Climate Change, Natural Hazards and the Auckland Unitary Plan: Too Little Too Late?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Assessment of Areas Susceptible to Coastal Erosion Volume 2: Appendices a - J February TR 2009/009

Regional Assessment of Areas Susceptible to Coastal Erosion Volume 2: Appendices A - J February TR 2009/009 Auckland Regional Council Technical Report No. 009 February 2009 ISSN 1179-0504 (Print) ISSN 1179-0512 (Online) ISBN 978-1-877528-16-3 Contents Appendix A: Consultants Brief Appendix B: Peer reviewer’s comments Appendix C: Summary of Relevant Tonkin & Taylor Jobs Appendix D: Summary of Shoreline Characterization Appendix E: Field Investigation Data Appendix F: Summary of Regional Beach Properties Appendix G: Summary of Regional Cliff Properties Appendix H: Description of Physical Setting Appendix I: Heli-Survey DVDs (Contact ARC Librarian) Appendix J: Analysis of Beach Profile Changes Regional Assessment of Areas Susceptible to Coastal Erosion, Volume 2: Appendices A-J Appendix A: Consultants Brief Appendix B: Peer reviewer’s comments Appendix C: Summary of relevant Tonkin & Taylor jobs Job Number North East Year of Weathered Depth is Weathered Typical Cliff Cliff Slope Cliff Slope Composite Composite Final Slope Geology Rec Setback erosion rate Comments Street address Suburb investigation layer depth Estimated/ layer Slope weathered layer Height (deg) (rads) slope from slope from (degree) from Crest (m) (m/yr) (m) Greater than (deg) slope (rad) (m) calc (degree) profile (deg) 6 RIVERVIEW PANMURE 12531.000 2676066 6475685 1994 2.40 58 0.454 12.0 51.5 0.899 43.70 35 35 avt 6 ROAD 15590.000 6472865 2675315 2001 2.40 0.454 4.0 30.0 0.524 27.48 27 avt 8 29 MATAROA RD OTAHUHU 16619.000 6475823 2675659 1999 2.40 0.454 6.0 50.0 0.873 37.07 37 avt LAGOON DRIVE PANMURE long term recession ~ FIDELIS AVENUE 5890.000 2665773 6529758 1983 0.75 G 0.454 0.000 N.D Kk 15 - 20 0.050 50mm/yr 80m setback from toe FIDELIS AVE ALGIES BAY recc. -

2014 Alternative Port Location Investigation

Ports of Auckland Limited Topic 005 - RPS Issues Submitter number 5137 Primary evidence IN THE MATTER of the Resource Management Act 1991 and the Local Government (Auckland Transitional Provisions) Act 2010 AND IN THE MATTER of the Proposed Auckland Unitary Plan STATEMENT OF EVIDENCE OF STEPHEN JOHN PRIESTLEY FOR PORTS OF AUCKLAND LIMITED IN RELATION TO TOPIC 005 - RPS ISSUES ALTERNATIVE PORT INVESTIGATION 17 OCTOBER 2014 D A Nolan / S H Pilkinton Phone +64 9 367 8000 Fax +64 9 367 8163 PO Box 8 DX CX10085 Auckland 1140 Ports of Auckland Limited Topic 005 - RPS Issues Submitter number 5137 Primary evidence Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 1 2. CONSTRAINTS MAP ................................................................................. 3 3. ALTERNATIVE CONCEPT DESIGNS ........................................................ 7 4. CONSENTABILITY AND ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS .......................... 12 5. CONCLUSION ......................................................................................... 16 2799998 i Ports of Auckland Limited Topic 005 - RPS Issues Submitter number 5137 Primary evidence EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A. POAL has commissioned an independent investigation into alternative locations for an Auckland port. The investigation has been prepared in part to inform decision making on submissions on the Proposed Auckland Unitary Plan that seek that the Port of Auckland be relocated or an alternative location be considered. In this evidence, I summarise -

Meet Your Franklin Local Board Candidates P4-5

6 September 2019 Issue 1317 Stephanie McLean –Harcourts Pohutukawa Coast Stephanie Mclean Licensed Agent REAA 2008. Election Sales &Marketing Specialist M 021 164 5111 Hoverd&Co. SPeCIAL special AGENTs IAN 0272859314 JENNY02040002564 Meet your NICOLETTE0277029157 Franklin Local Board candidates TING 40 p4-5 RA Y B T E E OR ON A R L MTIMBER E CO.LTD S C 292 8656 • • 19 9 79 – 201 Morton Timber Co. Ltd 226 NorthRoad, Clevedon2248 Ph 292 8656 or 021943 220 Email: [email protected] Web: www.mortontimber.co.nz Like us on Facebook to go in the draw to WIN a$150 voucher fordinneratyour INSIDE: AT proposes road repairs p2 Urban East feature p6-7 Sports news p10-11 favouritelocal restaurant GetaJumponthe Spring Market... Call EliseObern Great Smiles. P:(09) 536 7011 or (021) 182 5939 Better Health. E:[email protected] W: rwbeachlands.co.nz At Anthony Hunt Dental we have been A:81Second View Avenue, Beachlands East Tamaki proud to be serving our local community since 2011. Creating great smiles and FREE PROPERTY APPRAISAL AND better health for the whole family. MARKET UPDATE AVAILABLE NOW! Uniforms&Promotional Products FollowusonFacebook andInstagram Ray White Beachlands (09) 292 9071 [email protected] Lighthouse Real Estate Limited for specials, competitionsand giveaways 52 Papakura-Clevedon Road Licensed (REAA 2008) Cnr Smales and Springs Rds,EastTamaki-09 265 0300 www.ahdental.co.nz DEADLINES: Display advertising - 5pm Friday. Classifieds and News - midday Monday Ph: 536 5715 Email: [email protected] www.pctimes.nz 2 POHUTUKAWA COAST TIMES (6 September 2019) Guest editorial by Orere Community and Boating Association committee member Tim Greene GET IN TOUCH P: 536 5715 The last few years has seen the resi- scheme. -

Rapid, Cost-Effective 3D Monitoring of Urban Landslide Displacements Using UAV-Structure from Motion (Sfm) (3714483)

Final-Reporting-2 Title of research (EQC grant reference number): Rapid, cost-effective 3D monitoring of urban landslide displacements using UAV-Structure from Motion (SfM) (3714483) Principal Investigator/s, Organisation/s: Martin Brook, Jon Tunnicliffe, University of Auckland Research team: University of Auckland students Jesse Merkle, Vivek Vaidya and Kathryn Ryder undertook fieldwork and data modelling; technician Brendan Hall assisted with UAV data acquisition Ross Roberts (Auckland Council) provided conceptual ideas and advice at the start of this project Key words Landslide; structure-from-motion; slope stability; Auckland Summary The undulating topography of the Auckland urban region is susceptible to landslides of varying process-mechanisms, including: (1) earthflows of saturated Pleistocene Tauranga Group sediments, tephra and residual soils flowing off more competent underlying rock; (2) rotational slumping of man-made fill or Tauranga Group sediments; (3) block- slides of weak Miocene Waitemata Group sedimentary rock, dipping out of slope. Such landslides are often triggered by intense short periods, or prolonged periods of rainfall, such as the ‘Tasman Tempest’ and ex-Tropical Cyclone Debbie storms of 2017. Typically, rainfall infiltration results in a rise of the groundwater table and an increase of the pore water pressure, causing a reduction in effective normal stress and thereby soil strength, leading to landslides. Such landslide risk is likely to be accentuated in the Auckland region in future given the projected population growth and planned urban and commercial expansion driving the Auckland Unitary Plan (AUP). Indeed, the AUP encourages greater intensification by rezoning many areas to allow construction of low-rise apartments. Therefore, monitoring slope stability in the Auckland region is important, and requires assessment of the extent, rate of displacement, surface topography, and detection of tension cracks developing from slope deformation. -

Part 2 the City: Present and Future Trends

• PART 2 - CONTENTS PART 2 THE CITY: PRESENT AND FUTURE TRENDS 2. 1 THE FORM OF THE CITY 2.2 GROWTH OF THE CITY 2.3 ETHNIC ORIGIN OF POPULATION 2.4 EMPLOYMENT 2.5 BUILDING DEVELOPMENT AND DEMAND 2.6 TRANSPORTATION AND LAND USE 2.7 FUTURE URBAN GROWTH 2.8 LAND PRESENTLY ZONED FOR URBAN USES 2.9 RURAL LAND USE 2.10 CONTEXT OF THE PLANNING SCHEME CITY OF MANUKAU SECOND REVIEW PART 2 - THE CITY: PRESENT AND FUTURE TRENDS 2.1 THE FORM OF THE CITY Manukau City had a population in March 1986 of 177,248. Its land area of over 600 square kilometres dominates the southern part of the Auckland Region. The territorial integrity of the district, stretches from the edge of the Auckland isthmus in the north to the Hunua Ranges in the south. The Manukau City Centre, 25 km south of Auckland Centre, is the natural geographical focus of the city's urban area. When fully developed the urban area will stretch out from the Centre southwards to Manurewa, northeastwards to Otara and Pakuranga and northwest to Mangere. Two-thirds of the City's land area is in rural use, ranging from dairy and town milk supply units to pastoral farming, horticulture and forestry. A distinctive feature of the district is its extensive coastline of 320 km. In the west is the Manukau Harbour, from which the City takes its name. In the east is the Hauraki Gulf and in the north the Tamaki River. Residential development in the urban part of the City has taken full advantage of the coastline. -

Hunua Trail: Visitor Amenities Analysis

Hunua Trail: Visitor Amenities Analysis The New Zealand Tourism September 2018 Research Institute Table of contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 The audit approach .......................................................................................................... 5 Visitor Amenities Analysis ................................................................................................ 6 Database and map of visitor amenities ................................................................................. 6 Web Audit ............................................................................................................................ 12 Wikipedia ......................................................................................................................... 12 Visibility on national tourism portals ............................................................................... 12 Regional level – Auckland ................................................................................................ 13 Local level ......................................................................................................................... 13 Social media ..................................................................................................................... 14 Summary .......................................................................................................................... 14 On-site experience -

Vulnerability and Adaptation to Sea-Level Rise in Auckland, New Zealand

Vulnerability and adaptation to sea-level rise in Auckland, New Zealand Georgina Hart NZCCRI 2011 report 08 October 2011 The New Zealand Climate Change Research Institute Victoria University of Wellington The New Zealand Climate Change Research Institute School of Geography, Environment and Earth Sciences Victoria University of Wellington PO Box 600 Wellington New Zealand Contact: Liz Thomas Phone: (04) 463 5507 Email: [email protected] Acknowledgements This research was funded by the Foundation for Research, Science and Technology under contract VICX0805 Community Vulnerability and Resilience. The research was conducted as a Masters of Environmental Studies supervised by Associate Professor Ralph Chapman of the School of Geography, Environment and Earth Sciences at Victoria University of Wellington, and Dr Andy Reisinger at the New Zealand Climate Change Research Institute, Victoria University of Wellington (CCRI) now at the New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre. Ongoing support and review was provided by Judy Lawrence, Adjunct Research Associate (CCRI). Simon Tegg and Dorothee Quade, research assistants at CCRI, contributed to this document. Professor Martin Manning (CCRI), as research programme leader, provided invaluable support and reviewed the draft of this report along with Ann Magee (previously Auckland Regional Council) for which the researcher is very grateful. Inundation modelling was conducted by Doug Ramsay, Rob Bell, and colleagues at the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA), and initial GIS analysis was conducted by Scott Schimmel (Victoria University of Wellington) Auckland Regional Council. Auckland and Manukau city councils provided ongoing input and support, including GIS data and data licences for inundation modelling. The researcher would also like to sincerely thank the interview participants whose input was crucial to this research. -

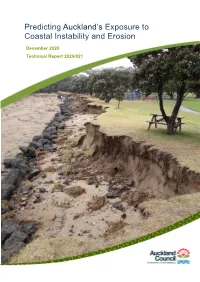

Predicting Auckland's Exposure to Coastal Instability and Erosion

Predicting Auckland’s Exposure to Coastal Instability and Erosion December 2020 Technical Report 2020/021 Cover picture: Stanmore Bay PREDICTING AUCKLAND’S EXPOSURE TO COASTAL INSTABILITY AND EROSION Predicting Auckland’s exposure to coastal instability and erosion, TR2020/021 December 2020 Auckland Council ISSN 2230-4525 (Print) ISSN 2230-4533 (Online) ISBN 978-1-99-002266-1 (Print) ISBN 978-1-99-002267-8 (PDF) Reviewed and recommended for publication by: Name: Branko Veljanovski Position: Head of Engineering Design & Asset Management Approved for publication by: Name: Sarah Sinclair Position: Chief Engineer Recommended citation: Roberts, R., N Carpenter and P Klinac (2020). Predicting Auckland’s exposure to coastal instability and erosion, Auckland Council, technical report, TR2020/021 © 2020 Auckland Council Auckland Council disclaims any liability whatsoever in connection with any action taken in reliance of this document for any error, deficiency, flaw or omission contained in it. This document is licensed for re-use under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. In summary, you are free to copy, distribute and adapt the material, as long as you attribute it to Auckland Council and abide by the other licence terms. PREDICTING AUCKLAND’S EXPOSURE TO COASTAL INSTABILITY AND EROSION Acknowledgements This document was prepared with technical input from Auckland Council and industry experts including, but not limited to, the following individuals: Authors (Part 1) Natasha Carpenter, Ross Roberts, Paul Klinac (Auckland -

Clevedon Roundup

Photo: Winter’s morning in Clevedon CLEVEDON ROUNDUP YOUR COMMUNITY INFORMATION NEWSPAPER No. 384 July-August 2018 IT’S AG DAY TIME! It’s that time of year when one of our points of difference is highlighted in ROUNDUP PAGE INDEX Clevedon. It’s great to see our children still interacting with nature, being taught Friends of Hunua Ranges 3 responsibility and even having fun taking their lambs for walks down the main Daffodil Day 3 street. Hats off to the parents for their commitment too! Advertising rates 4 Important Dates 4 Owners of orphaned animals can easily find willing families on Facebook Clevedon Protection Soc. 5 Clevedon/Kawakawa Bay grapevine, or contact your local school. There are Local Council news 6 different restrictions on birth dates etc, for example at Clevedon School; lambs, Clevedon CBA 7 kids & chickens must be born between 1/6/18 and 27/7/18 and calves will not be Clevedon Conversations 7 allowed this year due to mycoplasma bovis unfortunately. Snippets 8 So for our younger readers, check out your school guidelines and enjoy! Early Clevedon Families 10 Ag Day for Clevedon School is 21 September, for Brookby School it’s 23 MP Andrew Bayly 11 September, for Ardmore School it’s 26 September, and for Hunua School it’s 27 Clevedon Valley Music 11 October. Clevedon Cares 13 Clevedon Plunket 13 Anglican Church 15 Clevedon Lions 16 Friends of Te Wairoa 19-20 Presbyterian Church 21 Club News 22-23 Community Notices 24 Local trades & businesses 2, 9, 12, 14, 17, 18 1 LOCAL TRADE & BUSINESS Accounting Services in Clevedon Financial Accounts Tax & GST Returns Business & Personal Tax Advice 37 Papakura Clevedon Road Ph 2929470 www.myersca.co.nz 2 Supporting and assisting Sign Up for our e-mail newsletter at the protection and use of www.friendsofhunuaranges.co.nz the unique Hunua Ranges Contact Us Ph: Mary 021614499 New supporters welcome! Pest Eradication – 1080 There will be an aerial application of 1080 in the Hunua forest in late Winter /Spring depending on the weather. -

Submissions on the Draft Regional Land Transport Plan 2021-2031

Submissions on the Draft Regional Land Transport Plan 2021-2031 from local boards, partners and key interest groups Contents Part A – Local Board submissions on the RLTP .............................................................. 1 Albert-Eden Local Board ................................................................................................... 2 Aotea-Great Barrier Local Board ....................................................................................... 6 Devonport-Takapuna Local Board ..................................................................................... 8 Franklin Local Board ........................................................................................................ 14 Henderson-Massey Local Board ...................................................................................... 20 Hibiscus and Bays Local Board ....................................................................................... 25 Howick Local Board ......................................................................................................... 28 Kaipātiki Local Board ....................................................................................................... 30 Māngere-Ōtāhuhu Local Board ....................................................................................... 35 Manurewa Local Board .................................................................................................... 43 Maungakiekie-Tāmaki Local Board ................................................................................. -

Kawakawa Bay's New Mascot Helps Owner Meet Community

Please support the businesses who support your local paper! 27 March 2020 Issue 1341 Kawakawa Bay’s new mascot helps owner meet community ‘Boy’ the Houdini pig has become something of a media sensation over the past few weeks, after taking it upon himself to become acquainted with Kawakawa Bay residents. The one-year-old kunekune enjoys wandering from his waters-edge home down to the bay in search of company, a scratch, and hopefully some food scraps. Boy’s owner, Graeme Kepa, says that while he does his best to keep Boy well-fed, pigs will be pigs. “He never gets full, he’s always looking for more food.” Boy is a big fan of the ladies. “As soon as he hears a ladies’ voice, he heads straight for them.” Through Boy’s escapades, Graeme Attention Landlords: has got to meet more people within Time to Call the community - and he is keen for Richel Barlow this to continue. P:(09) 536 7011 or (021) 433 052 “I want people to be involved with E:[email protected] Boy - if you have food scraps going W: rwbeachlands.co.nz A:81 Second View Avenue, to waste, Boy would love them. I Beachlands know people lead busy lives, so I’m happy to drop off buckets that Ray White Beachlands Lighthouse Real Estate Limited people can fill with household Licensed (REAA 2008) scraps. I can pick them up, or I’m really happy for people to drop the scraps off to my place and give Boy Laminata Horizontal Fencing a scratch.