Somalia and Djibouti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History and Epidemiology of Global Smallpox Eradication Smallpox

History and Epidemiology of Global Smallpox Eradication Smallpox Three Egyptian Mummies 1570-1085 BC Ramses the Vth Died 1157 BC Early Written Description of Smallpox India 400 AD “Severe pain is felt in the large and small joints, with cough, shaking, listlessness and langour; the palate, lips, and tongue are dry with thirst and no appetite. The pustules are red, yellow, and white and they are accompanied by burning pain. The form soon ripens …the body has a blue color and seems studded with rice. The pustules become black and flat, are depressed in the centre, with much pain.” Smallpox and History • In the Elephant war in Mecca 568 AD, smallpox decimated the Ethiopian soldiers • Introduction of smallpox into the new world (Carribean 1507, Mexico 1520, Peru 1524, and Brazil 1555 ) facilitated Spanish conquest • Smallpox destroys Hottentots (1713) • In 1738, smallpox killed half the Cherokee Indian population • Smallpox disrupted colonial army in 1776 Smallpox Control Strategies • Smallpox hospitals (Japan 982 AD). • Variolation 10th Century. • Quarantine 1650s. • Home isolation of smallpox in Virginia 1667. • Inoculation and isolation (Haygarth 1793). • Jenner and widespread practice of vaccination throughout Europe and rest of the world. • Mass vaccination. • Surveillance containment. Variolation Inoculation with Smallpox Pus • Observations: – Pocked marked persons never affected with smallpox – Persons inoculated with smallpox pustular fluid or dried scabs usually had milder disease • Not ideal control strategy – Case fatality rate still 2% – Can transmit disease to others during illness The 1st Smallpox Vaccination Jenner 1796 Cowpox lesions on the hand of Sarah Nelmes (case XVI in Jenner’s Inquiry), from which material was taken for the vaccination of James Phipps below in 1796 History of Smallpox Vaccination 1805 Growth of virus on the flank of a calf in Italy. -

East and Central Africa 19

Most countries have based their long-term planning (‘vision’) documents on harnessing science, technology and innovation to development. Kevin Urama, Mammo Muchie and Remy Twingiyimana A schoolboy studies at home using a book illuminated by a single electric LED lightbulb in July 2015. Customers pay for the solar panel that powers their LED lighting through regular instalments to M-Kopa, a Nairobi-based provider of solar-lighting systems. Payment is made using a mobile-phone money-transfer service. Photo: © Waldo Swiegers/Bloomberg via Getty Images 498 East and Central Africa 19 . East and Central Africa Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo (Republic of), Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Kenya, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, Uganda Kevin Urama, Mammo Muchie and Remy Twiringiyimana Chapter 19 INTRODUCTION which invest in these technologies to take a growing share of the global oil market. This highlights the need for oil-producing Mixed economic fortunes African countries to invest in science and technology (S&T) to Most of the 16 East and Central African countries covered maintain their own competitiveness in the global market. in the present chapter are classified by the World Bank as being low-income economies. The exceptions are Half the region is ‘fragile and conflict-affected’ Cameroon, the Republic of Congo, Djibouti and the newest Other development challenges for the region include civil strife, member, South Sudan, which joined its three neighbours religious militancy and the persistence of killer diseases such in the lower middle-income category after being promoted as malaria and HIV, which sorely tax national health systems from low-income status in 2014. -

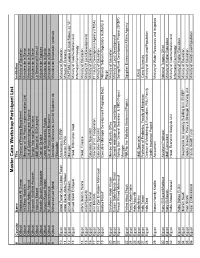

Cairo Workshop Participants

Master Cairo Workshop Participant List # Country Name Title Institution 1 Djibouti Abdourazak Ali Osman Director of Planning Department Ministry of Education 2 Djibouti Ali Sillaye Abdallah Manager of the Project Implementation Unit Ministere de la Sante 3 Djibouti Ammar Abdou Ahmed Dri. of Epidemiology and Hygiene Ministere de la Sante 4 Djibouti Assoweh Abdillahi Assoweh Service Information Sanitaire Ministere de la Sante 5 Djibouti Fatouma Bakard M&E Specialist, SIDA project Le Secretariat Executif 6 Djibouti Housein Doualeh Aboubaker Chef de Service Ministere de Finances 7 Djibouti Hussein Kayad Halane Unite de Gestion de Projets Ministere de la Sante 8 Djibouti M. Abdelrahmane Dir. of Planning and Research Ministere de la Sante 9 Djibouti Mohamed Issé Mahdi Secrétaire Générale du Comité Supérieur de Ministère de l'éducation nationale l'Education 10 Egypt Abdel Fattah Samir Abdel Fattah Accountant, ECEEP Ministry of Education 11 Egypt Abdel Samie Abdel Hafeez Director PPMU Ministry of Economy 12 Egypt Ahmed Abdel Monem Manager PAPFAM, League of Arab States, 22 "A" 13 Egypt Ahmed Saad El Sayed Head, Information Dept. Ministry of Communication and InformationTechnology: 14 Egypt Alfons Ibrahim Hanna Head, Finance Ministry of Education 15 Egypt Amal Sayed Ali Ministry Of Local Development 16 Egypt Amany Kamel Education Specialist Ministry of Education 17 Egypt Amr Mostafa Director of Int. Cooperation IT Industry Development Agency (ITIDA) 18 Egypt Amr Zein El-Abdein Mahmoud Education Specialist Ministry of Education 19 Egypt Bodour Nassif Executive Manager Development Programs Dept. National Telecom Regulatory Authority in Egypt 20 Egypt Ebraheem Abdel Khalek Member of Quality Office Ministry of Education 21 Egypt Essam Galal Hassan Shaat General manager of local monitoring Ministry of Local Development 22 Egypt Farouk Ahmed Mahmoud Sohag Gov. -

Natural Disasters in the Middle East and North Africa

Natural Disasters in Public Disclosure Authorized the Middle East and North Africa: A Regional Overview Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized January 2014 Urban, Social Development, and Disaster Risk Management Unit Sustainable Development Department Middle East and North Africa Natural Disasters in the Middle East and North Africa: A Regional Overview © 2014 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org All rights reserved 1 2 3 4 13 12 11 10 This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundar- ies, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorse- ment or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Recon- struction and Development / The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone: 978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. -

In (Hc Abscncc of Any Other Rcqucst to Speak. the Prc\Idcnt ;\Djourncd The

Part II 25s _-. .-_--.--.-_---. __. -. In (hc abscncc of any other rcqucst to speak. the At ths came meeting. the rcprcsentativc of F-rancc Prc\idcnt ;\djourncd the deb;ltc. sn)ing th<it the Security rcvicucd the background of the matter and stntrd that ( (1unc11 would rcm;rin scilcd of the quc\~~on 50 that II In IIcccmbcr 1974, the l,rcnch Government had organ- mlpht rc\umc con~ldcrntion of it :it any appropriate ~/cd a conhuttation of thz Comorian population which llrne.“‘-“‘ rcsultcd in a large majority in Favour of indcpendencc. Howcvcr. two thirds of the votes in the island of klayotte were negative. The French parliament adopted Decision of 6 I:ebruary 1976 ( IHHXth meeting): rcJcc- on 30 June I975 a law providing for the drafting of a lion of c-Power draft resolution constitution prcscrving the political and administrative In a telegram’Oz’ dated 28 January 1976, the Head of rdentit) of the islands. Although only the French State of the Comoros informed the President of the parliament could decide to transfer sovereignty, the Security Council that the French Govcrnmcnt intended Chamber of Deputies of the Comoros proclaimed the TV, organilr a referendum in the island of Mayotte on 8 independence of the island> on 5 July 1975. I’sbruary 1976. tie pointed out that Muyottc was an On 31 Dcccmbcr. the French Government recognired lntcgral part of Comorian territory under French laws the indcpcndcnce of the islands of Grandc-Comore, and that on I2 November 1975, the linitcd Nations had Anjouan. and Mohfli but provided for the pcoplc of admitted the C‘omorian State consisting of the four Mayottc to make a choice between the island remaining lhland:, of Anjouan, Mayottc. -

A New Deal for Somalia? : the Somali Compact and Its Implications for Peacebuilding

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY i CENTER ON INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION A New Deal for Somalia? : The Somali Compact and its Implications for Peacebuilding Sarah Hearn and Thomas Zimmerman July 2014 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY CENTER ON INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION The world faces old and new security challenges that are more complex than our multilateral and national institutions are currently capable of managing. International cooperation is ever more necessary in meeting these challenges. The NYU Center on International Cooperation (CIC) works to enhance international responses to conflict, insecurity, and scarcity through applied research and direct engagement with multilateral institutions and the wider policy community. CIC’s programs and research activities span the spectrum of conflict, insecurity, and scarcity issues. This allows us to see critical inter-connections and highlight the coherence often necessary for effective response. We have a particular concentration on the UN and multilateral responses to conflict. Table of Contents A New Deal for Somalia? : The Somali Compact and its Implications for Peacebuilding Sarah Hearn and Thomas Zimmerman Introduction 2 The Somali New Deal Compact 3 Process 3 Implementation to Date 5 Trade-offs 6 Process 6 Risks 7 Implementation 8 External Actors’ Perspectives on Trade-offs 9 Somali Actors’ Perspectives on Trade-offs 9 Conclusions 10 Endnotes 11 Acknowledgments 11 Introduction In balancing these trade-offs, we highlight the need for Somalis to articulate priorities (not just programs, but In this brief,1 we analyze the process that led to the also processes) to advance confidence building. Low “Somali New Deal Compact,” the framework’s potential trust among Somalis, and between Somalis and donors, effectiveness as a peacebuilding tool, and potential ways will stymie cooperation on any reform agenda, because to strengthen it. -

Djibouti Bishop Happy That Mogadishu Cathedral Ruins Are Helping Somalis

Djibouti bishop happy that Mogadishu cathedral ruins are helping Somalis NAIROBI, Kenya – Djibouti Bishop Giorgio Bertin, who oversees Catholics in neighboring Somalia, said he is happy that the ruins of Mogadishu’s only Catholic cathedral are housing hundreds of displaced Somalis. “In Mogadishu there are hundreds of camps for displaced people. The cathedral area is one of them,” the bishop said in an email interview. “I think that at least 300 could easily fit in, but I have no real figures.” The U.N. officially has declared a famine in parts of Somalia, including the internally displaced communities in Mogadishu, the Somali capital. More than 100,000 Somalis poured into the capital searching for food within a two-month period this summer. Somalia has had a civil war since 1991, and the famine-hit areas are plagued by a lack of security because of a weak central government and the presence of various political factions that control parts of the country. The instability and resulting violence severely limit the delivery of humanitarian assistance. Hundreds of thousands of Somalis have fled to Kenya. Bishop Bertin said the best solution would be to help the displaced people within Somalia, “but the problem is often that where they are either they are unsafe or we cannot reach them.” In 1989, Italian-born Bishop Pietro Salvatore Colombo of Mogadishu was killed at his cathedral. After the murder, the Vatican eliminated the post and now oversees Somalia through neighboring Djibouti. “The cathedral has not been used since Jan. 9, 1991, when it was ransacked” and set on fire, said Bishop Bertin. -

Land Use Planning Guidelines for Somaliland 2009

Land Use Planning Guidelines for Somaliland Project Report No L-13 March 2009 Somalia Water and Land Information Management Ngecha Road, Lake View. P.O Box 30470-00100, Nairobi, Kenya. Tel +254 020 4000300 - Fax +254 020 4000333, Email: [email protected] Website: http//www.faoswalim.org. Funded by the European Union and implemented by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the SWALIM Project concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This document should be cited as follows: Venema, J.H., Alim, M., Vargas, R.R., Oduori, S and Ismail, A. 2009. Land use planning guidelines for Somaliland. Technical Project Report L-13. FAO-SWALIM, Nairobi, Kenya. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Acronyms ............................................................................................ v Acknowledgments ..........................................................................................vi ABOUT THE GUIDELINES................................................................................ vii 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 1 1.1 What is land use planning?................................................................. 1 1.2 Recent -

SOMALIA RAINFALL and FLOODS UPDATE 02 May 2021

SOMALIA RAINFALL and FLOODS UPDATE 02 May 2021 Due to climate change and its associated impacts Somalia is now recording more wet and dry weather events, often with disastrous consequences for the people facing such extremes. It has become even more difficult to predict such sequential events. Currently, more than 80 percent of the country is facing drought conditions in the mid of the primary Gu rainy season. Yet, flash floods have been reported in the last two days following heavy and sporadic rains in Somaliland. In addition, limited climate change adaptive capacities has led to irresponsible socio- economic practices like cutting of river banks to extract irrigation waters, further exposing the communities to climate hazards. For instance, riverine flooding due to open river banks near Baarey and Moyko villages has been reported in Jowhar within Middle Shabelle region. With current climate models predicting extreme temperatures and rainfall in the future within the region, the country is likely to continue experiencing frequent flood and drought events with likely consequences of affecting untold numbers of people, taxing economies, disrupting food production, creating unrest and prompting migrations. FLOODS AND RAINS UPDATE The Gu rains continued to spread across most parts of the country with Somaliland and Puntland experiencing moderate to heavy rains over the last week. Other areas in central and southern regions recorded light to moderate rains. The Ethiopian highlands received moderate rains within the last week. Since 25 May 2021, most parts of Somaliland have been receiving moderate to heavy rains. Localized flash floods caused by the heavy rainfall were reported on 01 May 2021 in parts of Hargeisa district. -

Minutes for Regional Wash Cluster Meeting

Somalia WASH (Water, Sanitation, Hygiene) CLUSTER MINUTES FOR REGIONAL WASH CLUSTER MEETING Soma AGENDA Date: 19/05/2016 Time: 10:00: am-12:00pm Venue: Ministry of Health Chair: Abdullahinur Kassim Kindly confirm attendance for security access to: Sadia Hussein ([email protected]) and cc: [email protected] Standing items (for every meeting) 1. Introductions (5 min) 2. Review and endorsement of the last cluster meeting minutes and follow up on the action points (10 min) (give updates on the previous action points. NB: all updates should be captured in the meeting minutes) 3. Updates on AWD/cholera and ongoing response in the region 4. Updates on floods in the region and its impact in the affected areas and humanitarian response so far. 5. Ongoing/Planned response by partners (who is doing what, where and when- 4W matrix). 6. WASH gaps and current response. Can they be filled by agencies present in meeting with existing funds? 7. Elections of the District Lead Agencies (DLAs)/ District Focal Points (DFPs)MoHBanadir WASH Coordinator presentation on Regional WASH coordination. 8. Any other challenge or constraint affecting all agencies? Agree action 9. A.O.B File Name: Draft Agenda Banadir/Lower Shabelle meeting, 19th May, 2016 Somalia REGIONAL WASH CLUSTER MINUTES OF THE MEETING – BANADIR AND L/SHABELLE Date: 19/05/2016 Time: 10.00 am-12:00pm Venue: Ministry of Health Chair: AbdullahinurKassim Agenda Summary of discussion Action point Focal Time line point/Agency Introduction The meeting was chaired by Kassim, the WASH cluster regional focal point. It was opened with prayers. The chairman, welcomed the partners and gave them chance of introduction in general. -

Global Effort Pays Off.. Smallpox at Target "Zero"

DXIEIJMECIX: CENTER FOR DISEASE CONTROL ATLANTA, GEORGIA 30333 VOLUME 11, NO. 10 Zero Smallpox Issue This issue of DATELINE: CDC is devoted to the story of the eradi cation of smallpox and CDC's in volvement. Inside stories include: • Historical vignettes • Pictures of field work • The last case of U.S. smallpox • An early campaign to eliminate the disease • Technology of eradication • Future of the smallpox virus • Chronology of smallpox, and others ft#***#*####*#****#*#*********** Throughout this issue are scattered stories o f "unsung heroes" from many nations who worked with CDC staff in V A R IO LA MAJOR'S last case Rahima Banu, AFTER RECOVERY, Ali Maow Maalin, the fight against smallpox. We have a little girl in Bangladesh who survived. will have chance for normal life. asked the staffers who worked with them to write about them, and all Global Effort Pays Off.. represent true stories o f the eradica tion battle. Smallpox at Target "Zero" -ft****************************** The last documented, naturally occurring case of smallpox was diagnosed in Physicians Challenged Merka, Somalia, in 1977. On October 26, 1979, the world celebrated its second anniversary free from smallpox transmission. Smallpox in 1844 A li Maow Maalin, then 23, was a of confidence among a trained army of The WHO campaign against small cook in Somalia when he came down smallpox fighters from most of the pox wasn't the first time war had been with smallpox. When he recovered, nations of the world — confidence that declared on the disease. he became the last recorded case of they could be successful in combat In 1844 the progress of a vaccina variola minor, a less severe form of with an old enemy. -

ROTA NEWS July 25 Th , 2013

ROTA NEWS July 25 th , 2013 Rotary Club of Barbados, Barbados Chartered March 07, 1962 District 7030 Club Officers President Ronald Davis President Elect Ron Davis Vice President Elvin Sealy Secretary Paul Ashby Treasurer Brian Cole Club Service Director R.I Theme 2013-2014 H. Waldo Clarke Vocational Service Director Officers District Officers Jedder Robinson District Governor President Community Service Director Herve Honoré Shawn Franklin Ron Burton District Governor Elect International Service Director President Elect Elwin Atmodimedjo Lisa Cummins Gary C.K. Huang Youth Service Director District Governor Nominee Warren Mottley Milton Inniss Immediate Past President Assistant Governor (Barbados) Anthony Williams Katrina Sam-Prescod Sergeant-At-Arms Alexander McDonald District Grants PDG David Edwards, Chair District Disaster Relief PDG Tony Watkins, Chair The Four Way Test Weekly meetings on Thursdays at Hilton Barbados Of the things we think, say or do Needham’s Point, Aquatic Gap, 1. Is it the TRUTH? St. Michael at 12 noon 2. Is it FAIR to all concerned? 3. Will it build GOODWILL and BETTER P.O. Box 148B, Brittons Hill, FRIENDSHIPS ? St. Michael, Barbados 4. Will it be BENEFICIAL to all concerned? www.clubrunner.ca/barbados Biography Burton has received the RI Service Above Self Award and the Foundation’s Citation for Meritorious Ron D. Burton Service, Distinguished Service Award, and International Service Award for a Polio-Free World. Rotary Club of Norman, Oklahoma, USA, He and his wife, Jetta, are Paul Harris Fellows, President, Rotary International, 2013-14 Benefactors, Major Donors, and members of the Paul Harris, Bequest, and Arch C. Klumph Societies.