Aesops Fables Free Ebook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

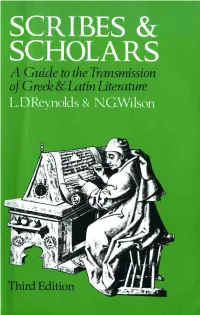

Scribes and Scholars (3Rd Ed. 1991)

SCRIBES AND SCHOLARS A Guide to the Transmission of Greek and Latin Literature BY L. D. REYNOLDS Fellow and Tutor of Brasenose College, Oxford AND N. G. WILSON Fellow and Tutor of Lincoln College, Oxford THIRD EDITION CLARENDON PRESS • OXFORD Oxford University Press, Walton Street, Oxford 0x2 6DP Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bombay Calcutta Cape Town Dares Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madras Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi Paris Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Oxford is a trade mark of Oxford University Press Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Oxford University Press 1968, 1974, 1991 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press. Within the UK, exceptions are allowed in respect of any fair dealing for the purpose of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of the licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside these terms and in other countries should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Scribes and scholars: a guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin literature/by L. -

Aesop's Fables

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/11339/11339-h/11339-h.htm AESOP'S FABLES THE FOX AND THE GRAPES A hungry Fox saw some fine bunches of Grapes hanging from a vine that was trained along a high trellis, and did his best to reach them by jumping as high as he could into the air. But it was all in vain, for they were just out of reach: so he gave up trying, and walked away with an air of dignity and unconcern, remarking, "I thought those Grapes were ripe, but I see now they are quite sour." THE GOOSE THAT LAID THE GOLDEN EGGS A Man and his Wife had the good fortune to possess a Goose which laid a Golden Egg every day. Lucky though they were, they soon began to think they were not getting rich fast enough, and, imagining the bird must be made of gold inside, they decided to kill it in order to secure the whole store of precious metal at once. But when they cut it open they found it was just like any other goose. Thus, they neither got rich all at once, as they had hoped, nor enjoyed any longer the daily addition to their wealth. Much wants more and loses all. THE CAT AND THE MICE There was once a house that was overrun with Mice. A Cat heard of this, and said to herself, "That's the place for me," and off she went and took up her quarters in the house, and caught the Mice one by one and ate them. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

SMATHERS LIBRARIES’ LATIN AND GREEK RARE BOOKS COLLECTION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS page LECTORI: TO THE READER ........................................................................................ 20 LATIN AUTHORS.......................................................................................................... 24 Ammianus ............................................................................................................... 24 Title: Rerum gestarum quae extant, libri XIV-XXXI. What exists of the Histories, books 14-31. ................................................................................. 24 Apuleius .................................................................................................................. 24 Title: Opera. Works. ......................................................................................... 24 Title: L. Apuleii Madaurensis Opera omnia quae exstant. All works of L. Apuleius of Madaurus which are extant. ....................................................... 25 See also PA6207 .A2 1825a ............................................................................ 26 Augustine ................................................................................................................ 26 Title: De Civitate Dei Libri XXII. 22 Books about the City of God. ..................... 26 Title: Commentarii in Omnes Divi Pauli Epistolas. Commentary on All the Letters of Saint Paul. .................................................................................... -

Epigraphical Research and Historical Scholarship, 1530-1603

Epigraphical Research and Historical Scholarship, 1530-1603 William Stenhouse University College London A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the Ph.D degree, December 2001 ProQuest Number: 10014364 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10014364 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis explores the transmission of information about classical inscriptions and their use in historical scholarship between 1530 and 1603. It aims to demonstrate that antiquarians' approach to one form of material non-narrative evidence for the ancient world reveals a developed sense of history, and that this approach can be seen as part of a more general interest in expanding the subject matter of history and the range of sources with which it was examined. It examines the milieu of the men who studied inscriptions, arguing that the training and intellectual networks of these men, as well as the need to secure patronage and the constraints of printing, were determining factors in the scholarship they undertook. It then considers the first collections of inscriptions that aimed at a comprehensive survey, and the systems of classification within these collections, to show that these allowed scholars to produce lists and series of features in the ancient world; the conventions used to record inscriptions and what scholars meant by an accurate transcription; and how these conclusions can influence our attitude to men who reconstructed or forged classical material in this period. -

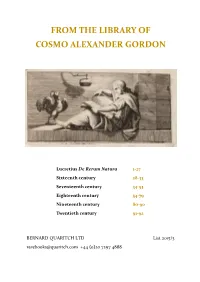

From the Library of Cosmo Alexander Gordon

FROM THE LIBRARY OF COSMO ALEXANDER GORDON Lucretius De Rerum Natura 1-27 Sixteenth century 28-33 Seventeenth century 34-53 Eighteenth century 54-79 Nineteenth century 80-90 Twentieth century 91-92 BERNARD QUARITCH LTD List 2015/3 [email protected] +44 (0)20 7297 4888 Introduction by Nicolas Barker ‘Cosmo and I found our tastes and interests were always in harmony and I came to love his particular sense of humour and gentle goodness, as well as to respect his unusual style of scholarship and general culture.’ So wrote his life-long friend, Geoffrey Keynes in The Gates of Memory. All those who knew him shared the same feeling of calm and contentment, leavened by humour, in his company. Something of this radiates from this residue of a collection of books, never large but put together with a discrimination, a sense of the sum of all the properties of any book, that give it a special quality. Cosmo Alexander Gordon was born on 23 June 1886, the son of Arthur and Caroline Gordon of Ellon, Aberdeen. Ellon Castle was a modest late medieval building, with eighteenth-century additions and yew avenue, the river Ythan running by, where Cosmo fished for salmon and sea-trout. Dr Johnson stayed there in 1773 and admired the local antiquities. So did Cosmo; his taste had extended to medieval manuscripts before he left Rugby for King’s in 1904, where it was nurtured by M. R. James. Although Keynes had also been at Rugby, they did not meet until both were at Cambridge, where Gordon introduced his new friend to David’s book-stall and seventeenth-century literature; they shared a passion for Browne and Fuller. -

LOCATING El GRECO in LATE SIXTEENTH-CENTURY

View metadata, citation and similarbroughtCORE papers to you at by core.ac.uk provided by Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses LOCATING El GRECO IN LATE SIXTEENTH‐CENTURY ROME: ART and LEARNING, RIVALRY and PATRONAGE Ioanna Goniotaki Department of History of Art, School of Arts Birkbeck College, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, July 2017 -1- Signed declaration I declare that the work presented in the thesis is my own Ioanna Goniotaki -2- ABSTRACT Much has been written about the artistic output of Domenicos Theotocopoulos during his time in Spain, but few scholars have examined his works in Venice and even fewer have looked at the years he spent in Rome. This may be in part attributed to the lack of firm documentary evidence regarding his activities there and to the small corpus of works that survive from his Italian period, many of which are furthermore controversial. The present study focuses on Domenicos’ Roman years and questions the traditional notion that he was a spiritual painter who served the principles of the Counter Reformation. To support such a view I have looked critically at the Counter Reformation, which I consider more as an amalgam of diverse and competitive institutions and less as an austere movement that strangled the freedom of artistic expression. I contend, moreover, that Domenicos’ acquaintance with Cardinal Alessandro Farnese’s librarian, Fulvio Orsini, was seminal for the artist, not only because it brought him into closer contact with Rome’s most refined circles, but principally because it helped Domenicos to assume the persona of ‘pictor doctus’, the learned artist, following the example of another of Fulvio’s friends, Pirro Ligorio. -

Fables & Fablebooks

Fables & fablebooks Fables & Fablebooks e-catalogue Jointly offered for sale by: Extensive descriptions and images available on request All offers are without engagement and subject to prior sale. All items in this list are complete and in good condition unless stated otherwise. Any item not agreeing with the description may be returned within one week after receipt. Prices are EURO (€). Postage and insurance are not included. VAT is charged at the standard rate to all EU customers. EU customers: please quote your VAT number when placing orders. Preferred mode of payment: in advance, wire transfer or bankcheck. Arrangements can be made for MasterCard and VisaCard. Ownership of goods does not pass to the purchaser until the price has been paid in full. General conditions of sale are those laid down in the ILAB Code of Usages and Customs, which can be viewed at: <http://www.ilab.org/eng/ilab/code.html> New customers are requested to provide references when ordering. Orders can be sent to either firm. Antiquariaat FORUM BV ASHER Rare Books Tuurdijk 16 Tuurdijk 16 3997 MS ‘t Goy 3997 MS ‘t Goy The Netherlands The Netherlands Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 E–mail: [email protected] E–mail: [email protected] Web: www.forumrarebooks.com Web: www.asherbooks.com www.forumislamicworld.com cover image: no. 17 v 1.0 · 18 March 2020 Second edition of the first printed version of Cinderella, with 6 other stories, all with new and better woodcut illustrations 1. -

118599-11304.Pdf

AESOP’S FABLES Translated by V. S. Vernon Jones With illustrations by Arthur Rackham and others Hand-coloured by Barbara Frith With an afterword by Anna South M MACMILLAN COLLECTOR’S LIBRARY This selection of Aesop's Fables first published 1912 This edition first published by Collector’s Library 2014 Reissued by Macmillan Collector’s Library 2017 an imprint of Pan Macmillan 20 New Wharf Road, London ni 9RR Associated companies throughout the world www. panmacmillan. com isbn 978-1-5098-4436-4 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. 135798642 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Casing design and endpaper pattern by Andrew Davidson Typeset by Bookcraft Ltd, Stroud, Gloucestershire Printed and bound in China by Imago This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. Visit www.panmacmillan.com to read more about all our books and to buy them. You will also find features, author interviews and news of any author events, and you can sign up for e-newsletters so that you’re always first to hear about our new releases. -

Leonardo's Literary Writings

Leonardo’s Literary Writings: History, Genre, Philosophy by Filomena Calabrese A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Italian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Filomena Calabrese, 2011 Leonardo’s Literary Writings: History, Genre, Philosophy Filomena Calabrese Doctor of Philosophy Department of Italian Studies University of Toronto 2011 ABSTRACT: This dissertation examines Leonardo da Vinci’s literary writings, namely those known as the Bestiario, Favole, Facezie, and Profezia, as compelling expressions of how Leonardo envisioned the role and influence of morality in human life. Through an analysis of these four literary collections from the perspective of their genre history, literariness, and philosophical dimension, it aims to bring to light the depth with which Leonardo reflected upon the human condition. The Bestiario, Favole, Facezie, and Profezia are writings that have considerable literary value in their own right but can also be examined in a wider historical, literary, and philosophical context so as to reveal the ethical ideas that they convey. By studying them from a historical perspective, it is possible to contextualize Leonardo’s four collections within the tradition of their respective genres (the bestiary, fable, facetia, and riddle) and thus recognize their adherence as well as contribution to these traditions. The literary context brings to light Leonardo’s intentionality and ingenuity as a writer who uses generic conventions in order to voice his ethical views. Assessed from a philosophical standpoint, these four literary collections prove to be meaningful reflections on the moral state of humanity, thereby justifying the characterization of Leonardo as a moral philosopher. -

The End of the Manutius Dynasty, 1597

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by AIR Universita degli studi di Milano The End of the Manutius Dynasty, 1597 Angela Nuovo Homo sine pecunia, imago mortis. With the death of Aldo Manuzio the Younger at fifty years of age in October 1597, the glorious name of the Manutius family disappeared from the world of publishing. The last heir to the dynasty died in Rome, suddenly, leaving a good deal of business unfinished and unsettled. While a large number of scholars have studied his grandfather Aldus, and to a lesser degree Paolo, there has been a lack of interest in the last figure belonging to the family dynasty, no doubt due to the fact that Aldo had a much weaker impact on the world of humanist culture.1 Since the Annales of Renouard, it has been clear that the material legacy of Aldo was located both in Rome and in Venice. He had brought his famous library with him to Rome when he accepted the position of professor of Humaniora at the university. Aldo had left Venice in 1585; but his firm and his bookshop, containing his large collection of books, was still active under the direction of his partner, Niccolò Manassi. Moreover, the Manutius family had apparently strengthened their connections with the Giunti family during the second half of the sixteenth century. Although there were moments of tension between the two firms (one of them concerned the struggle to gain exclusive use of the italic types), it is worth remembering that Tommaso Giunti generously lent his printing types to Paolo 1 The standard point of departure also for the younger Aldo Manuzio is A. -

Locating El Greco in Late Sixteenth-Century Rome : Art and Learning, Rivalry and Patronage

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Locating El Greco in late sixteenth-century Rome : art and learning, rivalry and patronage https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40280/ Version: Public Version Citation: Goniotaki, Ioanna (2017) Locating El Greco in late sixteenth- century Rome : art and learning, rivalry and patronage. [Thesis] (Un- published) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email LOCATING El GRECO IN LATE SIXTEENTH‐CENTURY ROME: ART and LEARNING, RIVALRY and PATRONAGE Ioanna Goniotaki Department of History of Art, School of Arts Birkbeck College, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, July 2017 -1- Signed declaration I declare that the work presented in the thesis is my own Ioanna Goniotaki -2- ABSTRACT Much has been written about the artistic output of Domenicos Theotocopoulos during his time in Spain, but few scholars have examined his works in Venice and even fewer have looked at the years he spent in Rome. This may be in part attributed to the lack of firm documentary evidence regarding his activities there and to the small corpus of works that survive from his Italian period, many of which are furthermore controversial. The present study focuses on Domenicos’ Roman years and questions the traditional notion that he was a spiritual painter who served the principles of the Counter Reformation. To support such a view I have looked critically at the Counter Reformation, which I consider more as an amalgam of diverse and competitive institutions and less as an austere movement that strangled the freedom of artistic expression. -

Pendulum Royh

"Startling insights and perspectives for anyone who wants to be successful now or in the future." - Tony Hsieh, New York limes b<."Slsclling au1hor of Otli\wing H11ppincu and CEO of Z.ppos.com PENDULUM ROYH. WILLIAMS & MICHAELR. DREW How PAST GENERATIONS SHAPE OUR PRESENT AND PREDICT OUR FUTURE Praise for Pendulum “How do you predict what kind of society we’re in? How do you know when’s the right time to make a difference? In Pendulum, Roy H. Williams and Michael R. Drew have combed through history’s ups and downs and the cultural shifts that ripple through every generation. They’ve written a unique guidebook that has an interest- ing perspective for marketers, entrepreneurs, and anyone who is thinking about how to live in the now—and in the future.” —Tony Hsieh, New York Times Best-selling Author of Delivering Happiness, and CEO of Zappos.com “The Pendulum offers fascinating insights into the sur- prises and revelations of shifting social trends throughout 3/505 history. Roy H. Williams and Michael R. Drew answer the age-old question: What makes us tick?” —Harvey Mackay, Author of the #1 New York Times Best Seller, Swim With The Sharks Without Being Eaten Alive How about the following. “Understanding how civilization shifts its mindset on a decadal level is critical to business and governance. In Pendulum, Michael R. Drew and Roy H. Williams have synthesized several thousand years of history and figured out why we’ve acted the way we do. Better yet, they’ve also given us a road map of what it means going forward.