The Garden As a Metaphor for Paradise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Islamic Gardens

Islamic Gardens Amy Rebecca Gansell This course explores gardens of the Islamic World, covering a breadth of historical, cultural, geographic, and environmental contexts. After being introduced to the Islamic world, the nature of specifically “Islamic” gardens is considered. While formal design and aesthetic experience is emphasized throughout, religious, social, and political implication of landscape design are studied through historic cases. Evidence for past gardens, archaeology, and garden conservation are addressed as well. Week 1 Introduction to Islamic culture, religion, and history Students are encouraged to browse entire books, outlining major themes. These books may be consulted for reference throughout the semester. -R. Hillenbrand, Islamic Art and Architecture (Thames and Hudson, 1999). -Ira Lapidus, A History of Islamic Societies (Cambridge, 2002). -Frederick Mathewson Denny, An Introduction to Islam, 3rd edition (Prentice Hall, 2005). Week 2 Introduction to Islamic gardens, Part 1: History and Symbolism -J. Lehrman, “An introduction to the problems and possibilities of restoring historic Islamic gardens,” in L. Tjon Sie Fat and E. de Jong (eds.), The Authentic Garden: A Symposium on Gardens (Leiden: Clusius Foundation, 1990). -Emma Clark, “Introduction” and Ch. 1 “History, symbolism, and the Quran,” in The Art of the Islamic Garden (Wiltshire, UK: Crowood Press, 2004), pp. 11-22, 23-36. Week 3 Introduction to Islamic gardens, Part 2: Design and Layout -David Stronach, “Parterres and stone watercourses at Pasargadae: Notes on the Achaemenid contribution to garden design,” Journal of Garden History 14 (1994): 3-12. -Emma Clark, Ch. 2 “Design and Layout” and Ch. 3 “Geometry, hard landscaping and architectural ornament,” in The Art of the Islamic Garden (Wiltshire, UK: Crowood Press, 2004), pp. -

Introduction Everyday Coexistence in the Post-Ottoman Space

Introduction Everyday Coexistence in the Post-Ottoman Space REBECCA BRYANT In 1974 they started tormenting us, for instance we’d pick our apples and they’d come and take them right out of our hands. Because we had property we held on as long as we could, we didn’t want to leave, but fi nally we were afraid of being killed and had to fl ee. … We weren’t able to live there, all night we would stand by the windows waiting to see if they were going to kill us. … When we went to visit [in 2003, after the check- points dividing the island opened], they met us with drums as though nothing had happened. In any case the older elderly people were good, we used to get along with them. We would eat and drink together. —Turkish Cypriot, aged 89, twice displaced from a mixed village in Limassol district, Cyprus In a sophisticated portrayal of the confl ict in Cyprus in the 1960s, Turkish Cypriot director Derviş Zaim’s feature fi lm Shadows and Faces (Zaim 2010) shows the degeneration of relations in one mixed village into intercommunal violence. Zaim is himself a displaced person, and he based his fi lm on his extended family’s experiences of the confl ict and on information gathered from oral sources. Like anthropologist Tone Bringa’s documentary We Are All Neighbours (Bringa 1993), fi lmed at the beginning of the Yugoslav War and showing in real time the division of a village into warring factions, Zaim’s fi lm emphasizes the anticipa- tion of violence and attempts to show that many people, under the right circumstances, could become killers. -

MJMES Volume VIII

Volume VIII 2005-2006 McGill Journal of Middle East Studies Revue d’études du Moyen-Orient de McGill MCGILL JOURNAL OF MIDDLE EAST STUDIES LA REVUE D’ÉTUDES DU MOYEN- ORIENT DE MCGILL A publication of the McGill Middle East Studies Students’ Association Volume VIII, 2005-2006 ISSN 1206-0712 Cover photo by Torie Partridge Copyright © 2006 by the McGill Journal of Middle East Studies A note from the editors: The Mandate of the McGill Journal of Middle East Studies is to demonstrate the dynamic variety and depth of scholarship present within the McGill student community. Staff and contributors come from both the Graduate and Undergraduate Faculties and have backgrounds ranging from Middle East and Islamic Studies to Economics and Political Science. As in previous issues, we have attempted to bring this multifaceted approach to bear on matters pertinent to the region. *** The McGill Journal of Middle East Studies is registered with the National Library of Canada (ISSN 1206-0712). We have regularized the subscription rates as follows: $15.00 Canadian per issue (subject to availability), plus $3.00 Canadian for international shipping. *** Please address all inquiries, comments, and subscription requests to: The McGill Journal of Middle East Studies c/o MESSA Stephen Leacock Building, Room 414 855 Sherbrooke Street West Montreal, Quebec H3A 2T7 Editors-in-chief Aliza Landes Ariana Markowitz Layout Editor Ariana Markowitz Financial Managers Morrissa Golden Avigail Shai Editorial Board Kristian Chartier Laura Etheredge Tamar Gefen Morrissa Golden -

The Mosque of the Turkish Grand National Assembly in Ankara: Breaking with Tradition

MOHAMMAD AL-ASAD THE MOSQUE OF THE TURKISH GRAND NATIONAL ASSEMBLY IN ANKARA: BREAKING WITH TRADITION The mosque of the Turkish Grand National Assem- hall is represented only by a set of steps that rises to bly in Ankara, designed by the Turkish father-and- about one meter.' These digressions from, or rejec- son team of Behruz and Can Cinici, represents a sig- tions of, past prototypes are most unusual even in a nificant departure from the usual conception of contemporary mosque design. Far from being the mosque architecture, both past and present, in its result of ignoring the past, however, a study of the clear rejection of elements that have traditionally been mosque reveals a serious analysis of the numerous associated with the mosque (fig. 1): the traditional traditions of mosque architecture. The design also dome and minaret are absent; the traditionally solid raises questions about the role of a mosque in the qibla wall is in their design replaced by a glazed sur- legislative complex of a country which, since the face that opens onto a garden; and the separation 1920's, has had a majority Muslim population, but a between the men's and women's areas in its prayer secular system of government.2 . · .... i-..-,... -. Fig. 1. Ankara. Mosque of the Turkish Grand National Assembly. General view. (Photo: from C. C. Davidson and . Serageldin, eds., Architecture Beyond Architecture, p. 126) 156 MOHAMMAD AL-ASAD Fig. 2. Ankara. Turkish Grand National Assembly complex. General view: The mosque is located to the south of the complex, and the Public Relations Buildings are located to the north of the mosque. -

If Angels Do Not Have a Gender Then How Come They Have Boys Names?

If angels do not have a gender then how come they have boys names? It is true that we believe that angels do not have gender. Angels unlike human beings are pure spirit. This is why when people say that a human being has become an angel in heaven that is incorrect. Any human being in heaven is a saint. It is true that human beings until the resurrection of the dead while in heaven only contain their spiritual nature. But when Christ comes again, and the resurrection of the dead occurs at that moment human beings will become complete joining the physical and spiritual together in heaven. Hence, angels and human beings are not simply a different species they are different order of creation. As such angels can never become human and humans can never become angels. But when angels have been revealed to human beings, they taken on the appearance of somewhat human form. They did this in order for human beings to be able to comprehend the message that is being given to them from God. The word angel means messenger. And each angel has a specific function to perform based on their rank. There are nine ranks of angels: Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones, Dominions, Virtues, Powers, Principalities, Archangels and Angels. Seraphim are caretakers to the throne of God and lead the worship of God in heaven. Cherubim guard the tree of life and the throne of God. Thrones are living symbols of God’s justice and authority and listening to the will of God present the prayers of human beings to Him. -

Visions Beyond the Veil by HA Baker

Visions Beyond the Veil H.A. Baker Copyright © 2017 GodSounds, Inc. All rights reserved. ISBN: 1544127588 ISBN-13: 978-1544127583 For more information on our voiceover services and to see our online store of Christian audio-books go to GodSounds.com OTHER BOOKS AVAILABLE BY GODSOUNDS, INC. Like Precious Faith by Smith Wigglesworth Divine Healing: A Gift from God by John G Lake Intimacy with Jesus: Verse by Verse from the Song of Songs by Madame Guyon A Plain Account of Christian Perfection by John Wesley Finney Gold: Words that Helped Birth Revival by Charles Finney Closer to God by Meister Eckhart The Letters of Ignatius by Ignatius The printing of this book is dedicated to Rolland & Heidi Baker, as I believe that H.A. Baker is proud of them and rooting them on - even now. CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................. 3 CH 1 - MIGHTY OUTPOURING OF THE HOLY SPIRIT.................................... 11 CH 2 - SUPERNATURAL MANIFESTAIONS OF THE HOLY SPIRIT ............. 17 CH 3 - SCRIPTURAL RESULTS OF THE OUTPOURING .................................. 23 CH 4 - VISIONS OF HEAVEN .................................................................................... 33 CH 5 - PARADISE ........................................................................................................ 43 CH6 - ANGELS IN OUR MIDST ................................................................................ 51 CH 7 - THE KINGDOM OF THE DEVIL ................................................................ -

Role of the Muslim Anjumans for the Promotion of Education in the Colonial Punjab: a Historical Analysis

Bulletin of Education and Research December 2019, Vol. 41, No. 3 pp. 1-18 Role of the Muslim Anjumans for the Promotion of Education in the Colonial Punjab: A Historical Analysis Maqbool Ahmad Awan* __________________________________________________________________ Abstract This article highlightsthe vibrant role of the Muslim Anjumans in activating the educational revival in the colonial Punjab. The latter half of the 19th century, particularly the decade 1880- 1890, witnessed the birth of several Muslim Anjumans (societies) in the Punjab province. These were, in fact, a product of growing political consciousness and desire for collective efforts for the community-betterment. The Muslims, in other provinces, were lagging behind in education and other avenues of material prosperity. Their social conditions were also far from being satisfactory. Religion too had become a collection of rites and superstitions and an obstacle for their educational progress. During the same period, they also faced a grievous threat from the increasing proselytizing activities of the Christian Missionary societies and the growing economic prosperity of the Hindus who by virtue of their advancement in education, commerce and public services, were emerging as a dominant community in the province. The Anjumans rescued the Muslim youth from the verge of what then seemed imminent doom of ignorance by establishing schools and madrassas in almost all cities of the Punjab. The focus of these Anjumans was on both secular and religious education, which was advocated equally for both genders. Their trained scholars confronted the anti-Islamic activities of the Christian missionaries. The educational development of the Muslims in the Colonial Punjab owes much to these Anjumans. -

Lesson 7A FINAL (GENERAL Or LAST) JUDGMENT

Lesson 7A FINAL (GENERAL or LAST) JUDGMENT Beloved Father of Mercy and Justice, We Your children, offer our lives as a pure and holy sacrifice, uniting our lives and our death to the life and death of Your Son and our Savior. At the Final Judgment we will stand united with the Body of Christ, body and soul, to receive Your Son's judgment. We will face this last and definitive judgment unafraid as the Books of Works are opened to reveal the imperishable deeds of love and mercy accumulated by the Church. This is the treasure stored up for eternity which Your children offer in the name of Christ our Savior and Redeemer. Send Your Holy Spirit, Lord, to lead us in this lesson of our study on the Eight Last Things. We pray in the name of God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Amen. + + + While I was watching thrones were set in place and one most venerable took his seat. His robe was white as snow, the hair of his head as pure as wool. His throne was a blaze of flames; its wheels were a burning fire. A stream of fire poured out, issuing from his presence. A thousand thousand waited on him, ten thousand times ten thousand stood before him. The court was in session and the books lay open. Daniel 7:9-10 For as the Father has life in himself, so he has granted the Son also to have life in himself; and, because he is the Son of man, has granted him power to give judgment. -

Desert Utopia: the Hidden Unity of Iranian Architecture Conceptualization Behind the Making of a Documentary Film

American International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 4 No. 2; April 2018 Desert Utopia: The Hidden Unity of Iranian Architecture Conceptualization behind the Making of a Documentary Film Khosrow Bozorgi Professor of Architecture and Urban Design Director, Center for Middle Eastern Architecture and Culture College of Architecture, University of Oklahoma United States of America NARRATIVE Desert Utopia will examine the history of architecture in three desert cities in Iran, exploring unique aspects of the built environment that enabled people to flourish in one of the world’s harshest climates. Although the film will focus on the history of Iranian desert architecture spanning thousands of years, this project is nevertheless timely for today’s American audiences. Due to concerns about global environmental change, sustainable building techniques have emerged as a topic of increasing interest over the past two decades. This interest encompasses themes such as the use of local building materials, creative ways to minimize water use (and water waste), and ways to reduce the amount of energy spent on heating and cooling. Furthermore, the geopolitics of the last two decades also have piqued Americans’ curiosity about the Middle East, especially Iran, but for many people, their knowledge about this part of the world is spotty or even misinformed. Desert Utopia is therefore a film that comes at the right time: It will help satisfy Americans’ curiosity about environmentally sound architecture while filling some of the gaps in their knowledge about Iranian culture and history. However, Desert Utopia is more than simply a film about sustainable architecture in Iranian history. -

The Meaning of Landscape in Classical Arabo-Muslim Culture

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography, No.196, 16 October 2001 The Meaning of Landscape in Classical Arabo-Muslim Culture Lamia LATIRI Summary: This article explores the concept of landscape in Arabo-Muslim culture from a linguistic and literary standpoint1. Based on extracts from historical collections produced by Arab geographers of the classical period, it shows the existence of spatial landscape models and stereotypes that served to situate a place in a landscape. The landscapes are found to be defined on visual, aesthetic and sensory criteria. Key words: lexicology, landscape, Muslim culture A constant feature of human culture is a capacity to absorb extremely varied influences. At different times in history, the Christian West and Muslim East have established relations and influenced each other. The common core to both Muslim and Western science is the scientific legacy of Ancient Greece2. The series of studies and translations of Greek scientific works, begun in the Omayyad and Abbasid era at the end of the eighth century, and continued in Spain (Cordoba) in the twelfth century, proved valuable for Christian Europe between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries3. It is therefore not surprising to see a formulation of landscape emerge at the start of the fifteenth century in the West. It was a logical process consequent on the transmission, assimilation and renewal of the philosophy and science of the Ancient world. At the end of a long and complex process, Western culture formulated its theories and interpretations of landscape, and directed them in a way that gave a central place to the visual and scene-setting aspects. -

W Rings a Ne Reen W Or

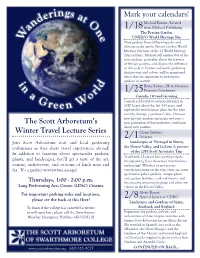

erings at Mark your calendars! d O Michael Brown, Retired n 1/18 from Medical Publishing a n The Persian Garden W e UNESCO World Heritage Site Nine gardens from different epochs and climates make up the Persian Garden World Heritage Site (one of the 21 World Heritage Sites in Iran). Michael will explore five of the nine gardens, generalize about the features of Persian gardens, and discuss the influence of this style in Iranian and world gardening. Architecture and culture will be mentioned when they are important to viewing the i gardens in context. n d Becky Robert, PR & Volunteer rl 1/25Programs Coordinator a o Canada: 150 and Growing G Canada celebrated its sesquicentennial in r W 2017. Learn about the last 150 years, and ee n explore the revitalization plans for the next century through a gardener’s lens. Discover how historic gardens and parks welcome a The Scott Arboretum’s new generation of horticulturists, and learn about new gardens. Winter Travel Lecture Series Claire Sawyers, 2/1 Director Join Scott Arboretum staff and local gardening Landscapes of Portugal in Sintra, enthusiasts as they share travel experiences abroad! the Douro Valley, and Lisbon: A preview of the 2018 Scott Associates Trip In addition to learning about spectacular gardens, Travel with Claire on her scouting trip for plants, and landscapes, you’ll get a taste of the art, the upcoming Scott Associates international cuisine, architecture, and customs of lands near and garden trip! Whether or not you are far. It’s a perfect wintertime escape! considering going on the trip, come see some spectacular palace gardens, unique places and garden features, cork oak forests, and Thursdays, 1:00 - 2:00 p.m. -

Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology

The Ruins of Paradise: Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology by Matthew M. Newman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Richard Janko, Chair Professor Sara L. Ahbel-Rappe Professor Gary M. Beckman Associate Professor Benjamin W. Fortson Professor Ruth S. Scodel Bind us in time, O Seasons clear, and awe. O minstrel galleons of Carib fire, Bequeath us to no earthly shore until Is answered in the vortex of our grave The seal’s wide spindrift gaze toward paradise. (from Hart Crane’s Voyages, II) For Mom and Dad ii Acknowledgments I fear that what follows this preface will appear quite like one of the disorderly monsters it investigates. But should you find anything in this work compelling on account of its being lucid, know that I am not responsible. Not long ago, you see, I was brought up on charges of obscurantisme, although the only “terroristic” aspects of it were self- directed—“Vous avez mal compris; vous êtes idiot.”1 But I’ve been rehabilitated, or perhaps, like Aphrodite in Iliad 5 (if you buy my reading), habilitated for the first time, to the joys of clearer prose. My committee is responsible for this, especially my chair Richard Janko and he who first intervened, Benjamin Fortson. I thank them. If something in here should appear refined, again this is likely owing to the good taste of my committee. And if something should appear peculiarly sensitive, empathic even, then it was the humanity of my committee that enabled, or at least amplified, this, too.