Clothes and the Man, by Alan Flusser

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entrepreneuring in Africa's Emerging Fashion Industry

Fashioning the Future Entrepreneuring in Africa’s Emerging Fashion Industry Langevang, Thilde Document Version Accepted author manuscript Published in: The European Journal of Development Research DOI: 10.1057/s41287-016-0066-z Publication date: 2017 License Unspecified Citation for published version (APA): Langevang, T. (2017). Fashioning the Future: Entrepreneuring in Africa’s Emerging Fashion Industry. The European Journal of Development Research, 29(4), 893-910. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-016-0066-z Link to publication in CBS Research Portal General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us ([email protected]) providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Fashioning the Future: Entrepreneuring in Africa’s Emerging Fashion Industry Thilde Langevang Journal article (Accepted version*) Please cite this article as: Langevang, T. (2017). Fashioning the Future: Entrepreneuring in Africa’s Emerging Fashion Industry. The European Journal of Development Research, 29(4), 893-910. DOI: 10.1057/s41287-016-0066-z This is a post-peer-review, pre-copyedit version of an article published in The European Journal of Development Research. The final authenticated version is available online at: DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-016-0066-z * This version of the article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the publisher’s final version AKA Version of Record. -

The Morgue File 2010

the morgue file 2010 DONE BY: ASSIL DIAB 1850 1900 1850 to 1900 was known as the Victorian Era. Early 1850 bodices had a Basque opening over a che- misette, the bodice continued to be very close fitting, the waist sharp and the shoulder less slanted, during the 1850s to 1866. During the 1850s the dresses were cut without a waist seam and during the 1860s the round waist was raised to some extent. The decade of the 1870s is one of the most intricate era of women’s fashion. The style of the early 1870s relied on the renewal of the polonaise, strained on the back, gath- ered and puffed up into an detailed arrangement at the rear, above a sustaining bustle, to somewhat broaden at the wrist. The underskirt, trimmed with pleated fragments, inserting ribbon bands. An abundance of puffs, borders, rib- bons, drapes, and an outlandish mixture of fabric and colors besieged the past proposal for minimalism and looseness. women’s daywear Victorian women received their first corset at the age of 3. A typical Victorian Silhouette consisted of a two piece dress with bodice & skirt, a high neckline, armholes cut under high arm, full sleeves, small waist (17 inch waist), full skirt with petticoats and crinoline, and a floor length skirt. 1894/1896 Walking Suit the essential “tailor suit” for the active and energetic Victorian woman, The jacket and bodice are one piece, but provide the look of two separate pieces. 1859 zouave jacket Zouave jacket is a collarless, waist length braid trimmed bolero style jacket with three quarter length sleeves. -

Character Costume Items to Be Provided by Families

Class Class Class Teacher Role/ Costume items to be provided by families & special instructions from Day Time Type Character teachers Monday 4:00 pm Tap & Creative Lisa Swedish Fish Ballet shoes. Light pink footed ballet tights. Black leotard. Dance (Age 3) Monday 4:15 pm Jazz I (age 7-8) Kelly Librarians Blue jeans you can dance in, black tap shoes, solid bright color crew socks (no logos, designs, or embellishments). Monday 4:25 pm Ballet V (Ages Kim Musical Notes Black class leotard. Bright, solid-colored footed tights, any color. Ballet shoes. 11-15) Monday 4:50 pm Tap & Creative Lisa Glow Worms Girls: Black leotard, no skirt. Pink footed ballet tights. Ballet shoes. Boys: bright, Dance (Age 4) solid-colored t-shirt. Black leggings/sweat pants. Ballet shoes. Monday 5:00 pm Tap I (Age 7-8) Kelly James Blue jeans you can dance in, black tap shoes, solid bright color crew socks (no logos, designs, or embellishments). Tuesday 4:00 pm Tap & Pre-Ballet Posy Glow Worms Pink footed ballet tights, any bright solid-colored leggings, any bright solid-colored (Age 4) leotard, pink ballet shoes. Tuesday 4:15 pm Ballet III (Ages Faith BFG's friend Any light blue knee length dress with black class leotard worn underneath. Pink 9-13) footed ballet tights. Pink ballet shoes. Dress example: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B018J4D8UM?psc=1&redirect=true&ref_=ox_s c_act_title_1&smid=ATVPDKIKX0DER Hair firmly secured in proper ballet bun at the crown of the head with headpiece (provided by Danceworks) secured above. Make-up that highlights the eyes, cheeks, and lips. -

Looking at the Past and Current Status of Kenya's Clothing and Textiles

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2018 Looking at the Past and Current Status of Kenya’s clothing and textiles Mercy V.W. Wanduara [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Art Practice Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons Wanduara, Mercy V.W., "Looking at the Past and Current Status of Kenya’s clothing and textiles" (2018). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 1118. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/1118 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings 2018 Presented at Vancouver, BC, Canada; September 19 – 23, 2018 https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/ Copyright © by the author(s). doi 10.32873/unl.dc.tsasp.0056 Looking at the Past and Current Status of Kenya’s clothing and textiles Mercy V. W. Wanduara [email protected] Abstract This paper analyzes and documents traditional textiles and clothing of the Kenyan people before and after independence in 1963. The paper is based on desk top research and face to face interviews from senior Kenyan citizens who are familiar with Kenyan traditions. An analysis of some of the available Kenya’s indigenous textile fiber plants is made and from which a textile craft basket is made. -

FIREMAN HAT, DIAPER COVER, BOOTS and SUSPENDERS PATTERN by Expertcraftss

FIREMAN HAT, DIAPER COVER, BOOTS AND SUSPENDERS PATTERN by ExpertCraftss http://www.etsy.com/shop/ExpertCraftss Email: [email protected] Thank you for purchasing this pattern! If you have any questions, please don't hesitate to contact as above. Good luck and have fun creating this fun set! Maria Pickard MATERIALS NEEDED: H hook, I hook and J hook, depending on the size you wish to make. Red, black and silver yarn. I use "I love this yarn" medium worsted weight. I have also used red heart yarn which actually allows the hat to be a bit more sturdy but is definitely not as soft on baby. Buttons: 2 large for front of diaper cover. 4 smaller buttons for inside diaper cover so that suspenders can be attached. Size of buttons is related to your stitching and what will best fit and hold the flaps and suspenders in place. I try to get the largest button that will fit through stitching for front, 1 inch. There are no specific button holes so test your buttons. I force my buttons through so I know they will not slip out when on baby. Tapestry needle. Difficulty: Intermediate. Stitches used: Ch, sc, hdc, dc, FPdc, sl st. HAT: For newborn use H hook. For 3-6 month, use I hook. For 6-9 month, use I hook and follow directions in bold below. For 9-12 month, use J hook. Magic circle. 1. Ch 2, 8 dc in ring. Slip st to 1st dc. 8 st. 2. Ch 2, dc in same st as sl st. -

Bulletin John Iriks

The Rotary Club of Kwinana District 9465 Western Australia Chartered: 22 April 1971 Team 2020-21 President Bulletin John Iriks No 10 07th Sept. 2020 Secretary Brian McCallum President John Rotary Club of Kwinana is in its 50th year 1971/2021 Treasurer Stephen Castelli Good meeting tonight, Guest speaker Russell Cox from the City of Kwinana talking on the Kwinana Loop trail, a 21km circuit around the perimeter of the city, pleasing that it takes in the Rotary Wildflower Reserve as part of the layout. Facts & Figures Trialling our PA set-up the last couple of weeks, it’s becoming evident that the use of lapel microphones will be the way to go, primarily for our President and Attendance this week guest speakers, hand held mic’s just don’t cut it for a guest speaker. Total Members 28 We are purchasing a second lapel mic, it’s a learning curve optimising the Apologies 6 equipment we have, huge difference in cost, $4.3k to so far $180 inc. 2nd lapel. Make -up 1 Attended 21 Looking for a suitable local venue for our 50 year celebration bash, older Hon . Member 1 LOA members will recall we held our 25th at Alcoa Social Club, our 30th at Casuarina Guests 1 Hall and our 40 th at the then brand new Kelly Pavilion on Thomas Oval. Visitors Partners Special congratulations to Genevieve and Damian 74.0% on their 20th wedding anniversary celebrated on the 9th September, I suppose I should also add that Gladys and I reach our 56th on the 12th Stay safe. -

Concession Contract Format

SAMPLE CONCESSION CONTRACT FOR Historic-Style Candy Store AT Columbia State Historic Park STATE OF CALIFORNIA – NATURAL RESOURCES AGENCY DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION PARTNERSHIPS OFFICE 1416 NINTH STREET, 14TH FLOOR SACRAMENTO, CA 95814 Historic-Style Candy Store Concession Contract Columbia State Historic Park Historic-Style Candy Store SAMPLE CONCESSION CONTRACT INDEX 1. DESCRIPTION OF PREMISES ............................................................................ 2 2. CONDITION OF PREMISES ................................................................................ 2 3. TERM ................................................................................................................... 2 4. RENT .................................................................................................................... 3 5. GROSS RECEIPTS .............................................................................................. 5 6. USE OF PREMISES ............................................................................................. 6 7. INTERPRETIVE SETTINGS AND COSTUME ..................................................... 7 8. RATES, CHARGES AND QUALITY OF GOODS AND SERVICES ..................... 8 10. ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES .................................................................................. 9 11. HOUSEKEEPING, MAINTENANCE, REPAIR AND REMOVAL........................... 9 12. RESOURCE CONSERVATION .......................................................................... 11 13. HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCES -

F7eb73228f1ff535d9120c7e0ffd0

PRODUCT FEATURES GENERAL TOOL BELT MATERIAL and FEATURES 5609 BALLISTIC POLYESTER Premium quality ballistic poly fabric is woven with elevated tenacity polyester thread in a 2x2 or 2x3 basket weave with yarn made of unusually high denier strength, typically from 840 denier to 1680 denier. Denier refers to the weight and thickness of the yarn, not TOOLS & SPECIALTY ITEMS TOOLS & SPECIALTY necessarily to the strength of the fabric. The 2x2 "ballistic weave" is extraordinarily strong and lightweight, and resists abrasion and tearing. Ballistic poly fabric is great for high-use and extreme work applications. Patented pouch handles Allow for simple belt adjustments and easy one-hand carrying, and convenient on-hook storage. Heavy-duty stitching and rivets Bar-tack stitching and rivets used to reduce additional wear and to reinforce stress points for added durability. MULTI-USE, EASY ACCESS POCKETS Large main pockets and small side and interior pockets, allow for the carrying of a wide variety of tools. GENERAL SOFT SIDE MATERIAL and FEATURES ECPL38 POLYESTER Quality polyester fabric is woven with thread that has been coated with a synthetic polymer in order to increase durability and fabric strength. Polyester is a versatile yarn and can easily be blended with other fibers to enhance specific properties that create materials with wear, and environmental resistance. Polyester fibers have high tenacity as well as low environmental absorption which makes it able to handle stressful usage and work environments. Reinforced WEB HANDLES Padded web carrying handles for comfort and convenience. Heavy-duty stitching Heavy-duty, bar-tack stitching used to reduce additional wear and to reinforce stress points for added durability. -

Safety Footwear Catalogue

SAFETY FOOTWEAR CATALOGUE SAFETY FOOTWEAR Safety footwear: Protection, comfort, well-being and Many years of experience in durability safety footwear Focus on well-being Across its footwear brands, Honeywell Industrial Safety has Being an expert in safety footwear means caring developed a culture of innovation and expertise, to offer footwear about the customer’s well-being, finding the with high added value that meets the requirements of a job, a balance between excellent protection and real comfort. Honeywell Industrial Safety offers a specific environment or a geographical region. wide range of comfortable footwear inspired by the latest fashion trends and technological Our products combine advanced technology, comfort and developments. ergonomics to satisfy the needs of all our customers. Technology & innovation The knowledge and understanding of our partners’ expectations Our footwear ranges benefit from the latest ensure that we develop quality footwear that is durable and reliable, results of Honeywell and Otter research and developement: non metallic toecaps, flexible to provide functional, comfortable and attractive protection. and light weight shoes, slip resistant outsoles, technical textiles, modular insole system, ESD etc. Rigour & quality The Honeywell development expertise Content is combined with rigour and quality. All manufacturing is managed by a certified ISO 04 European Standards and Sizes 9001 quality assurance system. From the design HONEYWELL: of the footwear to the aftersales service, all tests are carried out to meet the latest EN Standard 06 Cocoon compliance. 11 Temptation® City 13 Urban evolution 16 (i)XTREM evolution 21 Oil & Gas - Energy 23 Executive 26 Athletic 30 Bacou Original 36 Bacou Original Free New Generation 41 Bac’Run® PUN FOR TECHNICAL QUESTIONS AND ORDERS 43 Nit’Lite® ABOUT OTTER FOOTWEAR, PLEASE 46 White range CONTACT OTTER CUSTOMER SERVICE : 49 Stitched and cemented ranges OTTER SCHUTZ GMBH 51 Firemen range Xantener Straße 6. -

Blazer Magazine

Fall 2015 / Winter 2016 ISSUE 10 Fall 2015 / Winter 2016 • ISSUE 10 ISSUE 39 MAGAZINE ISSUE 10 • FALL 2015 / WINTER 2016 Welcome to blazer for men 5 22 the blazer staff 4 Leave it to Sweden Embark on a journey to Eton’s homeland 8 trend report Find out what fall and winter have in store for men’s fashion. 14 CONTENTS The BLAZER shoe guide Step into the season knowing everything you need to know about men’s footwear 20 there’s an app for that What you need to know about the latest app trends 8 68 did you know? The Fashion Edition 27 56 smart car Ten things you need to know about German car company Mercedes-Benz 64 das style! How to visit Berlin in Style 50 big in japan Japanese company, Echizenya, is dressing men around the world 26 MEN OF STYLE Getting personal with the Blazer Boys 30 published by The Vital Group editor Patrick Huffman 155 Richmond St. East art director Jen Snow Toronto ON M5A 1N9 head writer Lisa Hannam Style is art business 416 214 5555 x25 photographer David Wile Cold climate outfts to inspire mobile 416 882 2428 stylist Gregory Lalonde 37 www.thevitalgroup.ca CREDITS saluti, prost! What to order for drinks in Milan or Berlin 60 JEWELLERY blazer WELCOME Our style, our commitment Independently and locally owned, Blazer for Men has a full staff of highly trained sales associates and supportive personnel. Each is committed to customer service that goes beyond the expected, making a great impression for the frst time customer, and setting the store apart from WELCOME TO BLAZER FOR MEN the competition for its loyal clients. -

Stitch Setting Chart

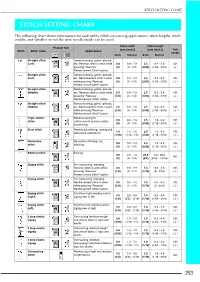

STITCH SETTING CHART STITCH SETTING CHART The following chart shows information for each utility stitch concerning applications, stitch lengths, stitch widths, and whether or not the twin needle mode can be used. Stitch width Stitch length Presser foot [mm (inch.)] [mm (inch.)] Twin Stitch Stitch name Applications needle Auto. Manual Auto. Manual Straight stitch General sewing, gather, pintuck, (Left) etc. Reverse stitch is sewn while 0.0 0.0 - 7.0 2.5 0.2 - 5.0 OK pressing “Reverse/ (0) (0 - 1/4) (3/32) (1/64 - 3/16) ( J ) Reinforcement Stitch” button. Straight stitch General sewing, gather, pintuck, (Left) etc. Reinforcement stitch is sewn 0.0 0.0 - 7.0 2.5 0.2 - 5.0 OK while pressing “Reverse/ (0) (0 - 1/4) (3/32) (1/64 - 3/16) ( J ) Reinforcement Stitch” button. Straight stitch General sewing, gather, pintuck, (Middle) etc. Reverse stitch is sewn while 3.5 0.0 - 7.0 2.5 0.2 - 5.0 OK pressing “Reverse/ (1/8) (0 - 1/4) (3/32) (1/64 - 3/16) ( J ) Reinforcement Stitch” button. Straight stitch General sewing, gather, pintuck, (Middle) etc. Reinforcement stitch is sewn 3.5 0.0 - 7.0 2.5 0.2 - 5.0 OK while pressing “Reverse/ (1/8) (0 - 1/4) (3/32) (1/64 - 3/16) ( J ) Reinforcement Stitch” button. Triple stretch General sewing for 0.0 0.0 - 7.0 2.5 1.5 - 4.0 OK stitch reinforcement and decorative (0) (0 - 1/4) (3/32) (1/16 - 3/16) ( J ) topstitching Stem stitch Reinforced stitching, sewing and 1.0 1.0 - 3.0 2.5 1.0 - 4.0 OK decorative applications (1/16) (1/16 - 1/8) (3/32) (1/16 - 3/16) ( J ) Decorative Decorative stitching, top 0.0 0.0 - 7.0 2.5 1.0 - 4.0 OK stitch stitching (0) (0 - 1/4) (3/32) (1/16 - 3/16) ( J ) Basting stitch Basting 0.0 0.0 - 7.0 20.0 5.0 - 30.0 NO (0) (0 - 1/4) (3/4) (3/16 - 1-3/16) Zigzag stitch For overcasting, mending. -

Travels of a Country Woman

Travels of a Country Woman By Lera Knox Travels of a Country Woman Travels of a Country Woman By Lera Knox Edited by Margaret Knox Morgan and Carol Knox Ball Newfound Press THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE LIBRARIES, KNOXVILLE iii Travels of a Country Woman © 2007 by Newfound Press, University of Tennessee Libraries All rights reserved. Newfound Press is a digital imprint of the University of Tennessee Libraries. Its publications are available for non-commercial and educational uses, such as research, teaching and private study. The author has licensed the work under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/>. For all other uses, contact: Newfound Press University of Tennessee Libraries 1015 Volunteer Boulevard Knoxville, TN 37996-1000 www.newfoundpress.utk.edu ISBN-13: 978-0-9797292-1-8 ISBN-10: 0-9797292-1-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2007934867 Knox, Lera, 1896- Travels of a country woman / by Lera Knox ; edited by Margaret Knox Morgan and Carol Knox Ball. xiv, 558 p. : ill ; 23 cm. 1. Knox, Lera, 1896- —Travel—Anecdotes. 2. Women journalists— Tennessee, Middle—Travel—Anecdotes. 3. Farmers’ spouses—Tennessee, Middle—Travel—Anecdotes. I. Morgan, Margaret Knox. II. Ball, Carol Knox. III. Title. PN4874 .K624 A25 2007 Book design by Martha Rudolph iv Dedicated to the Grandchildren Carol, Nancy, Susy, John Jr. v vi Contents Preface . ix A Note from the Newfound Press . xiii part I: The Chicago World’s Fair. 1 part II: Westward, Ho! . 89 part III: Country Woman Goes to Europe .