1 Imagebasics of Book V April 26, 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annexes Etude Sur Les Relations Entre Tf1 Et Metropole Television Et La Production Phonographique

ANNEXES ETUDE SUR LES RELATIONS ENTRE TF1 ET METROPOLE TELEVISION ET LA PRODUCTION PHONOGRAPHIQUE ANNEXE 1............................................................................................................................................... 2 LES DIVERTISSEMENTS MUSICAUX OU À COMPOSANTE MUSICALE SUR M6..................................................... 2 JUILLET ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 ANNEXE 2............................................................................................................................................. 10 LES DIVERTISSEMENTS MUSICAUX OU À COMPOSANTE MUSICALE SUR M6................................................... 10 NOVEMBRE.............................................................................................................................................. 10 ANNEXE 3............................................................................................................................................. 18 LES DIVERTISSEMENTS MUSICAUX OU À COMPOSANTE MUSICALE SUR M6................................................... 18 DÉCEMBRE .............................................................................................................................................. 18 ANNEXE 4............................................................................................................................................. 25 LES DIVERTISSEMENTS MUSICAUX OU À -

Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and McCarthy Center Student Scholarship the Common Good 2020 Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference David Donahue Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/mccarthy_stu Part of the History Commons CHANGEMAKERS AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE Biographies inspired by San Francisco’s Ella Hill Hutch Community Center murals researched, written, and edited by the University of San Francisco’s Martín-Baró Scholars and Esther Madríz Diversity Scholars CHANGEMAKERS: AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE © 2020 First edition, second printing University of San Francisco 2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117 Published with the generous support of the Walter and Elise Haas Fund, Engage San Francisco, The Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good, The University of San Francisco College of Arts and Sciences, University of San Francisco Student Housing and Residential Education The front cover features a 1992 portrait of Ella Hill Hutch, painted by Eugene E. White The Inspiration Murals were painted in 1999 by Josef Norris, curated by Leonard ‘Lefty’ Gordon and Wendy Nelder, and supported by the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Mayor’s Offi ce Neighborhood Beautifi cation Project Grateful acknowledgment is made to the many contributors who made this book possible. Please see the back pages for more acknowledgments. The opinions expressed herein represent the voices of students at the University of San Francisco and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the University or our sponsors. -

Researcher 2015;7(8)

Researcher 2015;7(8) http://www.sciencepub.net/researcher “JANGLISH” IS CHEMMOZHI?...(“RAMANUJAM LANGUAGE”) M. Arulmani, B.E.; V.R. Hema Latha, M.A., M.Sc., M. Phil. M.Arulmani, B.E. V.R.Hema Latha, M.A., M.Sc., M.Phil. (Engineer) (Biologist) [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: Presently there are thousands of languages exist across the world. “ENGLISH” is considered as dominant language of International business and global communication through influence of global media. If so who is the “linguistics Ancestor” of “ENGLISH?”...This scientific research focus that “ANGLISH” (universal language) shall be considered as the Divine and universal language originated from single origin. ANGLISH shall also be considered as Ethical language of “Devas populations” (Angel race) who lived in MARS PLANET (also called by author as EZHEM) in the early universe say 5,00,000 years ago. Janglish shall be considered as the SOUL (mother nature) of ANGLISH. [M. Arulmani, B.E.; V.R. Hema Latha, M.A., M.Sc., M. Phil. “JANGLISH” IS CHEMMOZHI?...(“RAMANUJAM LANGUAGE”). Researcher 2015;7(8):32-37]. (ISSN: 1553-9865). http://www.sciencepub.net/researcher. 7 Keywords: ENGLISH; dominant language; international business; global communication; global media; linguistics Ancestor; ANGLISH” (universal language) Presently there are thousands of languages exist and universal language originated from single origin. across the world. “ENGLISH” is considered as ANGLISH shall also be considered as Ethical dominant language of International business and global language of “Devas populations” (Angel race) who communication through influence of global media. If lived in MARS PLANET (also called by author as so who is the “linguistics Ancestor” of EZHEM) in the early universe say 5,00,000 years ago. -

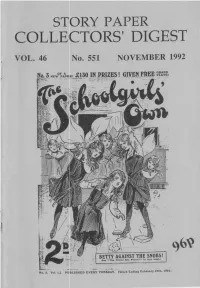

Colle1ctors' Digest

S PRY PAPER COLLE 1CTORS' DIGEST VOL. 46 No. 551 NOVEMBER 1992 BETTY AGAINST THE SNOBSI 8M u TIH Fri ... d atie ,..,,.,,d I'' II\ thi• IHllt.) - • ..a.... - No, 3, Vol . I ,) PU81. I SH£0 £VER Y TUESDAY, [Wnk End•nll f'~b,.,&ry l&th, 191 1, ONCORPORATING NORMAN SHAW) ROBIN OSBORNE, 84 BELVEDERE ROAD, LONDON SE 19 2HZ PHONE (BETWEEN 11 A.M . • 10 P.M.) 081-771 0541 Hi People, Varied selection of goodies on offer this month:- J. Many loose issues of TRIUMPH in basically very good condition (some staple rust) £3. each. 2. Round volume of TRIUMPH Jan-June 1938 £80. 3. GEM . bound volumes· all unifonn · 581. 620 (29/3 · 27.12.19) £110 621 . 646 (Jan· June 1920) £ 80 647 • 672 (July · Dec 1920) £ 80 4. 2 Volumes of MAGNET uniformly bound:- October 1938 - March 1939 £ 60 April 1939 - September 1939 £ 60 (or the pair for £100) 5. SWIFT - Vol. 7, Nos.1-53 & Vol. 5 Nos.l-52, both bound in single volumes £50 each. Many loose issues also available at £1 each - please enquire. 6. ROBIN - Vol.5, Nos. 1-52, bound in one volume £30. Many loose issues available of this title and other pre-school papers like PLA YHOUR, BIMBO, PIPPIN etc. at 50p each (substantial discounts for quantity), please enquire. 7. EAGLE - many issues of this popular paper. including some complete unbound volumes at the following rates: Vol. 1-10, £2 each, and Vol. 11 and subsequent at £1 each. Please advise requirements. 8. 2000 A.D. -

The Tolerance of English Instructors Towards the Thai-Accented English and Grammatical Errors

INDONESIAN JOURNAL OF APPLIED LINGUISTICS Vol. 9 No. 3, January 2020, pp. 685-694 Available online at: https://ejournal.upi.edu/index.php/IJAL/article/view/23219 doi: 10.17509/ijal.v9i3.23219 The tolerance of English instructors towards the Thai-accented English and grammatical errors Varisa Osatananda and Parichart Salarat* Department of English, Faculty of Liberal Arts, Thammasat University, Khlong Luang, Pathum Thani, Thailand Kasetsart University, 50 Thanon Ngamwongwan, Lat Yao, Chatuchak, Bangkok 10900, Thailand ABSTRACT Although Thai English has emerged as one variety of World Englishes (Trakulkasemsuk 2012, Saraceni 2015), it has not been enthusiastically embraced by Thai educators, as evidenced in the frustration expressed by ELT practitioners over Thai learners’ difficulties with pronunciation (Noom-ura 2013; Sahatsathatsana, 2017) as well as grammar (Saengboon 2017a). In this study, we examine the perception English instructors have on the different degrees of grammar skills and Thai-oriented English accent. We investigated the acceptability and comprehensibility of both native-Thai and native-English instructors (ten of each), as these subjects listen to controlled passages produced by 4 Thai-English bilingual speakers and another 4 native-Thai speakers. There were 3 types of passage tokens: passages with correct grammar spoken in a near-native English accent, passages with several grammatical mistakes spoken in a near-native English accent, and the last being a Thai-influenced accent with correct grammar. We hypothesized that (1) native-Thai instructors would favor the near-native English accent over correct grammar, (2) native-English instructors would be more sensitive to grammar than a foreign accent, and (3) there is a correlation between acceptability and comprehensibility judgment. -

Magazines V17N9.Qxd

June COF C1:Customer 5/10/2012 11:01 AM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 18JUN 2012 JUN E E COMIC H H T T SHOP’S CATALOG 06 JUNE COF Apparel Shirt Ad:Layout 1 5/10/2012 12:50 PM Page 1 MARVEL HEROES: “SLICES” CHARCOAL T-SHIRT Available only PREORDER NOW! from your local comic shop! GODZILLA: “GOJIRA THE OUTER LIMITS: COMMUNITY: POSTER” BLACK T-SHIRT “THE MAN “INSPECTOR SPACETIME” PREORDER NOW! FROM TOMORROW” LIGHT BLUE T-SHIRT STRIPED T-SHIRT PREORDER NOW! PREORDER NOW! COF Gem Page June:gem page v18n1.qxd 5/10/2012 9:39 AM Page 1 THE CREEP #0 MICHAEL AVON OEMING’S DARK HORSE COMICS THE VICTORIES #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BEFORE WATCHMEN: RORSCHACH #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT SUPERMAN: EARTH ONE THE ROCKETEER: VOL. 2 HC CARGO OF DOOM #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT IDW PUBLISHING IT GIRL & THE ATOMICS #1 IMAGE COMICS BLACK KISS II #1 GAMBIT #1 IMAGE COMICS MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 5/10/2012 10:54 AM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS New Crusaders: Rise of the Heroes #1 G ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Crossed: Wish You Were Here Volume 1 TP/HC G AVATAR PRESS INC Li‘l Homer #1 G BONGO COMICS Steed and Mrs Peel #0 G BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Pathfinder #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Thun‘da #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Love and Rockets Companion: 30 Years (And Counting) SC G FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Amulet Volume 5: Prince of the Elves GN G GRAPHIX 1 Amelia Rules! Volume 8: Her Permanent Record SC/HC G SIMON & SCHUSTER The Underwater Welder GN G TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Archer & Armstrong #1 G VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Tezuka‘s Message to Adolf GN G VERTICAL INC BOOKS & MAGAZINES -

Gentrification and Lesbian Subcultures in Sarah Schulman's

Aneta Dybska Gentrification and Lesbian Subcultures LQ6DUDK6FKXOPDQ¶V Girls, Visions and Everything A 2010 press release accompanying the launching of a 40-second film Discovered (Odkryta SURPRWLQJ àyGĨ DV D FDQGLGDWH IRU WKH (XURSHDQ &DSLWDO RI &XOWure 2016, GUDZVDWWHQWLRQWRWKHFLW\¶VXQLTXHQHVVDQGPDJLFDO\HWXQVHWWOLQJDSSHDO'LUHFWHGE\ %RU\V/DQNRV]³'LVFRYHUHG´LQFRUSRUDWHVWKHILOPQRLUDHVWKHWLFWRPDSWKHFLW\¶VFXl- WXUDOSRWHQWLDODQGFUHDWLYHHQHUJLHVRQWR.VLĊĪ\0á\QWKHFLW\¶VKLVWRrical textile indus- try district. Home to the thriving Polish textile industry since the early nineteenth cen- WXU\àyGĨHQWHUHGWKHWZHQW\-first century as a major player in the revitalization of its once vibrant urban spaces, including the conversion of dilapidated factory buildings in .VLĊĪ\0á\QLQWRPRGHUQOLYLQJVSDFHV$VUHFHQWO\DV0D\DQ$XVWUDOLDQFRPSa- ny, Opal Property Developments, put up for sale stylish lofts in a gated community on the former site of the Karol Scheibler factory complex. Shot against the backdrop of nineteenth-FHQWXU\ LQGXVWULDO DUFKLWHFWXUH RI ZRUNHUV¶ homes (IDPXá\), Discovered stages an urban drama of a man in a trench-coat and a felt hat, possibly a private eye, with a camera and flashlight, pursuing a woman, a femme fatale type, along the dimly-OLWDOOH\ZD\VRIQLJKWWLPH.VLĊĪ\0á\Q3OD\LQJRQWKHWUDGi- WLRQDOVH[XDODWWUDFWLRQLQWKHILOPQRLUFODVVLFV/DQNRV]IRUHJURXQGVàyGĨ¶VXUEDQP\s- WHU\LQOLQH ZLWKWKHFLW\RIILFLDOV¶SODQVWRDWWUDFWDUWLVWVLQWRWKHSRVWLQGustrial, disin- vested, city-owned area but, equally, to transform it into an incubator of creativity, thus forging a new economy of cultural production. As Lankosz admits in an interview, his inspirations take root in the experience of the American metropolis: [àyGĨ@UHPLQGVPHRI1HZ<RUNZKHUHWKHDUWLVWVVHWWKHWUHQGVLQWKHXUEDQVSDFH They get to some places first, they get the feel of those places, they are inspired by WKHP«7DNHIRUH[DPSOHWKH0HDWSDFNLQJ'LVWULFWLQ1HZ<RUN8QWLOUHFHQWO\WKLV was a EXWFKHUV¶QHLJKERUKRRGDQGWRGD\LWKDVEHFRPHDKLSSODFH7KHDUWLVWVFDPH first and attracted money to the area through fashion designers, clubs, etc. -

The Journeyers

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2014 The ourJ neyers Alyson Pomerantz Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Pomerantz, Alyson, "The ourJ neyers" (2014). LSU Master's Theses. 235. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/235 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE JOURNEYERS A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in The Department of English by Alyson Pomerantz B.A., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1998 May 2014 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………...iv Chapter 1…………………………………………………………………………………..1 Chapter 2…………………………………………………………………………………..9 Chapter 3…………………………………………………………………………………23 Chapter 4…………………………………………………………………………………30 Chapter 5…………………………………………………………………………………42 Chapter 6…………………………………………………………………………………54 Chapter 7…………………………………………………………………………………60 Chapter 8…………………………………………………………………………………66 Chapter 9…………………………………………………………………………………81 Chapter 10………………………………………………………………………………..93 -

May 15, 2019 Restaurant Guide to New York City Here Are Evaluations

May 15, 2019 Restaurant Guide to New York City Here are evaluations of restaurants that I’ve tried in New York. You’ll see that the great majority of them receive grades of A or B. I don’t think that this is because I’m an easy grader. Rather, I generally don’t go to a place unless it has received at least a 4.0 from the generally reliable Zagat guide or I’ve gotten a recommendation from a source whose judgment I trust. Still, there are clunkers now and then. Also, I grade on a curve in the sense that a great hamburger joint and a great upscale French restaurant can both merit an A+, even though the dining experiences will be rather different. (Using the jargon of economics, I’m more or less looking at the marginal utility per dollar!) For the most part, these restaurants fall in the mid-price range (for Manhattan), roughly $40 to $60 per person, without drinks. Bon appétit! Restaurant Neighborhood Date Grade Comments 33 Greenwich Greenwich October 2017 A- Southern. Updated versions of southern food were Village outstanding. Try the shrimp and grits and the meatloaf sandwich. The service, while pleasant, was too slow and inattentive. 44& ½ Hell’s Kitchen Hell’s Kitchen November 2006 B+ American. Some of the dishes were terrific (goat cheese souffle’ appetizer), but some, like the main course duck, were only ok. November 2009 A Upgraded this to an A—everything was excellent, January 2010 A service was good, and portions were substantial. October 2017 A- Everything was good. -

Mental Effort from an Lpcomin Disco Sound on This Energetic T, "MY

3, 1979 $2.25 SINGLES SLEEPERS THE WHO, "LONG LIVE ROCK" (prod. not LOUISIANA'S LE ROU listed) (writer: Peter Townshend) by L. S. Me MCA (Towser Tunes, BMI) (3:58).Ini- Pollard) RECORDStially released on their "Odds & Lemed, Sods" Ip, this comes roaring out chapter #00001"Ist "The Kids Are Alright 'sound- rock is vg trackandaptlycapturesthe one isfire theme behind one of rock's leg- blues - rock ends. MCA 41053 tempo shades.. HOT CHOCOLATE, "GOING THROUGH PHILLY CREAM, "MO THE MOTIONS" (prod by M. (prod by Barry- ri Most) (writer: E. Brown) (Finch - Barry -Ingram)(P ry serv.. ley, ASCAP) (3:54). Vocal, string BMI)(3:59).Greatead v re-mixa:] and synthesizer intensity build to trades and brilliant horns to .ontami 4a dramatic climax on this monu- disco sound on thisenergetic ostfamilsir mental effort from an Lpcomin disc. Splendid arrangement/pro- a staid -out and 1p A multi -format smash. Infinity duction give this widespread ap- the rri should 50,016. I. Fantasy/WMOT 862 110 12. THE Cane PATTI SMITH GROUP, "FREDERICK" T, "MY LOVE is" (prod by TH AR V-0. ou p CANDY -11 (prod by T. Rundigren) (writer: P t)(writers: rWright-McCray) was on andful reak Smith)(Ninja,' tASCAFT) (3:01 Iyn.BMI /DErnbet,BMI) (5:48). through t"f, dominan Smith's urgent Vocals, encas it'sfinestefforttodate summer an by ringing guitars, plead the m dikes the most of her grandiose duced by Roy Thomas sage while keyboard lines iz vocaltalentPrecision back-up tinues their esoteric roc of zle. Rundgren produces w chorals, prominent piano Imes & view. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Yiddish Songs of The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Yiddish Songs of the Shoah A Source Study Based on the Collections of Shmerke Kaczerginski A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Bret Charles Werb 2014 Copyright © Bret Charles Werb 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Yiddish Songs of the Shoah A Source Study Based on the Collections of Shmerke Kaczerginski by Bret Charles Werb Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Timothy Rice, Chair This study examines the repertoire of Yiddish-language Shoah (or Holocaust) songs prepared for publication between the years 1945 and 1949, focusing its attention on the work of the most influential individual song collector, Shmerke Kaczerginski (1908-1954). Although a number of initiatives to preserve the “sung folklore” of the Nazi ghettos and camps were undertaken soon after the end of the Second World War, Kaczerginski’s magnum opus, the anthology Lider fun di getos un lagern (Songs of the Ghettos and Camps), published in New York in 1948, remains unsurpassed to this day as a resource for research in the field of Jewish folk and popular music of the Holocaust period. ii Chapter one of the dissertation recounts Kaczerginski’s life story, from his underprivileged childhood in Vilna, Imperial Russia (present-day Vilnius, Lithuania), to his tragic early death in Argentina. It details his political, social and literary development, his wartime involvement in ghetto cultural affairs and the underground resistance, and postwar sojourn from the Soviet sphere to the West. Kaczerginski’s formative years as a politically engaged poet and songwriter are shown to have underpinned his conviction that the repertoire of salvaged Shoah songs provided unique and authentic testimony to the Jewish experience of the war. -

SOUZA, Ana Guiomar .R

MUSICOLOGIA & DIVERSIDADE Editora Appris Ltda. 1.ª Edição - Copyright© 2020 dos autores Direitos de Edição Reservados à Editora Appris Ltda. Nenhuma parte desta obra poderá ser utilizada indevidamente, sem estar de acordo com a Lei nº 9.610/98. Se incorreções forem encontradas, serão de exclusiva responsabilidade de seus organi- zadores. Foi realizado o Depósito Legal na Fundação Biblioteca Nacional, de acordo com as Leis nos 10.994, de 14/12/2004, e 12.192, de 14/01/2010. Catalogação na Fonte Elaborado por: Josefina A. S. Guedes Bibliotecária CRB 9/870 M987m Musicologia & diversidade [recurso eletrônico] / Ana Guiomar Rêgo 2020 Souza, David Cranmer, Robervaldo Linhares Rosa (organizadores). - 1. ed. – Curitiba : Appris, 2020. 1 arquivo. – (Ciências sociais. Seção história). Inclui bibliografia. ISBN 978-65-5820-197-7 1. Música – Instrução estudo. I. Souza, Ana Guiomar Rêgo. II. Cranmer, David. III. Rosa, Robervaldo Linhares. IV. Título. V. Série. CDD – 780.7 Livro de acordo com a normalização técnica da ABNT Editora e Livraria Appris Ltda. Av. Manoel Ribas, 2265 – Mercês Curitiba/PR – CEP: 80810-002 Tel. (41) 3156 - 4731 www.editoraappris.com.br Printed in Brazil Impresso no Brasil Ana Guiomar Rêgo Souza David Cranmer Robervaldo Linhares Rosa (Organizadores) MUSICOLOGIA & DIVERSIDADE FICHA TÉCNICA EDITORIAL Augusto V. de A. Coelho Marli Caetano Sara C. de Andrade Coelho COMITÊ EDITORIAL Andréa Barbosa Gouveia - UFPR Edmeire C. Pereira - UFPR Iraneide da Silva - UFC Jacques de Lima Ferreira - UP Marilda Aparecida Behrens - PUCPR ASSESSORIA