Christmas Evans (1766 - 1838)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SA/SEA Non Technical

Revised Local 2018-2033 Development Plan NonNon TechnicalTechnical SummarySummary -- DepositDeposit PlanPlan Sustainability Appraisal / Sustainability Appraisal Environmental Strategic (SA/SEA) Assessment January 2020 / Sustainability Appraisal Environmental Strategic (SA/SEA) Assessment Addendum Sustainability Appraisal (including Strategic Environmental Assessment -SA), Report. A further consultation period for submitting responses to the SA/SEA as part of the Deposit Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 – 2033 is now open. Representations submitted in respect of the further consultation on the Sustainability Appraisal (including Strategic Environmental Assessment -SA) must be received by 4:30pm on the 2nd October 2020. Comments submitted after this date will not be considered. Contents Revised Local Development Plan 3 Sustainability Appraisal (SA) and Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) 3 The Sustainability Appraisal (SA) Process 4 Stage A - SA Scoping Report 5 Policy Context 6 Baseline Information 7 Carmarthenshire’s Wellbeing Plan 9 Issues and Opportunities 10 The Sustainability Framework 11 Stage B—Appraisal of Alternatives 12 SA of Vision and Objectives 13 SA of Growth Options 16 SA of Spatial Options 18 Hybrid Option—Balanced Community and Sustainable Growth 25 SA of Strategic Policies 27 Overall Effects of the Preferred Strategy 28 Stage C—Appraisal of the Deposit Plan 30 SA of the Deposit Plan Vision and Strategic Objectives 31 SA of the Preferred Growth Strategy of the Deposit Plan 32 SA of the Preferred Spatial Option of the Deposit Plan 33 SA of the Deposit Plan Strategic Policies 33 SA of the Deposit Plan Specific Policies 35 SA of the Deposit Plan Proposed Allocations 39 Overall Effects of the Deposit LDP 45 SA Monitoring Framework 46 Consultation and Next Steps 47 2 Revised Local Development Plan Carmarthenshire County Council has begun preparing the Revised Local Development Plan (rLDP). -

Mae'r E-Bost Hwn Ac Unrhyw Atodiadau Yn Gyfrinachol Ac Wedi'u Bwriadu at Ddefnydd Yr Unigolyn Y'u Cyfeiriwyd Ato/Ati Yn Unig

Dear Sir / Madam Please find attached the Council’s Local Impact Report and associated Appendices which was endorsed by members of the Council’s Planning Committee on 5th November 2015. Please can you acknowledge receipt. Kind Regards Richard Jones Development Management Officer / Swyddog Rheoli Datblygu Planning Services, 8 Spilman Street, Carmarthen SA31 1JY Tel: 01267 228892 (ext. 2892) E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.carmarthenshire.gov.uk/planning Mae'r e-bost hwn ac unrhyw atodiadau yn gyfrinachol ac wedi'u bwriadu at ddefnydd yr unigolyn y'u cyfeiriwyd ato/ati yn unig. Os derbyniwch y neges hon trwy gamgymeriad, rhowch wybod i'r sawl a'i hanfonodd ar unwaith, dil?wch y neges o'ch cyfrifiadur a dinistriwch unrhyw gop?au papur ohoni. Ni ddylech ddangos yr e-bost i neb arall, na gweithredu ar sail y cynnwys. Eiddo'r awdur yw unrhyw farn neu safbwyntiau a fynegir, ac nid ydynt o reidrwydd yn cynrychioli safbwynt y Cyngor. Dylech wirio am firysau eich hunan cyn agor unrhyw atodiad. Nid ydym yn derbyn unrhyw atebolrwydd am golled neu niwed a all fod wedi'i achosi gan firysau meddalwedd neu drwy ryng-gipio'r neges hon neu ymyrryd ? hi. This e-mail and any attachments are confidential and intended solely for the use of the individual to whom it is addressed. If received in error please notify the sender immediately, delete the message from your computer and destroy any hard copies. The e-mail should not be disclosed to any other person, nor the contents acted upon. Any views or opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Council. -

Sustainability Appraisal Report of the Deposit LDP November 2019

Carmarthenshire Revised Local Development Plan (LDP) Sustainability Appraisal Report of the Deposit LDP November 2019 1. Introduction This document is the Sustainability Appraisal (SA) Report, consisting of the joint Sustainability Appraisal (SA) and Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA), of Carmarthenshire Council’s Deposit Revised Local Development Plan (rLDP).The SA/SEA is a combined process which meets both the regulatory requirements for SEA and SA. The revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan is a land use plan which outlines the location and quantity of development within Carmarthenshire for a 15 year period. The purpose of the SA is to identify any likely significant economic, environmental and social effects of the LDP, and to suggest relevant mitigation measures. This process integrates sustainability considerations into all stages of LDP preparation, and promotes sustainable development. This fosters a more inclusive and transparent process of producing a LDP, and helps to ensure that the LDP is integrated with other policies. This combined process is hereafter referred to as the SA. This Report accompanies, and should be read in conjunction with, the Deposit LDP. The geographical scope of this assessment covers the whole of the County of Carmarthenshire, however also considers cross-boundary effects with the neighbouring local authorities of Pembrokeshire, Ceredigion and Swansea. The LDP is intended to apply until 2033 following its publication. This timescale has been reflected in the SA. 1.1 Legislative Requirements The completion of an SA is a statutory requirement for Local Development Plans under Section 62(6) of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 20041, the Town and Country Planning (LDP) (Wales) Regulations 20052 and associated guidance. -

Full Property Address Current Rateable Value Company Name

Current Rateable Full Property Address Company Name Value C.R.S. Supermarket, College Street, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 3AB 89000 Cws Ltd Workshop & Stores, Foundry Road, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 2LS 75000 Messrs T R Jones (Betws) Ltd 23/25, Quay Street, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 3DB 33750 Boots Uk Limited Old Tinplate Works, Pantyffynnon Road, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, 64000 Messrs Wm Corbett & Co Ltd 77, Rhosmaen Street, Llandeilo, Carmarthenshire, SA19 6LW 49000 C K`S Supermarket Ltd Warehouse, Station Road, Llandeilo, Carmarthenshire, 32000 Llandeilo Builders Supplies Ltd Golf Club, Glynhir Road, Llandybie, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 2TE 31250 The Secretary Penygroes Concrete Products, Norton Road, Penygroes, Llanelli, Carmarthenshire, SA14 7RU 85500 The Secretary Pant Glas Hall, Llanfynydd, Carmarthen, Carmarthenshire, 75000 The Secretary, Lightcourt Ltd Unit 4, Pantyrodin Industrial Estate, Llandeilo Road, Llandybie, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 3JG 35000 The Secretary, Amman Valley Fabrication Ltd Cross Hands Business Park, Cross Hands, Llanelli, Carmarthenshire, SA14 6RB 202000 The Secretary Concrete Works (Rear, ., 23a, Bryncethin Road, Garnant, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 1YP 33000 Amman Concrete Products Ltd 17, Quay Street, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 3DB 54000 Peacocks Stores Ltd Pullmaflex Parc Amanwy, New Road, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 3ER 152000 The Secretary Units 27 & 28, Capel Hendre Industrial Estate, Capel Hendre, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 3SJ 133000 Quinshield -

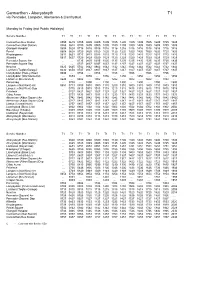

Carmarthen - Aberystwyth T1 Via Pencader, Lampeter, Aberaeron & Llanrhystud

Carmarthen - Aberystwyth T1 via Pencader, Lampeter, Aberaeron & Llanrhystud. Monday to Friday (not Public Holidays) Service Number T1 T1 T1 T1 T1 T1 T1 T1 T1 T1 T1 T1 T1 T1 Carmarthen Bus Station 0555 0615 0705 0805 0905 1005 1105 1205 1305 1405 1505 1605 1705 1805 Carmarthen (Rail Station) 0558 0618 0709 0809 0909 1009 1109 1209 1309 1409 1509 1609 1709 1809 Glangwili Hospital 0604 0624 0716 0816 0916 1016 1116 1216 1316 1416 1516 1616 1716 1816 Peniel 0608 0628 0720 0820 0920 1020 1120 1220 1320 1420 1520 1620 1720 1820 Rhydargaeau 0611 0631 0723 0823 0923 1023 1123 1223 1323 1423 1523 1623 1723 1823 Alltwalis 0617 0637 0729 0829 0929 1029 1129 1229 1329 1429 1529 1629 1729 1829 Pencader Square Arr .... .... 0735 0835 0935 1035 1135 1235 1335 1435 1535 1635 1735 1835 Pencader Square Dep .... .... 0737 0837 0937 1037 1137 1237 1337 1437 1537 1637 1737 1837 New Inn 0625 0645 0742 0842 0942 1042 1142 1242 1342 1442 1542 1642 1742 1842 Llanllwni (Tegfan Garage) 0630 0650 0747 0847 0947 1047 1147 1247 1347 1447 1547 1647 1747 1847 Llanybydder (Heol-y-Gaer) 0638 .... 0756 .... 0956 .... 1156 .... 1356 .... 1556 .... 1756 .... Llanybydder (War Memorial) .... 0659 .... 0856 .... 1056 .... 1256 .... 1456 .... 1656 .... 1856 Llanwnen (Bro Granell) 0644 .... 0802 .... 1002 .... 1202 .... 1402 .... 1602 .... 1802 .... Pencarreg .... 0703 .... 0900 .... 1100 .... 1300 .... 1500 .... 1700 .... 1900 Lampeter (Nat West) Arr 0651 0713 0809 0910 1009 1110 1209 1310 1409 1510 1609 1710 1809 1910 Lampeter (Nat West) Dep .... 0715 0815 0915 1015 1115 1215 1315 1415 1515 1615 1715 1815 1915 Felinfach ... -

Deposit - Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 – 2033

Deposit - Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 – 2033 Draft for Reporting Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 - 2033 Foreword To be inserted Deposit Draft – Version for Reporting i Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 - 2033 Contents: Page No: Policy Index iii How to View and Comment on the Deposit Revised LDP vi 1. Introduction 1 2. What is the Deposit Plan? 3 3. Influences on the Plan 7 4. Carmarthenshire - Strategic Context 12 5. Issues Identification 25 6. A Vision for ‘One Carmarthenshire’ 28 7. Strategic Objectives 30 8. Strategic Growth and Spatial Options 36 9. A New Strategy 50 10. The Clusters 62 11. Policies 69 12. Monitoring and Implementation 237 13. Glossary 253 Appendices: Appendix 1: Context – Legislative and National Planning Policy Guidance Appendix 2: Regional and Local Strategic Context Appendix 3: Supplementary Planning Guidance Appendix 4: Minerals Sites Appendix 5: Active Travel Routes Appendix 6: Policy Assessment Appendix 7: Housing Trajectory Appendix 8: Waste Management Facilities Deposit Draft – Version for Reporting ii Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 - 2033 Policy Index Page No. Strategic Policy – SP1: Strategic Growth 70 • SG1: Regeneration and Mixed Use Sites 72 • SG2: Reserve Sites 73 • SG3: Pembrey Peninsula 75 Strategic Policy – SP2: Retail and Town Centres 76 • RTC1: Carmarthen Town Centre 82 • RTC2: Protection of Local Shops and Facilities 84 • RTC3: Retail in Rural Areas 85 Strategic Policy – SP3: A Sustainable Approach to Providing New -

Beric House Llanpumsaint, Nr Carmarthen, Carmarthenshire, SA33 6BY Asking Price £250,000

Beric House Llanpumsaint, Nr Carmarthen, Carmarthenshire, SA33 6BY Asking Price £250,000 A CONVENIENTLY LOCATED 4/5 BEDROOM DETACHED family sized HOUSE (in need of updating) built on a GENEROUS PLOT with rural views to the rear. First time on the market in decades; situated on the edge of the poular Gwili valley village of Llanpumsaint, this substantial family sized property comprises: SITTING ROOM, OPEN PLAN KITCHEN, DINING ROOM, UTILITY ROOM, GROUND FLOOR CLOAKROOM, 4/5 BEDROOMS, FAMILY BATHROOM, ATTACHED GARAGE / WORKSHOP and benefits from: FULL OIL CENTRAL HEATING, SECONDARY GLAZING, EXTENSIVE LAWNED GROUNDS (the whole plot extending in all to approx 0.4 of an acre), AMPLE OFF ROAD PARKING, RURAL VIEWS of the surrounding countryside. LOCATION & DIRECTIONS KITCHEN / BREAKFAST ROOM Conveniently set at OS Grid Ref SN 419 292 on the edge of 13'10" x 12'10" (4.224 x 3.937) the popular Gwili valley village of Llanpumsaint. The small village offers a convenient Primary School and is just 7 miles (10 - 15 minutes by car) from the county town of Carmarthen. As such, Carmarthen offers a fantastic range of amenities inc a mainline train station, a regional hospital, 4 supermarkets, Leisure Centre, Multi-screen cinema etc. In the other direction, the Teifi valley town of Llandysul is approx 8 miles away. From Carmarthen, take the A484 as if heading towards Newcastle Emlyn or Cardigan. Proceed for approx a mile and a half into the village of Bronwydd Arms and turn right as if heading towards the "Steam Railway". Drive through the village (passing the steam railway) and proceed for approx 1 mile before turning left signposted "Llanpumsaint". -

Revival and Its Fruit

REVIVAL AND ITS FRUIT Revival by Emyr Roberts The Revival of 1762 and William Williams of Pantycelyn by R. Geraint Gruffydd Evangelical Library of Wales 1981 © Evangelical Library of Wales, 1981 First published-1981 ISBN 0 900898 58 5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Evangelical Library of Wales. Cover design by JANET PRICE Published by the Evangelical Library of Wales, Bryntirion, Bridgend. Mid Glamorgan, CF31 4DX Printed by Talbot Printing Co. Ltd., Port Talbot, West Glamorgan. [page 3] Revival Emyr Roberts REVIVAL is probably more remote from the thinking of the churches today than it has been since the beginning of Nonconformity in our land, and certainly since the Methodist Revival of over two centuries ago.∗ When at the end of October 1904, with the fire of revival in his heart, Evan Roberts felt compelled to leave the preparatory school in Castellnewydd Emlyn, Carmarthenshire, to hold revival meetings in his home town of Casllwchwr in Glamorgan, Evan Phillips the minister, who had celebrated his seventy- fifth birthday the previous week and well remembered the 1859 Revival, recognized the Spirit in the young student and advised him to go. One wonders what advice he would be given today, were he a student under the same spiritual compulsion. Some of the leaders of the 1904 Revival, such as Joseph Jenkins and W. W. Lewis, had been under the tuition of men like Thomas Charles Edwards in Aberystwyth and John Harris Jones in Trefeca, of whom the former had been profoundly affected by the '59 Revival, and the latter a leader in that same Revival. -

Gwynfaes, New Inn, Pencader SA39

Gwynfaes, New Inn, Pencader SA39 9AZ Offers in the region of £145,000 • Deceptively Spacious Two Bedroom Detached Bungalow • Rural Village Location • Oil Central Heating & Double Glazing • Gated Driveway & Lawn To Side • EER 45 CR/KH/52279/181016 Range of base units with drainage are connected worktop over, breakfast to the property. Oil fired DESCRIPTION bar, stainless steel sink central heating system. A spacious detached and drainer with mixer bungalow located within tap, four ring gas hob, VIEWING the rural village of New Worcester oil fired boiler, By appointment with the Inn which lies space for washing selling Agents on 01267 approximately 12 miles machine and fridge 233 111 or e-mail north of Carmarthen. freezer, two double carmarthen@johnfrancis. Offering good sized glazed windows to front, co.uk rooms & garden with external door to side. parking. Briefly OUR OFFICE HOURS comprising kitchen/diner, Monday to Friday LIVING ROOM 9:00am to 5:30pm living room, family 17'7 x 13' (5.36m x bathroom and two double Saturday 9:00am to 3.96m) 4:00pm bedrooms. The Gas fireplace and bungalow, which requires surround, double glazed FACEBOOK &TWITTER some updating, benefits window to rear, radiator. Follow us on twitter from oil fired central @JohnFrancisCarm or heating and double BATHROOM on facebook glazing. There is an easy 8'6 x 7'3 (2.59m x 2.21m) www.facebook.com/ to maintain level garden Corner bath with shower JohnFrancisEstateAgents to the side of the property over, low level WC, wash along with parking for hand basin, radiator, TENURE several vehicles and localised wall tiles, tiled We are advised that the enjoys countryside views floor, obscure double property is Freehold to the rear. -

Deposit - Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 – 2033

Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 - 2033 Deposit - Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 – 2033 Draft for Reporting Deposit Draft – Version for Reporting 1 Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 - 2033 Foreword To be inserted Deposit Draft – Version for Reporting 2 Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 - 2033 Contents Policy Index List of Tables and Figures Abbreviations How to View and Comment on the Deposit Revised LDP 1. Introduction 2. What is the Deposit Plan? 3. Influences on the Plan 4. Carmarthenshire - Strategic Context 5. Issues Identification 6. A Vision for ‘One Carmarthenshire’ 7. Strategic Objectives 8. Strategic Growth and Spatial Options 9. A New Strategy 10. The Clusters 11. Policies Monitoring and Implementation Glossary Appendices: Deposit Draft – Version for Reporting 3 Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 - 2033 Policy Index Policy Index Strategic Policy – SP 1: Strategic Growth SG1: Regeneration and Mixed Use Sites SG2: Reserve Sites Strategic Policy – SP 2: Retail and Town Centres RTC1: Carmarthen Town Centre RTC2: Protection of Local Shops and Facilities RTC3: Retail in Rural Areas Strategic Policy – SP 3: A Sustainable Approach to Providing New Homes HOM1: Housing Allocations HOM2: Housing within Development Limits HOM3: Homes in Rural Villages HOM4: Homes in Non-Defined Rural Settlements HOM5: Conversion or Subdivision of Existing Dwellings HOM6: Specialist Housing HOM7: Renovation of Derelict or Abandoned Dwellings HOM8: Residential -

Perfformwyr Penigamp

Rhifyn 279 - 60c www.clonc.co.uk Rhagfyr 2009 Papur Bro ardal plwyfi: Cellan, Llanbedr Pont Steffan, Llanbedr Wledig, Llanfair Clydogau, Llangybi, Llanllwni, Llanwenog, Llanwnnen, Llanybydder, Llanycrwys ac Uwch Gaeo a Phencarreg Plant Cadwyn Llyfr Tudalen 16 Mewn arall o Defi Angen gyfrinachau Lango Tudalen 2 Tudalen 20 Perfformwyr Penigamp Einir Ryder a Teleri Morris-Thomas, CFfI Pontsian a ddaeth yn Elliw Dafydd, CFfI Silian a enillodd ar y 3ydd yn y Ddeuawd Doniol dan 26 oed yn Eisteddfod Cymru. Llefaru o dan 16 yn Eisteddfod Cymru. Rhian Davies ac Owain Davies, CFfI Llanllwni yn ennill y Stori a Sain dan 26 yn Eisteddfod Cymru, a Rhian yn ennill ar y Llefaru dan 21 hefyd. ‘Hwrdd Du Ffynnonbedr’ - Ffilm fuddugol Ysgol Ffynnonbedr - Gŵyl Ffilmiau Ceredigion 2009 Carol, Cerdd a Chân Eglwys Sant Pedr, Llambed Nos Sadwrn 19 Rhagfyr 2009 am 7 o’r gloch, yng nghwmni: Côr Merched Corisma, Elin a Guto Williams, Plant Ysgol Ffynnonbedr, Aelodau’r Urdd, Disgyblion yr Ysgol Gyfun. Pris Mynediad £4. Elw at Gymorth Cristnogol. Plant Mewn Angen Ar ddiwrnod Plant Mewn Angen - disgyblion yr Ysgol Gyfun ar daith gerdded, disgyblion Ysgol Llanwnnen yn gorchuddio Pydsey gydag arian mân, Ysgol Cwrtnewydd yn eu pyjamas, Ysgol Llanwenog mewn Sioe Dalent, Pudsey mewn arian yn Ysgol Ffynnonbedr ac Ysgol Carreg Hirfaen yn eu dillad dwl. Wrth i Clonc fynd i’r wasg cyhoeddodd Goronwy a Beti Evans fod y cyfanswm yn lleol yn £17,924.00 ac yn cynyddu’n ddyddiol. Nadolig Llawen a Blwyddyn Newydd Dda oddi wrth wirfoddolwyr Papur Bro Clonc. Diolch yn fawr i bawb am eu cefnogaeth drwy’r flwyddyn. -

Favoured with Frequent Revivals

FAVOURED WITH FREQUENT REVIVALS Map of Wales showing some places mentioned in the text FAVOURED WITH FREQUENT REVIVALS Revivals in Wales 1762-1862 D. Geraint Jones THE HEATH CHRISTIAN TRUST THE HEATH CHRISTIAN TRUST C/O 31 Whitchurch Road, Cardiff, CF14 3JN © D. Geraint Jones 2001 First Published 2001 ISBN 0 907193 10 2 Contents Preface 7 Abbreviations 8 Favoured with Frequent Revivals 9 Revival of 1762-1764 10 Revivals 1765-1789 10 Revivals of the 1790s 15 Revivals of the 1800s 20 Revivals 1810-1816 24 The Beddgelert Revival 1817-1822 28 Revivals 1824-1827 32 The Carmarthenshire Revival 1828-1830 33 The Caernarfonshire Revival 1831-1833 35 Revivals 1834-1838 37 'Finney's Revival' 1839-1843 39 Revival of 1848-1850 41 Revivals 1851-1857 43 Revival of 1858-1860 44 Conclusion 45 Accounts of Revivals in Wales 1: Cardiganshire, 1762-1764 46 2: Trefeca College, Brecknockshire, 1768 47 3: Llanllyfni, Caernarfonshire, 1771-1819 47 4: Soar y Mynydd, Cardiganshire, 1779-1783 49 5: Trecastle, Brecknockshire, 1786 49 6: South Wales: Christmas Evans' preaching tour, 1791 [or 1794?] 52 7: Bala, Merionethshire, 1791-1792 53 8: Llangeitho, Cardiganshire, 1797 59 5 9: The Growth of Wesleyanism in North Wales, 1800-1803 60 10: Rhuddlan, Flintshire, 1802 63 11: Aberystwyth, Cardiganshire, 1804-1805 67 12: Bwlchygroes, Pembrokeshire, 1808 69 13: Cardiganshire, 1812 71 14: Beddgelert, Caernarfonshire, 1817-1822 72 15: Neuadd-lwyd, Cardiganshire, 1821 77 16: Anglesey, 1822 79 17: South Wales, 1828 80 18: Trelech, Carmarthenshire, 1829 83 19: Bryn-engan, Caernarfonshire, 1831 86 20: Brecon, Brecknockshire, 1836 88 21: Llanuwchllyn, Merionethshire, 1839 89 22: Henllan, Carmarthenshire, 1840 & 1850 94 23: Gaerwen, Anglesey, 1844 100 24: Caernarfonshire and Anglesey, 1848-1849 101 25: South Wales, 1849-1850 102 26:Trefeca College, 1857 and General Revival, 1858-1860 106 6 Preface Wales, the Land of Revivals, has been blessed with many periods of awakening and spiritual blessing during its history.