Does Conversation Analysis Have a Role in Computational Linguistics?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies

Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies Working with Autism Spectrum Disorders & Related Communication & Social Skill Challenges Linda Hodgdon, M.Ed., CCC-SLP Speech-Language Pathologist Consultant for Autism Spectrum Disorders [email protected] Learning effective conversation skills ranks as one of the most significant social abilities that students with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) need to accomplish. Educators and parents list the challenges: “Steve talks too much.” “Shannon doesn’t take her turn.” “Aiden talks when no one is listening.” “Brandon perseverates on inappropriate topics.” “Kim doesn’t respond when people try to communicate with her.” The list goes on and on. Difficulty with conversation prevents these students from successfully taking part in social opportunities. What makes learning conversation skills so difficult? Conversation requires exactly the skills these students have difficulty with, such as: • Attending • Quickly taking in and processing information • Interpreting confusing social cues • Understanding vocabulary • Comprehending abstract language Many of those skills that create skillful conversation are just the ones that are difficult as a result of the core deficits in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Think about it. From the student’s point of view, conversation can be very puzzling. Conversation is dynamic. .fleeting. .changing. .unpredictable. © Linda Hodgdon, 2007 1 All Rights Reserved This article may not be duplicated, -

Discussion Notes for Aristotle's Politics

Sean Hannan Classics of Social & Political Thought I Autumn 2014 Discussion Notes for Aristotle’s Politics BOOK I 1. Introducing Aristotle a. Aristotle was born around 384 BCE (in Stagira, far north of Athens but still a ‘Greek’ city) and died around 322 BCE, so he lived into his early sixties. b. That means he was born about fifteen years after the trial and execution of Socrates. He would have been approximately 45 years younger than Plato, under whom he was eventually sent to study at the Academy in Athens. c. Aristotle stayed at the Academy for twenty years, eventually becoming a teacher there himself. When Plato died in 347 BCE, though, the leadership of the school passed on not to Aristotle, but to Plato’s nephew Speusippus. (As in the Republic, the stubborn reality of Plato’s family connections loomed large.) d. After living in Asia Minor from 347-343 BCE, Aristotle was invited by King Philip of Macedon to serve as the tutor for Philip’s son Alexander (yes, the Great). Aristotle taught Alexander for eight years, then returned to Athens in 335 BCE. There he founded his own school, the Lyceum. i. Aside: We should remember that these schools had substantial afterlives, not simply as ideas in texts, but as living sites of intellectual energy and exchange. The Academy lasted from 387 BCE until 83 BCE, then was re-founded as a ‘Neo-Platonic’ school in 410 CE. It was finally closed by Justinian in 529 CE. (Platonic philosophy was still being taught at Athens from 83 BCE through 410 CE, though it was not disseminated through a formalized Academy.) The Lyceum lasted from 334 BCE until 86 BCE, when it was abandoned as the Romans sacked Athens. -

"Context" Within Conversation Analysis

Raclaw: Approaches to "Context" within Conversation Analysis Approaches to "Context" within Conversation Analysis Joshua Raclaw University of Colorado This paper examines the use of "context" as both a participant’s and an analyst’s resource with conversation analytic (CA) research. The discussion focuses on the production and definition of context within two branches of CA, "traditional CA" and "institutional CA". The discussion argues against a single, monolithic understanding of "context" as the term is often used within the CA literature, instead highlighting the various ways that the term is used and understood by analysts working across the different branches of CA. The paper ultimately calls for further reflexive discussions of analytic practice among analysts, similar to those seen in other areas of sociocultural linguistic research. 1. Introduction The concept of context has been a critical one within sociocultural linguistics. The varied approaches to the study of language and social interaction – linguistic, anthropological, sociological, and otherwise – each entail the particulars for how the analyst defines the context in which language is produced. Goodwin and Duranti (1992) note the import of the term within the field of pragmatics (citing Morris 1938; Carnap 1942; Bar-Hillel 1954; Gazdar 1979; Ochs 1979; Levinson 1983; and Leech 1983), anthropological and ethnographic studies of language use (citing Malinowski 1923, 1934; Jakobson 1960; Gumperz and Hymes 1972; Hymes 1972, 1974; and Bauman and Sherzer 1974), and quantitative and variationist sociolinguistics (citing Labov 1966, 1972a, and 1972b).1 To this list we can add a number of frameworks for doing socially-oriented discourse analysis, including conversation analysis (CA), critical discourse analysis (CDA), and discursive psychology (DP). -

PDF of Chapter

Ten-Have-01.qxd 6/6/2007 6:55 PM Page 1 Part 1 Considering CA Ten-Have-01.qxd 6/6/2007 6:55 PM Page 2 Ten-Have-01.qxd 6/6/2007 6:55 PM Page 3 1 Introducing the CA Paradigm Contents What is ‘conversation analysis’? 3 The emergence of CA 5 The development of CA 7 Why do CA? 9 Contrastive properties 9 Requirements 10 Rewards 10 Purpose and plan of the book 11 Exercise 13 Recommended reading 13 Notes 13 Conversation analysis1 (or CA) is a rather specific analytic endeavour. This chapter provides a basic characterization of CA as an explication of the ways in which conversationalists maintain an interactional social order. I describe its emergence as a discipline of its own, confronting recordings of telephone calls with notions derived from Harold Garfinkel’s ethnomethodology and Erving Goffman’s conceptual studies of an interaction order. Later developments in CA are covered in broad terms. Finally, the general outline and purpose of the book is explained. What is ‘conversation analysis’? People talking together,‘conversation’, is one of the most mundane of all topics. It has been available for study for ages, but only quite recently,in the early 1960s, has it gained the serious and sustained attention of scientific investigation. Before then, what was written on the subject was mainly normative: how one should speak, rather than how people actually speak. The general impression was that ordinary conversation is chaotic and disorderly. It was only with the advent of recording devices, and the willingness and ability to study such a mundane phenomenon in depth, that ‘the order of conversation’ – or rather, as we shall see, a multiplicity of ‘orders’ – was discovered. -

Social Communication Skills – the Pragmatics Checklist

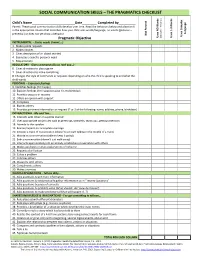

SOCIAL COMMUNICATION SKILLS – THE PRAGMATICS CHECKLIST Child’s Name Date .Completed by . Words Preverbal) Parent: These social communication skills develop over time. Read the behaviors below and place an X - 3 in the appropriate column that describes how your child uses words/language, no words (gestures – - Language preverbal) or does not yet show a behavior. Present Not Uses Complex Uses Complex Gestures Uses Words NO Uses 1 Pragmatic Objective ( INSTRUMENTAL – States needs (I want….) 1. Makes polite requests 2. Makes choices 3. Gives description of an object wanted 4. Expresses a specific personal need 5. Requests help REGULATORY - Gives commands (Do as I tell you…) 6. Gives directions to play a game 7. Gives directions to make something 8. Changes the style of commands or requests depending on who the child is speaking to and what the child wants PERSONAL – Expresses feelings 9. Identifies feelings (I’m happy.) 10. Explains feelings (I’m happy because it’s my birthday) 11. Provides excuses or reasons 12. Offers an opinion with support 13. Complains 14. Blames others 15. Provides pertinent information on request (2 or 3 of the following: name, address, phone, birthdate) INTERACTIONAL - Me and You… 16. Interacts with others in a polite manner 17. Uses appropriate social rules such as greetings, farewells, thank you, getting attention 18. Attends to the speaker 19. Revises/repairs an incomplete message 20. Initiates a topic of conversation (doesn’t just start talking in the middle of a topic) 21. Maintains a conversation (able to keep it going) 22. Ends a conversation (doesn’t just walk away) 23. -

A Pragmatic Stylistic Framework for Text Analysis

International Journal of Education ISSN 1948-5476 2015, Vol. 7, No. 1 A Pragmatic Stylistic Framework for Text Analysis Ibrahim Abushihab1,* 1English Department, Alzaytoonah University of Jordan, Jordan *Correspondence: English Department, Alzaytoonah University of Jordan, Jordan. E-mail: [email protected] Received: September 16, 2014 Accepted: January 16, 2015 Published: January 27, 2015 doi:10.5296/ije.v7i1.7015 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5296/ije.v7i1.7015 Abstract The paper focuses on the identification and analysis of a short story according to the principles of pragmatic stylistics and discourse analysis. The focus on text analysis and pragmatic stylistics is essential to text studies, comprehension of the message of a text and conveying the intention of the producer of the text. The paper also presents a set of standards of textuality and criteria from pragmatic stylistics to text analysis. Analyzing a text according to principles of pragmatic stylistics means approaching the text’s meaning and the intention of the producer. Keywords: Discourse analysis, Pragmatic stylistics Textuality, Fictional story and Stylistics 110 www.macrothink.org/ije International Journal of Education ISSN 1948-5476 2015, Vol. 7, No. 1 1. Introduction Discourse Analysis is concerned with the study of the relation between language and its use in context. Harris (1952) was interested in studying the text and its social situation. His paper “Discourse Analysis” was a far cry from the discourse analysis we are studying nowadays. The need for analyzing a text with more comprehensive understanding has given the focus on the emergence of pragmatics. Pragmatics focuses on the communicative use of language conceived as intentional human action. -

Mathematics: Analysis and Approaches First Assessments for SL and HL—2021

International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme Subject Brief Mathematics: analysis and approaches First assessments for SL and HL—2021 The Diploma Programme (DP) is a rigorous pre-university course of study designed for students in the 16 to 19 age range. It is a broad-based two-year course that aims to encourage students to be knowledgeable and inquiring, but also caring and compassionate. There is a strong emphasis on encouraging students to develop intercultural understanding, open-mindedness, and the attitudes necessary for them LOMA PROGRA IP MM to respect and evaluate a range of points of view. B D E I DIES IN LANGUA STU GE ND LITERATURE The course is presented as six academic areas enclosing a central core. Students study A A IN E E N D N DG two modern languages (or a modern language and a classical language), a humanities G E D IV A O L E I W X S ID U IT O T O G E U or social science subject, an experimental science, mathematics and one of the creative IS N N C N K ES TO T I A U CH E D E A A A L F C T L Q O H E S O R I I C P N D arts. Instead of an arts subject, students can choose two subjects from another area. P G E A Y S A E R S It is this comprehensive range of subjects that makes the Diploma Programme a O S E A Y H T demanding course of study designed to prepare students effectively for university entrance. -

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills As Related to the Development of Executive Function Created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D

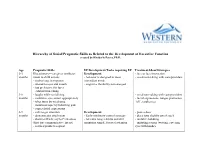

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D. Age Pragmatic Skills EF Development/Tasks requiring EF Treatment Ideas/Strategies 0-3 Illocutionary—caregiver attributes Development: - face to face interaction months intent to child actions - behavior is designed to meet - vocal-turn-taking with care-providers - smiles/coos in response immediate needs - attends to eyes and mouth - cognitive flexibility not emerged - has preference for faces - exhibits turn-taking 3-6 - laughs while socializing - vocal turn-taking with care-providers months - maintains eye contact appropriately - facial expressions: tongue protrusion, - takes turns by vocalizing “oh”, raspberries. - maintains topic by following gaze - copies facial expressions 6-9 - calls to get attention Development: - peek-a-boo months - demonstrates attachment - Early inhibitory control emerges - place toys slightly out of reach - shows self/acts coy to Peek-a-boo - tolerates longer delays and still - imitative babbling (first true communicative intent) maintains simple, focused attention - imitating actions (waving, covering - reaches/points to request eyes with hands). 9-12 - begins directing others Development: - singing/finger plays/nursery rhymes months - participates in verbal routines - Early inhibitory control emerges - routines (so big! where is baby?), - repeats actions that are laughed at - tolerates longer delays and still peek-a-boo, patta-cake, this little piggy - tries to restart play maintain simple, -

A Communication Aid Which Models Conversational Patterns

A communication aid which models conversational patterns. Norman Alm, Alan F. Newell & John L. Arnott. Published in: Proc. of the Tenth Annual Conference on Rehabilitation Technology (RESNA ‘87), San Jose, California, USA, 19-23 June 1987, pp. 127-129. A communication aid which models conversational patterns Norman ALM*, Alan F. NEWELL and John L. ARNOTT University of Dundee, Dundee DD1 4HN, Scotland, U.K. The research reported here was published in: Proceedings of the Tenth Annual Conference on Rehabilitation Technology (RESNA ’87), San Jose, California, USA, 19-23 June 1987, pp. 127-129. The RESNA (Rehabilitation Engineering and Assistive Technology Society of North America) site is at: http://www.resna.org/ Abstract: We have developed a prototype communication system that helps non-speakers to perform communication acts competently, rather than concentrating on improving the production efficiency for specific letters, words or phrases. The system, called CHAT, is based on patterns which are found in normal unconstrained dialogue. It contains information about the present conversational move, the next likely move, the person being addressed, and the mood of the interaction. The system can move automatically through a dialogue, or can offer the user a selection of conversational moves on the basis of single keystrokes. The increased communication speed which is thus offered can significantly improve both the flow of the conversation and the disabled person’s control of the dialogue. * Corresponding author: Dr. N. Alm, University of Dundee, Dundee DD1 4HN, Scotland, UK. A communication aid which models conversational patterns INTRODUCTION The slow rate of communication of people using communication aids is a crucial problem. -

Scientific Discovery in the Era of Big Data: More Than the Scientific Method

Scientific Discovery in the Era of Big Data: More than the Scientific Method A RENCI WHITE PAPER Vol. 3, No. 6, November 2015 Scientific Discovery in the Era of Big Data: More than the Scientific Method Authors Charles P. Schmitt, Director of Informatics and Chief Technical Officer Steven Cox, Cyberinfrastructure Engagement Lead Karamarie Fecho, Medical and Scientific Writer Ray Idaszak, Director of Collaborative Environments Howard Lander, Senior Research Software Developer Arcot Rajasekar, Chief Domain Scientist for Data Grid Technologies Sidharth Thakur, Senior Research Data Software Developer Renaissance Computing Institute University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Chapel Hill, NC, USA 919-445-9640 RENCI White Paper Series, Vol. 3, No. 6 1 AT A GLANCE • Scientific discovery has long been guided by the scientific method, which is considered to be the “gold standard” in science. • The era of “big data” is increasingly driving the adoption of approaches to scientific discovery that either do not conform to or radically differ from the scientific method. Examples include the exploratory analysis of unstructured data sets, data mining, computer modeling, interactive simulation and virtual reality, scientific workflows, and widespread digital dissemination and adjudication of findings through means that are not restricted to traditional scientific publication and presentation. • While the scientific method remains an important approach to knowledge discovery in science, a holistic approach that encompasses new data-driven approaches is needed, and this will necessitate greater attention to the development of methods and infrastructure to integrate approaches. • New approaches to knowledge discovery will bring new challenges, however, including the risk of data deluge, loss of historical information, propagation of “false” knowledge, reliance on automation and analysis over inquiry and inference, and outdated scientific training models. -

Aristotle's Prime Matter: an Analysis of Hugh R. King's Revisionist

Abstract: Aristotle’s Prime Matter: An Analysis of Hugh R. King’s Revisionist Approach Aristotle is vague, at best, regarding the subject of prime matter. This has led to much discussion regarding its nature in his thought. In his article, “Aristotle without Prima Materia,” Hugh R. King refutes the traditional characterization of Aristotelian prime matter on the grounds that Aristotle’s first interpreters in the centuries after his death read into his doctrines through their own neo-Platonic leanings. They sought to reconcile Plato’s theory of Forms—those detached universal versions of form—with Aristotle’s notion of form. This pursuit led them to misinterpret Aristotle’s prime matter, making it merely capable of a kind of participation in its own actualization (i.e., its form). I agree with King here, but I find his redefinition of prime matter hasty. He falls into the same trap as the traditional interpreters in making any matter first. Aristotle is clear that actualization (form) is always prior to potentiality (matter). Hence, while King’s assertion that the four elements are Aristotle’s prime matter is compelling, it misses the mark. Aristotle’s prime matter is, in fact, found within the elemental forces. I argue for an approach to prime matter that eschews a dichotomous understanding of form’s place in the philosophies of Aristotle and Plato. In other words, it is not necessary to reject the Platonic aspects of Aristotle’s philosophy in order to rebut the traditional conception of Aristotelian prime matter. “Aristotle’s Prime Matter” - 1 Aristotle’s Prime Matter: An Analysis of Hugh R. -

LING 211 – Introduction to Linguistic Analysis

LING 211 – Introduction to Linguistic Analysis Section 01: TTh 1:40–3:00 PM, Eliot 103 Section 02: TTh 3:10–4:30 PM, Eliot 103 Course Syllabus Fall 2019 Sameer ud Dowla Khan Matt Pearson pronoun: he or they he office: Eliot 101C Vollum 313 email: [email protected] [email protected] phone: ext. 4018 (503-517-4018) ext. 7618 (503-517-7618) office hours: Wed, 11:00–1:00 Mon, 2:30–4:00 Fri, 1:00–2:00 Tue, 10:00–11:30 (or by appointment) (or by appointment) PREREQUISITES There are no prerequisites for this course, other than an interest in language. Some familiarity with tradi- tional grammar terms such as noun, verb, preposition, syllable, consonant, vowel, phrase, clause, sentence, etc., would be useful, but is by no means required. CONTENT AND FOCUS OF THE COURSE This course is an introduction to the scientific study of human language. Starting from basic questions such as “What is language?” and “What do we know when we know a language?”, we investigate the human language faculty through the hands-on analysis of naturalistic data from a variety of languages spoken around the world. We adopt a broadly cognitive viewpoint throughout, investigating language as a system of knowledge within the mind of the language user (a mental grammar), which can be studied empirically and represented using formal models. To make this task simpler, we will generally treat languages as though they were static systems. For example, we will assume that it is possible to describe a language structure synchronically (i.e., as it exists at a specific point in history), ignoring the fact that languages constantly change over time.