Whitman's Compost

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Charris Efthimiou Metallica's Tone Colour Characteristics of Their Riffs

Charris Efthimiou Metallica’s Tone Colour Characteristics of their Riffs (1983–1986) and the Differences between Slayer and the New Wave of British Heavy Metal Annotation The aim of this article is to consider the design of the riffs of Angel of Death and other songs from the first three albums by Slayer (Show No Mercy 1983, Hell Awaits 1985 and Reign in Blood 1986) from a music analytical point of view (including tone-colour analysis of the riffs). If Slayer’s riff design (from 1983 to 1986) is considered from an overall perspective, the following results can be observed: • A rapid tempo and a constant change in the tone-colours of the guitar (palm mute, powerchords and monophonic melodies) characterise the sound of most riffs from the first three albums of this band. • Although the number of tone colours is limited, exact repetitions of tone colours are avoided. • Melodies in thirds, sixths and octaves are rare. At the same time (1983–1986) and in the same geographic area (U.S. West Coast), the band Metallica found their own compositional path within the thrash metal genre. Although the two bands dedicate their songs to very different topics, there are significant proximity points in the section of riff design. The same music-analytical methods (such as the analysis of tone- colours) are used with Metallica again. Thus, on the one hand, correlations can be determined and special features unique with Slayer’s music can be highlighted on the other. Furthermore, in order to determine other similarities and differences, the riffs of Metallica and Slayer will be compared with riffs by bands belonging to the NWoBHM (New Wave of British Heavy Metal) and were active in the years 1983–1986 (including Iron Maiden and Motörhead). -

Cassettes an Affordable Analog Companion to Vinyl BANDCAMP OPTIMIZATIONS RECORDING

FREE FOR MUSICIANS details inside GETTING THINGS DONE IN HEAVY UNDERGROUND MUSIC • AUGUST 2020 Cassettes An affordable analog companion to vinyl BANDCAMP OPTIMIZATIONS RECORDING .................. APART 9 Improve your store forever in an hour Advice for collaborating on sessions when you can’t be in the same room Interviews with: CHRISTINE KELLY DOOMSTRESS ALEXIS HOLLADA Owner of Tridroid Records Singer, songwriter, bassist, band leader EARSPLIT PR DAN KLEIN New York veterans delivering Producer at Iron Hand Audio, exposure to the masses drummer for FIN, Berator & more DAVID PAUL SEYMOUR VITO MARCHESE Illustrator of doom Novembers Doom, The Kahless Clone, Resistance HQ Publishing VOL. 1, ISSUE 1. THERE WILL BE TYPOS, WE GUARANTEE IT. 4 Vito Marchese 8 Earsplit PR Free print subscriptions 12 Cassettes for US musicians. 18 Doomstress Alexis Hollada Subscribe online at 22 Dan Klein WorkhorseMag.com (or just email us) 27 Christine Kelly 30 David Paul Seymour 34 Bandcamp Optimizations Workhorse Magazine Harvester Publishing LLC, 37 Recording.............apart www.workhorsemag.com PO Box 322, Hutto TX 78634 [email protected] 38 Publisher Notes [email protected] Cover art by David Paul Seymour The tiny, USA made condenser microphone, making a big sound on countless hits. "I think the first thing I threw it on was my guitar amp and I remember being blown away, honestly. The sound was so big and the sonic spectrum felt so broad and open, yet focused." - Teppei Teranishi (Thrice) L I T T L E B L O N D I E M I C R O P H O N E S Exclusive offer! Save 15% with coupon code: Workhorse Buy now on LittleBlondie.com Photo by Hillarie Jason, taken at Prophecy Fest 2018 Vito Marchese Chicago guitarist on his work with Novembers Doom, The Kahless Clone and his tablature publishing company, Resistance HQ Publishing. -

Mysticism, Implicit Religion and Gravetemple's Drone Metal By

1 The Invocation at Tilburg: Mysticism, Implicit Religion and Gravetemple’s Drone Metal by Owen Coggins 1.1 On 18th April 2013, an extremely slow, loud and noisy “drone metal” band Gravetemple perform at the Roadburn heavy metal and psychedelic rock festival in Tilburg in the Netherlands. After forty-five minutes of gradually intensifying, largely improvised droning noise, the band reach the end of their set. Guitarist Stephen O’Malley conjures distorted chords, controlled by a bank of effects pedals; vocalist Attila Csihar, famous for his time as singer for notorious and controversial black metal band Mayhem, ritualistically intones invented syllables that echo monastic chants; experimental musician Oren Ambarchi extracts strange sounds from his own looped guitar before moving to a drumkit to propel a scattered, urgent rhythm. Momentum overtaking him, a drumstick slips from Ambarchi’s hand, he breaks free of the drum kit, grabs for a beater, turns, and smashes the gong at the centre of the stage. For two long seconds the all-encompassing rumble that has amassed throughout the performance drones on with a kind of relentless inertia, still without a sonic acknowledgement of the visual climax. Finally, the pulsating wave from the heavily amplified gong reverberates through the corporate body of the audience, felt in physical vibration more than heard as sound. The musicians leave the stage, their abandoned instruments still expelling squalling sounds which gradually begin to dissipate. Listeners breathe out, perhaps open their eyes, raise their heads, shift their feet and awaken enough to clap and shout appreciation, before turning to friends or strangers, reaching for phrases and gestures, often in a vocabulary of ritual, mysticism and transcendence, which might become touchstones for recollection and communication of their individual and shared experience. -

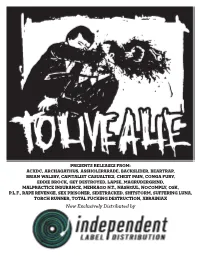

Now Exclusively Distributed by ACXDC Street Date: He Had It Coming, 7˝ AVAILABLE NOW!

PRESENTS RELEASES FROM: ACXDC, ARCHAGATHUS, ASSHOLEPARADE, BACKSLIDER, BEARTRAP, BRIAN WALSBY, CAPITALIST CASUALTIES, CHEST PAIN, CONGA FURY, EDDIE BROCK, GET DESTROYED, LAPSE, MAGRUDERGRIND, MALPRACTICE INSURANCE, MEHKAGO N.T., NASHGUL, NOCOMPLY, OSK, P.L.F., RAPE REVENGE, SEX PRISONER, SIDETRACKED, SHITSTORM, SUFFERING LUNA, TORCH RUNNER, TOTAL FUCKING DESTRUCTION, XBRAINIAX Now Exclusively Distributed by ACXDC Street Date: He Had It Coming, 7˝ AVAILABLE NOW! INFORMATION: Artist Hometown: Los Angeles, CA Key Markets: LA & CA, Texas, Arizona, DC, Baltimore MD, New York, Canada, Germany For Fans of: MAGRUDERGRIND, NASUM, NAPALM DEATH, DESPISE YOU ANTI-CHRIST DEMON CORE’s He Had it Coming repress features the original six song EP released in 2005 plus two tracks from the same session off the A Sign Of Impending Doom Compilation. The band formed in 2003, recorded these songs in 2005 and then vanished for awhile on a many- year hiatus, only to resurface and record and release a brilliant new EP and begin touring again in 2011/2012. The original EP is long sought after ARTIST: ACXDC by grindcore and powerviolence fiends around the country and this is your TITLE: He Had It Coming chance to grab the limited repress. LABEL: TO LIVE A LIE CAT#: TLAL64AB Marketing Points: FORMAT: 7˝ GENRE: Grindcore • Hugely Popular Band BOX LOT: NA • Repress of Long Sold Out EP SRLP: $5.48 • Huge Seller UPC: 616983334836 • Two Extra Songs In Additional To Originals EXPORT: NO RESTRICTIONS • Two Bonus Songs Never Before Pressed To Vinyl, In Additional To Originals Tracklist: 1. Dumb N Dumbshit 2. Death Spare Not The Tiger 3. Anti-Christ Demon Core 4. -

Hipster Black Metal?

Hipster Black Metal? Deafheaven’s Sunbather and the Evolution of an (Un) popular Genre Paola Ferrero A couple of months ago a guy walks into a bar in Brooklyn and strikes up a conversation with the bartenders about heavy metal. The guy happens to mention that Deafheaven, an up-and-coming American black metal (BM) band, is going to perform at Saint Vitus, the local metal concert venue, in a couple of weeks. The bartenders immediately become confrontational, denying Deafheaven the BM ‘label of authenticity’: the band, according to them, plays ‘hipster metal’ and their singer, George Clarke, clearly sports a hipster hairstyle. Good thing they probably did not know who they were talking to: the ‘guy’ in our story is, in fact, Jonah Bayer, a contributor to Noisey, the music magazine of Vice, considered to be one of the bastions of hipster online culture. The product of that conversation, a piece entitled ‘Why are black metal fans such elitist assholes?’ was almost certainly intended as a humorous nod to the ongoing debate, generated mainly by music webzines and their readers, over Deafheaven’s inclusion in the BM canon. The article features a promo picture of the band, two young, clean- shaven guys, wearing indistinct clothing, with short haircuts and mild, neutral facial expressions, their faces made to look like they were ironically wearing black and white make up, the typical ‘corpse-paint’ of traditional, early BM. It certainly did not help that Bayer also included a picture of Inquisition, a historical BM band from Colombia formed in the early 1990s, and ridiculed their corpse-paint and black cloaks attire with the following caption: ‘Here’s what you’re defending, black metal purists. -

Best Music World Gmbh Tel.: +49 251 28099000 Fax: +49 251 28099001 Vorbestellungs Tipp`S Mailto : [email protected] Freitag, 24

Am Knapp 2 D-48159 Münster Best Music World GmbH Tel.: +49 251 28099000 Fax: +49 251 28099001 Vorbestellungs Tipp`s mailto : [email protected] Freitag, 24. September 2021 17.09.2021 24.09.2021 CD CARCASS TORN ARTERIES (CD DIGIP 13,99 € CD AERZTE DIE DUNKEL (IM SCHUBER MIT Im Schuber + Girlande 17,99 € Offer! DIE DREI ??? 212/DER WEISSE LEOPARD 6,50 € ANGELS & AIRWAVES LIFEFORMS 10,99 € Offer! DYLAN BOB SPRINGSTIME IN NEW YOR 2CD 14,99 € IMBRUGLIA NATALIE FIREBIRD 10,99 € Offer! GENESIS THE LAST DOMINO (LTD. 2C Ltd. 2CD 13,99 € Offer! PETRY WOLFGANG AUF DAS LEBEN 12,99 € Offer! MAFFAY PETER SO WEIT 12,99 € Offer! VAR KUSCHELROCK 35 15,99 € Offer! MUTZKE MAX WUNSCHLOS SUECHTIG 13,99 € LP AERZTE DIE DUNKEL (LTD. COLORED 2L Ltd. Colored 2LP im Schub 37,50 € Offer! POISEL PHILIPP NEON (CD GATEFOLD) 13,99 € ANGELS & AIRWAVES LIFEFORMS (MAGENTA MIN Ltd. Colored 18,99 € Offer! RAGE RESURRECTION DAY 11,99 € BLACK SABBATH SABBATH BLOODY SABBAT Ltd. Splattered 17,99 € Offer! SILLY INSTANDBESETZT 12,99 € Offer! CLARK ANNE JOINED UP WRITING (VINYL 15,99 € Offer! SPIRITBOX ETERNAL BLUE 10,99 € Offer! DIE DREI ??? 212/DER WEISSE LEOPARD 2LP 13,99 € Offer! VAR VOLKSMUSIK HITS 2021 (2C 2CD + DVD 13,99 € Offer! DORO WARLOCK-TRIUMPH...LIVE ( Black/White Colored 16,99 € Offer! VAR SCHLAGER HITS 2021 (3CD 3CD + DVD 15,99 € Offer! FLYING LOTUS YASUKE (LTD. RED COLORE Ltd. Red Colored 16,99 € WOOD RONNIE & THE MR.LUCK-A TRIBUTE TO JIM 11,99 € Offer! HELLOWEEN PINK BUBBLES GO APE (30T Ltd. -

The Devil's Music

religions Article The Devil’s Music: Satanism and Christian Rhetoric in the Lyrics of the Swedish Heavy Metal Band Ghost P.C.J.M. (Jarell) Paulissen Department of Biblical Sciences and Church History, Tilburg School of Catholic Theology, P.O. Box 90153, 5000 LE Tilburg, The Netherlands; [email protected] Abstract: This paper is an inquiry into a contemporary heavy metal band from Sweden called Ghost. Ghost released its first studio album in 2010 and, while there is some discussion as to what their genre is exactly, they immediately became a rising star in the metal scene. Yet what is of particular interest from a storytelling point of view, especially with regard to theological answers to philosophical questions in popular culture, is that the band presents itself as a satanic version of the Catholic Church through their stage act and lyrics. This made me curious whether they are trying to convey a message and, if yes, what that message might be. For the present paper, I have focused on the latter by performing a non-exhaustive textual analysis of the lyrics in a selection of songs from each of the four studio albums released so far. Ghost turns Christian liturgy on its head by utilizing devout language that is normally reserved for God and Christ to describe Satan and the Antichrist, a strategy I have called the ”satanification” of Christian doctrine, and in doing so their songs evoke imagery of a satanic faith community at prayer. The band then uses this radical inversion of traditional Christian themes to criticize certain elements of society, especially those aspects they associate with organized religion. -

17-06-27 Full Stock List Drone

DRONE RECORDS FULL STOCK LIST - JUNE 2017 (FALLEN) BLACK DEER Requiem (CD-EP, 2008, Latitudes GMT 0:15, €10.5) *AR (RICHARD SKELTON & AUTUMN RICHARDSON) Wolf Notes (LP, 2011, Type Records TYPE093V, €16.5) 1000SCHOEN Yoshiwara (do-CD, 2011, Nitkie label patch seven, €17) Amish Glamour (do-CD, 2012, Nitkie Records Patch ten, €17) 1000SCHOEN / AB INTRA Untitled (do-CD, 2014, Zoharum ZOHAR 070-2, €15.5) 15 DEGREES BELOW ZERO Under a Morphine Sky (CD, 2007, Force of Nature FON07, €8) Between Checks and Artillery. Between Work and Image (10inch, 2007, Angle Records A.R.10.03, €10) Morphine Dawn (maxi-CD, 2004, Crunch Pod CRUNCH 32, €7) 21 GRAMMS Water-Membrane (CD, 2012, Greytone grey009, €12) 23 SKIDOO Seven Songs (do-LP, 2012, LTM Publishing LTMLP 2528, €29.5) 2:13 PM Anus Dei (CD, 2012, 213Records 213cd07, €10) 2KILOS & MORE 9,21 (mCD-R, 2006, Taalem alm 37, €5) 8floors lower (CD, 2007, Jeans Records 04, €13) 3/4HADBEENELIMINATED Theology (CD, 2007, Soleilmoon Recordings SOL 148, €19.5) Oblivion (CD, 2010, Die Schachtel DSZeit11, €14) Speak to me (LP, 2016, Black Truffle BT023, €17.5) 300 BASSES Sei Ritornelli (CD, 2012, Potlatch P212, €15) 400 LONELY THINGS same (LP, 2003, Bronsonunlimited BRO 000 LP, €12) 5IVE Hesperus (CD, 2008, Tortuga TR-037, €16) 5UU'S Crisis in Clay (CD, 1997, ReR Megacorp ReR 5uu2, €14) Hunger's Teeth (CD, 1994, ReR Megacorp ReR 5uu1, €14) 7JK (SIEBEN & JOB KARMA) Anthems Flesh (CD, 2012, Redroom Records REDROOM 010 CD , €13) 87 CENTRAL Formation (CD, 2003, Staalplaat STCD 187, €8) @C 0° - 100° (CD, 2010, Monochrome -

Slayer Seasons in the Abyss Album Download

Slayer seasons in the abyss album download 10 - Spill the Blood DOWNLOAD FULL ALBUM 7. SLAYER - SEASON IN THE ABYSS 01 - War Ensemble 02 - Blood Red 03 - Spirit In Black. War Ensemble Red In Black able Youth Skin Mask ed Point ons of Society. Download MP3 Songs Free Online Slayer seasons in the abyss 3 MP3 youtube downloader music free download - Search for your favorite music and. Watch the video, get the download or listen to Slayer – Seasons In The Abyss for free. Seasons In The Abyss appears on the album Seasons in the Abyss. Dead Skin Mask ed Point ons of Society tion of Fire. Slayer - Seasons In The Abyss Album Download. Download Selected Tracks. MP3 - HQ; MP3 - MQ; MP3 - LQ. Online player is only for users. Please login. Seasons In The Abyss by Slayer. Album Credits and Album Name, Length, Format, Sample Rate, Price Which Format Should I Download? Comments Off on Slayer – Seasons In The Abyss (/) Studio Master, Official Digital Download – Source: | @ Def Jam of Reign in Blood for their third major-label album, Seasons in the Abyss. SLAYER SEASONS IN THE ABYSS FULL ALBUM MP3 Download ( MB), Video 3gp & mp4. List download link Lagu MP3 SLAYER SEASONS IN THE. Slayer playing at Download Festival Buy Seasons In The Abyss: Read Digital Music Reviews - Start your day free trial of Unlimited to listen to this album plus tens of millions more songs. Exclusive Prime .. You cannot download to add to your collection. A follow-up album to South Of Heaven, Seasons in the Abyss, was more of a return to the sound of Stream Seasons In The Abyss by Slayer and tens of millions of other songs on all your . -

Green Is the New Black (Metal): Wolves in the Throne Room, Die Amerikanische Romantik Und Ecocriticism 2012

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Sascha Pöhlmann Green is the New Black (Metal): Wolves in the Throne Room, die amerikanische Romantik und Ecocriticism 2012 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/3771 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Pöhlmann, Sascha: Green is the New Black (Metal): Wolves in the Throne Room, die amerikanische Romantik und Ecocriticism. In: Rolf F. Nohr, Herbert Schwaab (Hg.): Metal Matters. Heavy Metal als Kultur und Welt. Münster: LIT 2012 (Medien'Welten 16), S. 263–277. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/3771. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Weitergabe unter Attribution - Non Commercial - Share Alike 3.0/ License. For more gleichen Bedingungen 3.0/ Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere information see: Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Sascha Pöhlmann Green is the New Black (Metal): Wolves in the Throne Room, die amerikanische Romantik und Ecocriticism Wolves in the Throne Room und die transzendentalistische Konstante Im Jahr 1820 stellte der englische Publizist Sydney Smith eine berühmte Frage zur bisherigen amerikanischen Kulturleistung: »In the four quarters of the glo- be, who reads an American book?« (1820, 79). Diese Frage hat sich längst erle- digt, aber fast 200 Jahre später kann man parallel dazu andere Bereiche kul- tureller Produktion betrachten und fragen: Wer an den vier Enden der Erde hört amerikanischen Black Metal? Das Genre scheint fest in Europa verwurzelt, und auch wenn Black Metal global gespielt und gehört wird, waren US-ameri- kanische Bands bisher eher Randerscheinungen; dies änderte sich spätestens 2007 mit der vielbeachteten Veröffentlichung von Two Hunters, dem zwei- ten Album von Wolves in the Throne Room. -

La Nouvelle Adresse Performances, Musiques Et Paroles Live Œuvres in Situ, Cinéma

La nouvelle adresse Performances, musiques et paroles live œuvres in situ, cinéma Centre national des arts plastiques 1. Communiqué de presse 5 2. Programme détaillé 7 Vendredi 14 septembre 7 Samedi 15 septembre 7 Dimanche 16 septembre 8 Tout le week-end 8 3. Artistes et œuvres présentés 9 En permanence 9 Vendredi 14 septembre 11 Samedi 15 septembre 12 Dimanche 16 septembre 13 4. 81, rue Cartier-Bresson 15 5. Présentation du Cnap 16 6. Partenaires de La nouvelle adresse 17 Partenaires institutionnels 17 Partenaires médias 17 Autre partenaire 18 7. Visuels disponibles pour la presse 19 8. Informations pratiques 24 Communiqué 1. de presse Visite presse : le vendredi 14 septembre à 17h, en présence des artistes et des commissaires Les 14, 15, 16 septembre, le Centre national des arts scène les vies possibles des œuvres d’art. L’amphithéâtre plastiques (Cnap) ouvre exceptionnellement, avant mobile imaginé par Olivier Vadrot, Cavea, accueille la parole travaux, les portes de sa « nouvelle adresse » à Pantin. d’artistes invités à partager Des images secrètes, images mentales qui viennent peupler fugacement les espaces. Le temps d’un week-end, le Cnap invite à expérimenter le Concerts, performances sonores et playlists diffusés par site : performances, musiques et paroles live, œuvres in situ, L’Écouteur (un salon d’écoute conçu par Jean-Yves Leloup et salon d’écoute et cinéma éphémères participent du bivouac. Laurent Massaloux) font résonner le bâtiment de vibrations Une nuit de fête prolonge la soirée inaugurale. électro-acoustiques, d’hymnes et de confidences. L’art s’immisce pour la première fois dans le bâtiment et La soirée du vendredi 14, élaborée avec le CND, ouvre le Cnap fait ses premiers pas dans son nouveau voisinage les festivités avec une performance inédite de Monster pantinois, en partenariat avec le Centre national de la danse Chetwynd et un concert de Shrouded & The Dinner (CND) et le Centre national édition art image (Cneai).