Corn Stover and Wheat Straw Combustion in a 176-Kw Boiler Adapted for Round Bales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simulation of Corn Stover and Distillers Grains Gasification with Aspen Plus Ajay Kumar Oklahoma State University, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Chemical and Biomolecular Research Papers -- Yasar Demirel Publications Faculty Authors Series 2009 Simulation of Corn Stover and Distillers Grains Gasification with Aspen Plus Ajay Kumar Oklahoma State University, [email protected] Hossein Noureddini University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Yasar Demirel University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] David Jones University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Milford Hanna University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cbmedemirel Part of the Biochemical and Biomolecular Engineering Commons, Biomedical Engineering and Bioengineering Commons, and the Thermodynamics Commons Kumar, Ajay; Noureddini, Hossein; Demirel, Yasar; Jones, David; and Hanna, Milford, "Simulation of Corn Stover and Distillers Grains Gasification with Aspen Plus" (2009). Yasar Demirel Publications. 11. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cbmedemirel/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Chemical and Biomolecular Research Papers -- Faculty Authors Series at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yasar Demirel Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SIMULATION OF CORN STOVER AND DISTILLERS GRAINS GASIFICATION WITH ASPEN PLUS A. Kumar, H. Noureddini, Y. Demirel, D. D. Jones, M. A. Hanna ABSTRACT. A model was developed to simulate the performance of a lab‐scale gasifier and predict the flowrate and composition of product from given biomass composition and gasifier operating conditions using Aspen Plus software. -

Evaluating the Environmental Impact of Corn Stover Collection for Biofuels Production Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment O

Evaluating the Environmental Impact of Corn Stover Collection for Biofuels Production Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University. By Asmita Khanal, B.E. Environmental Science Graduate Program The Ohio State University 2018 Master’s Examination Committee: Dr. Ajay Shah, Advisor Dr. Harold Keener Dr. Frederick Michel Dr. Shauna Brummet Copyright by Asmita Khanal 2018 Abstract Corn stover is the most readily available lignocellulosic feedstock for cellulosic biofuel production in the Midwestern U.S. Biofuels produced from corn stover could offset the environmental impact of fossil fuel combustion. Corn stover harvest for biofuels production removes potentially recyclable nutrients and carbon, increases the vulnerability of the soil to soil erosion, and produces emissions during harvest and collection due to operation and manufacture of the machinery, thus challenging the sustainability of the process. The main objective of this research was to evaluate the environmental impact of corn stover removal for biofuel production by first determining physical and compositional attributes of the corn stover in terms of dry matter, structural carbohydrates, lignin and nutrients, and then quantifying the environmental impact of corn stover collection for biofuel production. In 2016 and 2017, stover fractions below and above ear-level, and cobs contributed 42-56%, 31-38% and 13-18% to the total non-grain aboveground dry matter, respectively. Based on this dry matter contribution of the different fractions, three different corn stover removal scenarios were established: 1) removal of cobs, 2) removal of stover above ear level excluding cobs, and 3) removal of stover above half way between ground and ear level excluding cobs, to analyze the environmental impact in terms of greenhouse gases emissions in comparison to the base case scenario, i.e., no stover removal. -

Optimization of Biofuel Production from Corn Stover Under Supply Uncertainty in Ontario

Biofuel Research Journal 16 (2017) 721-729 Journal homepage: www.biofueljournal.com Original Research Paper Optimization of biofuel production from corn stover under supply uncertainty in Ontario Jonathan Ranisau1, Emmanuel Ogbe1, Aaron Trainor1, Mohammed Barbouti1, Mohamed Elsholkami1, Ali Elkamel1, 2, Michael Fowler1, * 1 Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Canada. 2 Department of Chemical Engineering, Khalifa University, The Petroleum Institute, Abu Dhabi, UAE. HIGHLIGHTS GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT Examined gasification of corn stover as means to convert waste biomass into fuel. Biorefinery siting locations selected in Ontario counties. MILP model accounts for corn stover supply uncertainty with stochastic programming. At least two biorefinery facilities are required to meet all province demands. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: In this paper, a biofuel production supply chain optimization framework is developed that can supply the fuel demand for 10% Received 14 July 2017 of Ontario. Different biomass conversion technologies are considered, such as pyrolysis and gasification and subsequent hydro Received in revised form 18 September 2017 processing and the Fischer-Tropsch process. A supply chain network approach is used for the modeling, which enables the Accepted 23 October 2017 optimization of both the biorefinery locations and the associated transportation networks. Gasification of corn stover is examined Available online 1 December 2017 to convert waste biomass into valuable fuel. Biomass-derived -

Innovative Methods for Corn Stover Collecting, Handling, Storing and Transporting

April 2004 • NREL/SR-510-33893 Innovative Methods for Corn Stover Collecting, Handling, Storing and Transporting March 2003 J.E. Atchison Atchison Consultants, Inc. J. R. Hettenhaus Chief Executive Assistance, Inc. Charlotte, North Carolina National Renewable Energy Laboratory 1617 Cole Boulevard, Golden, Colorado 80401-3393 303-275-3000 • www.nrel.gov Operated for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy by Midwest Research Institute • Battelle Contract No. DE-AC36-99-GO10337 April 2004 • NREL/SR-510-33893 Innovative Methods for Corn Stover Collecting, Handling, Storing and Transporting March 2003 J.E. Atchison Atchison Consultants, Inc. J. R. Hettenhaus Chief Executive Assistance, Inc. Charlotte, North Carolina NREL Technical Monitor: S.R. Thomas Prepared under Subcontract No. ACO-1-31042-01 National Renewable Energy Laboratory 1617 Cole Boulevard, Golden, Colorado 80401-3393 303-275-3000 • www.nrel.gov Operated for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy by Midwest Research Institute • Battelle Contract No. DE-AC36-99-GO10337 This publication was reproduced from the best available copy Submitted by the subcontractor and received no editorial review at NREL NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. -

Estimating a Value for Corn Stover File A1-70 Corn Stover Is an Abundant Source of Winter Feed for Beef Cows in Iowa

Ag Decision Maker Estimating a Value for Corn Stover File A1-70 Corn stover is an abundant source of winter feed for beef cows in Iowa. When supplemented with protein, vitamins and minerals, stover can supply the nutritional needs of cows that are in moderately good body condition during fall and early winter. Corn stover is also in demand for livestock bedding and as feedstock for the production of ethanol. An obvious advantage of utilizing corn stover is its wide availability and low cost. This has created a small but important market for stover, both as a harvested product and as a standing crop in the field. As with any market, though, a price must be determined. Three general approaches can be used: • What is the value to the purchaser, based on feedstuffs replaced by corn stover? • What is the cost to the seller of harvesting the stover and replacing lost crop nutrients? • What is stover selling for on the market? Price for Harvested Corn Stover Based on Feed Value Comparing the two rations for each cow weight, Corn stover is often sold after it has been harvested, each ton of corn stalks added to the ration usually as large round bales, large square bales, substitutes for about 1.16 tons of legume-grass or small square bales. The following procedure hay. Plus, an additional 0.22 tons of DDGS are estimates the value of baled stover to the buyer added. Thus, the value of a ton of stover can be based on the cost of the feedstuffs it replaces for equated to the value of 1.16 tons of mixed hay, wintering beef cows. -

Corn Stover for Bioenergy Production: Cost Estimates and Farmer Supply Response Jena Thompson and Wallace E

PURDUE EXTENSION RE-3-W Renewable nergy Fueling and Feeding America Through RenewableE Resources Corn Stover for Bioenergy Production: Cost Estimates and Farmer Supply Response Jena Thompson and Wallace E. Tyner Department of Agricultural Economics Purdue University Introduction In 2009, approximately 82% of U.S. energy consumption was from fossil fuels (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2010). Government policy has attempted to reduce this dependency on nonrenewable energy sources through subsidies and mandates of renewable energy sources. Recent attention has been focused on “second generation” biofuels, which are not generated from food sources. Sources of second generation biofuels include crop residues and crops that are grown solely for energy production, called “dedicated energy crops.” Examples of dedicated energy crops are Miscanthus and switchgrass. By requiring fewer reallocations of resources in comparison to biofuels created from food sources, second generation biofuels may have less impact on agricultural commodity markets. We focus on the use of corn stover, the non- grain portion of the corn crop, as a feedstock for bioenergy production. Corn stover could serve as a feedstock for biofuels, as a sub- stitute for coal in producing electric power, or both. In addition to meeting renewable energy goals, use of corn stover for energy production may provide a new source of income for corn growers. We estimate the costs of corn stover harvest and supply, and then use that information to estimate areas of Figure 1. Raking, Baling, and Staging Equipment Corn Stover for Bioenergy Production: Cost Estimates and Renewable nergy Farmer Supply Response • RE-3-W Fueling and Feeding America Through RenewableE Resources stover harvested and changes to farm profit at varying corn Harvest and Supply Cost Estimates stover prices. -

Corn Stover As a Biofuel Feedstock in Iowa: an Analysis of Farmer Interest, Concerns and Price Weiting Lu Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2008 Corn stover as a biofuel feedstock in Iowa: an analysis of farmer interest, concerns and price Weiting Lu Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Lu, Weiting, "Corn stover as a biofuel feedstock in Iowa: an analysis of farmer interest, concerns and price" (2008). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 10948. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/10948 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Corn stover as a biofuel feedstock in Iowa: an analysis of farmer interest, concerns and price by Weiting Lu A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Forestry (Forest Economics and Marketing) Program of Study Committee: Joe P. Colletti, Major Professor Robert Anex Richard Hall Paul Gallagher Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2008 Copyright © Weiting Lu, 2008. All rights reserved. ii TABLES OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT iv CHAPTER 1: OVERVIEW 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.1.1 Statement of Problem 1 1.1.2 Study Objectives 4 1.1.3 Thesis Organization 4 1.2 References -

Cellulosic Ethanol from Corn Stover: Can We Get It Right?

NOVEMBER 2015 R-15-08-A CELLULOSIC ETHANOL FROM CORN STOVER: CAN WE GET IT RIGHT? AUTHOR Loni Kemp EDITOR Sasha Stashwick Acknowledgments Nathanael Greene, Mary Heglar, Barbara Bramble, Jeremy Martin, and the David and Lucille Packard Foundation. About NRDC The Natural Resources Defense Council is a international nonprofit environmental organization with more than 1.4 million members and online activists. Since 1970, our lawyers, scientists, and other environmental specialists have worked to protect the world’s natural resources, public health, and the environment. NRDC has offices in New York City, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, Montana, and Beijing. Visit us at nrdc.org. NRDC Chief Communications Officer: Lisa Benenson NRDC Deputy Director of Communications: Lisa Goffredi NRDC Policy Publications Director: Alex Kennaugh Design and Production: www.suerossi.com © Natural Resources Defense Council 2015 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 PART 1: BEYOND CORN; CHALLENGES IN ENSURING SUSTAINABLE STOVER HARVEST FOR ETHANOL ..................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Lack of Policy Guidance ................................................................................................................................................................ -

Using Corn Stover and Dried Distillers Grains with Solubles

The Professional Animal Scientist 30 ( 2014 ):215–224 © 2014 American Registry of Professional Animal Scientists U sing corn stover and dried distillers grains with solubles to conserve stockpiled forages and improve reproductive performance and progeny 1 growth in fall-calving beef cows P. J. Gunn ,*2 PAS, R. P. Lemenager ,* PAS, and G. A. Bridges †3 * Department of Animal Sciences, Purdue University, 915 West State St., West Lafayette, IN 47907; and † North Central Research and Outreach Center, University of Minnesota, 1861 E HWY 169, Grand Rapids, MN 55744 or corn stover plus DDGS (DG; DDGS Key words: corn stover , dried ABSTRACT at 0.7% of BW/d). Following timed AI, distillers grains with solubles , fertility , Angus-cross, fall-calving beef cows (n CON cows were fed grass hay, and DG progeny growth , stockpile fescue = 153) were used in this experiment. cows were placed on stockpiled tall fescue The objective was to determine whether until grass was exhausted (Julian d 20) INTRODUCTION incorporating a period of corn stover and then fed grass hay. Cow BW and and dried distiller grains with solubles BCS did not differ during the supple- To remain profitable and thrive (DDGS) feeding into a preexisting nu- mentation period. The proportion of within the beef industry, producers tritional program that included grazing cows cycling at breeding-season initiation must find ways to cut production stockpiled tall fescue affects reproductive tended (P = 0.06) to be greater in CON- costs without impairing productiv- performance and progeny growth. On (92.2%) than in DG-treated (80.6%) ity. Because feed, especially harvested Julian d 267 cows were stratified and al- cows. -

Characterization and Measurement of Corn Stover Material Properties Brittany Nicole Schon Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2012 Characterization and Measurement of Corn Stover Material Properties Brittany Nicole Schon Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Agriculture Commons, and the Bioresource and Agricultural Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Schon, Brittany Nicole, "Characterization and Measurement of Corn Stover Material Properties" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 15860. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/15860 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Characterization and measurement of corn stover material properties by Brittany Schon A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Co-Majors: Industrial & Agricultural Technology Biorenewable Resources & Technology Program of Study Committee: Matthew Darr, Major Professor D. Raj Raman Kurt Rosentrater Thomas Brumm Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2012 Copyright ©Brittany Schon, 2012. All rights reserved. ii Table of Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................ -

Life-Cycle Analysis of Ethanol from Corn Stover

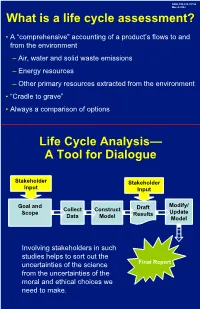

What is a life cycle assessment? • A “comprehensive” accounting of a product’s flows to and from the environment – Air, water and solid waste emissions – Energy resources – Other primary resources extracted from the environment • “Cradle to grave” • Always a comparison of options Life Cycle Analysis— A Tool for Dialogue Stakeholder Stakeholder Input Input Goal and Modify/ Collect Construct Draft Scope Results Update Data Model Model Involving stakeholders in such studies helps to sort out the uncertainties of the science Final Report from the uncertainties of the moral and ethical choices we need to make. Turning Corn Stover to Ethanol • 85% of the residue left after grain harvest (stover) rots on the ground, releasing CO2 • The other 15% is incorporated in soil as organic matter • DOE posits that a certain amount of residue can be collected and used for ethanol production • Our life cycle study asks if the benefits of carbon recycling and fossil energy avoidance can be properly balanced against the lost opportunity for sequestering carbon in soil and improving soil health Life Cycle Analysis— Corn Stover vs Petroleum in Iowa Hydrolysis and Corn Stover Fermentation Biomass Transport Ethanol Feedstock Feedstock Feedstock Fuel Production Transport Conversion Distribution One Mile Traveled Reformulated Crude Transport Oil Refining to Gasoline Crude Oil by barge, pipeline Gasoline Production Assembling the Experts This is the first study to holistically assess the farm, the soil, the conversion technology, and the vehicle technology • Soil -

Feasibility Research Report for Insuring Corn Stover, Straw and Other Crop Residues

Feasibility Report for Insuring Corn Stover, Straw and Other Crop Residues Feasibility Research Report for Insuring Corn Stover, Straw and Other Crop Residues Deliverable 2:Final Feasibility Report Contract Number: D11PX18877 Submitted to: USDA-RMA COTR: Quintrell Hollis 6501 Beacon Drive Kansas City, Missouri64133-4676 (816) 926-3270 Submitted by: Watts and Associates, Inc. 4331 Hillcrest Road Billings, Montana59101 (406) 252-7776 [email protected] Due Date: November 15, 2011 Feasibility Report for Insuring Corn Stover, Straw and Other Crop Residues Table of Contents Section I. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 1 Section II. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 4 II.A. Research Approach........................................................................................................... 10 II.B. Data ................................................................................................................................... 14 II.C. Congressionally Mandated Biofuel Biomass Feedstock Activities .................................. 15 II.D. Reporting Requirements ................................................................................................... 17 Section III. Major Crop Species .................................................................................................... 19 Section IV. Programs Supporting Major Crop