association Section on the History of Sociology: Brian P. Conway, Michael R. Hill (co-chair), Susan Hoecker-Drysdale (ex-officio), Jack Nusan Porter (co-chair), Pamela A. Roby, Kathleen Slobin, and Roberta Spalter-Roth. © 2005 American Sociological Association Washington, DC TABLE OF CONTENTS Note: Each part is separately paginated, with the number of pages in each part as indicated below in square brackets. The total page count for the entire file is 224 pages. To navigate within the document, please use navigation arrows and the Bookmark feature provided by Adobe Acrobat Reader.® Users may search this document by utilizing the “Find” command (typically located under the “Edit” tab on the Adobe Acrobat toolbar).