Downsizing Democracy Crenson, Matthew A., Ginsberg, Benjamin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011 Annual Report Dear Friends

2011 ANNUAL REPORT DEar FRIENDS: When engaged in the mission of the Vietnam Veterans The Call for Photos is a Memorial Fund, there is a word that I’m particularly fond of. primary focus at each of The That word is: momentum. For those connected with VVMF, Wall that Heals tour stops. 2011 was all about building momentum. In the course of VVMF’s 2011 tour season hit OUR MISSION this one year, the programs we dedicated ourselves to have over 30 cities, maximizing gathered more and more steam, and resulted in forward awareness and fundraising for To preserve the legacy of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, motion that is carrying us closer to the goals contained in our the Education Center. mission statement. to promote healing and to educate about the impact of In 2011, we produced and It is this momentum that will take us into our 30th released a new Build the Center Warren Kahle the Vietnam War Anniversary year, and far beyond. The energy and drive public service announcement 2011 ANNUAL REPORT created in 2011 will propel us as we go about the challenge campaign. The beautifully filmed PSAs included notable of making the dream of the Education Center at The Wall a Americans sending the powerful message of, “Get involved reality. In it, we will honor those who fell in Vietnam, those and help them build it.” who fought and returned, as well as the friends and families of all who served. To highlight the grassroots activities and fundraising efforts, we dramatically increased and improved VVMF’s online Since 1982, The Wall has stood as a solemn tribute to those presence. -

Dahl and Charles E

PLEASE READ BEFORE PRINTING! PRINTING AND VIEWING ELECTRONIC RESERVES Printing tips: ▪ To reduce printing errors, check the “Print as Image” box, under the “Advanced” printing options. ▪ To print, select the “printer” button on the Acrobat Reader toolbar. DO NOT print using “File>Print…” in the browser menu. ▪ If an article has multiple parts, print out only one part at a time. ▪ If you experience difficulty printing, come to the Reserve desk at the Main or Science Library. Please provide the location, the course and document being accessed, the time, and a description of the problem or error message. ▪ For patrons off campus, please email or call with the information above: Main Library: [email protected] or 706-542-3256 Science Library: [email protected] or 706-542-4535 Viewing tips: ▪ The image may take a moment to load. Please scroll down or use the page down arrow keys to begin viewing this document. ▪ Use the “zoom” function to increase the size and legibility of the document on the screen. The “zoom” function is accessed by selecting the “magnifying glass” button on the Acrobat Reader toolbar. NOTICE CONCERNING COPYRIGHT The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproduction of copyrighted material. Section 107, the “Fair Use” clause of this law, states that under certain conditions one may reproduce copyrighted material for criticism, comment, teaching and classroom use, scholarship, or research without violating the copyright of this material. Such use must be non-commercial in nature and must not impact the market for or value of the copyrighted work. -

A WAY FORWARD with IRAN? Options for Crafting a U.S. Strategy

A WAY FORWARD WITH IRAN? Options for Crafting a U.S. Strategy THE SOUFAN CENTER FEBRUARY 2021 A WAY FORWARD WITH IRAN? OPTIONS FOR CRAFTING A U.S. STRATEGY A WAY FORWARD WITH IRAN? Options for Crafting a U.S. Strategy THE SOUFAN CENTER FEBRUARY 2021 Cover photo: Associated Press Photo/Photographer: Mohammad Berno 2 A WAY FORWARD WITH IRAN? OPTIONS FOR CRAFTING A U.S. STRATEGY CONTENTS List of Abbreviations 4 List of Figures 5 Key Findings 6 How Did We Reach This Point? 7 Roots of the U.S.-Iran Relationship 9 The Results of the Maximum Pressure Policy 13 Any Change in Iranian Behavior? 21 Biden Administration Policy and Implementation Options 31 Conclusion 48 Contributors 49 About The Soufan Center 51 3 A WAY FORWARD WITH IRAN? OPTIONS FOR CRAFTING A U.S. STRATEGY LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS BPD Barrels Per Day FTO Foreign Terrorist Organization GCC Gulf Cooperation Council IAEA International Atomic Energy Agency ICBM Intercontinental Ballistic Missile IMF International Monetary Fund IMSC International Maritime Security Construct INARA Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act INSTEX Instrument for Supporting Trade Exchanges IRGC Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps IRGC-QF Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps - Qods Force JCPOA Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action MBD Million Barrels Per Day PMF Popular Mobilization Forces SRE Significant Reduction Exception 4 A WAY FORWARD WITH IRAN? OPTIONS FOR CRAFTING A U.S. STRATEGY LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Iran Annual GDP Growth and Change in Crude Oil Exports 18 Figure 2: Economic Effects of Maximum Pressure 19 Figure 3: Armed Factions Supported by Iran 25 Figure 4: Comparison of Iran Nuclear Program with JCPOA Limitations 28 5 A WAY FORWARD WITH IRAN? OPTIONS FOR CRAFTING A U.S. -

The National Security Council and the Iran-Contra Affair

THE NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL AND THE IRAN- CONTRA AFFAIR Congressman Ed Jenkins* and Robert H. Brink** I. INTRODUCTION Early in November of 1986, newspapers in the United States carried the first reports that the United States government, in an effort to gain release of United States citizens held hostage by terrorists in Lebanon, had engaged in a covert policy of supplying arms to elements within Iran.' Later in that month, following a preliminary inquiry into the matter, it was revealed that some of the funds generated from those arms sales had been diverted to support the "Contra" 2 forces fighting the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. The events giving rise to these disclosures became known collectively as the "Iran-Contra Affair." Both elements of the affair raised serious questions regarding the formulation and conduct of our nation's foreign policy. In regard to the Iranian phase of the affair, the Regan administration's rhetoric had placed the administration firmly in op- position to any dealings with nations supporting terrorism, and with Iran in particular.' In addition, the United States had made significant * Member, United States House of Representatives, Ninth District of Georgia. LL.B., University of Georgia Law School, 1959. In 1987, Congressman Jenkins served as a member of the House Select Committee to Investigate Covert Arms Transactions with Iran. ** Professional Staff Member, Committee on Government Operations, United States House of Representatives. J.D., Marshall-Wythe School of Law, College of William and Mary, 1978. In 1987, Mr. Brink served as a member of the associate staff of the House Select Committee to Investigate Covert Arms Transactions with Iran. -

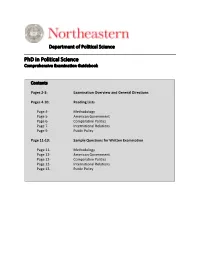

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

Arend Lijphart and the 'New Institutionalism'

CSD Center for the Study of Democracy An Organized Research Unit University of California, Irvine www.democ.uci.edu March and Olsen (1984: 734) characterize a new institutionalist approach to politics that "emphasizes relative autonomy of political institutions, possibilities for inefficiency in history, and the importance of symbolic action to an understanding of politics." Among the other points they assert to be characteristic of this "new institutionalism" are the recognition that processes may be as important as outcomes (or even more important), and the recognition that preferences are not fixed and exogenous but may change as a function of political learning in a given institutional and historical context. However, in my view, there are three key problems with the March and Olsen synthesis. First, in looking for a common ground of belief among those who use the label "new institutionalism" for their work, March and Olsen are seeking to impose a unity of perspective on a set of figures who actually have little in common. March and Olsen (1984) lump together apples, oranges, and artichokes: neo-Marxists, symbolic interactionists, and learning theorists, all under their new institutionalist umbrella. They recognize that the ideas they ascribe to the new institutionalists are "not all mutually consistent. Indeed some of them seem mutually inconsistent" (March and Olsen, 1984: 738), but they slough over this paradox for the sake of typological neatness. Second, March and Olsen (1984) completely neglect another set of figures, those -

Mason Williams

City of Ambition: Franklin Roosevelt, Fiorello La Guardia, and the Making of New Deal New York Mason Williams Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Mason Williams All Rights Reserved Abstract City of Ambition: Franklin Roosevelt, Fiorello La Guardia, and the Making of New Deal New York Mason Williams This dissertation offers a new account of New York City’s politics and government in the 1930s and 1940s. Focusing on the development of the functions and capacities of the municipal state, it examines three sets of interrelated political changes: the triumph of “municipal reform” over the institutions and practices of the Tammany Hall political machine and its outer-borough counterparts; the incorporation of hundreds of thousands of new voters into the electorate and into urban political life more broadly; and the development of an ambitious and capacious public sector—what Joshua Freeman has recently described as a “social democratic polity.” It places these developments within the context of the national New Deal, showing how national officials, responding to the limitations of the American central state, utilized the planning and operational capacities of local governments to meet their own imperatives; and how national initiatives fed back into subnational politics, redrawing the bounds of what was possible in local government as well as altering the strength and orientation of local political organizations. The dissertation thus seeks not only to provide a more robust account of this crucial passage in the political history of America’s largest city, but also to shed new light on the history of the national New Deal—in particular, its relation to the urban social reform movements of the Progressive Era, the long-term effects of short-lived programs such as work relief and price control, and the roles of federalism and localism in New Deal statecraft. -

Economics During the Lincoln Administration

4-15 Economics 1 of 4 A Living Resource Guide to Lincoln's Life and Legacy ECONOMICS DURING THE LINCOLN ADMINISTRATION War Debt . Increased by about $2 million per day by 1862 . Secretary of the Treasury Chase originally sought to finance the war exclusively by borrowing money. The high costs forced him to include taxes in that plan as well. Loans covered about 65% of the war debt. With the help of Jay Cooke, a Philadelphia banker, Chase developed a war bond system that raised $3 billion and saw a quarter of middle class Northerners buying war bonds, setting the precedent that would be followed especially in World War II to finance the war. Morrill Tariff Act (1861) . Proposed by Senator Justin S. Morrill of Vermont to block imported goods . Supported by manufacturers, labor, and some commercial farmers . Brought in about $75 million per year (without the Confederate states, this was little more than had been brought in the 1850s) Revenue Act of 1861 . Restored certain excise tax . Levied a 3% tax on personal incomes higher than $800 per year . Income tax first collected in 1862 . First income tax in U. S. history The Legal Tender Act (1862) . Issued $150 million in treasury notes that came to be called greenbacks . Required that these greenbacks be accepted as legal tender for all debts, public and private (except for interest payments on federal bonds and customs duties) . Investors could buy bonds with greenbacks but acquire gold as interest United States Note (Greenback). EarthLink.net. 18 July 2008 <http://home.earthlink.net/~icepick119/page11.html> Revenue Act of 1862 Office of Curriculum & Instruction/Indiana Department of Education 09/08 This document may be duplicated and distributed as needed. -

The Civilian Impact of Drone Strikes

THE CIVILIAN IMPACT OF DRONES: UNEXAMINED COSTS, UNANSWERED QUESTIONS Acknowledgements This report is the product of a collaboration between the Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School and the Center for Civilians in Conflict. At the Columbia Human Rights Clinic, research and authorship includes: Naureen Shah, Acting Director of the Human Rights Clinic and Associate Director of the Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School, Rashmi Chopra, J.D. ‘13, Janine Morna, J.D. ‘12, Chantal Grut, L.L.M. ‘12, Emily Howie, L.L.M. ‘12, Daniel Mule, J.D. ‘13, Zoe Hutchinson, L.L.M. ‘12, Max Abbott, J.D. ‘12. Sarah Holewinski, Executive Director of Center for Civilians in Conflict, led staff from the Center in conceptualization of the report, and additional research and writing, including with Golzar Kheiltash, Erin Osterhaus and Lara Berlin. The report was designed by Marla Keenan of Center for Civilians in Conflict. Liz Lucas of Center for Civilians in Conflict led media outreach with Greta Moseson, pro- gram coordinator at the Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School. The Columbia Human Rights Clinic and the Columbia Human Rights Institute are grateful to the Open Society Foundations and Bullitt Foundation for their financial support of the Institute’s Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, and to Columbia Law School for its ongoing support. Copyright © 2012 Center for Civilians in Conflict (formerly CIVIC) and Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America. Copies of this report are available for download at: www.civiliansinconflict.org Cover: Shakeel Khan lost his home and members of his family to a drone missile in 2010. -

MARCEL CADIEUX, the DEPARTMENT of EXTERNAL AFFAIRS, and CANADIAN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS: 1941-1970

MARCEL CADIEUX, the DEPARTMENT of EXTERNAL AFFAIRS, and CANADIAN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS: 1941-1970 by Brendan Kelly A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Brendan Kelly 2016 ii Marcel Cadieux, the Department of External Affairs, and Canadian International Relations: 1941-1970 Brendan Kelly Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto 2016 Abstract Between 1941 and 1970, Marcel Cadieux (1915-1981) was one of the most important diplomats to serve in the Canadian Department of External Affairs (DEA). A lawyer by trade and Montreal working class by background, Cadieux held most of the important jobs in the department, from personnel officer to legal adviser to under-secretary. Influential as Cadieux’s career was in these years, it has never received a comprehensive treatment, despite the fact that his two most important predecessors as under-secretary, O.D. Skelton and Norman Robertson, have both been the subject of full-length studies. This omission is all the more glaring since an appraisal of Cadieux’s career from 1941 to 1970 sheds new light on the Canadian diplomatic profession, on the DEA, and on some of the defining issues in post-war Canadian international relations, particularly the Canada-Quebec-France triangle of the 1960s. A staunch federalist, Cadieux believed that French Canadians could and should find a place in Ottawa and in the wider world beyond Quebec. This thesis examines Cadieux’s career and argues that it was defined by three key themes: his anti-communism, his French-Canadian nationalism, and his belief in his work as both a diplomat and a civil servant. -

"The New Deal of War"

"The New Deal of War" By Torbjlarn SirevAg University of Oslo Half a year beforeJapanese pilots bombed the United States into World War 11, in a June 1941 edition of Coronet magazine, a little known author added his voice to that of other critics of the policies of Franklin D. Roosevelt. There were basically only two New Deals, John Pritchard here retorted to those who were debating the many twists and turns of the administration's policies. As he saw it, there had been a visionary and planning-oriented first stage-a "New Deal I" -from 1933 to the Nazi push into Holland in May 1940. Roughly at that time, however, the first stage had given way to a far more hardnosed phase which he labeled "New Deal I1- the New Deal of War." If Pritchard's phrase was new, the notion behind it was not. But his was and remains the most poignant expression of an attitude that for all its impact has never been fully understood. How can it be that even if a clear majority of the American people favored all steps short of war in the months immediately before Pearl Harbor the President hesitated to take the lead ?And how can it be explaineed that Washington remained in a state of political turmoil during most of the military emergency when other nations at this crucial moment set aside politics in a show of real national unity? In both situations, the corrosive influence of the "New Deal of War" idea remains crucial. In retrospect, this idea served the function as a bridge uniting the peacetime and wartime opposition against Roosevelt. -

RESTORING the LOST ANTI-INJUNCTION ACT Kristin E

COPYRIGHT © 2017 VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW ASSOCIATION RESTORING THE LOST ANTI-INJUNCTION ACT Kristin E. Hickman* & Gerald Kerska† Should Treasury regulations and IRS guidance documents be eligible for pre-enforcement judicial review? The D.C. Circuit’s 2015 decision in Florida Bankers Ass’n v. U.S. Department of the Treasury puts its interpretation of the Anti-Injunction Act at odds with both general administrative law norms in favor of pre-enforcement review of final agency action and also the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the nearly identical Tax Injunction Act. A 2017 federal district court decision in Chamber of Commerce v. IRS, appealable to the Fifth Circuit, interprets the Anti-Injunction Act differently and could lead to a circuit split regarding pre-enforcement judicial review of Treasury regulations and IRS guidance documents. Other cases interpreting the Anti-Injunction Act more generally are fragmented and inconsistent. In an effort to gain greater understanding of the Anti-Injunction Act and its role in tax administration, this Article looks back to the Anti- Injunction Act’s origin in 1867 as part of Civil War–era revenue legislation and the evolution of both tax administrative practices and Anti-Injunction Act jurisprudence since that time. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 1684 I. A JURISPRUDENTIAL MESS, AND WHY IT MATTERS ...................... 1688 A. Exploring the Doctrinal Tensions.......................................... 1690 1. Confused Anti-Injunction Act Jurisprudence .................. 1691 2. The Administrative Procedure Act’s Presumption of Reviewability ................................................................... 1704 3. The Tax Injunction Act .................................................... 1707 B. Why the Conflict Matters ....................................................... 1712 * Distinguished McKnight University Professor and Harlan Albert Rogers Professor in Law, University of Minnesota Law School.