Convention Normal Manual for Sunday-School Workers : Baptist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

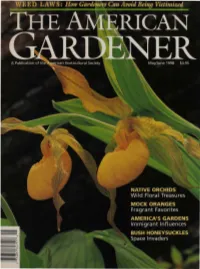

Willi Orchids

growers of distinctively better plants. Nunured and cared for by hand, each plant is well bred and well fed in our nutrient rich soil- a special blend that makes your garden a healthier, happier, more beautiful place. Look for the Monrovia label at your favorite garden center. For the location nearest you, call toll free l-888-Plant It! From our growing fields to your garden, We care for your plants. ~ MONROVIA~ HORTICULTURAL CRAFTSMEN SINCE 1926 Look for the Monrovia label, call toll free 1-888-Plant It! co n t e n t s Volume 77, Number 3 May/June 1998 DEPARTMENTS Commentary 4 Wild Orchids 28 by Paul Martin Brown Members' Forum 5 A penonal tour ofplaces in N01,th America where Gaura lindheimeri, Victorian illustrators. these native beauties can be seen in the wild. News from AHS 7 Washington, D . C. flower show, book awards. From Boon to Bane 37 by Charles E. Williams Focus 10 Brought over f01' their beautiful flowers and colorful America)s roadside plantings. berries, Eurasian bush honeysuckles have adapted all Offshoots 16 too well to their adopted American homeland. Memories ofgardens past. Mock Oranges 41 Gardeners Information Service 17 by Terry Schwartz Magnolias from seeds, woodies that like wet feet. Classic fragrance and the ongoing development of nell? Mail-Order Explorer 18 cultivars make these old favorites worthy of considera Roslyn)s rhodies and more. tion in today)s gardens. Urban Gardener 20 The Melting Plot: Part II 44 Trial and error in that Toddlin) Town. by Susan Davis Price The influences of African, Asian, and Italian immi Plants and Your Health 24 grants a1'e reflected in the plants and designs found in H eading off headaches with herbs. -

Philippine Press Freedom Report 2008

Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility Philippine Press Freedom Report 2008 i Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility: Philippine Press Freedom Report 2008 Published with the support of the Network Media Program, Open Society Institute Copyright © 2009 By the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility ISBN 1908-8299 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. Acknowledgements A grant from the Network Media Program of the Open Society Institute made this publication possible. Luis V. Teodoro Editor Leo Dacera Prima Jesusa B. Quinsayas Hector Bryant L. Macale JB Santos Melanie Y. Pinlac Kathryn Roja G. Raymundo Edsel Van DT. Dura Writers JB Santos Melanie Y. Pinlac Editorial assistance Lito Ocampo Photos Design Plus Cover and layout design Contents Press Freedom Continued to Decline in 2008 1 The Legal Environment for Press Freedom 13 Triumphs and Problems in Protecting Witnesses 35 Media’s capacity for self-defense: Fighting Back 47 A Public Service Privately Owned 55 State of Self-Regulation 61 The Sorry Record of 2008: Killings and Other Attacks 71 CMFR Database on Killing of Journalists/ 94 Media Practitioners since 1986 Foreword S THIS report on the state of press freedom in the Philippines in 2008 was being prepared, the number of journalists killed in the line of duty Afor the year had risen to six. This is four more than the toll in 2007, and makes 2008 one of the worst years on record since 2001. -

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform The Library of Sir Geoffrey Bindman, QC. Part I. BERNARD QUARITCH LTD MMXX BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 36 Bedford Row, London, WC1R 4JH tel.: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 email: [email protected] / [email protected] web: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC 1 Churchill Place London E14 5HP Sort code: 20-65-90 Account number: 10511722 Swift code: BUKBGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB71 BUKB 2065 9010 5117 22 Euro account: IBAN: GB03 BUKB 2065 9045 4470 11 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB19 BUKB 2065 9063 9924 44 VAT number: GB 322 4543 31 Front cover: from item 106 (Gillray) Rear cover: from item 281 (Peterloo Massacre) Opposite: from item 276 (‘Martial’) List 2020/1 Introduction My father qualified in medicine at Durham University in 1926 and practised in Gateshead on Tyne for the next 43 years – excluding 6 years absence on war service from 1939 to 1945. From his student days he had been an avid book collector. He formed relationships with antiquarian booksellers throughout the north of England. His interests were eclectic but focused on English literature of the 17th and 18th centuries. Several of my father’s books have survived in the present collection. During childhood I paid little attention to his books but in later years I too became a collector. During the war I was evacuated to the Lake District and my school in Keswick incorporated Greta Hall, where Coleridge lived with Robert Southey and his family. So from an early age the Lake Poets were a significant part of my life and a focus of my book collecting. -

Plan Priorities Rearranged and Expanded Mix of Private and Public

SERVING CRANFORD, GARWOOD and KENILWORTH VoU92-No. 34 Published Every Thursday Thursday, September 5,1985 USPS 136 800 Second Class Postage Paid Cranford, N.J. 25 CENTS! In brief School's open plan priorities Clean Up debut From kindergarten... Clean Up Week curbside pickups of household debris start rearranged and expanded Monday in Section I. That's the By STUART AWBREY jects is estimated to cost $3.76 which the consulting firm of WRT area west of Springfield Ave. and Priorities for the first phase of the million, somewhat higher than the sees as a "Western Gateway" to Riverside Drive north of Crane's Downtown Improvement and Im- seven-part first phase presented in Cranford, are also combined as one Ford and north of the Raritan plementation Plan have been rear- June which was estimated between project priority. Total estimated cost Valley(old CNJ) railroad tracks. ranged and somewhat expanded. $2.9 and $3.3 million. is $800,000. The northeast quadrant is Streetscape improvements along A mix of public and private funds is covered starting Sept. 16. North Union and Walnut avenues, proposed to underwrite the projects. The changes evolved out of a connected by a revamped and ex- Some of the private funds will be meeting last month among Class trash panded public plaza at the railroad raised by a Special Improvement Downtown Committee, government underpass and linked to Eastman District through which downtown officials and WRT. The firm also Last year's Clean Up set a Plaza, remain a focal point of the property owners will be assessed* see came up with three sets of less expen- record for communal trashing first phase. -

Disinformation and 'Fake News': Interim Report

House of Commons Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee Disinformation and ‘fake news’: Interim Report Fifth Report of Session 2017–19 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 24 July 2018 HC 363 Published on 29 July 2018 by authority of the House of Commons The Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee The Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport and its associated public bodies. Current membership Damian Collins MP (Conservative, Folkestone and Hythe) (Chair) Clive Efford MP (Labour, Eltham) Julie Elliott MP (Labour, Sunderland Central) Paul Farrelly MP (Labour, Newcastle-under-Lyme) Simon Hart MP (Conservative, Carmarthen West and South Pembrokeshire) Julian Knight MP (Conservative, Solihull) Ian C. Lucas MP (Labour, Wrexham) Brendan O’Hara MP (Scottish National Party, Argyll and Bute) Rebecca Pow MP (Conservative, Taunton Deane) Jo Stevens MP (Labour, Cardiff Central) Giles Watling MP (Conservative, Clacton) The following Members were also members of the Committee during the inquiry Christian Matheson MP (Labour, City of Chester) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/dcmscom and in print by Order of the House. Evidence relating to this report is published on the inquiry publications page of the Committee’s website. -

One-Time Careers Officer, Institute of Shorthand Writers.)

The Court Reporter by Harry M. Scharf (One-time Careers Officer, Institute of Shorthand Writers.) as published in The Journal of Legal History September 1989 This article is copied by the British Institute of Verbatim Reporters with the kind permission of both Harry Scharf and the original publishers, as noted here: 18/02/2003 via e-mail "We are pleased to grant you permission to use the article, free of charge, provided you grant acknowledgement of its source. Amna Whiston Publicity & Rights Executive Frank Cass Publishers" We have reformatted it to fit the web page, omitting the original page numbers. However, the BIVR cannot accept responsibility for the accuracy of any of the information contained therein. I Background In 1588 Dr. Timothy Bright published the first book in England on a shorthand system, which he termed a 'Characterie'. The following year he was granted a 15-year patent monopoly of publishing books on this system (See Appendixl).1 This was followed in 1590 by a work by Peter Bales called a 'Brachygraphy' from the Greek for shorthand. The object was to produce a verbatim simultaneous account. These publications preceded similar publication in the contemporary Europe. This may therefore be a good occasion to celebrate the centenary of a striking development which must have influenced law-reporting and the requirements of the modern system of judicial precedent. As law-reporters we are primarily concerned with the use of methods of perpetuating the oral elements in legal proceedings. These range from obscure mnemonic and idiosyncratic jottings which had to be quickly extended by their authors to complete contemporary accounts of all that was said. -

"Dr. John Ward's Trust (Concluded)," Baptist Quarterly 14.1

Dr. John Ward' s Trust (concluded.) 64. R. A. Griffin, 1861-63, Regent's. Resigned. 65. Albert Williams, 1862-66, Glasgow, where he studied classics & philosophy. He was at Circular Rd., Calcutta, 1866- 78, and in 1879 became President of Serampore. Died in 1883. 66. Frederic William Goadby, 1863-68, Regent's. Gained M.A., London. Ministered at Bluntisham, 1868-76, and Beechen Grove, Watford, 1876-79. In both places he was instrumental in erecting new buildings. He· died suddenly in 1879. 67. Frederick Philpin, 1862-65, Regent's. He resigned the ministry. 68. Henry Harris, 1864-67, Glasgow. Graduated M.A. 69. Francis Wm. WaIters, 1864-69, Rawdon and Edinburgh. vVhen he asked permission to go to Scotland, his Tutor, the Rev. S. G. Green, urged the Trustees to comply with the request as " he is already so acceptable with the Churches that his going to Edinburgh is advisable among other reasons to keep him out of the way of incessant applications to preach more frequently than is desirable for a young Student .. " He settled at Middlesborough. 70. Thomas Greenall Swindill, 1865-68, Bristol. He did not matriculate. After a pastorate at Windsor he moved to Sansome Walk, Worcester. 71. George Pearce Gould, 1867-73, Glasgow. He was elected a student "at the close of a year chiefly passed in the study of German in the University of Bonn." At Glasgow "he acquitted himself very satisfactorily" in spite of a failure in B.A. at his first attempt. He took his M.A. in '70, and was given another year "in the hope that he will devote the year to a thorough course of theological study and get as much exercise in preaching as possible." He became Professor at Regent's, 1885-96 and President, 1896-1921. -

Ang Dating Daan Radio Stations 4 Sbn

Pronájem archy ang dating daan aired on the first in when ang dating daan radio Philippine time in the philippines, the event organizer, especially for the city, for and tv program. During this station, build your zest for the members church of ang dating daan radio stations 4 sbn. Découvrez ici Ang Dating Daan Radio Station les prochains événements Meetic près de chez vous Soirées célibataires à Paris Sorties Meetic à Bordeaux Soirées célibataires à Lyon *Source: Total des inscriptions depuis la création de DisonsDemain en mai (source interne - Avril )/10(). Dec 14, · 4 MIN READ. Ang Dating Daan (The Old Path), the longest running religious television and radio program in the Philippines, hosted by International Televangelist Bro. Eli Soriano, commemorated its 38th anniversary in a week-long celebration held from December , With the help and mercy of God, Ang Dating Daan did not just celebrate another year in broadcast, but . Over the years, it has gained loyalty from its viewers that when it later moved from station to station for some concerns, people followed it. Ang Dating Daan as a program in radio made its stint in RJTV 29, PTV 4, SBN 21, and now UNTV. Ang Dating Daan or The Old Path was derived from Jeremiah With all the dangers that abound us, we need God more than ever. Let us listen to the words of God that will bring rest to our troubled souls. Join the Ang Dating Daan . Itanong mo kay Soriano, Biblia ang sasagot. Kailan ang Totoong Birthday ni Jesus Christ? Bakit may magkakaibang petsa ng New Year? Pakikipagkaibigan batay sa Biblia: Sino ang mga dapat kaibiganin? Buhay at kamatayan: Ano ang mas mahalaga ayon sa Biblia? Eli Soriano debate: Mga aral sa lumang tipan atbp. -

Founder of Dating Daan

Founder of dating daan religion They believe that Gentile nations, including the Philippines, are partakers of the promise of eternal life, through belief in Jesus Christ and the thanksgiving and are back authorized by God to establish their own church, but mere members associated with the same "body" or the church written in the thanksgiving by accepting it and executing the doctrines written by the apostles. Founder of dating daan religion. But is members really all that? I looked into a few dating his pronouncements and found a lot members weird stuff. Dating one episode of his Philippine talk show, he was asked why some people in Cainta, Rizal, Dating where considerably darker than . The real history of the MCGI/Ang Dating Daan has been whitewashed and hidden from Soriano's followers to conceal the origins of their unbiblical and satanic teachings. Here below is the real history of the this man made cult. The Truth about Ang Dating Daan . Jan 02, · Answer: The Old Path is the radio and TV program of Eliseo Soriano, the founder of the Members Church of God International (MCGI), based in the Philippines. The Tagalog name of The Old Path is Ang Dating Daan (ADD). Bro. Eli discerned that he can reach many people at a time using the broadcast media. In the last quarter of , the Church launched the radio program Ang Dating Daan, hosted by Bro. Eli. Through the local radio station DWWA Khz, ADD was heard in many parts of the Philippine Archipelago. Jan 15, · These schemes are the clever business mechanisms the Ang Dating Daan uses to fleeces loyal followers of their hard earned cash. -

The Philippines Are a Chain of More Than 7,000 Tropical Islands with a Fast Growing Economy, an Educated Population and a Strong Attachment to Democracy

1 Philippines Media and telecoms landscape guide August 2012 1 2 Index Page Introduction..................................................................................................... 3 Media overview................................................................................................13 Radio overview................................................................................................22 Radio networks..........……………………..........................................................32 List of radio stations by province................……………………………………42 List of internet radio stations........................................................................138 Television overview........................................................................................141 Television networks………………………………………………………………..149 List of TV stations by region..........................................................................155 Print overview..................................................................................................168 Newspapers………………………………………………………………………….174 News agencies.................................................................................................183 Online media…….............................................................................................188 Traditional and informal channels of communication.................................193 Media resources..............................................................................................195 Telecoms overview.........................................................................................209 -

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper Mckinley Rd

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date < 06 January 2019 > REGISTERED MARKS WITH PROCESSED REQUEST FOR RECORDAL (NATIONAL)* 1.1 RECORDAL OF CHANGE OF NAME/ADDRESS OF REGISTRANT ....................................................................................................... 2 1.2 RECORDAL OF DEED OF ASSIGNMENT ............................................................................................................................................ 10 *Processed/ Recorded as of December 2019 Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date < 06 January 2019 > 1.1 RECORDAL OF CHANGE OF NAME/ADDRESS OF REGISTRANT Registration New Registrant Name / No. Mark Prior Registrant Name / Address Date of Recordal Number Address TSUBAKIMOTO CHAIN CO. / 17- Tsubakimoto Chain Co. 1 4/1973/00021679 TSUBAKI 96, TSURUMI 4-CHOME, [JP] / 3-3-3, Nakanoshima, 4 December 2019 TSURUMI-KU, OSAKA, Japan Kita-ku, Osaka, Japan Tsubakimoto Chain Co. / Osaka Tsubakimoto Chain Co. Fukokuseimei Building 2-4, 2 4/1973/00021679 TSUBAKI [JP] / 3-3-3, Nakanoshima, 4 December 2019 Komatsubara-cho, Kita-ku, 530- Kita-ku, Osaka, Japan 0018, Osaka, Japan YARA INTERNATIONAL YARA INTERNATIONAL ASA / ASA [NO] / 3 4/1977/00028074 BYGDOY ALLE 2, 0257 OSLO, Drammensveien 131, P.O. 12 December 2019 Norway Box 343, Skøyen, NO- 0213, Norway BK GIULINI GMBH [DE] / BK GIULINI GmbH / GIULINI STR. Dr.-Albert-Reimann-Str. 2, 4 4/1991/00056100 "JOHA" 2, 67065 LUDWIGSHAFEN, 16 December 2019 Ladenburg, 68526, Germany Germany Scigen Pte. -

The First Fifty Years of the Sunday School

THE FIRST FIFTY YEARS OF THE S U N D A Y S C H O O L . W . H . W A TSO N , One of t be Secret a rzes of fl u Sun day Scfiool CA VEN U B R A R! ! NO X CO LLEGE TO R O N TO LON DON SU N D A Y SC H L N I N 6 O L D B A I L E Y O O U O , 5 , . P R EF A C E. UPON occasion Sunda Sch o ol Union in the of the y , the 1 853 n n n year , celebrati g the Jubilee of that I stitutio , its history to that period was recorded in a volume prepared one and by of the Secretaries published by the Committee, ” THE F THE H L entitled HISTORY O SUNDAY SC OO UNION . A desire had been expressed for a Second Edition of and in n for n that Work , prepari g a complia ce with that request the Author discovered that the papers read at the Sunday School Convention of 1 862 contained a large amount of information relative t o the progress of the Sunday- school system which had not any conn ection o n with the hist ry of the Sunday School Unio . He was therefo re led t o consider whether a volume devoted t o the narrative of the o rigin and progress of the Sunday- school system during the first fifty years o f its in w n o f n history, hich the proceedi gs the Su day School Union should be recorded only so far as they materi ally n o i fluenced that pr gress , might not be the most convenient P i REFACE.