African American Settlements Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lake Plan Malcolm and Ardoch Lakes Background Document

THE LAKE PLAN MALCOLM AND ARDOCH LAKES BACKGROUND DOCUMENT i DISCLAIMER The information contained in this document is for information purposes only. It has been collected from sources we believe to be reliable, but completeness and accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The Malcolm Ardoch Lake Landowners’ Association (MALLA) and its members are not liable for any errors or omissions in the data and for any loss or damage suffered based upon the contents herein. Maps are provided only for general indications of position and are not designed for navigational purposes. Boaters and snowmobilers/all-terrain vehicles must take due care at all times on the lakes; users of the lakes are responsible for their own safety and well-being by making themselves aware of any hazards that may exist at any given time. BACKGROUND Preliminary work for the Lake Plan began in 2012 when the Malcolm Ardoch Lakes Association executive were asked for information related to the water quality of the two lakes. Some information was available through the Ministry of the Environment Lakes Partner Program due to the efforts of Ron Higgins for Malcolm and Ruth Cooper for Ardoch Lake who conducted water sampling to provide Secchi data. A second source was the five-year sampling rotation conducted by Mississippi Valley Conservation Authority. The implications of water quality and water levels initiated discussions about the need for consistent monitoring on the lakes. A Committee was formed under the leadership of Ron Higgins and topics beyond water quality were identified. A land development proposal for Ardoch Lake became an urgent matter and the Lake Plan was delayed. -

Historic, Architectural, Archaeological and Cultural Resources

Historic, Architectural, Environmental Impact Archaeological and Cultural Statement Resources (Section 106) Identify cultural resources within the Detailed Study Area Consult, as necessary, with the State Historic Preservation Officer and Tribal Historic Preservation Officer Since1949 P:\CMH\GIS_EIS_P150\GRAPHICS\7-11-06workshop\historic text.cdr Date: 6/11/06 SOMERSET GENERAL STUDY AREA NORTH EAST AUDUBON Columbus CREEKSIDE e Jefferson AUDUBON Mary Miller Patton House u !( GLEN ECHO n Gahanna e SHULL v 270 Township GLEN ECHO GLEN ECHO Mifflin A G ran PRIDE PARK ville Street y ¦¨§ MEMORIAL LINDEN d Township Glen Echo Historic District a s d s H .! a avens Corners a Ro o ad Ch C err y Road R JOAN s d e oa m Hus MOCK R FRIENDSHIP d on Street n a a w J to o CITY GATE s R GAHANNA WOODS hn Jo Her n mitage Ro o ad t l Mock R Muski i oad ngum m a e Road H u 670 n Ne RATHBURN WOODS e w burgh Drive Deniso v § n Ave y GAHANNA WOOD NATURE RESERVE ¨ n r ¦ u e bu A r te d l r d a l W eva a l e ou o n B t R n r GALLOWAY PRESERVE e k IUKA r o roo b b B Elizabeth J. & Louis C. Wallick r e d r av a a !( e Indianola Junior High School B ive FIVE ACRE WOODS PARKLAND IUKA OHIO HISTORICAL CENTER r o !( H D TAYLOR ROAD RESERVE e R d ! r . 71 u e a r Ar a gyle 1 Drive t u n o e B BRITTANY HILLS 0 e n e M n R e ¦¨§ L e v o r OHIO STATE FAIRGROUND r o r r v t A Vendo is me Dr g A ive e o .! S e n a z d MALONEY c l Ta ylor Ro h a W n e R d y R t o g a i l o 8 S a J e H AMVET VILLAGE 2 d v e Holt A l Seventeen venue C th Avenue I nternationa Pet l Gateway Cemetery e u WINDSOR n e d v a 1 o Y A d 0 PIZZURO R d a R n n BRENTNELL o o T a Airport i Y l R t Golf El AMERICAN ADDITION d a eventh Aven y t ue r o Course S u o r N T L b o W n 8 l New Indianola Historic District y u 2 d Thir raft Roa a ! S teenth Ave Clayc T CRAWFORD FARMS . -

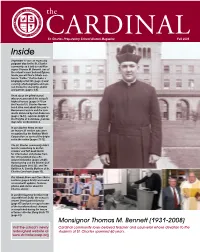

Fall 2008 Inside

the CARDINALSt. Charles Preparatory School Alumni Magazine Fall 2008 Inside September 11 was an especially poignant day for the St. Charles community as it laid to rest Mon- signor Thomas M. Bennett, one of the school’s most beloved figures. Inside you will find a tribute sec- tion to “Father” that includes a biography of his life (page 3) and a variety of photographs and spe- cial memories shared by alumni and parents (pages 4-8). Read about the gifted alumni who were presented the school’s highest honors (pages 9-11) on the Feast of St. Charles Novem- ber 4. Also read about this year’s Borromean Lecture and the com- ments delivered by Carl Anderson (pages 12-13), supreme knight of the Knights of Columbus, just two days later on November 6. In our Student News section we feature 31 seniors who were recognized by the National Merit Corporation as some of the bright- est in the nation (pages 11-12) The St. Charles community didn’t lack for something to do this summer and fall! Look inside for information and photos from the ’08 Combined Class Re- union Celebration (pages 24-25); Homecoming and the Alumni Golf Outing;(pages 28 & 33); and The Kathleen A. Cavello Mothers of St. Charles Luncheon (page 33). Our Alumni News and Class Notes sections (pages 34-45) are loaded as usual with updates, features, photos and stories about St. Charles alumni. In our Development Section read about Michael Duffy, the school’s newest Development Director (page 47) and get a recap of some of the transformational changes accomplished during the tenure of former director, Doug Stein ’78 (page 51). -

A History of Sport in British Columbia to 1885: Chronicle of Significant Developments and Events

A HISTORY OF SPORT IN BRITISH COLUMBIA TO 1885: CHRONICLE OF SIGNIFICANT DEVELOPMENTS AND EVENTS by DEREK ANTHONY SWAIN B.A., University of British Columbia, 1970 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES School of Physical Education and Recreation We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1977 (c) Derek Anthony Swain, 1977 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Depa rtment The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 ii ABSTRACT This paper traces the development of early sporting activities in the province of British Columbia. Contemporary newspapers were scanned to obtain a chronicle of the signi• ficant sporting developments and events during the period between the first Fraser River gold rush of 18 58 and the completion of the transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway in 188 5. During this period, it is apparent that certain sports facilitated a rapid expansion of activities when the railway brought thousands of new settlers to the province in the closing years of the century. -

Ohio PBIS Recognition Awards 2020

Ohio PBIS Recognition Awards 2020 SST Building District Level District Region Received Award Winners 1 Bryan Elementary Bryan City Bronze 1 Horizon Science Academy- Springfield Silver 1 Horizon Science Academy- Toledo Bronze 1 Fairfield Elementary Maumee City Schools Bronze 1 Fort Meigs Elementary Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Frank Elementary Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Hull Prairie Intermediate Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Perrysburg Junior High School Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Perrysburg High School Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Toth Elementary Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Woodland Elementary Perrysburg Exempted Village Bronze 1 Crissey Elementary Springfield Local Schools Bronze 1 Dorr Elementary Springfield Local Schools Silver 1 Old Orchard Elementary Toledo City Schools Bronze 1 Robinson Achievement Toledo City Schools Silver 2 Vincent Elementary School Clearview Local School District Bronze 2 Lorain County Early Learning Center Educational Service Center of Lorain Bronze County 2 Prospect Elementary School Elyria City Schools Bronze 2 Keystone Elementary School Keystone City Schools Silver 2 Keystone High School Keystone City Schools Silver 2 Keystone Middle School Keystone City Schools Silver 2 Midview East Intermediate School Midview Local School District Bronze 2 Midview High School Midview Local School District Bronze 2 Midview Middle School Midview Local School District Bronze 2 Midview North Elementary School Midview Local School District Bronze 2 Midview West Elementary -

Smart Columbus Demonstration Site Map and Installation Schedule

Demonstration Site Map and Installation Schedule for the Smart Columbus Demonstration Program FINAL REPORT | January 24, 2020 Smart Columbus Produced by City of Columbus Notice This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. The U.S. Government is not endorsing any manufacturers, products, or services cited herein and any trade name that may appear in the work has been included only because it is essential to the contents of the work. Acknowledgment of Support This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Transportation under Agreement No. DTFH6116H00013. Disclaimer Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the Author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Transportation. Acknowledgments The Smart Columbus Program would like to thank project leads for each of the Smart Columbus projects for their assistance in drafting and reviewing this Demonstration Site Map and Installation Schedule. Demonstration Site Map and Installation Schedule – Final Report | Smart Columbus Program | i Abstract The City of Columbus, Ohio, won the United States Department of Transportation Smart City Challenge, receiving a pledge of $40 million to develop innovative transportation solutions. For its Smart Columbus program, the City will use advanced technologies in the service of all ages and economic groups while bridging the digital divide. The program will integrate Intelligent Transportation Systems and connected and autonomous vehicle technologies into other operational areas. -

1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconnaissance Survey

1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconnaissance Survey Final November 2005 National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 Summary Statement 1 Bac.ground and Purpose 1 HISTORIC CONTEXT 5 National Persp4l<live 5 1'k"Y v. f~u,on' World War I: 1896-1917 5 World W~r I and Postw~r ( r.: 1!1t7' EarIV 1920,; 8 Tulsa RaCR Riot 14 IIa<kground 14 TI\oe R~~ Riot 18 AIt. rmath 29 Socilot Political, lind Economic Impa<tsJRamlt;catlon, 32 INVENTORY 39 Survey Arf!a 39 Historic Greenwood Area 39 Anla Oubi" of HiOlorK G_nwood 40 The Tulsa Race Riot Maps 43 Slirvey Area Historic Resources 43 HI STORIC GREENWOOD AREA RESOURCeS 7J EVALUATION Of NATIONAL SIGNIFICANCE 91 Criteria for National Significance 91 Nalional Signifiunce EV;1lu;1tio.n 92 NMiol\ill Sionlflcao<e An.aIYS;s 92 Inl~ri ly E~alualion AnalY'is 95 {"",Iu,ion 98 Potenl l~1 M~na~menl Strategies for Resource Prote<tion 99 PREPARERS AND CONSULTANTS 103 BIBUOGRAPHY 105 APPENDIX A, Inventory of Elltant Cultural Resoun:es Associated with 1921 Tulsa Race Riot That Are Located Outside of Historic Greenwood Area 109 Maps 49 The African American S«tion. 1921 51 TI\oe Seed. of c..taotrophe 53 T.... Riot Erupt! SS ~I,.,t Blood 57 NiOhl Fiohlino 59 rM Inva.ion 01 iliad. TIll ... 61 TM fighl for Standp''''' Hill 63 W.II of fire 65 Arri~.. , of the Statl! Troop< 6 7 Fil'lal FiOlrtino ~nd M~,,;~I I.IIw 69 jii INTRODUCTION Summary Statement n~sed in its history. -

Mack Studies

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 381 472 SO 024 893 AUTHOR Botsch, Carol Sears; And Others TITLE African-Americans and the Palmetto State. INSTITUTION South Carolina State Dept. of Education, Columbia. PUB DATE 94 NOTE 246p. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Black Culture; *Black History; Blacks; *Mack Studies; Cultural Context; Ethnic Studies; Grade 8; Junior High Schools; Local History; Resource Materials; Social Environment' *Social History; Social Studies; State Curriculum Guides; State Government; *State History IDENTIFIERS *African Americans; South Carolina ABSTRACT This book is part of a series of materials and aids for instruction in black history produced by the State Department of Education in compliance with the Education Improvement Act of 1984. It is designed for use by eighth grade teachers of South Carolina history as a supplement to aid in the instruction of cultural, political, and economic contributions of African-Americans to South Carolina History. Teachers and students studying the history of the state are provided information about a part of the citizenry that has been excluded historically. The book can also be used as a resource for Social Studies, English and Elementary Education. The volume's contents include:(1) "Passage";(2) "The Creation of Early South Carolina"; (3) "Resistance to Enslavement";(4) "Free African-Americans in Early South Carolina";(5) "Early African-American Arts";(6) "The Civil War";(7) "Reconstruction"; (8) "Life After Reconstruction";(9) "Religion"; (10) "Literature"; (11) "Music, Dance and the Performing Arts";(12) "Visual Arts and Crafts";(13) "Military Service";(14) "Civil Rights"; (15) "African-Americans and South Carolina Today"; and (16) "Conclusion: What is South Carolina?" Appendices contain lists of African-American state senators and congressmen. -

The Ohio National Guard Before the Militia Act of 1903

THE OHIO NATIONAL GUARD BEFORE THE MILITIA ACT OF 1903 A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Cyrus Moore August, 2015 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Thesis written by Cyrus Moore B.S., Ohio University, 2011 M.A., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by Kevin J. Adams, Professor, Ph.D., Department of History Master’s Advisor Kenneth J. Bindas, Professor, Ph.D, Chair, Department of History James L Blank, Ph.D., Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter I. Republican Roots………………………………………………………19 II. A Vulnerable State……………………………………………………..35 III. Riots and Strikes………………………………………………………..64 IV. From Mobilization to Disillusionment………………………………….97 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………….125 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………..136 Introduction The Ohio Militia and National Guard before 1903 The second half of the nineteenth century witnessed a profound change in the militia in the United States. Driven by the rivalry between modern warfare and militia tradition, the role as well as the ideology of the militia institution fitfully progressed beyond its seventeenth century origins. Ohio’s militia, the third largest in the country at the time, strove to modernize while preserving its relevance. Like many states in the early republic, Ohio’s militia started out as a sporadic group of reluctant citizens with little military competency. The War of the Rebellion exposed the serious flaws in the militia system, but also demonstrated why armed citizen-soldiers were necessary to the defense of the state. After the war ended, the militia struggled, but developed into a capable military organization through state-imposed reform. -

Arts and Culture in Columbus Creating Competitive Advantage and Community Benefit Columbus Cultural Leadership Consortium Member Organizations

A COMMUNITY DISCUSSION PAPER presented by: COLUMBUS CULTURAL LEADERSHIP CONSORTIUM SEPTEMBER 21, 2006 Arts and Culture in Columbus Creating Competitive Advantage and Community Benefit Columbus Cultural Leadership Consortium Member Organizations BalletMet Center of Science and Industry (COSI) Columbus Association for the Performing Arts (CAPA) Columbus Children’s Theatre Columbus Museum of Art Columbus Symphony Orchestra Contemporary American Theatre Company (CATCO) Franklin Park Conservatory Greater Columbus Arts Council (GCAC) Jazz Arts Group The King Arts Complex Opera Columbus Phoenix Theatre ProMusica Chamber Orchestra Thurber House Wexner Center for the Arts COLUMBUS CULTURAL LEADERSHIP CONSORTIUM Table of Contents Executive Summary . 2 Introduction . 4 Purpose . 4 State of the Arts . 5 Quality Proposition . 5 Finances at a Glance . 9 Partnerships as Leverage . 11 Public Value and Community Advantage . 13 Education and Outreach . 14 Economic Development . 17 Community Building . 21 Marketing . 23 Imagining Enhanced Community Benefit . 24 Vision and Desired Outcomes . 24 Strategic Timeline for Reaching Our Vision . 28 “The Crossroads” Conclusion . 28 Table 1: CCLC Member Organization Key Products and Services . 29 Table 2: CCLC Member Organization Summary Information . 31 Table 3: CCLC Member Organization Offerings at a Glance . 34 Endnotes . 35 Bibliography . 37 Issued September 21, 2006 1 COLUMBUS CULTURAL LEADERSHIP CONSORTIUM Executive Summary Desired Outcomes Comprised of 16 organizations, the Columbus 1. Culture and arts will form a significant Cultural Leadership Consortium (CCLC, or “the differentiator for our city and contribute to its consortium”) was created early in 2006 to bring overall economic development. organization and voice to the city’s major cultural and artistic “anchor” institutions, with a focus on It is sobering to see the results of a 2005 study policy and strategy in both the short term and over conducted by the Columbus Chamber, indicating the long haul. -

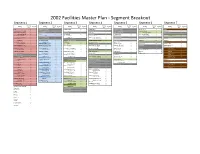

2002 Facilities Master Plan - Segment Breakout Segment 1 Segment 2 Segment 3 Segment 4 Segment 5 Segment 6 Segment 7

2002 Facilities Master Plan - Segment Breakout Segment 1 Segment 2 Segment 3 Segment 4 Segment 5 Segment 6 Segment 7 Planning Planning Planning Planning Planning Planning Planning Building Segment Building Segment Building Segment Building Segment Building Segment Building Segment Building Segment Area Area Area Area Area Area Area FHCC 1 1 Crestview MS (New) 1 2 Colerain (New) 1 3 Cranbrook ES 1 4 Everett MS (New) 1 5 Centennial HS 1 6 NWCC 1 7 New Fort Hayes MS (AIMS) 1 1 Crestview MS 1 2 Colerain 1 3 North Education Center 1 4 Everett MS 1 5 Clinton ES (New) 1 6 Avalon ES 2 7 Weinland Park ES (New) 1 1 Indianola MS 1 2 Medary ES 1 3 Salem ES 1 4 Fifth Alternative ES 1 5 Clinton ES (1922 Main Bldg)1 6 Brentnell ES 2 7 Weinland Park ES 1 1 FHHS 1 2 Winterset ES 1 3 Clinton MS 2 4 Ridgeview MS 1 5 Dominion MS (New) 1 6 East Linden ES (New) 2 1 A.G. Bell 2 2 Alpine ES (New) 2 3 Columbus Alt HS 2 4 Whetstone HS 1 5 Dominion MS 1 6 Ecole Kenwood Alt ES 1 7 East Linden ES 2 1 Gladstone ES (New) 2 2 Alpine ES 2 3 Duxberry Park Alt ES (New) 2 4 Brookhaven HS 2 5 Second Avenue ES 1 6 Hudson ES 2 7 Linden ES (New) 2 1 Gladstone ES 2 2 Arlington Park ES (New) 2 3 Duxberry Park Alt ES 2 4 Cassady Alt ES 2 5 Beechcroft HS 2 6 Innis ES 2 7 Linden ES 2 1 Huy Road ES (New) 2 2 Arlington Park ES 2 3 Gables ES (Ecole Kenwood) 1 4 Linmoor MS 2 5 Liberty ES 3 6 Mifflin HS 2 7 South Mifflin ES (New) 2 1 Huy Road ES 2 2 CSIA (New) 2 3 Indian Springs ES 1 3 Medina MS 2 5 Beery MS 4 6 NECC 2 7 South Mifflin ES 2 1 Indianola Alt ES 1 2 CSIA 2 3 McGuffey ES -

Ohio's 3Rd District (Joyce Beatty - D) Through 2018 LIHTC Properties in Ohio's 3Rd District Through 2018

LIHTC Properties in Ohio's 3rd District (Joyce Beatty - D) Through 2018 LIHTC Properties in Ohio's 3rd District Through 2018 Annual Low Rent or HUD Multi-Family Nonprofit Allocation Total Tax-Exempt Project Name Address City State Zip Code Allocated Year PIS Construction Type Income Income Credit % Financing/ Sponsor Year Units Bond Amount Units Ceiling Rental Assistance Both 30% 1951 PARSONS REBUILDING LIVES I COLUMBUS OH 43207 Yes 2000 $130,415 2000 Acquisition and Rehab 25 25 60% AMGI and 70% No AVE present value 3401 QUINLAN CANAL Not STRATFORD EAST APTS OH 43110 Yes 1998 $172,562 2000 New Construction 82 41 BLVD WINCHESTER Indicated 4855 PINTAIL CANAL 30 % present MEADOWS OH 43110 Yes 2001 $285,321 2000 New Construction 95 95 60% AMGI Yes CREEK DR WINCHESTER value WHITEHALL SENIOR 851 COUNTRY 70 % present WHITEHALL OH 43213 Yes 2000 $157,144 2000 New Construction 41 28 60% AMGI No HOUSING CLUB RD value 6225 TIGER 30 % present GOLF POINTE APTS GALLOWAY OH 43119 No 2002 $591,341 2001 Acquisition and Rehab 228 228 Yes WOODS WAY value GREATER LINDEN 533 E STARR 70 % present COLUMBUS OH 43201 Yes 2001 $448,791 2001 New Construction 39 39 50% AMGI No HOMES AVE value 423 HILLTOP SENIOR 70 % present OVERSTREET COLUMBUS OH 43228 Yes 2001 $404,834 2001 New Construction 100 80 60% AMGI No VILLAGE value WAY Both 30% 684 BRIXHAM KINGSFORD HOMES COLUMBUS OH 43204 Yes 2002 $292,856 2001 New Construction 33 33 60% AMGI and 70% RD present value 30 % present REGENCY ARMS APTS 2870 PARLIN DR GROVE CITY OH 43123 No 2002 $227,691 2001 Acquisition and