Guidelines for Preparation of Master's Thesis in Art History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE EVENING Jflomiiti Ttreatatkm Kitiktcm«4

654 Iti ttreatatkm kit IKTCM«4 Fov THE EVENING JflOMI Fold it Tkrae T—ru Scbahofer Frederick, (F. Schahofer & Co.), h 5 Sixth, Hobkn Schabofer F. & Co., (Frederick Schahofer db Charles Bracht) liquors, 5 Sixth, Hoboken Schakel Henry, liquors, Second c Jackson, Hoboken Schalk Philip, laborer, It Ma<lison n First, Hoboken Schalkhausser Angonite, wid John, h 210 Second • Schanck James, h 50 Mercer Schanck John W., (Schanck &Hough\ h 160 Grand Schanck Levi P., bookkeeper, h 163 Meadow, Hoboken SCHANCK & HOUGH, {John W. Schanck & Washington 1. Hough), coal, 1 Montgomery & ft Hudson & Essex Schankweiler George, grocer, 193 Montgomery Schapcote Henry, coverlet maker, 146 Garden, Hoboken Schappler Christopher, baker, h r 250 R It av Scharfenberg Werner, cntter, h Beacon av n Central av Schasberger August, lager, 37 Fifth, Hoboken Schasberger Otto, [Drinhmann cfe Schasberger)^ h Fifth n Bloomfieid, fitoboken »-\ *•-" •"•'••H *r Schaser Jacob, h Newark av ?i Tonnele av Schaser John J., confectioner, h 107 Newark av Schauffale Henry, bookkeeper, h 238 Washington, Hoboken Schaufler Edward, shoemaker, 110 Meadow, Hoboken Scheel Peter, machinist, h 351 Second ^Scheerer Paul, driver, h 356 Second Scheibe Frederick, fnrnitnre, Central av n Zabriskie Scheibe Gustave F., drygoods, Ocean av n Kearney av Scheid Charles, segars, h Bridgman av n Summit av Scheid Franklitt H., segare, Monticello av c Harrison av Scheinheir Anton, printer, h 181 Washington, Hoboken Schell Charles, laborer, h r 225 R R av Schell Sylvester, h ZH Wayne • Schellensehlaeger Peter, watchman, h 182 Meadow, Hobk'n Schellenschlaeger William, barber, Zabriskie *n Nelson av Schellworth Albert H., carpenter, h 46 Coles Schemmer William, grocer, Palisade av c Cedar Schenck Augustus, clerk, h 88 Steeond, Hoboken Schenck Frederick, bartender, h 191 Newark av GERMANIAFIRE INSURANCE NEWARK, IV. -

Porcellian Club Centennial, 1791-1891

nia LIBRARY UNIVERSITY W CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO NEW CLUB HOUSE PORCELLIAN CLUB CENTENNIAL 17911891 CAMBRIDGE printed at ttjr itttirnsiac press 1891 PREFATORY THE new building which, at the meeting held in Febru- ary, 1890, it was decided to erect has been completed, and is now occupied by the Club. During the period of con- struction, temporary quarters were secured at 414 Harvard Street. The new building stands upon the site of the old building which the Club had occupied since the year 1833. In order to celebrate in an appropriate manner the comple- tion of the work and the Centennial Anniversary of the Founding of the Porcellian Club, a committee, consisting of the Building Committee and the officers of the Club, was chosen. February 21, 1891, was selected as the date, and it was decided to have the Annual Meeting and certain Literary Exercises commemorative of the occasion precede the Dinner. The Committee has prepared this volume con- taining the Literary Exercises, a brief account of the Din- ner, and a catalogue of the members of the Club to date. A full account of the Annual Meeting and the Dinner may be found in the Club records. The thanks of the Committee and of the Club are due to Brothers Honorary Sargent, Isham, and Chapman for their contribution towards the success of the Exercises Literary ; also to Brother Honorary Hazeltine for his interest in pre- PREFATORY paring the plates for the memorial programme; also to Brother Honorary Painter for revising the Club Catalogue. GEO. B. SHATTUCK, '63, F. R. APPLETON, '75, R. -

QUES in ARCH HIST I Jump to Today Questions in Architectural History 1

[email protected] - QUES IN ARCH HIST I Jump to Today Questions in Architectural History 1 Faculty: Zeynep Çelik Alexander, Reinhold Martin, Mabel O. Wilson Teaching Fellows: Oskar Arnorsson, Benedict Clouette, Eva Schreiner Thurs 11am-1pm Fall 2016 This two-semester introductory course is organized around selected questions and problems that have, over the course of the past two centuries, helped to define architecture’s modernity. The course treats the history of architectural modernity as a contested, geographically and culturally uncertain category, for which periodization is both necessary and contingent. The fall semester begins with the apotheosis of the European Enlightenment and the early phases of the industrial revolution in the late eighteenth century. From there, it proceeds in a rough chronology through the “long” nineteenth century. Developments in Europe and North America are situated in relation to worldwide processes including trade, imperialism, nationalism, and industrialization. Sequentially, the course considers specific questions and problems that form around differences that are also connections, antitheses that are also interdependencies, and conflicts that are also alliances. The resulting tensions animated architectural discourse and practice throughout the period, and continue to shape our present. Each week, objects, ideas, and events will move in and out of the European and North American frame, with a strong emphasis on relational thinking and contextualization. This includes a historical, relational understanding of architecture itself. Although the Western tradition had recognized diverse building practices as “architecture” for some time, an understanding of architecture as an academic discipline and as a profession, which still prevails today, was only institutionalized in the European nineteenth century. -

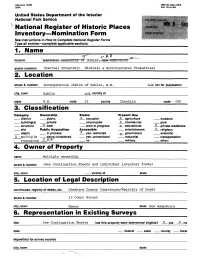

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service ' National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections______________ 1. Name H historic DUBLIN r-Offl and/or common (Partial Inventory; Historic & Architectural Properties) street & number Incorporation limits of Dublin, N.H. n/W not for publication city, town Dublin n/a vicinity of state N.H. code 33 county Cheshire code 005 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public , X occupied X agriculture museum building(s) private -_ unoccupied x commercial park structure x both work in progress X educational x private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment x religious object in process x yes: restricted X government scientific X multiple being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation resources X N/A" no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Multiple ownership street & number (-See Continuation Sheets and individual inventory forms) city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Cheshire County Courthouse/Registry of Deeds street & number 12 Court Street city, town Keene state New Hampshire 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title See Continuation Sheets has this property been determined eligible? _X_ yes _JL no date state county local depository for survey records city, town state 7. Description N/A: See Accompanying Documentation. Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered __ original site _ggj|ood £ __ ruins __ altered __ moved date _1_ fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance jf Introductory Note The ensuing descriptive statement includes a full exposition of the information requested in the Interim Guidelines, though not in the precise order in which. -

Tiffany Memorial Windows

Tiffany Memorial Windows: How They Unified a Region and a Nation through Women’s Associations from the North and the South at the Turn of the Twentieth Century Michelle Rene Powell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master’s of Arts in the History of Decorative Arts The Smithsonian Associates and Corcoran College of Art and Design 2012 ii ©2012 Michelle Rene Powell All Rights Reserved i Table of Contents List of Illustrations i Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Old Blandford Church, American Red Cross Building, and Windows 8 The Buildings 9 The Windows in Old Blandford Church 18 The Windows in the National American Red Cross Building 18 Comparing the Window Imagery 22 Chapter 2: History of Women’s Memorial Associations 30 Ladies’ Memorial Associations 30 United Daughters of the Confederacy 34 Woman’s Relief Corps 39 Fundraising 41 Chapter 3: Civil War Monuments and Memorials 45 Monuments and Memorials 45 Chapter 4: From the Late Twentieth Century to the Present 51 What the Windows Mean Today 51 Personal Reflections 53 Endnotes 55 Bibliography 62 Illustrations 67 ii List of Illustrations I.1: Tiffany Glass & Decorating Company, Reconstruction of 1893 Tiffany Chapel 67 Displayed at the Columbian Exposition I.2: Tiffany Glass & Decorating Company advertisement, 1898 68 I.3: Tiffany Glass & Decorating Company advertisement, 1895 69 I.4: Tiffany Glass & Decorating Company advertisement, 1899 70 I.5: Tiffany Studios, Materials in Glass and Stone, 1913 71 I.6: Tiffany Studios, Tributes to Honor, 1918 71 1.1: Old Blandford Church exterior 72 1.2: Old Blandford Church interior 72 1.3: Depictions of the marble buildings along 17th St. -

SUN BUILDING, 280 Broadway, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Camnission October 7, 1986; Designation List 186 LP-1439 SUN BUILDING, 280 Broadway, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1845-46, 1850-51, 1852-53, 1872, 1884; architects Joseph Trench & Co., Trench & Snook, [Frederick] Schmidt, Edward D. Harris Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 153, Lot 1 in part consisting of the land on which the described building is situated. On June 14, 1983, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Sun Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 14}. The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Two witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. The Camnission has received l etters and other expressions of support in favor of this designation, including a letter from the Camnissioner of the Department of General Services. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Sun Building, originally the A.T. Stewart Store, is one of the most influential buildings erected in New York City during the 19th century. Its appearance in 1846 (Fig.1} introduced a new architectural mode based on the palaces of the Italian Renaissance. Designed by the New York architects, Joseph Trench and John B. Snook, it was built by one of the century's greatest merchants, Alexander Turney Stewart. Within its marble walls, Stewart began the city's first department store, a type of commercial enterprise which was to have a great effect on the city's economic growth and which would change the way of merchandising in this country. -

Statue of Liberty National Monument and Ellis Island New Jersey and New York July 2018 Foundation Document

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Statue of Liberty National Monument and Ellis Island New Jersey and New York July 2018 Foundation Document NEW JERSEY HUDSON JERSEY CITY RIVER NEW YORK Ferry tickets MANHATTAN N Railroad Terminal ew J e r Liberty State Park s e Ferry tickets y Battery f Castle Clinton e Park Ellis r National r Island y Monument Statue of Liberty National y EAST RIVER rr Monument e f rk o Y ew Governors Island Liberty N National Monument Island North 0 0.5 Kilometer BROOKLYN 0 0.5 Mile ELLIS ISLAND IMMIGRATION MUSEUM Interior shown at right Ferry Building American Immigrant Museum Wall of Honor Entrance Ellis Island Fort Gibson 0 75 meters 0 250 feet Buildings shown in gray are closed to the public. Statue of Liberty National Monument and Ellis Island Contents Mission of the National Park Service 1 Introduction 2 Part 1: Core Components 3 Brief Description of the Park 3 Statue of Liberty National Monument 3 Ellis Island 5 Park Purpose 6 Park Significance 7 Fundamental Resources and Values 8 Other Important Resources and Values 10 Interpretive Themes 10 Part 2: Dynamic Components 11 Special Mandates and Administrative Commitments 11 Special Mandates 11 Administrative Commitments 11 Assessment of Planning and Data Needs 12 Analysis of Fundamental Resources and Values 13 Analysis of Other Important Resources and Values 28 Identification of Key Issues and Associated Planning and Data Needs 31 Planning and Data Needs 31 Part 3: Contributors 33 Statue of Liberty National Monument and -

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in the Corcoran Gallery of Art

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art VOLUME I THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C. A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art Volume 1 PAINTERS BORN BEFORE 1850 THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C Copyright © 1966 By The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20006 The Board of Trustees of The Corcoran Gallery of Art George E. Hamilton, Jr., President Robert V. Fleming Charles C. Glover, Jr. Corcoran Thorn, Jr. Katherine Morris Hall Frederick M. Bradley David E. Finley Gordon Gray David Lloyd Kreeger William Wilson Corcoran 69.1 A cknowledgments While the need for a catalogue of the collection has been apparent for some time, the preparation of this publication did not actually begin until June, 1965. Since that time a great many individuals and institutions have assisted in com- pleting the information contained herein. It is impossible to mention each indi- vidual and institution who has contributed to this project. But we take particular pleasure in recording our indebtedness to the staffs of the following institutions for their invaluable assistance: The Frick Art Reference Library, The District of Columbia Public Library, The Library of the National Gallery of Art, The Prints and Photographs Division, The Library of Congress. For assistance with particular research problems, and in compiling biographi- cal information on many of the artists included in this volume, special thanks are due to Mrs. Philip W. Amram, Miss Nancy Berman, Mrs. Christopher Bever, Mrs. Carter Burns, Professor Francis W. -

Annual Report 2000

2000 ANNUAL REPORT NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART 2000 ylMMwa/ Copyright © 2001 Board of Trustees, Cover: Rotunda of the West Building. Photograph Details illustrated at section openings: by Robert Shelley National Gallery of Art, Washington. p. 5: Attributed to Jacques Androet Ducerceau I, All rights reserved. The 'Palais Tutelle' near Bordeaux, unknown date, pen Title Page: Charles Sheeler, Classic Landscape, 1931, and brown ink with brown wash, Ailsa Mellon oil on canvas, 63.5 x 81.9 cm, Collection of Mr. and Bruce Fund, 1971.46.1 This publication was produced by the Mrs. Barney A. Ebsworth, 2000.39.2 p. 7: Thomas Cole, Temple of Juno, Argrigentum, 1842, Editors Office, National Gallery of Art Photographic credits: Works in the collection of the graphite and white chalk on gray paper, John Davis Editor-in-Chief, Judy Metro National Gallery of Art have been photographed by Hatch Collection, Avalon Fund, 1981.4.3 Production Manager, Chris Vogel the department of photography and digital imaging. p. 9: Giovanni Paolo Panini, Interior of Saint Peter's Managing Editor, Tarn Curry Bryfogle Other photographs are by Robert Shelley (pages 12, Rome, c. 1754, oil on canvas, Ailsa Mellon Bruce 18, 22-23, 26, 70, 86, and 96). Fund, 1968.13.2 Editorial Assistant, Mariah Shay p. 13: Thomas Malton, Milsom Street in Bath, 1784, pen and gray and black ink with gray wash and Designed by Susan Lehmann, watercolor over graphite, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Washington, DC 1992.96.1 Printed by Schneidereith and Sons, p. 17: Christoffel Jegher after Sir Peter Paul Rubens, Baltimore, Maryland The Garden of Love, c. -

New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Vol 51

3 '< .^' -- -V -^^ S* -o^X .0 o^ ^0' ^^v Digitized by the Internet Archive ^^^ «"'*'^ in 2008 with funding from </' \.*^' The Library of Congress u .4" ^=^-\ ^ ^.^•, ^.^ .^' http ://wwW. arcti i Ve.o rg/detai Is/n ewyorkg^neklo^51 1^ ^wy mm: .r^ -^.m^: /%, V .s:^'"^ '/ •• "5 , „ s .\ ' o , * cP-."V o 0* ^^ ^ , » .0' -^'^•^-^''%. ,^\^r^.- x-^-^:<*^'/% •'^^- ,<^ i'i c^ •*>. oV -r, '''7., s^ \'^ a\ o .^^- °^ * s ^ aV V*'-Tr:«^^o> "<^^ kv^'' '^.!'^-\ 0> '^. \ c.^-^^.. y^^. ^^ v-i*^ ^-^ ^"^% '/ N^'' % .^'^^ ...?^C- .^^' '^. o5- ' ' .'^'>/' ^ ' " ,^•^'"^ .^'"' . » « " J^ * •*. '"'''.SA'' "^-i ' '^A V*' O 0^ -^p^ ^^'?*i., ^.^:^' ^ ,.%^ ^. $5.00 per Annum. Current Numbers, JJJl.Jio VOL. LI. No. I. THE NEW YORK Genealogical and Biographical Record. DEVOTED TO THE INTERESTS OF AMERICAN GENEALOGY AND BIOGRAPHY. ISSUED QUARTERLY. ;S2 »<?, ^1^!^ January, 1920 PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK GENEALOGICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY 226 West 58TH Street, New York. The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record. Publication Committee : HOPPER STRIKER MOTT, Editor. JOHN R. TOTTEN, Financial Editor. JOHN EDWIN STILLWELL, M. D. TOBIAS A. WRIGHT. ROYDEN WOODWARD VOSBURGH. REV. S. WARD RIGHTER. CAPT. RICHARD HENRY GREENE. MRS. ROBERT D. BRISTOL. RICHARD SCHERMERHORN, JR. CHARLES J. WERNER JANUARY, 1920.—CONTENTS. PAGE Illustrations Portrait of .Andrew Carnegie . , Frontispiece Portrait of Hon. Capt. Ciiristopher Christopliers Facing 18 " Portrait of Saraii (Prout) Christophiers 20 " ."ivpry ."irms 84 " Portrait of Samuel Putnam ,^ very. Sr 86 " Portrait of Samuel Putnam Avery 90 " Portraitof Dr. Reuel Stewart 92 1. Andrew Carnegie. Contributed by John R. Totten i 2. Christophers Family. Contributed by John R. Totten. (Continued from Vol. L, p. 334) 8 3. PuRDY, GuiON, Beecher AND Thomas FAMILY NoTES. -

Changing Patterns of Urban Retailing

ChangingPatterns of Urban Retailing: The 1920s JamesH. Madison Departmentof History,Indiana University During the 1920s fundamental changes occurred in business institutions responsible for retail distribution. Most signif- icantly, the large urban department store began a period of rela- tive decline and new forms of retailing emerged as strong compet- itors for sales volume. This paper describes these developments and attempts to show their relationship to the changing structure of American cities and to the changing strategies and structures of retail business institutions. It attempts also to show that changes in urban retailing commonly associated with post-World War II were well underway by the 1920s. First appearing in the third quarter of the 19th century, the department store occupied by 1900 the preeminent position in urban retailing, the consequence in part of the transformation of the city in the late 19th century. Rapid urban population growth and the spread of mass transit lines created a large number of consumers in a concentrated market area. Located at the conver- gence of transit lines and at the focal point of the newly con- centrated central business district, department stores drew cus- tomers from the entire city and increasingly from the surrounding countryside -- as many as 40,000 a day through Philadelphia's leading department store [18; 48; and 45, p. 467]. The compact and centralized spatial structure of late 19th century cities was a primary factor enabling the department store to achieve unprecedentedly high sales volume. That high volume resulted also from the strategy of selling under one roof goods of great variety, especially those appealing to a rapidly growing middle-class urban population. -

General Background

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Earth and Mineral Sciences RESTRUCTURING DEPARTMENT STORE GEOGRAPHIES: THE LEGACIES OF EXPANSION AND CONSOLIDATION IN PHILADELPHIA’S JOHN WANAMAKER AND STRAWBRIDGE & CLOTHIER, 1860-1960 A Thesis in Geography by Wesley J Stroh © 2008 Wesley J Stroh Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science August 2008 The thesis of Wesley J. Stroh was reviewed and approved* by the following: Deryck W. Holdsworth Professor of Geography Thesis Adviser Roger M. Downs Professor of Geography Karl Zimmerer Professor of Geography Head of the Department of Geography *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ABSTRACT RESTRUCTURING DEPARTMENT STORE GEOGRAPHIES: THE LEGACIES OF EXPANSION AND CONSOLIDATION IN PHILADELPHIA’S JOHN WANAMAKER AND STRAWBRIDGE & CLOTHIER, 1860-1960 Consolidation in the retail sector continues to restructure the department store, and the legacies of earlier forms of the department store laid the foundation for this consolidation. Using John Wanamaker’s and Strawbridge & Clothier, antecedents of Macy’s stores in Philadelphia, I undertake a case study of the development, through expansion and consolidation, which led to a homogenized department store retail market in the Philadelphia region. I employ archival materials, biographies and histories, and annual reports to document and characterize the development and restructuring Philadelphia’s department stores during three distinct phases: early expansions, the first consolidations into national corporations, and expansion through branch stores and into suburban shopping malls. In closing, I characterize the processes and structural legacies which department stores inherited by the latter half of the 20th century, as these legacies are foundational to national-scale retail homogenization.