Crowns and Bridges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concurrent Occurrence of Bilateral Hypodontia and Microdontia in a Nonsyndromic Paediatric Patient: a Case Report

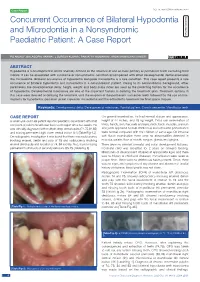

Case Report DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2020/43540.14083 Concurrent Occurrence of Bilateral Hypodontia Dentistry Section and Microdontia in a Nonsyndromic Paediatric Patient: A Case Report PG ANJALI1, BALAGOpaL VARMA2, J SURESH KUMAR3, paRVATHY KUMARAN4, ARUN MAMACHAN XAVIER5 ABSTRACT Hypodontia is a developmental dental anomaly defined as the absence of one or more primary or permanent teeth excluding third molars. It can be associated with syndrome or nonsyndromic condition accompanied with other developmental dental anomalies like microdontia. Bilateral occurrence of hypodontia alongside microdontia is a rare condition. This case report presents a rare occurrence of bilateral hypodontia and microdontia in a nonsyndromic patient. Owing to its nonsyndromic background, other parameters like developmental delay, height, weight and body mass index are used as the predicting factors for the occurrence of hypodontia. Developmental milestones are one of the important factors in deriving the treatment plan. Treatment options in this case were directed at delaying the treatment until the eruption of the permanent successor teeth followed by the use of mini- implants for hypodontia, porcelain jacket crown for microdontia and the orthodontic treatment for final space closure. Keywords: Developmental delay, Developmental milestones, Familial pattern, Growth percentile, Mandibular teeth CASE REPORT On general examination, he had normal stature and appearance, A seven-year-old male patient reported paediatric department with chief height of 44 inches, and 18 kg weight. Extra oral examination of complaint of pain in the left lower back tooth region since two weeks. He limbs, hands, skin, hair, nails and eyes, neck, back, muscles, cranium was clinically diagnosed with multiple deep dental caries (74,75,84,85) and joints appeared normal. -

Resin-Bonded Bridges − the Problem Or the Solution?: Part 1 Assessment and Design

RestorativeDentistry Jasneet Singh Gulati Sara Tabiat-Pour, Sophie Watkins and Avijit Banerjee Resin-Bonded Bridges − the Problem or the Solution?: Part 1 Assessment and Design Abstract: Resin-bonded bridges (RBBs) have an important role to play in the minimally invasive prosthodontic replacement of missing teeth. This treatment modality is perceived to have a high clinical failure rate by some practitioners, which may be associated with poorly planned and executed designs and adhesive techniques. This paper, the first part of a two-part series, discusses the important planning stages in the successful provision of RBBs, including assessment, appropriate abutment selection and design considerations. The second part of this series will focus on the clinical stages of RBB provision. CPD/Clinical Relevance: This paper aims to provide the general dental practitioner with a guide to appropriate case selection and an overview of the planning stages involved for the provision of RBBs. Dent Update 2016; 43: 506–521 How long can RBBs last? of 87.7% at 5 years,2 deeming them an When can RBBs be used? Resin-bonded bridges (RBBs) acceptable and minimally invasive (MI) RBBs have an important role have been used to replace teeth in short method of restoring modest-sized spaces to play in restorative dentistry, with edentulous spans with increasing success in the dental arch. It has often been their indications extending beyond the since the 1970s.1 A systematic review by considered that they are an under-utilized replacement of lateral incisors. They -

Section I the Patient BLUK133-Jacobsen December 7, 2007 16:38

BLUK133-Jacobsen December 7, 2007 16:38 Section I The Patient BLUK133-Jacobsen December 7, 2007 16:38 “I’m ready when you are.” 2 BLUK133-Jacobsen December 7, 2007 16:38 Chapter 1 The Patient – His Limitations and Expectations Section I The provision of high-quality restorative dentistry depends upon the dentist: Making an accurate diagnosis Devising a comprehensive and realistic treatment plan Executing the treatment plan to a high technical standard Providing subsequent continuing care There is a very strong tendency, particularly in the and here re-education is often necessary to bring him field of fixed prosthodontics, for the dentist to become down to the practical and feasible. over-interested in the technical execution of treat- It might be that the dentist has the skills and tech- ment. There is a vast range of materials and equip- nical facilities to perform advanced procedures, but ment to stimulate this interest and compete for his before he puts bur to tooth, he must stop and ask attention. It is perhaps inevitable that dentists can be- whether this is really what this patient needs and come obsessive about types of bur or root canal file, wants. If the answer is no, then to proceed is an act the pros and cons of various materials and the precise of pure selfishness that might also be regarded as techniques of restoration. negligent! This is not to decry such interest because a high Certainly the dentist may have certain treatment standard of technical execution is essential for the goals for all his patients – no pain or caries, healthy longevity of restorations. -

February 2018 (PDF File)

Member Newsletter BSSPD Annual Conference 15th/16th March 2018 Photograph: Dr. Alejandro Umanzor at Unidad de Prostodoncia Dental Pensando a future. The British Society of Prosthodontics Newsletter, Volume 24, February 2018 President’s Editorial Phil Smith I’m delighted to welcome you to the latest edition of the newsletter of the British Society of Prosthodontics. I am pleased to report that the Society has been active on several fronts over the past year. One of our functions is the delivery of suitable platform to allow Council education and CPD opportunities in Discussions to take place online without Prosthodontics and related disciplines. the need for face to face meetings. This is One way we fulfil this important gaining more importance as in recent commitment is through our annual series times it has become difficult and of Webinars. We are fortunate to have increasingly expensive for Council to take been able to assemble an impressive line- time away from clinics. We have had a up of presenters who provided our series of ‘screen tests’ and have found a members with invaluable learning updates platform that suits our needs and hopefully in a wide range of contemporary this will allow Council to become better Prosthodontic and related topics. The connected when we need to work on your Webinars attract many participants but behalf. there are some members who have yet to experience them and I would encourage BSSPD current and future Presidents have you all to sample some of them. You will also been involved in initial discussions to need to sign up to join our live Webinars, explore how we can work closer with RD- but all members are able to access our UK and BSRD on areas of mutual benefit. -

Dentistry: Advanced Research Kalghoum I, Et Al

Dentistry: Advanced Research Kalghoum I, et al. Dentistry Adv Res: DTAR-133. Case Report DOI: 10.29011/2574-7347. 100033 All Ceramic Bonded Bridge: Clinical Procedure and Requirements Imen Kalghoum1, Ines Azzouzi1, Amina Khiari1, Dalenda Hadyaoui2*, Belhssan Harzallah2, Mounir Cherif2 1DDM, Department of Fixed Prosthodontics, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Monastir, Tunisia 2Professor, Department of Fixed Prosthodontics, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Monastir, Tunisia *Corresponding author: Dalenda Hadyaoui, Professor, Department of Fixed Prosthodontics, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Mona- stir, Tunisia. Tel: +21655967860; Email: [email protected] Citation: Kalghoum I, Azzouzi I, Khiari A, Hadyaoui D, Harzallah B, et al. (2017) All Ceramic Bonded Bridge: Clinical Procedure and Requirements. Dentistry Adv Res: DTAR-133. DOI: 10.29011/2574-7347. 100033 Received Date: 05 September, 2017; Accepted Date: 18 September, 2017; Published Date: 25 September, 2017 Abstract One of the basic principles of tooth preparation for fixed prosthodontics is conservation of tooth structure. This is the ma- jor advantage of bonded bridge as an alternative to implant retained restorations in the esthetic zone. Especially used for juvenile patient who do not come into consideration for implant therapy?. This article describes the use of an all ceramic resin-bonded bridge as a conservative and esthetic solution for the replacement of 2 mandibular incisors for a 17 -year female patient. Keywords: All Ceramic Resin Bonded Bridge; Esthetic Pros- alumina ceramic, -

Gracis S. a Simplified Method to Develop An

CLINICAL RESEARCH A simplified method to develop an interdisciplinary treatment plan: an esthetically and functionally driven approach in three steps Stefano Gracis, DMD, MSD Private Practice, Milan, Italy Correspondence to: Dr Stefano Gracis Via Brera 28/a, 20121 Milan, Italy; Tel: +39 02 72094471; Email: [email protected] 76 | The International Journal of Esthetic Dentistry | Volume 16 | Number 1 | Spring 2021 GRACIS Abstract typically required. This article provides a practical step- by-step approach to planning comprehensive interdis- Many clinicians are unsure of how to develop a com- ciplinary treatment focused primarily on the teeth as prehensive plan of treatment for patients who present they relate to each other and to the structures that with multiple problems and pathologies. In order to surround them. The approach is based on the answers efficiently plan appropriate treatment for such com- to six questions that are grouped into three steps: 1) plex patient cases, the clinician needs to either have or evaluation of the teeth relative to the face and lips; develop the necessary knowledge of evidence-based 2) assessment of anterior tooth dimensions; and 3) information on the predictability of available clinical analysis of the anteroposterior and maxillomandibular procedures. The clinician also needs to understand relationships. The information obtained must then be the correct sequence in which such treatment is ap- related to the patient’s skeletal framework, periodontal plied, and perfect the skills required for carrying out status, caries susceptibility, and biomechanical risk as- that treatment. Since most clinicians have not ac- sessment in order to formulate a clear and complete quired all the knowledge and skills necessary for this plan of treatment. -

Biodental Engineering V

BIODENTAL ENGINEERING V PROCEEDINGS OF THE 5TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON BIODENTAL ENGINEERING, PORTO, PORTUGAL, 22–23 JUNE 2018 Biodental Engineering V Editors J. Belinha Instituto Politécnico do Porto, Porto, Portugal R.M. Natal Jorge, J.C. Reis Campos, Mário A.P. Vaz & João Manuel R.S. Tavares Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal CRC Press/Balkema is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2019 Taylor & Francis Group, London, UK Typeset by V Publishing Solutions Pvt Ltd., Chennai, India All rights reserved. No part of this publication or the information contained herein may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written prior permission from the publisher. Although all care is taken to ensure integrity and the quality of this publication and the information herein, no responsibility is assumed by the publishers nor the author for any damage to the property or persons as a result of operation or use of this publication and/or the information contained herein. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: International Conference on Biodental Engineering (5th: 2018: Porto, Portugal), author. | Belinha, Jorge, editor. | Jorge, Renato M. Natal editor. | Campos, J.C. Reis, editor. | Vaz, Mario A.P., editor. | Tavares, Joao Manuel R.S., editor. Title: Biodental engineering V: proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Biodental Engineering, Porto, Portugal, 22–23 June 2018 / editors, J. Belinha, R.M. Natal Jorge, J.C. Reis Campos, Mario A.P. Vaz & Joao Manuel R.S. Tavares. Description: London, UK; Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index. -

HIV/ I S and Its Significance for the Ental Profession Remember To

JOURNAL OF THE CANADIAN DENTAL ASSOCIATION December 2007/JanuaryJC 2008, Vol. 73, No. 10 DAwww.cda-adc.ca/jcda Remember to Register for the ODA Annual Spring Meeting in Conjunction with CDA in Toronto pril 10-12, 2008 HIV/I�S and its Significance for the Dental Profession PM40064661 R09961 ���JCDA • www.cda-adc.ca/jcda • December 2007/January 2008, Vol. 73, No. 10 • 861 Essential reading for Canadian dentists Straumann p/u Nov 07, p. 750 E/F 4/C December 2007/January 2008, Vol. 73, No. 10 Publisher Canadian Dental Association Mission Statement Editor-In-Chief The Canadian Dental Association is the national voice for dentistry, dedicated to Dr. John P. O’Keefe the advancement and leadership of a unified profession and to the promotion of Writer/Editor optimal oral health, an essential component of general health. Emilie Adams Assistant Editor Natalie Blais A S S O C I AT E E DITORS Coordinator, French Dr. Michael J. Casas Translation Dr. Anne Charbonneau Nathalie Upton Dr. Mary E. McNally Coordinator, Publications Rachel Galipeau Writer, Electronic Media EDITORIAL CONSULTANTS David Shaw Dr. James L. Armstrong Dr. Robert J. Hawkins Dr. Richard B. Price Manager, Design & Production Dr. Catalena Birek Dr. Asbjørn Jokstad Dr. N. Dorin Ruse Barry Sabourin Dr. Gary A. Clark Dr. Richard Komorowski Dr. Kathy Russell Dr. Jeff Coil Dr. Ernest W. Lam Dr. George K.B. Sándor Graphic Designer Dr. Pierre C. Desautels Dr. Gilles Lavigne Dr. Benoit Soucy Janet Cadeau-Simpson Dr. Terry Donovan Dr. James L. Leake Dr. David J. Sweet All statements of opinion and Dr. -

Discuss Before Fabricating: Communicating the Realities of Par Tial Den T U R E Th E R a P Y

C L I N I C A L P R A C T I C E Discuss Before Fabricating: Communicating the Realities of Par tial Den t u r e Th e r a p y . Par t II: Clinical Out c o m e s • Nita M. Mazurat, DDS • • Randall D. Mazurat, BSc, DDS, MDEd • A b s t r a c t The premise of this review is that patients’ satisfaction (and hence compliance) with partial denture therapy may be better if they are more fully informed about the limitations of the prosthesis they are to receive. Neither the dentist nor the patient should assume that all of their respective expectations will be mutually understood and inherently met. By discussing patient-centred issues and predictable clinical outcomes, both dentist and patient will be better prepared to determine whether a removable prosthesis is appropriate. Searches of the Cochrane Collaboration and MEDLINE databases were conducted to identify issues pertaining to patient compliance in wearing cast removable partial dentures. In addition to the 2 most frequent patient concerns, esthetics and mastication, discussed in the first article of this series, additional aspects of concern to the dentist and the patient when considering a removable partial denture include overeruption, post-insertion care, comfort, longevity of the prosthesis, effect on speech and biologic consequences are discussed here. MeSH Key Words: denture, partial, removable; prosthodontics; treatment outcomes © J Can Dent Assoc 2003; 69(2):96–100 This article has been peer reviewed. o re than a quarter of all re m ovable part i a l Materials and Methods dentures (RPDs) fabricated are deemed unsuc- Searches of the Cochrane Collaboration and MEDLINE M cessful,1 where failure is defined as refusal or databases were conducted between January and April 2002 inability to wear the denture. -

Herbert T. Shillingburg, Jr

Herbert T. Shillingburg, Jr, DDS David Ross Boyd Professor Emeritus Department of Fixed Prosthodontics University of Oklahoma College of Dentistry Oklahoma City, Oklahoma with David A. Sather, DDS Edwin L. Wilson, Jr, DDS, MEd Joseph R. Cain, DDS, MS Donald L. Mitchell, DDS, MS Luis J. Blanco, DMD, MS James C. Kessler, DDS Illustrations by Suzan E. Stone Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc Chicago, Berlin, Tokyo, London, Paris, Milan, Barcelona, Istanbul, Moscow, New Delhi, Prague, São Paulo, and Warsaw Cover design based on a photograph of Monument Valley on the Navajo Reservation in northern Arizona taken at sunrise by Dr Herbert T. Shillingburg, Jr. Contents Dedication vii Authors viii Preface ix Acknowledgments x 1 An Introduction to Fixed Prosthodontics 1 2 Fundamentals of Occlusion 13 3 Articulators 27 4 Interocclusal Records 35 5 Articulation of Casts 45 6 Treatment Planning for Single-Tooth Restorations 71 7 Treatment Planning for the Replacement of Missing Teeth 81 8 Fixed Partial Denture and Implant Con!gurations 99 9 Principles of Tooth Preparations 131 10 Preparations for Full Coverage Crowns 149 11 Preparations for Partial Coverage Crowns 165 12 Preparations for Intracoronal Restorations 193 13 Preparations for Severely Debilitated Teeth 203 14 Preparations for Periodontally Weakened Teeth 229 15 Provisional Restorations 241 16 Fluid Control and Soft Tissue Management 269 291 17 Impressions 325 18 Working Casts and Dies 343 19 Wax Patterns 363 20 Investing and Casting 383 21 Cementation and Bonding 413 22 Esthetic Considerations 425 23 All-Ceramic Restorations 447 24 Metal-Ceramic Restorations 471 25 Pontics and Edentulous Ridges 493 26 Solder Joints and Other Connectors 517 27 Restoration of Osseointegrated Dental Implants 531 28 Single-Tooth Implant Restoration 543 29 Multiple-Tooth Implant Restoration Index 555 Dedication In Memoriam Constance Murphy Shillingburg 1938–2008 This book is dedicated to the loving memory of Constance surgeries later in life, she was the most optimistic person I Murphy Shillingburg. -

Resin-Bonded Bridges − the Problem Or the Solution? Part 1: Assessment and Design

RestorativeDentistry Jasneet Singh Gulati Sara Tabiat-Pour, Sophie Watkins and Avijit Banerjee Resin-Bonded Bridges − the Problem or the Solution? Part 1: Assessment and Design Abstract: Resin-bonded bridges (RBBs) have an important role to play in the minimally invasive prosthodontic replacement of missing teeth. This treatment modality is perceived to have a high clinical failure rate by some practitioners, which may be associated with poorly planned and executed designs and adhesive techniques. This paper, the first part of a two-part series, discusses the important planning stages in the successful provision of RBBs, including assessment, appropriate abutment selection and design considerations. The second part of this series will focus on the clinical stages of RBB provision. CPD/Clinical Relevance: This paper aims to provide the general dental practitioner with a guide to appropriate case selection and an overview of the planning stages involved for the provision of RBBs. Dent Update 2016; 43: 506–521 How long can RBBs last? of 87.7% at 5 years,2 deeming them an When can RBBs be used? Resin-bonded bridges (RBBs) acceptable and minimally invasive (MI) RBBs have an important role have been used to replace teeth in short method of restoring modest-sized spaces to play in restorative dentistry, with edentulous spans with increasing success in the dental arch. It has often been their indications extending beyond the since the 1970s.1 A systematic review by considered that they are an under-utilized replacement of lateral incisors. They -

Creating Brighter Futures Aesthetics & Teamwork

University of Sydney Aesthetics & Teamwork Creating Brighter Futures Aesthetics & Teamwork Utilizing an Interdisciplinary Approach to Enhance Anterior • The gingival margins of the central incisors should be Dental Aesthetics positioned 0.5-1mm apical to the lateral incisors and should be at the same level as the canines. The general goals of orthodontic treatment are to establish • The contour of the labial gingival margins should follow a good occlusion, enhance periodontal health, and improve the CEJ of the teeth. dental and facial aesthetics. In the past, greater emphasis has been placed on achieving ideal alignment and a good • There should be a papilla between each tooth, which occlusal result, with less emphasis being placed on occupies the apical half of the interproximal contact. periodontal health and the aesthetic appearance of individual teeth. In some patients, well-aligned teeth may still The following situations can detract from an aesthetically look unaesthetic. A “gummy smile”, uneven gingival margins pleasing smile. and crown heights, worn teeth, missing papillae and abnormal tooth morphology can jeopardize the aesthetic 1. The “Gummy Smile” appearance of teeth. In many cases, these unaesthetic situations can be improved through a coordinated The “gummy smile” has three potential causes. It may be teamwork approach of orthodontics, periodontics and the result of excessive vertical maxillary growth, which is restorative dentistry. most often managed with a combined orthodontic and orthognathic surgery treatment approach. Secondly, a “gummy smile” may be caused by delayed apical migration What Contributes to an of the gingival margin, or thirdly, overeruption of the Aesthetically Pleasing Smile? maxillary anterior teeth.The management of the latter two causes is determined by probing the sulcular depth of the Having well-aligned teeth is not the only factor that maxillary anterior teeth.