THE Practice of Torture a Threat to the Rule of Law and Democratisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 01 Aug 31.Indd

ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED NEWSPAPER Top Qatari India spin to business team win against visits Kenya England Business | 17 Sport | 27 Sunday 31 August 2014 • 5 Dhu’l-Qa’da 1435 • Volume 19 Number 6174 www.thepeninsulaqatar.com [email protected] | [email protected] Editorial: 4455 7741 | Advertising: 4455 7837 / 4455 7780 Gulf states ready Jeddah meet ‘resolves’ envoy row to help counter jihadist advance GCC foreign ministers agree on terms and criteria for return of envoys to Qatar JEDDAH: Gulf Arab states said yesterday that they were DOHA: The diplomatic dead- ready to help counter advances lock between Qatar and its by jihadists in Syria and Iraq, three GCC peers — Saudi after the US called for a global Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain coalition to fight the militants. — is likely to end soon, with But the six-nation Gulf Kuwait’s First Deputy Prime Cooperation Council said it was Minister and Foreign Minister awaiting details from Washington saying that the ambassadors of and a visit to the region by US the three countries could return Secretary of State Department to Doha “any moment”, Qatar John Kerry to discuss anti-jihad- News Agency (QNA) reported ist cooperation. yesterday. A GCC statement said Gulf The issue was discussed at states are ready to act “against length at the meeting of the for- terrorist threats that face the eign ministers of the GCC states region and the world”. (held in Jeddah yesterday) and The GCC foreign ministers also the terms and criteria for the pledged a readiness to fight “ter- return of the envoys have been rorist ideology which is contrary agreed upon. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-19605-6 — Boundaries of Belonging Sarah Ansari , William Gould Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-19605-6 — Boundaries of Belonging Sarah Ansari , William Gould Index More Information Index 18th Amendment, 280 All-India Muslim Ladies’ Conference, 183 All-India Radio, 159 Aam Aadmi (Ordinary Man) Party, 273 All-India Refugee Association, 87–88 abducted women, 1–2, 12, 202, 204, 206 All-India Refugee Conference, 88 abwab, 251 All-India Save the Children Committee, Acid Control and Acid Crime Prevention 200–201 Act, 2011, 279 All-India Scheduled Castes Federation, 241 Adityanath, Yogi, 281 All-India Women’s Conference, 183–185, adivasis, 9, 200, 239, 261, 263, 266–267, 190–191, 193–202 286 All-India Women’s Food Council, 128 Administration of Evacuee Property Act, All-Pakistan Barbers’ Association, 120 1950, 93 All-Pakistan Confederation of Labour, 256 Administration of Evacuee Property All-Pakistan Joint Refugees Council, 78 Amendment Bill, 1952, 93 All-Pakistan Minorities Alliance, 269 Administration of Evacuee Property Bill, All-Pakistan Women’s Association 1950, 230 (APWA), 121, 202–203, 208–210, administrative officers, 47, 49–50, 69, 101, 212, 214, 218, 276 122, 173, 176, 196, 237, 252 Alwa, Arshia, 215 suspicions surrounding, 99–101 Ambedkar, B.R., 159, 185, 198, 240, 246, affirmative action, 265 257, 262, 267 Aga Khan, 212 Anandpur Sahib, 1–2 Agra, 128, 187, 233 Andhra Pradesh, 161, 195 Ahmad, Iqbal, 233 Anjuman Muhajir Khawateen, 218 Ahmad, Maulana Bashir, 233 Anjuman-i Khawateen-i Islam, 183 Ahmadis, 210, 268 Anjuman-i Tahafuuz Huqooq-i Niswan, Ahmed, Begum Anwar Ghulam, 212–213, 216 215, 220 -

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

y f !, 2.(T I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings MAYA ANGELOU Level 6 Retold by Jacqueline Kehl Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter Contents page Introduction V Chapter 1 Growing Up Black 1 Chapter 2 The Store 2 Chapter 3 Life in Stamps 9 Chapter 4 M omma 13 Chapter 5 A New Family 19 Chapter 6 Mr. Freeman 27 Chapter 7 Return to Stamps 38 Chapter 8 Two Women 40 Chapter 9 Friends 49 Chapter 10 Graduation 58 Chapter 11 California 63 Chapter 12 Education 71 Chapter 13 A Vacation 75 Chapter 14 San Francisco 87 Chapter 15 Maturity 93 Activities 100 / Introduction In Stamps, the segregation was so complete that most Black children didn’t really; absolutely know what whites looked like. We knew only that they were different, to be feared, and in that fear was included the hostility of the powerless against the powerful, the poor against the rich, the worker against the employer; and the poorly dressed against the well dressed. This is Stamps, a small town in Arkansas, in the United States, in the 1930s. The population is almost evenly divided between black and white and totally divided by where and how they live. As Maya Angelou says, there is very little contact between the two races. Their houses are in different parts of town and they go to different schools, colleges, stores, and places of entertainment. When they travel, they sit in separate parts of buses and trains. After the American Civil War (1861—65), slavery was ended in the defeated Southern states, and many changes were made by the national government to give black people more rights. -

Abstract Birds, Children, and Lonely Men in Cars and The

ABSTRACT BIRDS, CHILDREN, AND LONELY MEN IN CARS AND THE SOUND OF WRONG by Justin Edwards My thesis is a collection of short stories. Much of the work is thematically centered around loneliness, mostly within the domestic household, and the lengths that people go to get out from under it. The stories are meant to be comic yet dark. Both the humor and the tension comes from the way in which the characters overreact to the point where either their reality changes a bit to allow it for it, or they are simply fooling themselves. Overall, I am trying to find the best possible way to describe something without actually describing it. I am working towards the peripheral, because I feel that readers believe it is better than what is out in front. BIRDS, CHILDREN, AND LONELY MEN IN CARS AND THE SOUND OF WRONG A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English by Justin Edwards Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2008 Advisor:__________________________ Margaret Luongo Reader: ___________________________ Brian Roley Reader:____________________________ Susan Kay Sloan Table of Contents Bailing ........................................................................1 Dating ........................................................................14 Rake Me Up Before You Go ....................................17 The Way to My Heart ................................................26 Leaving Together ................................................27 The End -

SA8000 Certified Facilities: As of June 30, 2015

SA8000 Certified Facilities: As of June 30, 2015 Date of 1st Name/ Addresses of Date of Initial recertificatio Date of 2nd Date of 3rd Date of 4th Certification internal CB Company Country Address Additional Sites Scope Industry Certification n recertification recertification recertification Body certificate ID D No. 2-142, Chinavutapalli Village- Gannavaram, Krishana District-Vijayawada - Manufacture & Export of ABS Quality 1947 INC. India Andhra Pradesh-India-521 286 -69-1- Leather products Leather 1-Oct-12 Evaluations 47609 67 Duy Tan Street, Hai Chau District, Manufacturing and 28 DA NANG JOINT Da Nang City, processing of garment STOCK COMPANY Vietnam Vietnam products Textiles 24-Jan-13 BSI SA 595078 3' MILLENNIUM via A. Bellatalla 1 56121 Pisa Ospedaletto Supply of local public TRAVEL S.R.L. Italy (PI) ITA transport and bus rental Transportation 27-Mar-14 CISE 585 30027-A01-02 SC PANDORA FASHION SRL 30027-A01 Company: 2 Ana Ipatescu Street 30027-A01-03 SC SIMIZ Tecuci, County Galati (37 km to HQ) FASHION SRL 30027-A01- 30027-A01 SC 30027-A01 Company: 73 Cuza Voda Street 02 : 6 Avantului Street, PANDORA PROD SRL- Focsani, County Vrancea(HQ) Focsani, County Vrancea – TECUCI,GALATI social site without activity ADDRESS 30027-A01-02 : 6 Avantului Street, Focsani, - Pandora Fashion 30027-A01 SC County Vrancea – social site without activity 30027-A01-02 Artera PANDORA PROD SRL- - Pandora Fashion Dj204d, Focsani, County FOSCAI,VRANCEA 30027-A01-02 Artera Dj204d, Focsani, Vrancea – manufacturing ADDRESS (HQ ) County Vrancea – manufacturing site - site - Pandora (2 km to 30027-A01-02 Pandora (2 km to HQ) HQ) SC PANDORA 30027-A01-03 : ARTERA DJ204D, 30027-A01-03 : ARTERA FASHION SRL FOSCANI,County VRANCEA DJ204D, FOSCANI,County 30027-A01-03 SC (2 km to HQ location) VRANCEA 30027-A01, 30027- SIMIZ FASHION SRL (2 km to HQ location) A01-02; 30027- Romania Textile Textiles 10-Dec-14 Intertek A01-03 Design, installation and maintenance electrical systems in medium and low via Arco della Ciambella, 13 - 00186 - Roma voltage - Maintenance Electrical 3M Elettrotecnica S.r.l. -

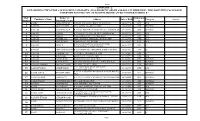

Candidate's Name Address Date of Birth Category 1 2 3

Sheet1 "ANNEXURE ‘A’ LIST SHOWING THE DETAILS OF ELIGIBLE CANDIDATES ( IN ALPHABETIC ORDER AND ROLL NUMBER WISE) WHO HAVE BEEN CALLED FOR INTERVIEW FOR THE POST OF PROCESS SERVER AS PER NOTIFIED SCHEDULE" Roll Father’ s/ Qualificatio Candidate’s Name Address Date of Birth Category Remarks Number Husband’s Name n 1 AABID KAMAAL KHAN SUNARI TEH TAURU DISTT MEWAT NUH 08/03/1995 10TH BCB 2 AADITYA SANJAY SINGH 2/298 AARYA NAAGR, SONIPAT 10/05/2002 12TH GENERAL 3 AAKASH RAJESH KUMAR H NO 723, KRISHNA NAGAR SEC 20A, FARIDABAD 07/18/1999 12TH GENERAL 4 AAKASH SAMPAT H NO 374 SEC 86 VILL. BUDENA FARIDABAD 08/03/1998 10TH BCB 5 AAKASH RAKESH VILL. BAROLI, SEC 80, FARIDABAD 01/02/1998 10TH BCA 6 AAKASH SUNDER LAL VILL GHARORA, TEH BALLABGRAH, FBD 08/12/1999 10TH BCA 7 AAKASH AJAY KUMAR ADARSH COLONY PALWAL 03/31/1997 B,SC BCA H NO D 396 WARD NO 12 NEAR PUNJABI AAKASH VIDHUR 06/07/1999 10TH SC 8 DHARAMSHALA, CAMP, PALWAL 9 AAKASH NIRANJAN KUMAR H NO 164 WAR NO 9 FIROZPUR JHIRKA, MEWAT 08/08/1995 12TH SC 10 AAKASH KUNWAR PAL VILL ARUA, CHANDAPUR, FBD 01/15/2001 10TH SC 11 AAKASH SURENDER KHATI PATTI, TIGAON, FBD 01/19/1999 12TH BCB 12 AAKASH GANGA RAM BHIKAM COLONY, BLB, FBD 05/25/2001 10TH GENERAL 13 AAKASH SHYAM DUTT 263 ARYA NAGAR, WAR NO 4 HODAL PALWAL 11/21/1997 10TH GENERAL 14 AAKASH SHARMA KISHAN CHAND 232 , HBC COLONY SIRSA 05/09/1989 12TH GENERAL VILL. -

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Wednesday, March 18, 2009 2:36:33PM School: Churchland Academy Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Quiz Word Number Lang. Title Author IL ATOS BL Points Count F/NF 9318 EN Ice Is...Whee! Greene, Carol LG 0.3 0.5 59 F 9340 EN Snow Joe Greene, Carol LG 0.3 0.5 59 F 36573 EN Big Egg Coxe, Molly LG 0.4 0.5 99 F 9306 EN Bugs! McKissack, Patricia C. LG 0.4 0.5 69 F 86010 EN Cat Traps Coxe, Molly LG 0.4 0.5 95 F 9329 EN Oh No, Otis! Frankel, Julie LG 0.4 0.5 97 F 9333 EN Pet for Pat, A Snow, Pegeen LG 0.4 0.5 71 F 9334 EN Please, Wind? Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 55 F 9336 EN Rain! Rain! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 63 F 9338 EN Shine, Sun! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 66 F 9353 EN Birthday Car, The Hillert, Margaret LG 0.5 0.5 171 F 9305 EN Bonk! Goes the Ball Stevens, Philippa LG 0.5 0.5 100 F 7255 EN Can You Play? Ziefert, Harriet LG 0.5 0.5 144 F 9314 EN Hi, Clouds Greene, Carol LG 0.5 0.5 58 F 9382 EN Little Runaway, The Hillert, Margaret LG 0.5 0.5 196 F 7282 EN Lucky Bear Phillips, Joan LG 0.5 0.5 150 F 31542 EN Mine's the Best Bonsall, Crosby LG 0.5 0.5 106 F 901618 EN Night Watch (SF Edition) Fear, Sharon LG 0.5 0.5 51 F 9349 EN Whisper Is Quiet, A Lunn, Carolyn LG 0.5 0.5 63 NF 74854 EN Cooking with the Cat Worth, Bonnie LG 0.6 0.5 135 F 42150 EN Don't Cut My Hair! Wilhelm, Hans LG 0.6 0.5 74 F 9018 EN Foot Book, The Seuss, Dr. -

The Path of Lucius Park and Other Stories of John Valley

THE PATH OF LUCIUS PARK AND OTHER STORIES OF JOHN VALLEY By Elijah David Carnley Approved: Sybil Baker Thomas P. Balázs Professor of English Professor of English (Chair) (Committee Member) Rebecca Jones Professor of English (Committee Member) J. Scott Elwell A. Jerald Ainsworth Dean of College of Arts and Sciences Dean of the Graduate School THE PATH OF LUCIUS PARK AND OTHER STORIES OF JOHN VALLEY By Elijah David Carnley A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master’s of English The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, Tennessee May 2013 ii Copyright © 2013 By Elijah David Carnley All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT This thesis comprises a writer’s craft introduction and nine short stories which form a short story cycle. The introduction addresses the issue of perspective in realist and magical realist fiction, with special emphasis on magical realism and belief. The stories are a mix of realism and magical realism, and are unified by characters and the fictional setting of John Valley, FL. iv DEDICATION These stories are dedicated to my wife Jeana, my parents Keith and Debra, and my brother Wesley, without whom I would not have been able to write this work, and to the towns that served as my home in childhood and young adulthood, without which I would not have been inspired to write this work. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my Fiction professors, Sybil Baker and Tom Balázs, for their hard work and patience with me during the past two years. -

Raw Thought: the Weblog of Aaron Swartz Aaronsw.Com/Weblog

Raw Thought: The Weblog of Aaron Swartz aaronsw.com/weblog 1 What’s Going On Here? May 15, 2005 Original link I’m adding this post not through blogging software, like I normally do, but by hand, right into the webpage. It feels odd. I’m doing this because a week or so ago my web server started making funny error messages and not working so well. The web server is in Chicago and I am in California so it took a day or two to get someone to check on it. The conclusion was the hard drive had been fried. When the weekend ended, we sent the disk to a disk repair place. They took a look at it and a couple days later said that they couldn’t do anything. The heads that normally read and write data on a hard drive by floating over the magnetized platter had crashed right into it. While the computer was giving us error messages it was also scratching away a hole in the platter. It got so thin that you could see through it. This was just in one spot on the disk, though, so we tried calling the famed Drive Savers to see if they could recover the rest. They seemed to think they wouldn’t have any better luck. (Please, plase, please, tell me if you know someplace to try.) I hadn’t backed the disk up for at least a year (in fairness, I was literally going to back it up when I found it giving off error messages) and the thought of the loss of all that data was crushing. -

Asie Observatoire Pour La Protection Des Défenseurs Des Droits De L'homme Rapport Annuel 2011

ASIE OBSERVATOIRE POUR LA PROTECTION DES DÉFENSEURS DES DROITS DE L'HOMME RAPPORT ANNUEL 2011 367 ANALYSE RÉGIONALE ASIE OBSERVATOIRE POUR LA PROTECTION DES DÉFENSEURS DES DROITS DE L'HOMME RAPPORT ANNUEL 2011 En 2010-2011, les élections qui se sont déroulées dans plusieurs pays de la région Asie ont souvent été accompagnées de vastes fraudes et d’irrégu- larités, avec un renforcement des restrictions pesant sur les libertés d’ex- pression et de réunion, tandis que les Gouvernements ont muselé encore davantage l’opposition et les voix dissidentes (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Birmanie, Malaisie, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Viet Nam). En Birmanie en particulier, les premières élections nationales tenues depuis 20 ans, en novembre 2010, se sont avérées ni libres ni équitables, ayant été entachées d’une série d’irrégularités et de restrictions draconiennes sur la liberté d’as- sociation et de la presse. Bien que l’année 2010 ait aussi été marquée par la libération historique après les élections de l’assignation à domicile de la cheffe de l’opposition, Mme Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, la Birmanie attend toujours une amnistie générale, plus de 2 000 prisonniers politiques étant maintenus en détention. Une sécurité publique inadéquate et l’absence d’un climat propice aux défenseurs des droits de l’Homme ont pesé de manière significative sur le travail des militants dans toute la région (Afghanistan, Inde, Népal, Pakistan, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thaïlande), notamment dans les zones échappant en partie à l’autorité gouvernementale, telles que les régions méridionales -

General Assembly Distr.: General 23 May 2011

United Nations A/HRC/17/NGO/25 General Assembly Distr.: General 23 May 2011 English only Human Rights Council Seventeenth session Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Written statement* submitted by the Asian Legal Resource Centre (ALRC), a non-governmental organization in general consultative status The Secretary-General has received the following written statement which is circulated in accordance with Economic and Social Council resolution 1996/31. [16 May 2011] * This written statement is issued, unedited, in the language(s) received from the submitting non-governmental organization(s). GE.11-13339 A/HRC/17/NGO/25 Pakistan: Extra-judicial killings ongoing with impunity, notably in Balochistan 1. The Asian Legal Resource Centre (ALRC) wishes to bring to the attention of the Human Rights Council grave concerns related to the numerous allegations of extra-judicial killings that it has received in the last 12 months, notably from the province of Balochistan in Pakistan. Extra-judicial killings are typically the end-point of a string of human rights abuses that include abduction or arbitrary arrest, forced disappearance and torture. Disappeared persons’ bodies are often dumped on the roadside, riddled with bullets. This pattern of abuse has reportedly become a routine method used by Pakistan’s intelligence agencies. In the past eight months, over 120 persons are thought to have been killed extra- judicially following abduction and disappearance by the State. The ALRC estimates that thousands of people are reported to have been subjected to enforced disappearance in recent years, in particular in resource-rich Balochistan. -

GID 2016.Pdf

SUPPLIERS & GLASSWORKS COMPLETE GLASS PROFILES DIRECTORY th Special cast irons & alloys 27 annual for glass moulds edition S Suppliers’ Profiles S Yellow Pages S Agents & 2 - Copia omaggio € sales offices "ÉÊUÊÊ S Glassworks’ addresses S Associations *ÃÌiÊÌ>>iÊ-«>ÊÊ-«i`âiÊÊ>LL>iÌÊ«ÃÌ>iÊÊÇä¯ÊÊ Fonderie Valdelsane S.p.A. Strada di Gabbricce, 6 - P.O. BOX 30 - 53035 MONTERIGGIONI (Siena) - ITALY Tel. +39.0577.304730 - Fax. +39.0577.304755 - [email protected] NARIO DE N www.fonderievaldelsane.com FO Supplemento al n. 168 - no. 4/2016 di Glass Machinery Plants & Accessories, Smartenergy S.r.l., Dir. Resp. Marco Pinetti, Supplemento al n. 168 - no. 4/2016 di Glass MachineryDir. Plants & Accessories, Smartenergy S.r.l., At home in the world of glass NIKOLAUS SORG EME MASCHINENFABRIK INTERNATIONAL GmbH FEUERUNGSBAU SORG KERAMIK GmbH & Co KG CLASEN GmbH UND SERVICE GmbH SERVICE GmbH Nikolaus Sorg GmbH & Co. KG | Stoltestraße 23 | 97816 Lohr am Main/Germany | Phone: +49 (0) 9352 507 0 | E-Mail: [email protected] | www.sorg.de , Tomorrow s Technology Today The World’s leading glass companies come to FIC with their Electric Boost/Heating projects E-Glass Installations up to 3,500kW in oxy- Display Glass Numerous installations of fired furnaces for extra tonnage and improving up to 1000kW installed power for TFT/LCD glasses glass quality to eliminate strand breakages. using tin oxide electrode blocks to achieve exceptional glass quality. Container Glass Various installations in flint and coloured glasses, up to 2,500kW for Electric Furnaces Developing new increased output and quality. furnace designs for most glass types, including opal.