Julie Mehretu/MATRIX 211

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Release

MEDIA RELEASE The Studio Museum in Harlem 144 West 125th Street New York, NY 10027 studiomuseum.org/press Preview: Wednesday, November 13, 2013, 6 to 7pm Contact: Liz Gwinn, Communications Manager [email protected] 646.214.2142 This Fall, the Studio Museum presents The Shadows Took Shape, an exhibition with more than 60 works by 29 artists examining Afrofuturism from a global perspective Left: Cyrus Kabiru, Nairobian Baboon (from C-Stunners series), 2012. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Amunga Eshuchi. Right: The Otolith Group, Hydra Decapita (film still), 2010. Courtesy the artists New York, NY, July 9, 2013—This fall, The Studio Museum in Harlem is thrilled to present The Shadows Took Shape, a dynamic interdisciplinary exhibition exploring contemporary art through the lens of Afrofuturist aesthetics. Coined in 1994 by writer Mark Dery in his essay “Black to the Future,” the term “Afrofuturism” refers to a creative and intellectual genre that emerged as a strategy to explore science fiction, fantasy, magical realism and pan-Africanism. With roots in the avant-garde musical stylings of sonic innovator Sun Ra (born Herman Poole Blount, 1914–1993), Afrofuturism has been used by artists, writers and theorists as a way to prophesize the future, redefine the present and reconceptualize the past. The Shadows Took Shape will be one of the few major museum exhibitions to explore the ways in which this form of creative expression has been adopted internationally and highlight the range of work made over the past twenty-five years. On view at The Studio Museum in Harlem from November 14, 2013 to March 9, 2014, the exhibition draws its title from an obscure Sun Ra poem and a posthumously released series of recordings. -

Direct Democracy, 2013, Curated By

DIRECT DEMOCRACY 1 2 DIRECT DEMOCRACY DIRECT DEMOCRACY Laylah Ali Hany Armanious Natalie Bookchin A Centre for Everything DAMP Destiny Deacon Alicia Frankovich Will French Gail Hastings Alex Martinis Roe Andrew McQualter John Miller Alex Monteith Raquel Ormella Mike Parr Simon Perry Carl Scrase Milica Tomić Kostis Velonis Jemima Wyman Curator: Geraldine Barlow Monash University Museum of Art | MUMA 26 April – 6 July 2013 7 Milica Tomic cover, back cover and pages 2-9 ‘One Day, Instead of One Night, a Burst of Machine-Gun Fire Will Flash, if Light Cannot Come Otherwise’ (Oskar Davico – fragment from a poem). Dedicated to the members of the Anarcho-Syndicalist Initiative – Belgrade, 3 September 2009 2009 8 9 10 11 12 13 John Miller pages 10-15 Tour scrums: Protesting black and blue 2007 14 15 16 17 18 19 Jemima Wyman page 16 Combat 02 2008 page 19 Combat 06 2008 page 20 Combat 08 2008 page 21 Combat drag 2008 20 21 22 23 24 25 Alicia Frankovich page 22 Slow dance 2011 page 23 Girl with a pomegranate 2012 pages 24-27 Bisons 2010 26 27 28 29 30 Kostis Velonis page 28 detail of hammers collected for Who might rebuild 2013 page 30 A sea of troubles (sail the red ship to the south) 2012 page 31 Untitled (life without tragedy) 2009 31 32 33 34 35 Hany Armanious pages 33, 35, 37 Mystery of the plinth 2010 36 37 38 39 40 A Centre for Everything (Will Foster & Gabrielle de Vietri) page 38 event documentation: Neighbourhood mapping, pesto and La révolution surréaliste 2013, top Show & tell, Ethiopian cuisine and verbal geography 2013, middle Bat talk, -

Julie Mehretu CV 2018 V5

JULIE MEHRETU 1970 Born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Lives and works in New York Education 1997 MFA, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence 1992 BA, Kalamazoo College, Michigan 1990 University Cheikh Anta Diop, Dakar, Senegal Solo exhibitions 2018 Marian Goodman Gallery (with Tacita Dean), Paris 2017 A Universal History of Everything and Nothing , Serralves Museum, Porto, Portugal; Centro Botín, Santander, Spain HOWL, eon (I, II) , San Francisco Museum of Modern Art commission 2016 Struggling With Words That Count (with Jessica Rankin), Carlier Gebauer, Berlin Hoodnyx, Voodoo and Stelae , Marian Goodman Gallery, New York The Addis Show , Gebre Kristos Desta Center, Addis Ababa Earthfold (with Jessica Rankin), Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens, Deurle, Belgium Epigraph, Damascus , Niels Borch Jensen Gallery and Editions, Berlin 2014 Half a Shadow , Carlier Gebauer, Berlin The Mathematics of Droves , White Cube, São Paulo Myriads Only By Dark , Gemini G.E.L. at Joni Moisant Weyl, New York 2013 Liminal Squared , White Cube, London Liminal Squared , Marian Goodman Gallery, New York Mind, Breath and Beat Drawings , Marian Goodman Gallery, Paris Excavations: The Prints of Julie Mehretu , School of Art and Design, Ohio University2012 Excavations: The Prints of Julie Mehretu , The Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, New York 2010 Notations After The Ring , Arnold & Marie Schwartz Gallery, Metropolitan Opera House, New York Grey Area , Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 2009 Excavations: The Prints of Julie Mehretu , High Point Prints, Minneapolis, -

PDF Press Release

P R E S S R E L E A S E FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: July 25, 2012 The Williams College Museum of Art presents Laylah Ali: The Greenheads Series August 18–November 25, 2012 Photos available upon request. Press Contact: Kim Hugo, Public Relations Coordinator; (413) 597-3352; [email protected] Williamstown, Mass. – The Williams College Museum of Art (WCMA) is pleased to present Laylah Ali: The Greenheads Series. The exhibition will be on view from August 18 to November 25, 2012. It is the first time the Greenheads series—created between 1996 and 2005—will be shown as a comprehensive body of work. Over forty of these exquisitely rendered gouache paintings—from a total of more than eighty—have been gathered from collections here and abroad to chronicle the series’ development. 15 LAWRENCE HALL DRIVE SUITE 2 WILLIAMSTOWN MASSACHUSETTS 01267-2566 telephone 413.597.2429 facsimile 413.597.5000 web WCMA.WILLIAMS.EDU The figures inhabiting Ali’s works—the Greenheads—are enigmatic round-headed beings of indeterminate sex and race who inhabit a regimented, dystopian world where odd and menacing, though sometimes strangely humorous, encounters prevail. The WCMA exhibition will allow viewers to examine the evolution of Ali’s series. While the early paintings frequently focus on physically aggressive exchanges between groups of figures, these interactions are later replaced by individuals—alone or in small groups—who witness the prelude to, or aftermath of, a charged encounter. As the series continues, more and more of the figures’ anatomy is pruned away, as if the artist is examining how much can be taken out—such as arms, feet, skin color—while still communicating thought, emotion, and social status. -

28 New Exhibitions Feature Black Artists

Their Favorite Works at the Met Mar 31, 2015 Arts Leader Mary Schmidt Campbell Named President of Spelman College Mar 29, 2015 POPULAR NOW THIS SPRING MARKS THE OPENING of a number of notable exhibitions featuring work by African and African Spring Openings: 28 New Exhibitions American artists. In Los Angeles, William Pope.L’s largest-ever museum presentation is on view at the Museum of Feature Black Artists Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. In New York, a comprehensive overview of colorful works by Alma Thomas is at Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, and June Kelly Gallery is displaying paintings by Philemona Williamson (shown above). Four African American Artists Break Records at Swann Auction The Museum of Modern Art in New York (“Migration Series”) and the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University (new acquisitions) are showing significant exhibitions by Jacob Lawrence. Several other artists have multiple shows scheduled this season, including Glenn Ligon, Yinka Shonibare, MBE, and Trenton Doyle Hancock. And, of 2015 Venice Biennale to Include More than 35 Black Artists course, the 2015 Venice Biennale featuring more than 35 black artists opens on May 9. A selection of some of http://www.culturetype.com/2015/04/08/spring-openings-28-new-exhibitions-feature-black-artists/ spring’s most intriguing offerings follows: National Gallery of Art Acquires 190+ Works by African American Artists From Corcoran Culture Talk: Duke Professor Richard J. Powell on Archibald Motley Weekend Reading: The Intersecting Worlds of Chris Ofili and David Adjaye National Gallery Curators Explain How Corcoran Works Will Enhance Collection NATIONAL GALLERY CURATORS EXPLAIN HOW CORCORAN WORKS WILL ENHANCE COLLECTION GLENN LIGON, Installation view of “Well, it’s bye-bye/If you call that gone” at Regen Projects, Los Angeles. -

Julie Mehretu CV 2018

JULIE MEHRETU 1970 Born in Addis Ababa. Lives and works in New York Education 1997 MFA, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence 1992 BA Kalamazoo College, Michigan 1990–91 University Cheik Anta Diop, Dakar Solo exhibitions 2017 Julie Mehretu: A Universal History of Everything and Nothing , Serralves Museum, Porto and Centro Botín, Santander, Spain 2016 Struggling With Words That Count (with Jessica Rankin), Carlier Gebauer, Berlin Hoodnyx , Voodoo and Stelae , Marian Goodman Gallery, New York The Addis Show , Gebre Kristos Desta Center, Addis Ababa Earthfold (with Jessica Rankin), Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens, Deurle, Belgium 2014 Half A Shadow , Carlier Gebauer, Berlin zThe Mathematics of Drove s, White Cube, São Paulo 2013 Liminal Squared , Marian Goodman Gallery, New York Liminal Squared , White Cube, London Mind, Breath and Beat Drawings , Marian Goodman Gallery, Paris 2010 Notations After The Ring , Arnold & Marie Schwartz Gallery, Metropolitan Opera House, New York Grey Area , Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 2009 Excavations: The Prints of Julie Mehretu , High Point Prints, Minneapolis Grey Area , Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin 2008 City Sitings , North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh Eye of the Storm , Carl Scholsberg Gallery, Montserrat College, Beverley City Sitings , Williams College Art Gallery, Williamstown, Massachusetts 2007 City Sitings , The Detroit Institute of Arts Black City , Kunstverein Hanover and Louisiana Museum, Humlebaek, Denmark 2006 Black City , MUSAC – Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León, Spain Heavy -

Julie Mehretu and Jason Moran. Photo by Damien Young

Julie Mehretu and Jason Moran. Photo by Damien Young. Among the performances unfolding throughout Performa 17, few have a monumental backstory like MASS (HOWL, eon), which debuts tonight at Harlem Parish. One would expect as much from either of its creators, jazz musician Jason Moran or artist Julie Mehretu—who, as collaborators, make a formidable duo indeed: Moran, considered one of his generation’s leading jazz pianists, is also a prolific composer. He began moonlighting in the art world around 2005; he’s since worked with figures like Glenn Ligon and Lorna Simpson, and frequently performs alongside Joan Jonas. He’s now represented by Luhring Augustine, and, this spring, he will have his first solo museum show at the Walker Center. Meanwhile, following Mehretu’s groundbreaking 2010 mural, which soars across 80-feet of wall just beyond the entrance to Manhattan’s Goldman Sachs building, she has continued to take her large-scale, staggeringly intricate paintings to new heights. Her latest is HOWL, eon (I, II), a diptych unveiled by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in September. She had spent more than a year completing the two massive canvases, which, with each at 27 feet tall and 32 feet wide, she accommodated by moving her studio to the cavernous nave of a shuttered church in Harlem. A Texas native, Moran graduated from the Manhattan School of Music in 1997. Not long after, he signed with Blue Note, the iconic jazz record label that launched his idol, Thelonious Monk. Moran would soon be headlining esteemed venues across New York, and, later, around the world. -

A Museum Director's Life

Published by The Internet-First University Press A Museum Director’s Life An Intimate History of the Herbert F. Johnson Museum, 1992 – 2011 Frank Robinson This essay has three purposes. First, this is a summary of what happened at the Museum during my nineteen years as Director. Second, it is a look at the “unofficial” history of that period, different from the Annual Reports. Third, this story can hopefully serve as a kind of example, a case study, of what is involved in running a small university museum, the issues and problems confronting a small non-profit organization serving a much larger organization and, at the same time, the wider community. ©2014 Cornell University and Frank Robinson Released: October 20, 2014 This book – http://dspace.library.cornell.edu/handle/1813/63 Books and Articles Collection – http://ecommons.library.cornell.edu/handle/1813/63 The Internet-First University Press – http://ecommons.library.cornell.edu/handle/1813/62 Contents Preface .............................................i I. The Mission and Purposes of a Museum.............1 II. The Staff ........................................2 III. Art . 3 IV. Education.......................................5 V. Finances and fund raising.........................7 VI. The new wing. ...................................8 VII. Directors .......................................9 See also the CORNELLCAST at Museum Tour with Frank Robinson http://www.cornell.edu/video/museum-tour-with-frank-robinson POSTED ON JUNE 3, 2011 BY HERBERT F. JOHNSON MUSEUM OF ART Abstract This video represents a snapshot of the Johnson Museum in 2011, just before the completion of the renovation and extension project. Frank Robinson, the Richard J. Schwartz Director, highlights the many signature works from the permanent collec- tion and shares his personal journey as a university museum director for more than 34 years. -

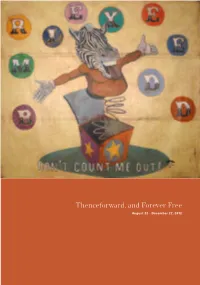

Thenceforward, and Forever Free August 22 - December 22, 2012 2

1 1 Thenceforward, and Forever Free August 22 - December 22, 2012 2 Cover image Michael Ray Charles American, b. 1967 (Forever Free) Mixed Breed, 1997 Acrylic latex, stain and copper penny on canvas tarp 99 x 111" Collection of Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York 3 Thenceforward, and Forever Free August 22 - December 22, 2012 Thenceforward, and Forever Free is presented as part of Marquette University’s Freedom Project, a yearlong commemoration of the Sesquicentennial of the Civil War. The Project explores the many histories and meanings of emancipation and freedom in the United States and beyond. The exhibition features seven contemporary artists whose work deals with issues of race, gender, privilege, and identity, and more broadly conveys interpretations of the notion of freedom. Artists in Thenceforward are: Laylah Ali, Willie Birch, Michael Ray Charles, Gary Simmons, Elisabeth Subrin, Mark Wagner, and Kara Walker. Essayists for the exhibition catalogue are Dr. A. Kristen Foster, associate professor, Department of History, Marquette University, and Ms. Kali Murray, assistant professor, Marquette University Law School. Thenceforward, and Forever Free is sponsored in part by the Friends of the Haggerty, the Joan Pick Endowment Fund, the Marquette University Andrew W. Mellon Fund, a Marquette Excellence in Diversity Grant, the Martha and Ray Smith, Jr. Endowment Fund, the Nelson Goodman Endowment Fund, and the Wisconsin Arts Board with funds from the State of Wisconsin and the National Endowment for the Arts. 4 Art and the American Paradox A. Kristen Foster, Ph.D. Associate Professor Department of History Marquette University On December 1, 1862—before signing the Emancipation Proclamation, before the end of the Civil War, and before the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment—President Abraham Lincoln sent his Annual Message to Congress. -

New Documentary Offers Touching Portrait of Collector and Philanthropist Agnes Gund

New Documentary Offers Touching Portrait of Collector and Philanthropist Agnes Gund BY MAXIMILÍANO DURÓN October 9, 2020 4:43pm A still from Aggie, showing Agnes Gund, right, doing a studio visit with artist Xaviera Simmons, left. Encapsulating the life story of Agnes Gund, one of the most beloved people in the art world, is no small task, but a new documentary called Aggie has set out to try. Long considered one of the world’s top collectors, and formerly the president of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, she more recently made headlines when she decided to sell a major artwork by Roy Lichtenstein to fund a new initiative that aims to end mass incarceration in the United States. A hero to many, she has now been memorialized by her daughter, Catherine Gund, a well-regarded documentary filmmaker who has turned her lens on her mother for a newly released feature-length film. It’s clear that Agnes Gund is a bit of an unwilling subject. Just after the opening credits, Catherine asks Agnes from offscreen, “What do you think of this film?” Agnes replies, “I hope the film will not be seen by too many people.” Unfortunately for Agnes, the film is likely to have widespread appeal, no doubt because of the all-star lineup of interviews it contains, from artists like Julie Mehretu, Teresita Fernández, Glenn Ligon, John Waters, Catherine Opie, as well as Whitney Museum curator Rujeko Hockley, Ford Foundation director Darren Walker, and Thelma Golden, the director and chief curator of the Studio Museum in Harlem. -

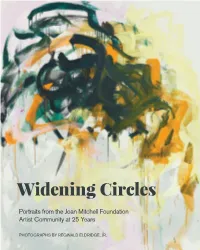

Widening Circles | Photographs by Reginald Eldridge, Jr

JOAN MITCHELL FOUNDATION MITCHELL JOAN WIDENING CIRCLES CIRCLES WIDENING | PHOTOGRAPHS REGINALD BY ELDRIDGE, JR. Widening Circles Portraits from the Joan Mitchell Foundation Artist Community at 25 Years PHOTOGRAPHS BY REGINALD ELDRIDGE, JR. Sonya Kelliher-Combs Shervone Neckles Widening Circles Portraits from the Joan Mitchell Foundation Artist Community at 25 Years PHOTOGRAPHS BY REGINALD ELDRIDGE, JR. Widening Circles: Portraits from the Joan Mitchell Foundation Artist Community at 25 Years © 2018 Joan Mitchell Foundation Cover image: Joan Mitchell, Faded Air II, 1985 Oil on canvas, 102 x 102 in. (259.08 x 259.08 cm) Private collection, © Estate of Joan Mitchell Published on the occasion of the exhibition of the same name at the Joan Mitchell Foundation in New York, December 6, 2018–May 31, 2019 Catalog designed by Melissa Dean, edited by Jenny Gill, with production support by Janice Teran All photos © 2018 Reginald Eldridge, Jr., excluding pages 5 and 7 All artwork pictured is © of the artist Andrea Chung I live my life in widening circles that reach out across the world. I may not complete this last one but I give myself to it. – RAINER MARIA RILKE Throughout her life, poetry was an important source of inspiration and solace to Joan Mitchell. Her mother was a poet, as were many close friends. We know from well-worn books in Mitchell’s library that Rilke was a favorite. Looking at the artist portraits and stories that follow in this book, we at the Foundation also turned to Rilke, a poet known for his letters of advice to a young artist. -

JASON MORAN Born 1975, Houston, TX Lives and Works in New York

JASON MORAN Born 1975, Houston, TX Lives and works in New York, NY HONORS AND AWARDS 2017, Residency, American Academy in Rome 2014-2021, Artistic Director for Jazz, John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington, DC 2011–2013, Artistic Advisor for Jazz, John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington, DC 2010, MacArthur Fellow 2008, US Artists Fellow TEACHING 2010–2016, New England Conservatory of Music, Boston, MA SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 Jason Moran: The Sound Will Tell You, Luhring Augustine Tribeca, New York, NY 2018-2020 Jason Moran, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN; Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, Boston, MA; Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, OH; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY* 2016 Jason Moran: STAGED, Luhring Augustine Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2021 The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA 2020 The Pleasure Pavilion: A Series of Installations, Luhring Augustine Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY * A catalogue was published with this exhibition 2019-2020 Soft Power, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA* 2019 Another Music In a Different Kitchen: Studio Recordings & Records by Artists, Karma Bookstore, New York, NY* 2018-2019 Uptown to Harlem: African American Works from the Collection of Martin and Rebecca Eisenberg, Riverview School, East Sandwich, MA 2018 By the People Festival, National Cathedral, Washington, DC Prospect.4, Algiers Point, New Orleans, LA 2016 Art of Jazz: Form / Performance