The Concept of Sovereignty in Vermont, 1750-1791 Christopher Demairo University of Vermont

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastern District* Nathaniel Niles 673 31.6% Daniel Buck 452 21.2% Jonathan Hunt 235 11.0% Stephen Jacob 233 10.9% Lewis R

1794 (ctd.) Eastern District* Nathaniel Niles 673 31.6% Daniel Buck 452 21.2% Jonathan Hunt 235 11.0% Stephen Jacob 233 10.9% Lewis R. Morris 177 8.3% Cornelius Lynde 100 4.7% Paul Brigham 71 3.3% Lot Hall 58 2.7% Elijah Robinson 28 1.3% Stephen R. Bradley 17 0.8% Samuel Cutler 16 0.8% Reuben Atwater 13 0.6% Daniel Farrand 12 0.6% Royal Tyler 11 0.5% Benjamin Green 7 0.3% Benjamin Henry 5 0.2% Oliver Gallup 3 0.1% James Whitelaw 3 0.1% Asa Burton 2 0.1% Benjamin Emmons 2 0.1% Isaac Green 2 0.1% Israel Morey 2 0.1% William Bigelow 1 0.0% James Bridgman 1 0.0% William Buckminster 1 0.0% Alexander Harvey 1 0.0% Samuel Knight 1 0.0% Joseph Lewis 1 0.0% Alden Spooner 1 0.0% Ebenezer Wheelock 1 0.0% Total votes cast 2,130 100.0% Eastern District (February 10, 1795, New Election) Daniel Buck [Federalist] 1,151 56.4% Nathaniel Niles [Democratic-Republican] 803 39.3% Jonathan Hunt [Federalist] 49 2.4% Stephen Jacob [Federalist] 39 1.9% Total votes cast 2,042 100.0% General Election Results: U. S. Representative (1791-1800), p. 3 of 6 1796 Western District* Matthew Lyon 1783 40.7% Israel Smith 967 22.1% Samuel Williams 322 7.3% Nathaniel Chipman 310 7.1% Isaac Tichenor 287 6.5% Gideon Olin 198 4.5% Enoch Woodbridge 188 4.3% Jonas Galusha 147 3.4% Daniel Chipman 86 2.0% Samuel Hitchcock 52 1.2% Samuel Safford 8 0.2% Jonathan Robinson 5 0.1% Noah Smith 4 0.1% Ebenezer Marvin 3 0.1% William C. -

Warren, Vermont

VERMONT BI-CENrENNIAI. COMMEMORATIVE. s a special tribute to the Vermont State Bi-Centennial Celebration, the A Waitsfield-Fayston Telephone Company has compiled a commemorative historical section for the 1991 telephone directory. Many hours of preparation went into this special edition and we hope that you will find it informative and entertaining. In 1979, we published a similar telephone book to honor the 75th year of business for the Waitsfield-Fayston Telephone Company. Through the years, folks have hung onto these books and requests for additional copies continued long after our supply was drpleted. Should you desire additional copies of the 1991 edition, we invite you to pick them up at our Business Office, Waitstield Cable, or our nunierous directory racks in business and store locations throughout the Valley. Special thanks go out to the many people who authored the histories in this section and loaned us their treasured pictures. As you read these histories, please be sure to notice the credits after each section. Without the help of these generous people, this project would not have been possible. In the course of reading this historical section, other events and recollections may come to mind. likewise,, you may be able to provide further detail on the people and locations pictured in this collection. The Waitsfield-Fayston Telephone Company, through our interest in the Valley’s heritage, wishes to continue compiling historical documentation. We encourage you to share your thoughts, ideas and comments with us. @ HAPPY20oTH BIRTHDAYVERMONT!! VERMONT BICENTENNIAL, 1 VERMONYBI-CENTENNLAL CUMMEMORATWE @ IN THE BEGINNING@ f the Valley towns - Fayston, Moretown, Waitsfield and Warren - 0Moretown was the only one not chartered during the period between 1777 and 1791 when Vermont was an Independent Republic. -

Bennington Battlefield 4Th Grade Activities

Battle of Bennington Fourth Grade Curriculum Guide Compiled by Katie Brownell 2014 Introduction: This curriculum guide is to serve as station plans for a fourth grade field trip to the Bennington Battlefield site. The students going on the field trip should be divided into small groups and then assigned to move between the stations described in this curriculum guide. A teacher or parent volunteer should be assigned to each station as well to ensure the stations are well conducted. Stations and Objectives: Each station should last approximately forty minutes, after which allow about five minutes to transition to the next station. The Story of the Battle Presentation: given previously to the field trip o Learn the historical context of the Battle of Bennington. o Understand why the battle was fought and who was involved. o Understand significance of the battle and conjecture how the battle may have affected the outcome of the Revolutionary War. Mapping Station: At the top of Hessian Hill using the relief map. o Analyze and discuss the transportation needs of people/armies during the 18th Century in this region based on information presented in the relief map at the top of Hessian Hill. o Create strategy for defense using relief map on top of Hessian Hill if you were Colonel Baum trying to defend it from a Colonial Attack. The Hessian Experience o Understand the point of view of the German soldiers participating in the battle. o Learn about some of the difficulties faced by the British. Historical Document Match Up: In field near upper parking lot* o Analyze documents/vignettes of historical people who played a role during the battle of Bennington. -

The Secret Places of the Heart by HG Wells</H1>

The Secret Places of the Heart by H. G. Wells The Secret Places of the Heart by H. G. Wells This etext was scanned By Dianne Bean with Omnipage Pro software donated by Caere. THE SECRET PLACES OF THE HEART BY H. G. WELLS 1922 CONTENTS Chapter 1. THE CONSULTATION 2. LADY HARDY page 1 / 331 3. THE DEPARTURE 4. AT MAIDENHEAD 5. IN THE LAND OF THE FORGOTTEN PEOPLES 6. THE ENCOUNTER AT STONEHENGE 7. COMPANIONSHIP 8. FULL MOON 9. THE LAST DAYS OF SIR RICHMOND HARDY THE SECRET PLACES OF THE HEART CHAPTER THE FIRST THE CONSULTATION Section 1 page 2 / 331 The maid was a young woman of great natural calmness; she was accustomed to let in visitors who had this air of being annoyed and finding one umbrella too numerous for them. It mattered nothing to her that the gentleman was asking for Dr. Martineau as if he was asking for something with an unpleasant taste. Almost imperceptibly she relieved him of his umbrella and juggled his hat and coat on to a massive mahogany stand. "What name, Sir?" she asked, holding open the door of the consulting room. "Hardy," said the gentleman, and then yielding it reluctantly with its distasteful three-year-old honour, "Sir Richmond Hardy." The door closed softly behind him and he found himself in undivided possession of the large indifferent apartment in which the nervous and mental troubles of the outer world eddied for a time on their way to the distinguished specialist. A bowl of daffodils, a handsome bookcase containing bound Victorian magazines and antiquated medical works, some paintings of Scotch scenery, three big armchairs, a buhl clock, and a bronze Dancing Faun, by their want of any collective idea enhanced rather than mitigated the promiscuous disregard of the room. -

This Week in Saratoga County History War on the Middleline

This Week in Saratoga County History War on the Middleline Submitted by Jim Richmond, October 15, 2020 Jim Richmond is a local independent historian, and the author of two books, “War on the Middleline” and “Milton, New York, A New Town in a New Nation” with co-author Kim McCartney. Jim is also a founding member of the Saratoga County History Roundtable and can be reached at [email protected] Historical Marker on Middleline Road, Town of Ballston Life as they knew it changed overnight. For years there had been fear, causing hardships day-by- day, but after this event their lives would never be the same. Much like our response to Pearl Harbor or September 11, October 16, 1780 was a day the people along Middleline Road in the Town of Ballston would never forget. The families along the road dividing the five-mile square in the Kayaderoseras patent had only recently arrived, most moving northwest less that 200 miles from their family homes in Connecticut. They were immediately met with the disruption of war. As Yankees, many of the them responded by supporting the patriot cause. Most of the men joined the 12th Regiment of the Albany County Militia. Their Lt. Colonel, James Gordon and their Captain, Tyrannius Collins lived among them. The pioneers settled north of their leaders along Middeline Road, clearing land, building their first cabins, barns and fences. The Revolution often took the men away from their families and farms. As militiamen, they were called to serve in the early years running down Loyalists, some of them former neighbors like William Fraser who had purchased 200 acres in Ballston in 1772. -

The Reception of Hobbes's Leviathan

This is a repository copy of The reception of Hobbes's Leviathan. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/71534/ Version: Published Version Book Section: Parkin, Jon (2007) The reception of Hobbes's Leviathan. In: Springborg, Patricia, (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Hobbes's Leviathan. The Cambridge Companions to Philosophy, Religion and Culture . Cambridge University Press , Cambridge , pp. 441-459. https://doi.org/10.1017/CCOL0521836670.020 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ jon parkin 19 The Reception of Hobbes’s Leviathan The traditional story about the reception of Leviathan was that it was a book that was rejected rather than read seriously.1 Leviathan’s perverse amalgamation of controversial doctrine, so the story goes, earned it universal condemnation. Hobbes was outed as an athe- ist and discredited almost as soon as the work appeared. Subsequent criticism was seen to be the idle pursuit of a discredited text, an exer- cise upon which young militant churchmen could cut their teeth, as William Warburton observed in the eighteenth century.2 We need to be aware, however, that this was a story that was largely the cre- ation of Hobbes’s intellectual opponents, writers with an interest in sidelining Leviathan from the mainstream of the history of ideas. -

Primary Sources Battle of Bennington Unit

Primary Sources Battle of Bennington Unit: Massachusetts Militia, Col. Simonds, Capt. Michael Holcomb James Holcomb Pension Application of James Holcomb R 5128 Holcomb was born 8 June 1764 and is thus 12 years old (!) when he first enlisted on 4 March 1777 in Sheffield, MA, for one year as a waiter in the Company commanded by his uncle Capt. Michael Holcomb. In April or May 1778, he enlisted as a fifer in Capt. Deming’s Massachusetts Militia Company. “That he attended his uncle in every alarm until some time in August when the Company were ordered to Bennington in Vermont […] arriving at the latter place on the 15th of the same month – that on the 16th his company joined the other Berkshire militia under the command of Col. Symonds – that on the 17th an engagement took place between a detachment of the British troops under the command of Col. Baum and Brechman, and the Americans under general Stark and Col. Warner, that he himself was not in the action, having with some others been left to take care of some baggage – that he thinks about seven Hundred prisoners were taken and that he believes the whole or a greater part of them were Germans having never found one of them able to converse in English. That he attended his uncle the Captain who was one of the guard appointed for that purpose in conducting the prisoners into the County of Berkshire, where they were billeted amongst the inhabitants”. From there he marches with his uncle to Stillwater. In May 1781, just before his 17th birthday, he enlisted for nine months in Capt. -

History of the Town of Shoreham, Vermont

NYPL RESEARCH LIBRARIES 3 3433 06813915 7 \^ v^t ^^ HISTORY OF THE VERMONT ™M the date of its CHARTEK, OCTOBER 8. ,. ^^^^' '^^ PKESENT TIME ' ™ ^Y REV. JOSIAH K GOODHUE, ^OG.THKK WITH . STATISTIC. A.. hiSTOKICA. ''''''' ^^' ™ co..Tr or ABB™"' BY SAMUEL SWIFT, ll. B. .;•"•,•. publish"eb'~^7^^^^,j^.. PRINTED BY MEAD & FULLER, MlDDLEBtJBT, Vt. 11678 PREFACE. Soon after the death of Gov. Silas H. Jenison, who had before been appointed to that service, the author of the followinof work was requested by the Committee of the Middlebury Historical So- ciety to write a history of the town of Shoreham. He soon becan to make mquiries and to collect materials to form into a history • but it was not until all those persons who first settled in this town were dead, with the exception of a single individual, that he en- tered upon the duties assigned him. The difficulties attending the prosecution of such an undertaking, under such circumstances, may easily be conceived, but these were aggravated by the absence of all records dating back beyond the year 1783. His only resource therefore, was to consult the only living man who had been here be- fore the Revolution, and a few of the older inhabitants who came soon after. It was a happy circumstance that Major Noah Callender had not then passed away, whose memory, though he was then more than eighty years old. remained unimpaired. The author held fre- quent conversations with him, and noted down whatever he deemed important for the prosecution of his work, and it is with pleasure he is able to state that on no important point has he found Major Callender's statements to be erroneous, after having been subjected to the severest tests. -

Locke and Rawls on Society and the State

The Journal of Value Inquiry 37: 217–231, 2003. JUSTIFICATION, LEGITIMACY, AND SOCIAL EMBEDDEDNESS 217 © 2003 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands. Justification, Legitimacy, and Social Embeddedness: Locke and Rawls on Society and the State SIMON CUSHING Department of Philosophy, University of Michigan-Flint, Flint, MI 48502-2186, USA; e-mail: [email protected] “The fundamental question of political philosophy,” wrote Robert Nozick memorably, “is whether there should be any state at all.”1 A. John Simmons concurs. For him, the task of “justifying the state” must take the following form: we should assume anarchism as a theoretical baseline and demonstrate that there can be at least one state type that is neither immoral nor inadvis- able.2 Justification is a separate task, however, from showing that any par- ticular state is legitimate for a particular individual, which means that the former has the right to rule over the latter. In “Justification and Legitimacy” Simmons contends that Locke’s political philosophy provides the model for the conceptual distinction between state justification and state legitimacy which has been lost in what he terms the Kantian turn of contemporary politi- cal philosophy. Modern followers of Kant, John Rawls chief among them, work with a conception of justification that is “doubly relativized” in com- parison with the Lockean notion.3 Instead of providing anarchists with objec- tive reasons for having states, Kantian justification is offered to those who already agree that some kind of -

“Jogging Along with and Without James Logan: Early Plant Science in Philadelphia”

1 Friday, 19 September 2014, 1:30–3:00 p.m.: Panel II: “Leaves” “Jogging Along With and Without James Logan: Early Plant Science in Philadelphia” Joel T. Fry, Bartram's Garden Presented at the ― James Logan and the Networks of Atlantic Culture and Politics, 1699-1751 conference Philadelphia, PA, 18-20 September 2014 Please do not cite, quote, or circulate without written permission from the author These days, John Bartram (1699-1777) and James Logan (1674-1751) are routinely recognized as significant figures in early American science, and particularly botanic science, even if exactly what they accomplished is not so well known. Logan has been described by Brooke Hindle as “undoubtedly the most distinguished scientist in the area” and “It was in botany that James Logan made his greatest contribution to science.” 1 Raymond Stearns echoed, “Logan’s greatest contribution to science was in botany.”2 John Bartram has been repeatedly crowned as the “greatest natural botanist in the world” by Linnaeus no less, since the early 19th century, although tracing the source for that quote and claim can prove difficult.3 Certainly Logan was a great thinker and scholar, along with his significant political and social career in early Pennsylvania. Was Logan a significant botanist—maybe not? John Bartram too may not have been “the greatest natural botanist in the world,” but he was very definitely a unique genius in his own right, and almost certainly by 1750 Bartram was the best informed scientist in the Anglo-American world on the plants of eastern North America. There was a short period of active scientific collaboration in botany between Bartram and Logan, which lasted at most through the years 1736 to 1738. -

Hclassifi Cation

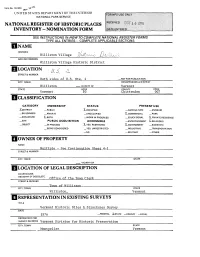

Form No. 10-300 ^ \Q~' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY ~ NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Williston Village AND/OR COMMON Williston Village Historic District LOCATION U.S. STREET & NUMBER Both sides of U.S. Rte. 2 _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Williston — VICINITY OF Vermont STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Vermont 50 Chit tend en 007 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE .X.DISTRICT _PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED X_COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE X_BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL K.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT X-RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED X-GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Multiple - See Continuation Sheet 4-1 STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.-ETC. Office of the Town Clerk STREET & NUMBER Town of Williston CITY. TOWN STATE Williston, Vermont REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Vermont Historic Sites § Structures Survey DATE 1976 —FEDERAL XSTATE _COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Vermont Division for Historic Preservation CITY. TOWN STATE Montpelier Vermont DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE XEXCELLENT _DETERIORATED X_UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE XGOOD _RUINS X_ALTERED X.MOVED DATE_____ XFAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Williston Village Historic District includes residential, commercial, municipal buildings and churches which line both sides of U.S. Route 2. The architecturally and historically significant buildings number approximately twenty-two. -

A Military History of America

Volume 1 French & Indian War — War of 1812 A Military History of America Created for free use in the public domain AmericanCreated Philatelic for free Society use in ©2012 the public • www.stamps.org domain American Philatelic Society ©2012 • www.stamps.org A Military History of America French & Indian War (1756–1763) y the time of the French and Indian War (known in Europe as the Seven Years War), England and France had been involved in a se- ries of ongoing armed conflicts, with scarcely a pause for breath, Bsince 1666. Some touched directly on colonial interests in North America, others did not, but in the end the conflict would become global in scope, with battles fought on land and sea in Europe, Asia, Africa, and North America. France had been exploiting the resources of the rich North American interior since Jacques Cartier first charted the St. Lawrence River in the 1530s–40s, exploring and establishing trading alliances with Native Americans south along the Mississippi River to New Orleans, north to Hudson Bay, and as far west as the Rocky Mountains. The English, in the meantime, had been establishing settled colonies along the eastern sea- board from the present-day Canadian Maritime Provinces to Georgia; Florida remained in the hands of Spain. In the 1740s the British Crown made a massive land grant in the Ohio river valley to certain Virginia colonists, including Governor Robert The earliest authenticated portrait of George Dinwiddie. The group formed the Ohio Company to exploit their new Washington shows him wearing his colonel's property.