Potential and Capactiors.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

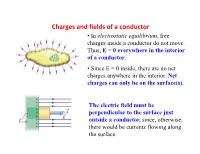

Charges and Fields of a Conductor • in Electrostatic Equilibrium, Free Charges Inside a Conductor Do Not Move

Charges and fields of a conductor • In electrostatic equilibrium, free charges inside a conductor do not move. Thus, E = 0 everywhere in the interior of a conductor. • Since E = 0 inside, there are no net charges anywhere in the interior. Net charges can only be on the surface(s). The electric field must be perpendicular to the surface just outside a conductor, since, otherwise, there would be currents flowing along the surface. Gauss’s Law: Qualitative Statement . Form any closed surface around charges . Count the number of electric field lines coming through the surface, those outward as positive and inward as negative. Then the net number of lines is proportional to the net charges enclosed in the surface. Uniformly charged conductor shell: Inside E = 0 inside • By symmetry, the electric field must only depend on r and is along a radial line everywhere. • Apply Gauss’s law to the blue surface , we get E = 0. •The charge on the inner surface of the conductor must also be zero since E = 0 inside a conductor. Discontinuity in E 5A-12 Gauss' Law: Charge Within a Conductor 5A-12 Gauss' Law: Charge Within a Conductor Electric Potential Energy and Electric Potential • The electrostatic force is a conservative force, which means we can define an electrostatic potential energy. – We can therefore define electric potential or voltage. .Two parallel metal plates containing equal but opposite charges produce a uniform electric field between the plates. .This arrangement is an example of a capacitor, a device to store charge. • A positive test charge placed in the uniform electric field will experience an electrostatic force in the direction of the electric field. -

Energetics of a Turbulent Ocean

Energetics of a Turbulent Ocean Raffaele Ferrari January 12, 2009 1 Energetics of a Turbulent Ocean One of the earliest theoretical investigations of ocean circulation was by Count Rumford. He proposed that the meridional overturning circulation was driven by temperature gradients. The ocean cools at the poles and is heated in the tropics, so Rumford speculated that large scale convection was responsible for the ocean currents. This idea was the precursor of the thermohaline circulation, which postulates that the evaporation of water and the subsequent increase in salinity also helps drive the circulation. These theories compare the oceans to a heat engine whose energy is derived from solar radiation through some convective process. In the 1800s James Croll noted that the currents in the Atlantic ocean had a tendency to be in the same direction as the prevailing winds. For example the trade winds blow westward across the mid-Atlantic and drive the Gulf Stream. Croll believed that the surface winds were responsible for mechanically driving the ocean currents, in contrast to convection. Although both Croll and Rumford used simple theories of fluid dynamics to develop their ideas, important qualitative features of their work are present in modern theories of ocean circulation. Modern physical oceanography has developed a far more sophisticated picture of the physics of ocean circulation, and modern theories include the effects of phenomena on a wide range of length scales. Scientists are interested in understanding the forces governing the ocean circulation, and one way to do this is to derive energy constraints on the differ- ent processes in the ocean. -

Maxwell's Equations

Maxwell’s Equations Matt Hansen May 20, 2004 1 Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 The basics 3 2.1 Static charges . 3 2.2 Moving charges . 4 2.3 Magnetism . 4 2.4 Vector operations . 5 2.5 Calculus . 6 2.6 Flux . 6 3 History 7 4 Maxwell’s Equations 8 4.1 Maxwell’s Equations . 8 4.2 Gauss’ law for electricity . 8 4.3 Gauss’ law for magnetism . 10 4.4 Faraday’s law . 11 4.5 Ampere-Maxwell law . 13 5 Conclusion 14 2 1 Introduction If asked, most people outside a physics department would not be able to identify Maxwell’s equations, nor would they be able to state that they dealt with electricity and magnetism. However, Maxwell’s equations have many very important implications in the life of a modern person, so much so that people use devices that function off the principles in Maxwell’s equations every day without even knowing it. 2 The basics 2.1 Static charges In order to understand Maxwell’s equations, it is necessary to understand some basic things about electricity and magnetism first. Static electricity is easy to understand, in that it is just a charge which, as its name implies, does not move until it is given the chance to “escape” to the ground. Amounts of charge are measured in coulombs, abbreviated C. 1C is an extraordi- nary amount of charge, chosen rather arbitrarily to be the charge carried by 6.41418 · 1018 electrons. The symbol for charge in equations is q, sometimes with a subscript like q1 or qenc. -

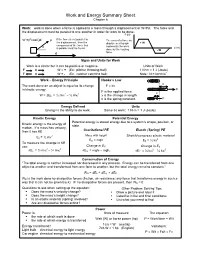

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6 Work: work is done when a force is applied to a mass through a displacement or W=Fd. The force and the displacement must be parallel to one another in order for work to be done. F (N) W =(Fcosθ)d F If the force is not parallel to The area of a force vs. the displacement, then the displacement graph + W component of the force that represents the work θ d (m) is parallel must be found. done by the varying - W d force. Signs and Units for Work Work is a scalar but it can be positive or negative. Units of Work F d W = + (Ex: pitcher throwing ball) 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) F d W = - (Ex. catcher catching ball) Note: N = kg m/s2 • Work – Energy Principle Hooke’s Law x The work done on an object is equal to its change F = kx in kinetic energy. F F is the applied force. 2 2 x W = ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi x is the change in length. k is the spring constant. F Energy Defined Units Energy is the ability to do work. Same as work: 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) Kinetic Energy Potential Energy Potential energy is stored energy due to a system’s shape, position, or Kinetic energy is the energy of state. motion. If a mass has velocity, Gravitational PE Elastic (Spring) PE then it has KE 2 Mass with height Stretch/compress elastic material Ek = ½ mv 2 EG = mgh EE = ½ kx To measure the change in KE Change in E use: G Change in ES 2 2 2 2 ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi ΔEG = mghf – mghi ΔEE = ½ kxf – ½ kxi Conservation of Energy “The total energy is neither increased nor decreased in any process. -

Electro Magnetic Fields Lecture Notes B.Tech

ELECTRO MAGNETIC FIELDS LECTURE NOTES B.TECH (II YEAR – I SEM) (2019-20) Prepared by: M.KUMARA SWAMY., Asst.Prof Department of Electrical & Electronics Engineering MALLA REDDY COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY (Autonomous Institution – UGC, Govt. of India) Recognized under 2(f) and 12 (B) of UGC ACT 1956 (Affiliated to JNTUH, Hyderabad, Approved by AICTE - Accredited by NBA & NAAC – ‘A’ Grade - ISO 9001:2015 Certified) Maisammaguda, Dhulapally (Post Via. Kompally), Secunderabad – 500100, Telangana State, India ELECTRO MAGNETIC FIELDS Objectives: • To introduce the concepts of electric field, magnetic field. • Applications of electric and magnetic fields in the development of the theory for power transmission lines and electrical machines. UNIT – I Electrostatics: Electrostatic Fields – Coulomb’s Law – Electric Field Intensity (EFI) – EFI due to a line and a surface charge – Work done in moving a point charge in an electrostatic field – Electric Potential – Properties of potential function – Potential gradient – Gauss’s law – Application of Gauss’s Law – Maxwell’s first law, div ( D )=ρv – Laplace’s and Poison’s equations . Electric dipole – Dipole moment – potential and EFI due to an electric dipole. UNIT – II Dielectrics & Capacitance: Behavior of conductors in an electric field – Conductors and Insulators – Electric field inside a dielectric material – polarization – Dielectric – Conductor and Dielectric – Dielectric boundary conditions – Capacitance – Capacitance of parallel plates – spherical co‐axial capacitors. Current density – conduction and Convection current densities – Ohm’s law in point form – Equation of continuity UNIT – III Magneto Statics: Static magnetic fields – Biot‐Savart’s law – Magnetic field intensity (MFI) – MFI due to a straight current carrying filament – MFI due to circular, square and solenoid current Carrying wire – Relation between magnetic flux and magnetic flux density – Maxwell’s second Equation, div(B)=0, Ampere’s Law & Applications: Ampere’s circuital law and its applications viz. -

Innovation Insights Brief | 2020

FIVE STEPS TO ENERGY STORAGE Innovation Insights Brief | 2020 In collaboration with the California Independent System Operator (CAISO) ABOUT THE WORLD ENERGY COUNCIL ABOUT THIS INSIGHTS BRIEF The World Energy Council is the principal impartial This Innovation Insights brief on energy storage is part network of energy leaders and practitioners promoting of a series of publications by the World Energy Council an affordable, stable and environmentally sensitive focused on Innovation. In a fast-paced era of disruptive energy system for the greatest benefit of all. changes, this brief aims at facilitating strategic sharing of knowledge between the Council’s members and the Formed in 1923, the Council is the premiere global other energy stakeholders and policy shapers. energy body, representing the entire energy spectrum, with over 3,000 member organisations in over 90 countries, drawn from governments, private and state corporations, academia, NGOs and energy stakeholders. We inform global, regional and national energy strategies by hosting high-level events including the World Energy Congress and publishing authoritative studies, and work through our extensive member network to facilitate the world’s energy policy dialogue. Further details at www.worldenergy.org and @WECouncil Published by the World Energy Council 2020 Copyright © 2020 World Energy Council. All rights reserved. All or part of this publication may be used or reproduced as long as the following citation is included on each copy or transmission: ‘Used by permission of the World -

Hydroelectric Power -- What Is It? It=S a Form of Energy … a Renewable Resource

INTRODUCTION Hydroelectric Power -- what is it? It=s a form of energy … a renewable resource. Hydropower provides about 96 percent of the renewable energy in the United States. Other renewable resources include geothermal, wave power, tidal power, wind power, and solar power. Hydroelectric powerplants do not use up resources to create electricity nor do they pollute the air, land, or water, as other powerplants may. Hydroelectric power has played an important part in the development of this Nation's electric power industry. Both small and large hydroelectric power developments were instrumental in the early expansion of the electric power industry. Hydroelectric power comes from flowing water … winter and spring runoff from mountain streams and clear lakes. Water, when it is falling by the force of gravity, can be used to turn turbines and generators that produce electricity. Hydroelectric power is important to our Nation. Growing populations and modern technologies require vast amounts of electricity for creating, building, and expanding. In the 1920's, hydroelectric plants supplied as much as 40 percent of the electric energy produced. Although the amount of energy produced by this means has steadily increased, the amount produced by other types of powerplants has increased at a faster rate and hydroelectric power presently supplies about 10 percent of the electrical generating capacity of the United States. Hydropower is an essential contributor in the national power grid because of its ability to respond quickly to rapidly varying loads or system disturbances, which base load plants with steam systems powered by combustion or nuclear processes cannot accommodate. Reclamation=s 58 powerplants throughout the Western United States produce an average of 42 billion kWh (kilowatt-hours) per year, enough to meet the residential needs of more than 14 million people. -

The Mechanical Equivalent of Heat

THE MECHANICAL EQUIVALENT OF HEAT INTRODUCTION This is the classic experiment, first performed in 1847 by James Joule, which led to our modern view that mechanical work and heat are but different aspects of the same quantity: energy. The classic experiment related the two concepts and provided a connection between the Joule, defined in terms of mechanical variables (work, kinetic energy, potential energy. etc.) and the calorie, defined as the amount of heat that raises the temperature of 1 gram of water by 1 degree Celsius. Contemporary SI units do not distinguish between heat energy and mechanical energy, so that heat is also measured in Joules. In this experiment, work is done by rubbing two metal cones, which raises the temperature of a known amount of water (along with the cones, stirrer, thermometer, etc,). The ratio of the mechanical work done (W) to the heat which has passed to the water plus parts (Q), determines the constant J (J = W/Q). THE EXPERIMENT CAUTION: The apparatus must not be operated without oil between the cones. The cones have to be cleaned and a tiny drop of oil put between the rubbing surfaces (caution! too much oil will reduce the friction excessively and make the experiment impossible). The apparatus is shown in Figure 1. The heat generated in the system is absorbed by different parts: the water, the inner and outer cones, the stirrer and the immersed part of the temperature probe. The total increase in heat, including all these contributions, is therefore: Q = (MCw + M′Cbr + v Cth) ∆T = constant1 × ∆T (1) -1 -1 Cw = specific heat of water = 1.00 cal g C (by definition of the calorie) -1 ° -1 Cbr = specific heat of brass (cones and stirrer) = 0.089 cal g C -3 ° -1 Cth = heat capacity per unit volume of temperature probe = 0.013 cal cm C M = mass of water (in g) M′ = mass of cones and stirrer (in g) v = volume of the immersed part of the temperature probe (in cm3). -

Hydropower Technologies Program — Harnessing America’S Abundant Natural Resources for Clean Power Generation

U.S. Department of Energy — Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Wind & Hydropower Technologies Program — Harnessing America’s abundant natural resources for clean power generation. Contents Hydropower Today ......................................... 1 Enhancing Generation and Environmental Performance ......... 6 Large Turbine Field-Testing ............................... 9 Providing Safe Passage for Fish ........................... 9 Improving Mitigation Practices .......................... 11 From the Laboratories to the Hydropower Communities ..... 12 Hydropower Tomorrow .................................... 14 Developing the Next Generation of Hydropower ............ 15 Integrating Wind and Hydropower Technologies ............ 16 Optimizing Project Operations ........................... 17 The Federal Wind and Hydropower Technologies Program ..... 19 Mission and Goals ...................................... 20 2003 Hydropower Research Highlights Alden Research Center completes prototype turbine tests at their facility in Holden, MA . 9 Laboratories form partnerships to develop and test new sensor arrays and computer models . 10 DOE hosts Workshop on Turbulence at Hydroelectric Power Plants in Atlanta . 11 New retrofit aeration system designed to increase the dissolved oxygen content of water discharged from the turbines of the Osage Project in Missouri . 11 Low head/low power resource assessments completed for conventional turbines, unconventional systems, and micro hydropower . 15 Wind and hydropower integration activities in 2003 aim to identify potential sites and partners . 17 Cover photo: To harness undeveloped hydropower resources without using a dam as part of the system that produces electricity, researchers are developing technologies that extract energy from free flowing water sources like this stream in West Virginia. ii HYDROPOWER TODAY Water power — it can cut deep canyons, chisel majestic mountains, quench parched lands, and transport tons — and it can generate enough electricity to light up millions of homes and businesses around the world. -

Fuel Wise Or Fuelish? Grades 9 to 12

LESSON PLAN Fuel Wise or Fuelish? Grades 9 to 12 SUMMARY LESSON OBJECTIVES In this lesson, the students will explore the different impacts Upon completing this lesson the students will: using alternative fuels has on the economy. • Learn how world events affect supply and demand for The students will research and compare different cars. petroleum; They will determine the cost of operation for one year to • Explore why it is important for South Carolinians to use include price, fuel, insurance, property taxes, title, tag, and alternative fuels; and maintenance, as well as determine the most cost-effective choice of vehicle, based on their research. • Make decisions pertinent to choosing a fuel-efficient car. ESSENTIAL QUESTION How have alternative fuels impacted the economy? DURATION The activity requires about one to two weeks to complete. 2014 S.C. SCIENCE STANDARDS CORRELATIONS Standard H.P.3: The student will demonstrate an understanding of how the interactions among objects can be explained and predicted using the concept of the conservation of energy. CONCEPTUAL UNDERSTANDING H.P.3A.: Work and energy are equivalent to each other. Work is defined as the product of displacement and the force causing that displacement; this results in the transfer of mechanical energy. Therefore, in the case of mechanical energy, energy is seen as the ability to do work. This is called the work-energy principle. The rate at which work is done (or energy is transformed) is called power. For machines that do useful work for humans, the ratio of useful power output is the efficiency of the machine. -

Electromagnetic Fields and Energy

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu Haus, Hermann A., and James R. Melcher. Electromagnetic Fields and Energy. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1989. ISBN: 9780132490207. Please use the following citation format: Haus, Hermann A., and James R. Melcher, Electromagnetic Fields and Energy. (Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT OpenCourseWare). http://ocw.mit.edu (accessed [Date]). License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike. Also available from Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1989. ISBN: 9780132490207. Note: Please use the actual date you accessed this material in your citation. For more information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms 8 MAGNETOQUASISTATIC FIELDS: SUPERPOSITION INTEGRAL AND BOUNDARY VALUE POINTS OF VIEW 8.0 INTRODUCTION MQS Fields: Superposition Integral and Boundary Value Views We now follow the study of electroquasistatics with that of magnetoquasistat ics. In terms of the flow of ideas summarized in Fig. 1.0.1, we have completed the EQS column to the left. Starting from the top of the MQS column on the right, recall from Chap. 3 that the laws of primary interest are Amp`ere’s law (with the displacement current density neglected) and the magnetic flux continuity law (Table 3.6.1). � × H = J (1) � · µoH = 0 (2) These laws have associated with them continuity conditions at interfaces. If the in terface carries a surface current density K, then the continuity condition associated with (1) is (1.4.16) n × (Ha − Hb) = K (3) and the continuity condition associated with (2) is (1.7.6). a b n · (µoH − µoH ) = 0 (4) In the absence of magnetizable materials, these laws determine the magnetic field intensity H given its source, the current density J. -

Mechanical Energy

Chapter 2 Mechanical Energy Mechanics is the branch of physics that deals with the motion of objects and the forces that affect that motion. Mechanical energy is similarly any form of energy that’s directly associated with motion or with a force. Kinetic energy is one form of mechanical energy. In this course we’ll also deal with two other types of mechanical energy: gravitational energy,associated with the force of gravity,and elastic energy, associated with the force exerted by a spring or some other object that is stretched or compressed. In this chapter I’ll introduce the formulas for all three types of mechanical energy,starting with gravitational energy. Gravitational Energy An object’s gravitational energy depends on how high it is,and also on its weight. Specifically,the gravitational energy is the product of weight times height: Gravitational energy = (weight) × (height). (2.1) For example,if you lift a brick two feet off the ground,you’ve given it twice as much gravitational energy as if you lift it only one foot,because of the greater height. On the other hand,a brick has more gravitational energy than a marble lifted to the same height,because of the brick’s greater weight. Weight,in the scientific sense of the word,is a measure of the force that gravity exerts on an object,pulling it downward. Equivalently,the weight of an object is the amount of force that you must exert to hold the object up,balancing the downward force of gravity. Weight is not the same thing as mass,which is a measure of the amount of “stuff” in an object.