The Marketing of NASCAR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Busch's Battle Ends in Glory

8 – THE DERRICK. / The News-Herald Wednesday, December 09, 2015 QUESTIONS & ATTITUDE Compelling questions... and maybe a few actual answers What will I do for NASCAR news? It’s as close as we get to NASCAR hanging a “Gone fishing” sign on the door. Now what? After 36 races, a goodbye to Jeff Gordon and con- SPEED FREAKS gratulations to Kyle Busch, and with only about A couple questions Mission accomplished two months until the engines crank at Daytona, we had to ask — you need more right now? These days, this is the ourselves closest thing NASCAR has to a dark season. But there’ll be news. What sort of news? Danica Patrick’s NASCAR’s corner-office suits are huddling with newest Busch’s battle the boys in legal to find a feasible way to turn its race teams into something resembling fran- GODSPEAK: Third chises, which would break from the independent- crew chief in contractor system that served the purposes four years. Crew since the late-’40s. Well, it served NASCAR’s ends in glory purposes, along with owners and drivers who chief No. 1, Tony Gibson, took ran fast enough to escape creditors. But times Kurt Busch to the have changed; you’ll soon be reading a lot about men named Rob Kauffman and Brent Dewar and Chase this year. something called the Race Team Alliance. KEN’S CALL: It’s starting to take on Will it affect the race fans and the the feel of a dial- racing? a-date, isn’t it? Nope. So maybe you shouldn’t pay attention. -

KEVIN HARVICK: Track Performance History

KEVIN HARVICK: Track Performance History ATLANTA MOTOR SPEEDWAY (1.54-mile oval) Year Event Start Finish Status/Laps Laps Led Earnings 2019 Folds of Honor 500 18 4 Running, 325/325 45 N/A 2018 Folds of Honor 500 3 1 Running, 325/325 181 N/A 2017 Folds of Honor 500 1 9 Running, 325/325 292 N/A 2016 Folds of Honor 500 6 6 Running, 330/330 131 N/A 2015 Folds of Honor 500 2 2 Running, 325/325 116 $284,080 2014 Oral-B USA 500 1 19 Running, 325/325 195 $158,218 2013 AdvoCare 500 30 9 Running, 325/325 0 $162,126 2012 ×AdvoCare 500 24 5 Running, 327/327 101 $172,101 2011 AdvoCare 500 21 7 Running, 325/325 0 $159,361 2010 ×Kobalt Tools 500 35 9 Running, 341/341 0 $127,776 Emory Healthcare 500 29 33 Vibration, 309/325 0 $121,026 2009 ×Kobalt Tools 500 10 4 Running, 330/330 0 $143,728 Pep Boys Auto 500 18 2 Running, 325/325 66 $248,328 2008 Kobalt Tools 500 8 7 Running, 325/325 0 $124,086 Pep Boys Auto 500 6 13 Running, 325/325 0 $144,461 2007 Atlanta 500 36 25 Running, 324/325 1 $117,736 ×Pep Boys Auto 500 34 15 Running, 329/329 1 $140,961 2006 Golden Corral 500 6 39 Running, 313/325 0 $102,876 †Bass Pro Shops 500 2 31 Running, 321/325 9 $123,536 2005 Golden Corral 500 36 21 Running, 324/325 0 $106,826 Bass Pro Shops/MBNA 500 31 22 Running, 323/325 0 $129,186 2004 Golden Corral 500 8 32 Running, 318/325 0 $90,963 Bass Pro Shops/MBNA 500 9 35 Engine, 296/325 0 $101,478 2003 Bass Pro Shops/MBNA 500 I 17 19 Running, 323/325 0 $87,968 Bass Pro Shops/MBNA 500 II 10 20 Running, 324/325 41 $110,753 2002 MBNA America 500 8 39 Running, 254/325 0 $85,218 -

NASCAR-Daytona 500 Advertising Advisory

NASCAR/Daytona 500 Advertising Advisory The Daytona 500 is held every February at the Daytona International Speedway in Daytona, Florida. Many advertisers, especially bars and restaurants, will want to advertise Daytona 500 related promotions in the days and weeks leading up to the race. Even though the advertising blitz maybe heavy, it’s important to remember the law regarding the use of NASCAR/Daytona 500 trademarks. NASCAR and the Daytona 500 International Speedway control all marketing and proprietary rights with respect to the race. Both NASCAR and the Daytona 500 use their trademarks in order to generate revenue and both reserve the use of trademarked material to official sponsors and licensees who have invested large amounts of money to acquire the specific rights to these marks. NASCAR and the Daytona 500 International Speedway retain the exclusive right to control marketing of the race and all of its associated trademarks. These trademarks include the phrases “Daytona 500,” “The Great American Race, and the name of the racetrack itself, “The Daytona 500 International Speedway,” as well as all other associated graphics and logos. Additionally, the term “NASCAR” is a registered trademark of the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing, Inc. Just as in other sports, individual racing teams also own federally registered trademarks for their team names and drivers (e.g., “Jack Roush Racing” or “Dale Earnhardt, Inc.”), nicknames, uniform, helmet and car designs. Without the express permission of NASCAR and/or the Daytona 500 -

Daytona 500 Coverage Live on Siriusxm

NEWS RELEASE Daytona 500 Coverage Live on SiriusXM 2/12/2018 Fans nationwide get live broadcast of 60th Daytona 500 on Feb. 18 Extensive coverage from the track on race day and throughout Speedweeks on SiriusXM NASCAR Radio Kevin Harvick hosts his show, "Happy Hours," live from Daytona on Feb. 14 NEW YORK, Feb. 12, 2018 /PRNewswire/ -- SiriusXM will offer the most comprehensive audio coverage of the 60th running of the Daytona 500 on February 18, as well as all the news and events of NASCAR's anticipated Speedweeks leading up to race day. Subscribers nationwide will have access to the live race broadcast, in-car audio from some of the sport's top drivers, and daily coverage from Daytona International Speedway. On Daytona 500 race day, SiriusXM will offer 15 hours of live programming from the speedway starting at 7:00 am ET. Subscribers will hear every turn of the "The Great American Race" (green flag approximately 2:30 pm ET) plus full pre- and post-race coverage with expert analysis, reports from pit road and the garages, driver introductions and interviews with the race winner and other drivers. The programming airs on the exclusive 24/7 SiriusXM NASCAR Radio channel (ch. 90). Go to www.SiriusXM.com/NASCAR for more info. SiriusXM NASCAR Radio will also provide live coverage of the Can-Am Duel, the 150-mile Monster Energy NASCAR Cup Series qualifying races, on Thursday, Feb. 15 (6:00 pm ET), the NextEra Energy Resources 250 NASCAR Camping World Truck Series race on Friday, Feb. 16 (7:00 pm ET), and the Power Shares QQQ 300 NASCAR Xfinity Series race on Saturday, Feb. -

0623 Gdp Sun D

ExportPDFPages_ExportPDFPages6/21/20138:32PMPageD1 WWW.GWINNETTDAILYPOST.COM SUNDAY, JUNE 23, 2013 D1 STAFFING PUBLIC SALES/ PUBLIC SALES/ FULL TIME DIRECTORY AUCTIONS AU CTIONS PUBLIC SALE SUWANEE, GA 30024 MEDICAL Notice is hereby given (678) 513-8185 7/09/2013 Longleaf Hospice that pursuant to the State’s 9:45 AM is Hiring! Self-Storage Facility Act on STORED BY THE FOLLOW- July 09, 2013 at 11:30 AM ING PERSONS: * PRN RN Case at Site #0697, 3313 Stone A1079 Marcus Smith Managers Mountain Hwy., Snellville, B2206 Lyvelle Simms * Admissions Georgia, the undersigned, B2236 crystal sparks Nurses CubeSmart Store General 1st, 2nd, & Manager will sell at public PUBLIC STORAGE PROP- * Social Workers Weekend avail. sale the following stored * Home Health ERTY : 25595 Light Industrial property: 66 OLD PEAC HTREE RD. Aides Assemble Displays Name; Unit #; General De- SUWANEE, GA 30024 * LPNs & Picker/Packer scription of Property (770) 338-1271 7/09/2013 Chaplains $8-$8.70 + incentive 10:00 AM Strong preference Apply online today at: WILLIAM T OWENS STORED BY THE FOLLOW- given to candidates www.unitedstaffing C32 ING PERSONS: with 1+ years Hos- service.com MISC household goods, 00117 MICHAEL GOKEY BOXES, AND PERSONAL 00425 TRACEY BLANTON pice experience. EOE ITEMS Minimum of 12 4084 Jonathan Upshur months licensed - JERRY McCOLUMN PUBLIC STORAGE PROP- professional experi- C143 ERTY: 28158 Plans fforor the FFall?aall? ATLANTTAA VOCAATITIONAL ence required, pref- Misc household goods, Fur- 495 BUFORD DR. MMakake a date with us fforor your neeww ccarreeeer! erably in Hospice. niture, GRILL, Boxes, AND LAWRENCEVILLE, GA 30245 SCHOOL Send resume to: PERSONAL ITEMS (770) 338-1271 7/09/2013 careers@longleaf PUBLIC HEARINGS 10:15AM hospice.com STACY M WEEMS MEDICAL ASSISTTANTANT C.N.A. -

Fedex Racing Press Materials 2013 Corporate Overview

FedEx Racing Press Materials 2013 Corporate Overview FedEx Corp. (NYSE: FDX) provides customers and businesses worldwide with a broad portfolio of transportation, e-commerce and business services. With annual revenues of $43 billion, the company offers integrated business applications through operating companies competing collectively and managed collaboratively, under the respected FedEx brand. Consistently ranked among the world’s most admired and trusted employers, FedEx inspires its more than 300,000 team members to remain “absolutely, positively” focused on safety, the highest ethical and professional standards and the needs of their customers and communities. For more information, go to news.fedex.com 2 Table of Contents FedEx Racing Commitment to Community ..................................................... 4-5 Denny Hamlin - Driver, #11 FedEx Toyota Camry Biography ....................................................................... 6-8 Career Highlights ............................................................... 10-12 2012 Season Highlights ............................................................. 13 2012 Season Results ............................................................... 14 2011 Season Highlights ............................................................. 15 2011 Season Results ............................................................... 16 2010 Season Highlights. 17 2010 Season Results ............................................................... 18 2009 Season Highlights ........................................................... -

Numerical Kansas Speedway Banquet 400 Provided by NASCAR Statistical Services - Fri, Sep 29, 2006 @ 11:13 AM Eastern

Entry List - Numerical Kansas Speedway Banquet 400 Provided by NASCAR Statistical Services - Fri, Sep 29, 2006 @ 11:13 AM Eastern Car Driver Driver's Hometown Team Name Owner 1 01 Joe Nemechek Lakeland, FL U.S. Army Chevrolet Robert Ginn 2 1 Martin Truex Jr. # Mayetta, NJ Bass Pro Shops/Tracker Chevrolet Teresa Earnhardt 3 2 Kurt Busch Las Vegas, NV Miller Lite Dodge Roger Penske 4 * 4 Scott Wimmer Wausau, WI Lucas Oil Chevrolet Larry McClure 5 5 Kyle Busch Las Vegas, NV Kellogg's Chevrolet Rick Hendrick 6 * 06 Todd Kluever Sun Prairie, WI 3M Ford Jack Roush 7 6 Mark Martin Batesville, AR AAA Ford Jack Roush 8 07 Clint Bowyer # Emporia, KS Jack Daniel's Chevrolet Richard Childress 9 7 Robby Gordon Orange, CA Harrah's Chevrolet Robby Gordon 10 8 Dale Earnhardt Jr. Kannapolis, NC Budweiser Chevrolet Teresa Earnhardt 11 9 Kasey Kahne Enumclaw, WA Dodge Dealers/UAW Dodge Ray Evernham 12 10 Scott Riggs Bahama, NC Valvoline/Stanley Tools Dodge James Rocco 13 11 Denny Hamlin # Chesterfield, VA FedEx Freight Chevrolet J.D. Gibbs 14 12 Ryan Newman South Bend, IN Alltel Dodge Roger Penske 15 14 Sterling Marlin Columbia, TN Ginn Clubs & Resorts Chevrolet Robert Ginn 16 16 Greg Biffle Vancouver, WA National Guard/Subway Ford Geoffrey Smith 17 17 Matt Kenseth Cambridge, WI DeWalt Ford Mark Martin 18 18 J.J. Yeley # Phoenix, AZ Interstate Batteries Chevrolet Joe Gibbs 19 19 Elliott Sadler Emporia, VA Dodge Dealers/UAW Dodge Ray Evernham 20 20 Tony Stewart Rushville, IN The Home Depot Chevrolet Joe Gibbs 21 21 Ken Schrader Fenton, MO Motorcraft/USAF -

Cannes Critics Week Panel Films Screened During TIFF Cinematheque's Fifty Years of Discovery: Cannes Critics Week (Jan. 18-22

Cannes Critics Week panel Films screened during TIFF Cinematheque’s Fifty Years of Discovery: Cannes Critics Week (Jan. 18-22, 2012) In honour of the fiftieth anniversary of Semaine de la Critique (Cannes Critics Week), TIFF Cinematheque invited eight local and international critics and opinion-makers to each select and introduce a film that was discovered at the festival. The diversity of their selections—everything from revered art-house classics to scrappy American indies, cutting-edge cult hits and intriguingly unknown efforts by famous names—testifies to the festival’s remarkable breadth and eclecticism, and its key role in discovering new generations of filmmaking talent. Programmed by Brad Deane, Manager of Film Programmes. Clerks. Dir. Kevin Smith, 1994, U.S. 92 mins. Production Co.: View Askew Productions / Miramax Films. Introduced by George Stroumboulopoulos, host of CBC’s Stroumboulopoulos Tonight, formerly known as The Hour. Stroumboulopoulos on Clerks: “When Kevin Smith made Clerks and it got on the big screen, you felt like our voice was winning.” Living Together (Vive ensemble). Dir. Anna Karina, 1973, France. 92 mins. Production Co.: Raska Productions / Société Nouvelle de Cinématographie (SNC). Introduced by author and former critic for the Chicago Reader, Jonthan Rosenblum. Rosenblum on Living Together: “I saw Living Together when it was first screened at Cannes in 1973, and will never forget the brutality with which this gently first feature was received. One prominent English critic, the late Alexander Walker, asked Anna Karina after the screening whether she realized that her first film was only being shown because she was once married to a famous film director; she sweetly asked in return whether she should have therefore rejected the Critics Week’s invitation. -

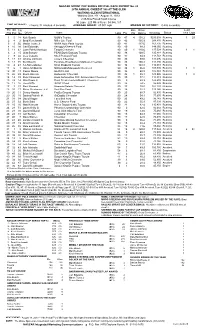

Lead Fin Pos Driver Team Laps Pts Bns Pts Winnings Status Tms Laps

NASCAR SPRINT CUP SERIES OFFICIAL RACE REPORT No. 22 28TH ANNUAL CHEEZ-IT 355 AT THE GLEN WATKINS GLEN INTERNATIONAL Watkins Glen, NY - August 11, 2013 2.45-Mile Paved Road Course 90 Laps - 220 Miles Purse: $4,946,167 TIME OF RACE: 2 hours, 32 minutes, 4 seconds AVERAGE SPEED: 87.001 mph MARGIN OF VICTORY: 0.486 second(s) Fin Str Car Bns Driver Lead Pos Pos No Driver Team Laps Pts Pts Rating Winnings Status Tms Laps 1 5 18 Kyle Busch M&M's Toyota 90 47 4 138.2 $236,658 Running 1 29 2 8 2 Brad Keselowski Miller Lite Ford 90 42 105.9 204,876 Running 3 3 56 Martin Truex Jr NAPA Auto Parts Toyota 90 41 117.6 161,735 Running 4 16 99 Carl Edwards Kellogg's/Cheez-It Ford 90 40 99.2 149,360 Running 5 11 42 Juan Pablo Montoya Target Chevrolet 90 40 1 110.6 137,524 Running 1 1 6 2 15 Clint Bowyer PEAK/Duck Dynasty Toyota 90 38 109.5 135,818 Running 7 9 22 Joey Logano Shell Pennzoil Ford 90 37 94.8 118,743 Running 8 18 48 Jimmie Johnson Lowe's Chevrolet 90 36 89.6 131,296 Running 9 13 78 Kurt Busch Furniture Row/Denver Mattress Chevrolet 90 35 100.3 111,330 Running 10 4 47 AJ Allmendinger Scott Products Toyota 90 34 103.8 116,018 Running 11 6 1 Jamie McMurray McDonald's/Monopoly Chevrolet 90 34 1 96.0 109,505 Running 1 1 12 30 13 Casey Mears GEICO Ford 90 32 68.5 105,843 Running 13 26 29 Kevin Harvick Budweiser Chevrolet 90 32 1 85.1 123,946 Running 1 8 14 14 39 Ryan Newman Haas Automation 30th Anniversary Chevrolet 90 30 77.2 113,318 Running 15 29 14 Max Papis (i) Rush Truck Centers/Mobil 1 Chevrolet 90 0 68.9 122,210 Running 16 17 16 Greg Biffle 3M/811 Ford 90 28 74.5 92,085 Running 17 7 27 Paul Menard Menards/Splash Chevrolet 90 27 79.6 107,201 Running 18 33 17 Ricky Stenhouse Jr # Best Buy Ford 90 26 52.3 123,146 Running 19 20 11 Denny Hamlin FedEx Ground Toyota 90 25 68.7 92,835 Running 20 35 10 Danica Patrick # GoDaddy Chevrolet 90 24 54.1 77,635 Running 21 31 34 David Ragan Taco Bell Ford 90 23 49.2 98,243 Running 22 27 32 Boris Said U.S. -

NASCAR for Dummies (ISBN

spine=.672” Sports/Motor Sports ™ Making Everything Easier! 3rd Edition Now updated! Your authoritative guide to NASCAR — 3rd Edition on and off the track Open the book and find: ® Want to have the supreme NASCAR experience? Whether • Top driver Mark Martin’s personal NASCAR you’re new to this exciting sport or a longtime fan, this insights into the sport insider’s guide covers everything you want to know in • The lowdown on each NASCAR detail — from the anatomy of a stock car to the strategies track used by top drivers in the NASCAR Sprint Cup Series. • Why drivers are true athletes NASCAR • What’s new with NASCAR? — get the latest on the new racing rules, teams, drivers, car designs, and safety requirements • Explanations of NASCAR lingo • A crash course in stock-car racing — meet the teams and • How to win a race (it’s more than sponsors, understand the different NASCAR series, and find out just driving fast!) how drivers get started in the racing business • What happens during a pit stop • Take a test drive — explore a stock car inside and out, learn the • How to fit in with a NASCAR crowd rules of the track, and work with the race team • Understand the driver’s world — get inside a driver’s head and • Ten can’t-miss races of the year ® see what happens before, during, and after a race • NASCAR statistics, race car • Keep track of NASCAR events — from the stands or the comfort numbers, and milestones of home, follow the sport and get the most out of each race Go to dummies.com® for more! Learn to: • Identify the teams, drivers, and cars • Follow all the latest rules and regulations • Understand the top driver skills and racing strategies • Have the ultimate fan experience, at home or at the track Mark Martin burst onto the NASCAR scene in 1981 $21.99 US / $25.99 CN / £14.99 UK after earning four American Speed Association championships, and has been winning races and ISBN 978-0-470-43068-2 setting records ever since. -

INNOVATIONS 8-08.Qxd

INNOVATIONS ISSUE 8, SUMMER 2008 ENGINEEREDENGINEERED ATOMIZATION: ATOMIZATION: PATENTEDPATENTED “LV“LV TECHNOLOGY”TECHNOLOGY” DENNISDENNIS MATHEWSON: MATHEWSON: “FOOLING“FOOLING A A TERMITE” TERMITE” CLASSICCLASSIC COLLISION COLLISION REPAIR REPAIR CENTER: CENTER: TURNINGTURNING PAINT PAINT INTO INTO PROFIT PROFIT NEWNEW MANIFOLD MANIFOLD AUTOMATIC AUTOMATIC SPRAYSPRAY GUNS GUNS WOODWOOD BROTHERS BROTHERS RACING RACING #21#21 INNOVATIONS IN THIS ISSUE ANEST IWATA USA, Inc. 9920 Windisch Road In this eighth installment of INNOVATIONS, we will relay a message from ANEST West Chester, OH 45069 Tel: 513.755.3100 IWATA Corporation’s President, Mr. Takahiro Tsubota. We will also present: Fax: 513.755.0888 www.anestiwata.com • “Turning paint into profit” through waterborne conversion. • Engineered atomization, our patented LV Technology. INNOVATIONS is published quarterly by • Dennis Mathewson “fooling a termite” with his woodgrain airbrushing technique. ANEST IWATA USA, Inc. • New manifold automatic spray guns from ANEST IWATA. While ANEST IWATA USA, Inc. • More creativity from Iwata-Medea and Artool. attempts to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this • Wood Brothers Racing #21. publication, articles are accepted and published upon the representation by contributing writers that they are authorized to submit the entire contents and subject matter thereof and that such publication will not violate any law or infringe upon any right of any party. No part of INNOVATIONS may be reproduced in any form without the express permission -

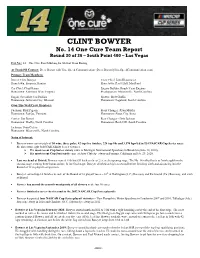

CLINT BOWYER No

CLINT BOWYER No. 14 One Cure Team Report Round 30 of 36 – South Point 400 – Las Vegas Car No.: 14 – One Cure Ford Mustang for Stewart-Haas Racing At Track PR Contact: Drew Brown with True Speed Communication ([email protected]) Primary Team Members: Driver: Clint Bowyer Crew Chief: John Klausmeier Hometown: Emporia, Kansas Hometown: Perry Hall, Maryland Car Chief: Chad Haney Engine Builder: Roush Yates Engines Hometown: Fairmont, West Virginia Headquarters: Mooresville, North Carolina Engine Specialist: Jon Phillips Spotter: Brett Griffin Hometown: Jefferson City, Missouri Hometown: Pageland, South Carolina Over-The-Wall Crew Members: Fuelman: Rick Pigeon Front Changer: Ryan Mulder Hometown: Fairfax, Vermont Hometown: Sioux City, Iowa Carrier: Jon Bernal Rear Changer: Chris Jackson Hometown: Shelby, North Carolina Hometown: Rock Hill, South Carolina Jackman: Sean Cotten Hometown: Mooresville, North Carolina Notes of Interest: • Bowyer owns career totals of 10 wins, three poles, 82 top-five finishes, 224 top-10s and 3,170 laps led in 534 NASCAR Cup Series races. He also owns eight NASCAR Xfinity Series victories. His most recent Cup Series victory came at Michigan International Speedway in Brooklyn (June 10, 2018). His most recent Cup Series pole came at Auto Club Speedway in Fontana, California on Feb. 29, 2020. Last weekend at Bristol: Bowyer started 11th but fell back as far as 21st in the opening stage. The No. 14 rallied back to finish eighth in the second stage, earning three bonus points. In the final stage, Bowyer climbed as high as second before finishing sixth and advancing into the Round of 12 in playoff competition.