Transcript a Pinewood Dialogue with Chuck Jones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

Here Comes Television

September 1997 Vol. 2 No.6 HereHere ComesComes TelevisionTelevision FallFall TVTV PrPrevieweview France’France’ss ExpandingExpanding ChannelsChannels SIGGRAPHSIGGRAPH ReviewReview KorKorea’ea’ss BoomBoom DinnerDinner withwith MTV’MTV’ss AbbyAbby TTerkuhleerkuhle andand CTW’CTW’ss ArleneArlene SherShermanman Table of Contents September 1997 Vol. 2, . No. 6 4 Editor’s Notebook Aah, television, our old friend. What madness the power of a child with a remote control instills in us... 6 Letters: [email protected] TELEVISION 8 A Conversation With:Arlene Sherman and Abby Terkuhle Mo Willems hosts a conversation over dinner with CTW’s Arlene Sherman and MTV’s Abby Terkuhle. What does this unlikely duo have in common? More than you would think! 15 CTW and MTV: Shorts of Influence The impact that CTW and MTV has had on one another, the industry and beyond is the subject of Chris Robinson’s in-depth investigation. 21 Tooning in the Fall Season A new splash of fresh programming is soon to hit the airwaves. In this pivotal year of FCC rulings and vertical integration, let’s see what has been produced. 26 Saturday Morning Bonanza:The New Crop for the Kiddies The incurable, couch potato Martha Day decides what she’s going to watch on Saturday mornings in the U.S. 29 Mushrooms After the Rain: France’s Children’s Channels As a crop of new children’s channels springs up in France, Marie-Agnès Bruneau depicts the new play- ers, in both the satellite and cable arenas, during these tumultuous times. A fierce competition is about to begin... 33 The Korean Animation Explosion Milt Vallas reports on Korea’s growth from humble beginnings to big business. -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

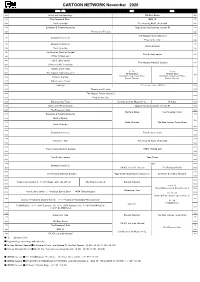

2020 November(2).Xlsx

CARTOON NETWORK November 2020 MON. -FRI. SAT. SUN. 4:00 Grizzy and the Lemmings We Bare Bears 4:00 4:30 The Powerpuff Girls BEN 10 4:30 5:00 Uncle Grandpa The Amazing World of Gumball 5:00 5:30 Sylvester & Tweety Mysteries Oggy & the Cockroaches (season 5) 5:30 6:00 Thomas and Friends 6:00 The Happos Family Season 2 6:30 6:30 Sergeant Keroro(J) Pingu in the City 6:40 7:00 Sergeant Keroro(J) 7:00 Uncle Grandpa 7:30 Uncle Grandpa 7:30 8:00 The Amazing World of Gumball Tom & Jerry series 8:00 8:30 TEEN TiTANS GO! 9:00 Tom & Jerry series The Amazing World of Gumball 9:00 9:30 Grizzy and the Lemmings 10:00 Thomas and Friends 11/7~ 11/1~ 10:30 The Happos Family Season 2 We Bare Bears We Bare Bears 10:00 The New Looney Tunes Show The New Looney Tunes Show 10:40 Pingu in the City Bravest Warriors Bravest Warriors 11:00 Baby Looney Tunes 11:30 Unikitty! 11/15~Eagle Talon NEO(J) 11:30 12:00 Thomas and Friends 12:00 12:30 The Happos Family Season 2 12:30 12:40 Pingu in the City 13:00 Baby Looney Tunes Dorothy and the Wizard of Oz Unikitty! 13:00 13:30 Grizzy and the Lemmings Oggy & the Cockroaches (season 5) 13:30 14:00 The Powerpuff Girls 14:00 We Bare Bears The Powerpuff Girls 14:30 Sylvester & Tweety Mysteries 14:30 15:00 Buck & Buddy 15:00 15:15 Uncle Grandpa The New Looney Tunes Show Uncle Grandpa 15:30 15:30 16:00 16:00 Sergeant Keroro(J) Tom & Jerry series 16:30 16:30 17:00 17:00 Adventure Time The Amazing World of Gumball 17:30 17:30 18:00 18:00 The Amazing World of Gumball TEEN TiTANS GO! 18:30 18:30 19:00 19:00 Tom & Jerry series Teen -

Tribute to Chuck Jones at the Museum of Modern Art. Animator

NO. 25 The Museum of Modern Art FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modemart TRIBUTE TO CHUCK JONES AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART ANIMATOR WILL BE PRESENT CHUCK JONES: THE YEARS AT WARNER BROTHERS, a special four-day program honoring this famous animator and director of such stars as Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Porky Pig, the Roadrunner, and Wile E. Coyote, will take place at The Museum of Modern Art from March 19 through March 22. The program includes a screening of 12 cartoons on Saturday, March 19 at noon, two showings on Sunday, March 20 at noon and 2:30 at which Mr. Jones will be present to discuss his work, and repeat showings of the Sunday programs on Monday, March 21 and Tuesday, March 22 at noon. The film programs, selected by Greg Ford, historian of the American an imated film, are designed to show Chuck Jones' development at Warner Brothers, where he was director of animation for 26 years. Jones began his career in a representational style heavily influences by Disney, but soon developed a more abstract, zanier style of cartooning, shown in "The Dover Boys" of 1942 with its lurched-tempo motion, and "The Aristo-Cat" of 1943 with its expression- istic backgrounds. It was during the fifties, however, while working with Warner's stable of cartoon stars, that Jones fully developed his style, based not on exaggeration but continual refinement. It is a "personality animation," according to Greg Ford, "marked by logical application of space, movement, and editing ideas, and by very subtle drawing that keenly deliniates character attitude." Among the films to be shown during this tribute are "What's Opera Doc," (1957), "Duck Amuck" (1953), "Ali-Baba Bunny" (1957) and "To Beep or Not to Beep" (1964). -

Alex Film Society Presents Cartoon Hall of Fame Big Screen Event

Alex Film Society Presents the Sunday, December 26 2 & 7 pm only Cartoon Hall of Fame Big Screen Event The Rabbit of Seville (1950, Chuck Jones, Warner Bros.) Superman Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd’s long (1941-42, Dave Fleischer, running feud ends up on stage at Paramount) Featuring science the Hollywood Bowl, bringing a fiction plots, stylized environments, new and riotous interpretation to complex cinematography and Rossini’s “Barber of Seville.” human characters in fantastic circumstances, these shorts about the Man of Steel’s battle with mad scientists, arch criminals, wartime enemies and gigantic monsters, began a series that Snow White (1933, Dave Fleischer, Paramount) One of the has had untold influence on both animation and live-action most unusual cartoons ever made is filmmakers to this day.Because 35 mm prints of these a retelling of the Snow White story cartoons are so rare, the title of the short we will see will -years before the Disney feature- be announced during the performance. featuring Betty Boop and a ghostly narrator (Cab Calloway) singing the Duck Dodgers In The 241/2 th “Saint James Infirmary Blues.” Century (1953, Chuck Jones, Warner Bros.) This parody of popular sci-fi serials like “Buck Rogers” and “Flash Gordon”, The Band Concert (1935, Wilfred Jackson, Disney) pits our heroes, Duck Dodgers The first Mickey Mouse cartoon and his “eager young space in color and only the fourth one cadet” Porky, against Marvin the featuring a little scene-stealing Martian (“Commander X-2”) in an escalating and hysterical duck named Donald. The band, intergalactic battle for lludium Phosdex, the shaving cream featuring all of Disney’s early atom. -

Menlo Park Juvi Dvds Check the Online Catalog for Availability

Menlo Park Juvi DVDs Check the online catalog for availability. List run 09/28/12. J DVD A.LI A. Lincoln and me J DVD ABE Abel's island J DVD ADV The adventures of Curious George J DVD ADV The adventures of Raggedy Ann & Andy. J DVD ADV The adventures of Raggedy Ann & Andy. J DVD ADV The adventures of Curious George J DVD ADV The adventures of Ociee Nash J DVD ADV The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin. J DVD ADV The adventures of Pinocchio J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin J DVD ADV v.1 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.1 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.2 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.2 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.3 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.3 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.4 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.4 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.5 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.5 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.6 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.6 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD AGE Agent Cody Banks J DVD AGE Agent Cody Banks J DVD AGE 2 Agent Cody Banks 2 J DVD AIR Air Bud J DVD AIR Air buddies J DVD ALA Aladdin J DVD ALE Alex Rider J DVD ALE Alex Rider J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALICE Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALL All dogs go to heaven J DVD ALL All about fall J DVD ALV Alvin and the chipmunks. -

Living Life Inside the Lines : Tales from the Golden Age of Animation Pdf, Epub, Ebook

LIVING LIFE INSIDE THE LINES : TALES FROM THE GOLDEN AGE OF ANIMATION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Martha Sigall | 245 pages | 15 May 2013 | University Press of Mississippi | 9781578067497 | English | Jackson, United States Living Life inside the Lines : Tales from the Golden Age of Animation PDF Book She states in the book, What I have written is my own recollection of what happened on a day-to-day basis and she tells stories that she feels shouldnt be forgotten of the zany people who make up the animation business. A collection of computer-animated short films. She told me that she got half of what the male animators got, and she was turning out as much footage as they were. Stephen Cavalier. Get Martha Sigall started telling stories from her long career in animation and youll spend hours laughing at the antics of the animators from the golden years of animation. See the link below. Many were life long personal friends. They Drew as They Pleased Vol. To vote on existing books from the list, beside each book there is a link vote for this book clicking it will add that book to your votes. Add to Wishlist. Cinematographic Format: Spherical. Inappropriate The list including its title or description facilitates illegal activity, or contains hate speech or ad hominem attacks on a fellow Goodreads member or author. Be the first! Then this is the book for you Share Full Text for Free beta. Add books from: My Books or a Search. Mel Blanc. Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? Explores the creative process and techniques of Norman McLaren, artist, cinematographer and animator; includes excerpts from McLaren's film vaults, interviews and narration. -

SPACE JAM: a NEW LEGACY” and Other Exciting Stories for Never-Ending Family Fun

“SPACE JAM: A NEW LEGACY” and other exciting stories for never-ending family fun The premiere of “SPACE JAM: A NEW LEGACY” on HBO Max has been the perfect excuse for the entire family to binge watch some of the most fun-filled and hilariously entertaining programs starring their favorite characters available on HBO Max.The new film SPACE JAM: A NEW LEGACY brings together NBA superstar LeBron James and his son Dom, who after being trapped in a digital space created by a rogue AI, must do everything possible in order to get home, while at the same time leading the entire Looney Tunes gang to victory on the basketball court. There, the Tunes face the Goons in the most important challenge of their lives that will redefine LeBron's bond with his son and show him the power of being oneself. Ready for action, the Tunes smash conventions, bring forth their unique talents, and surprise even "King" James by playing the game their way.Along with this story, on HBO Max there are a variety of adventure-filled titles for children and adults to share unforgettable moments. Connect and enjoy the crazy adventures of Bugs Bunny, the most famous animated rabbit in the world with his intelligence, his style and his thousands of jokes; Scooby Doo, a unique dog who accompanies his friends to solve all kinds of mysteries; The Teen Titans, a group of teenagers with superpowers willing to fight against the fiercest villains; and many other stories and characters in:TOM AND JERRYOne of the most beloved rivalries in history continues, when Jerry moves into one of the best hotels in New York City, which will host the wedding of the century in just a few days. -

Monthly Program Synopsis: Disney Women Animators and the History of Cartooning February 26, 2019, MH Library

Monthly Program Synopsis: Disney Women Animators and the History of Cartooning February 26, 2019, MH Library Suman Ganapathy VP Programs, Yvonne Randolph introduced museum educator from the Walt Disney Museum, Danielle Thibodeau, in her signature vivacious style. It was followed by a fascinating and educational presentation by Thibodeau about women animators and their role in the history of cartooning as presented in the Disney Family Museum located in the Presidio, San Francisco. The talk began with a short history of the museum. The museum, which opened in 2009, was created by one of Walt Disney’s daughters, Diane Disney Miller. After discovering shoeboxes full of Walt Disney’s Oscar awards at the Presidio, Miller started a project to create a book about her father, but ended up with the museum instead. Disney’s entire life is presented in the museum’s interactive galleries, including his 248 awards, early drawings, animation, movies, music etc. His life was inspirational. Disney believed that failure helped an individual grow, and Thibodeau said that Disney always recounted examples from his own life where he never let initial failures stop him from reaching his goals. The history of cartooning is mainly the history of Walt Dissey productions. What was achieved in his studios was groundbreaking and new, and it took many hundreds of people to contribute to its success. The Nine Old Men: Walt Disney’s core group of animators were all white males, and worked on the iconic Disney movies, and received more than their share of encomium and accolades. The education team of the Walt Disney museum decided to showcase the many brilliant and under-appreciated women who worked at the Disney studios for the K-12 students instead. -

Tom & Jerry, Bad Influences?

Eindexamen Engels havo 2011 - II havovwo.nl Tekst 1 Tom & Jerry, Bad Influences? 1 Yesterday afternoon I ran across a story about Turner Broadcasting which is currently delving into its catalog of 1,500 hours of Hanna-Barbera cartoons to remove scenes that “glamorize” smoking. The move is in response to one viewer’s complaint about an episode of “Tom and Jerry.” 2 A Turner spokesperson said the viewer had complained about a cartoon in which Tom lights a cigarette in an attempt to 1 a female cat and that only cartoons “where smoking could be deemed to be cool or glamorized,” would be cut and that scenes in which villains smoke will remain untouched. 3 2 , this move will save a generation of youngsters from trying to woo cats with tobacco. Unfortunately, however, those same children are still in danger of dropping anvils on one another’s heads, putting each other’s tails in electrical sockets, cutting each other in half, poisoning one another, exploding each other with dynamite and other sundry weapons available from the diabolical Acme corporation. http://voices.washingtonpost.com, 2006 ▬ www.havovwo.nl - 1 - www.examen-cd.nl ▬ Eindexamen Engels havo 2011 - II havovwo.nl Let op: beantwoord een open vraag altijd in het Nederlands, behalve als het anders is aangegeven. Als je in het Engels antwoordt, levert dat 0 punten op. Tekst 1 Tom & Jerry, bad influences? 1p 1 Which of the following fits the gap in paragraph 2? A hurt B impress C rescue D smoke out 1p 2 Which of the following fits the gap in paragraph 3? A Hopefully B In reality C Ironically D Regrettably 1p 3 How can the tone of paragraph 3 be characterised? A As aggressive. -

Chuck Jones 1 Chuck Jones

Chuck Jones 1 Chuck Jones Chuck Jones Chuck Jones (1978). Nombre real Charles Martin Jones Nacimiento Spokane, Washington, Estados Unidos 21 de septiembre de 1912 Fallecimiento Corona del Mar, California, Estados Unidos 22 de febrero de 2002 (89 años) Familia Cónyuge Dorothy Webster (1935 - 1978) Marian J. Dern (1981 - 2002) Hijo/s Linda Jones Clough Premios Premios Óscar Óscar honorífico 1996 Por su trabajo en los dibujos animados Mejor cortometraje animado 1965 The Dot and the Line [1] Sitio oficial [2] Ficha en IMDb Charles Martin "Chuck" Jones (Spokane (Washington), 21 de septiembre de 1912 – Corona del Mar (California), 22 de febrero de 2002) fue un animador, caricaturista, guionista, productor y director estadounidense, siendo su trabajo más importante los cortometrajes de Looney Tunes y Merrie Melodies del estudio de animación de Warner Brothers. Entre los personajes que ayudó a crear en el estudio se encuentran El Coyote y el Correcaminos, Pepe Le Pew y Marvin el Marciano. Tras su salida de Warner Bros. en 1962, fundó el estudio de animación Sib Tower 12 Productions, con el que produjo cortometrajes para Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, incluyendo una nueva serie de Tom y Jerry y el especial de televisión El Grinch: el Cuento Animado. Jones obtuvo un premio Óscar por su cortometraje The Dot and the Line (1965) y otro honorífico por su labor en la industria cinematográfica.[] Chuck Jones 2 Biografía Primeros años Chuck Jones nació en la ciudad de Spokane (Washington), fue el cuarto hijo de Charles Adam y Mabel Jones. Pocos meses después de su nacimiento se mudó junto a su familia a Los Ángeles (California), específicamente al área de Sunset Boulevard.[] Su hogar estaba ubicado a unas cuadras del estudio de Charles Chaplin, por lo que iba a ver cómo filmaban las películas.[] La pantomima utilizada en las películas mudas fue una importante influencia para su posterior trabajo como animador.[3][] Jones le ha dado el crédito a su padre por su inclinación al arte.