Samuel James Cross

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

The Birth of Broadcasting (1961)

This is the first part of a projected three- or four-volume history of broadcasting in the United Kingdom. The whole work is designed as an authoritative account of the rise of broadcasting in England up to the passing of the Independent Television Act in 1955 and the end of the BBC monopoly. Though naturally largely concerned with the BBC, it will be a general history of broadcasting, not simply an institutional history of the BBC, and will briefly sketch the back- ground of wireless developments in other parts of the world. The Birth of Broadcasting covers early amateur experiments in wire- less telephony in America and in England, the pioneer days at Writtle in Essex and elsewhere, and the com- ing of organized broadcasting and its rapid growth during the first four years of the BBC's existence as a private Company before it became a public Corporation in January 1927. Professor Briggs describes how and why the Company was formed, the scope of its activities, and the reasons which led to its conversion from a business enterprise into a national institution. The issues raised between 1923 and 1927 remain pertinent today. The hard bargaining between the Post Office, private wireless interests, and the emergent British Broadcasting Company is discussed in illuminating continued on bock flap $10.00 continued from front flap detail, together with the remarkable opposition with which the Company had to contend in its early days. Many sections of the opposition, including a powerful section of the press, seemed able to conceive of broadcasting only as competing with their own interests, never as comple- menting or enlarging them. -

Edward Taub ADDRESS: Department of Psychology 712 CPM University

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME: Edward Taub ADDRESS: Department of Psychology 712 CPM University of Alabama at Birmingham Birmingham, AL 35294-0018 Tel. No.: (205) 934-2471 Fax: (205) 975-6140 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION: B.A., Brooklyn College M.A., Columbia University Ph.D., New York University HONORS: 2012. The Estabrook Distinguished Research Scientist Award, Kessler Foundation. 2011, B.F. Skinner Lecture, Assoc. for Behavioral Analysis International (ABAI) President – Section J (Psychology), AAAS, 2009 CI therapy named by Soc. Neuroscience as 1 of 10 most exciting current lines of research in neuroscience (2005) Distinguished Scientific Award for the Applications of Psychology of the American Psychological Association (2004) CI therapy named by Soc. Neuroscience as 1 of top 10 Translational Neuroscience Accomplishments of 20th century (2003) Neal Miller Distinguished Research Lecture, American Psychological Association (2003) Leonard Diller Award, Division of Rehabilitation Psychology American Psychological Association (2001) Humboldt Fellow, Germany (2000 - 2005) William James Award, Amer. Psychol. Soc. (1997) Ireland Prize for Scholarly Distinction, Annual Award at Univ. Alabama at Birmingham (1997) Distinguished Scientist of 1996 Award, Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback Scientist of Year Award – National Animal Interest Alliance (1993) Pioneering Research Contributions Award (1989), Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback Distinguished Research Award, Biofeedback Society of America (1988) Guggenheim Fellow (1983-1985) President, Biofeedback Society of America (1978) Fellow, five societies Executive Board, four societies PROFESSIONAL HISTORY: Professor to University Professor, Department of Psychology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1986-present Guest Professor to Standing Guest Professor, University of Konstanz, 1995-2004 1 Guest Professor to Standing Guest Professor, University of Jena, 1996-2004 Visiting Professor - Universities of Tuebingen, Muenster, Hamburg, Humboldt Univ.1993-2002. -

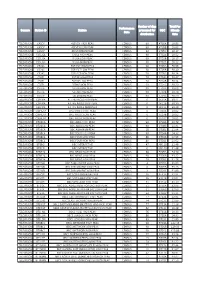

Service Area Categorisation Responsible Unit Expenses Type

Transaction Capital / Service Area Categorisation Responsible Unit Expenses Type Detailed Expenses Type Date Number Amount Revenue SupplierName SupplierID Planning and Development Enterprise projects (inc Market) General Transport Running Expenses MOT 11/04/2018 20282504 55.00 REVENUE 3 H SERVICES (UK) LIMITED 17442 Planning and Development Building Regulations General Transport Running Expenses Servicing/Repairs 11/04/2018 20282504 2,480.85 REVENUE 3 H SERVICES (UK) LIMITED 17442 Planning and Development Building Regulations General Transport Running Expenses MOT 11/04/2018 20282504 55.00 REVENUE 3 H SERVICES (UK) LIMITED 17442 Highways Roads and Transport Car Parks Management General Transport Running Expenses Servicing/Repairs 11/04/2018 20282504 126.06 REVENUE 3 H SERVICES (UK) LIMITED 17442 Environmental Services Pest Control General Transport Running Expenses Servicing/Repairs 11/04/2018 20282504 979.72 REVENUE 3 H SERVICES (UK) LIMITED 17442 Environmental Services Refuse Collection - Domestic General Transport Running Expenses Insurance covered Repairs 11/04/2018 20282504 1,358.03 REVENUE 3 H SERVICES (UK) LIMITED 17442 Environmental Services Refuse Collection - Domestic General Transport Running Expenses Servicing/Repairs 11/04/2018 20282504 9,889.36 REVENUE 3 H SERVICES (UK) LIMITED 17442 Environmental Services Refuse Collection - Domestic General Transport Running Expenses MOT 11/04/2018 20282504 137.00 REVENUE 3 H SERVICES (UK) LIMITED 17442 Environmental Services Refuse Collection - Trade General Transport Running Expenses -

Great Yarmouth and Lowestoft Number: AL100585BA/3 Licensee: Anglian Radio Ltd Contact Name: Daniel Owen, Regulatory Affairs Manager

Analogue Commercial Radio Licence: Format Change Request Form Date of request: 2 September 2019 Station Name: The Beach Licensed area and licence Great Yarmouth and Lowestoft number: AL100585BA/3 Licensee: Anglian Radio Ltd Contact name: Daniel Owen, Regulatory Affairs Manager Details of requested change(s) to Format Character of Service Existing Character of Service: Complete this section if you are requesting a change to this part of your Format Proposed new Character of Service: Programme sharing and/or co- Current arrangements: location arrangements Studio location: Complete this section if you Locally-made programming must be produced are requesting a change to this within the licensed areas of Great Yarmouth & part of your Format Lowestoft (AL100585) or Norwich (AL300). Programme sharing: All programmes may be shared between the Norwich licence (AL300), the North Norfolk licence (AL100586), the Great Yarmouth & Lowestoft licence (AL100585), the Ipswich licence (AL308) and the Tendring licence (AL100128), subject to satisfying the character of service requirements above. Proposed new arrangements: Studio location: Locally-made programming must be produced within the East of England approved area. Programme sharing: All programmes may be shared between the Norwich licence (AL000300), the North Norfolk licence (AL100586), the Great Yarmouth & Lowestoft licence (AL100585) and the Tendring licence (AL100128), subject to satisfying the character of service requirements above. Locally-made hours and/or Current obligations: local news bulletins Locally made hours Complete this section if you At least 7 hours per day during daytime weekdays are requesting a change to this (must include breakfast). part of your Format At least 4 hours daytime Saturdays and Sundays. -

Other Contractor Value for Money Attained in Accordance with The

Vendor Name Payment Date Amount Account Code Description A C LEIGH (NORWICH) LIMITED 01-Jun-2014 644.04 Building - Other Contractor Value for money attained in accordance with the Constabularies Contract Standing Orders A C LEIGH (NORWICH) LIMITED 01-Jun-2014 820.72 Building - Other Contractor Value for money attained in accordance with the Constabularies Contract Standing Orders A C LEIGH (NORWICH) LIMITED 01-Jun-2014 955.14 Building - Other Contractor Value for money attained in accordance with the Constabularies Contract Standing Orders A C LEIGH (NORWICH) LIMITED 01-Jun-2014 1,206.07 Building - Other Contractor Value for money attained in accordance with the Constabularies Contract Standing Orders A C LEIGH (NORWICH) LIMITED 01-Jun-2014 2,805.76 Building - Other Contractor Value for money attained in accordance with the Constabularies Contract Standing Orders A W & D HAMMOND 01-Jun-2014 627.34 Vehicle Repairs & Spares A corporate contract which has been subject to a competitive tender process ABACUS BUILD LIMITED 01-Jun-2014 16,558.05 Building - Main Contractor Value for money attained in accordance with the Constabularies Contract Standing Orders ABSOLUTE APPLICATIONS LIMITED 12-Jun-2014 34,476.00 IT Project Costs Value for money attained in accordance with the Constabularies Contract Standing Orders ABSOLUTE APPLICATIONS LIMITED 19-Jun-2014 1,440.00 IT Project Costs Value for money attained in accordance with the Constabularies Contract Standing Orders ADECCO UK LIMITED 01-Jun-2014 2,075.29 Agency Staff A corporate contract which -

Suffolk Constabulary Expenditure Over £500

Vendor Name Payment Date Amount Account Code Description Value for Money A C HARDING LIMITED 01-Mar-2014 1,521.68 Building - Other Contractor Value for money attained in accordance with the Constabularies Contract Standing Orders A C HARDING LIMITED 01-Mar-2014 14,300.00 Decorating - Planned Value for money attained in accordance with the Constabularies Contract Standing Orders A C LEIGH (NORWICH) LIMITED 01-Mar-2014 1,545.06 Building - Other Contractor Value for money attained in accordance with the Constabularies Contract Standing Orders A C LEIGH (NORWICH) LIMITED 01-Mar-2014 1,581.24 Building - Other Contractor Value for money attained in accordance with the Constabularies Contract Standing Orders ADECCO UK LIMITED 01-Mar-2014 588.47 Agency Staff A corporate contract which has been subject to a competitive tender process ADECCO UK LIMITED 01-Mar-2014 2,596.38 Agency Staff A corporate contract which has been subject to a competitive tender process ADECCO UK LIMITED 01-Mar-2014 590.78 Agency Staff A corporate contract which has been subject to a competitive tender process ALERE TOXICOLOGY 01-Mar-2014 625.00 Operational Equipment Value for money attained in accordance with the Constabularies Contract Standing Orders ALERE TOXICOLOGY 01-Mar-2014 640.00 Operational Equipment Value for money attained in accordance with the Constabularies Contract Standing Orders ANGLIAN PUMPING SERVICES LIMITED 01-Mar-2014 1,083.00 Mechanical Plant - Works Arising Value for money attained in accordance with the Constabularies Contract Standing Orders ANGLIAN -

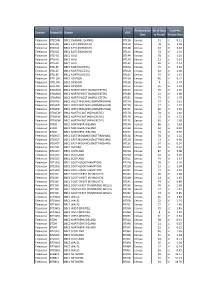

Domain Station ID Station Performance Date Number of Days

Number of days Total Per Performance Domain Station ID Station processed for UDC Minute Date distribution Rate TELEVISION C4SEV 4SEVEN HIGH PEAK CENSUS 90 4T05A £0.86 TELEVISION C4SEV 4SEVEN LOW PEAK CENSUS 90 4T05B £0.62 TELEVISION C4SEV 4SEVEN NON PEAK CENSUS 90 4T05C £0.37 TELEVISION CS5USA 5 USA HIGH PEAK CENSUS 90 5T02A £0.52 TELEVISION CS5USA 5 USA LOW PEAK CENSUS 90 5T02B £0.37 TELEVISION CS5USA 5 USA NON PEAK CENSUS 90 5T02C £0.22 TELEVISION C524S 5SELECT HIGH PEAK CENSUS 90 5T05A £0.56 TELEVISION C524S 5SELECT LOW PEAK CENSUS 90 5T05B £0.40 TELEVISION C524S 5SELECT NON PEAK CENSUS 90 5T05C £0.24 TELEVISION C5SPI 5SPIKE HIGH PEAK CENSUS 90 5T04A £0.47 TELEVISION C5SPI 5SPIKE LOW PEAK CENSUS 90 5T04B £0.34 TELEVISION C5SPI 5SPIKE NON PEAK CENSUS 90 5T04C £0.20 TELEVISION CS5LIF 5STAR HIGH PEAK CENSUS 90 5T03A £0.68 TELEVISION CS5LIF 5STAR LOW PEAK CENSUS 90 5T03B £0.48 TELEVISION CS5LIF 5STAR NON PEAK CENSUS 90 5T03C £0.29 TELEVISION CSATRA AT THE RACES HIGH PEAK CENSUS 0 SK11A £0.41 TELEVISION CSATRA AT THE RACES LOW PEAK CENSUS 0 SK11B £0.30 TELEVISION CSATRA AT THE RACES NON PEAK CENSUS 0 SK11C £0.18 TELEVISION CSB4UM B4U MUSIC HIGH PEAK CENSUS 0 T003A £0.02 TELEVISION CSB4UM B4U MUSIC LOW PEAK CENSUS 0 T003B £0.02 TELEVISION CSB4UM B4U MUSIC NON PEAK CENSUS 0 T003C £0.01 TELEVISION BTBBCA BBC ALBA HIGH PEAK CENSUS 90 BT08A £2.78 TELEVISION BTBBCA BBC ALBA LOW PEAK CENSUS 90 BT08B £1.91 TELEVISION BTBBCA BBC ALBA NON PEAK CENSUS 28 BT08C £1.04 TELEVISION BTBBC4 BBC FOUR HIGH PEAK CENSUS 90 BT04A £4.32 TELEVISION BTBBC4 BBC FOUR -

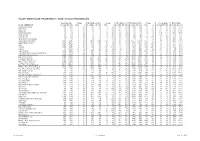

Hallett Arendt Rajar Topline Results - Wave 3 2013/Last Published Data

HALLETT ARENDT RAJAR TOPLINE RESULTS - WAVE 3 2013/LAST PUBLISHED DATA Population 15+ Change Weekly Reach 000's Change Weekly Reach % Total Hours 000's Change Average Hours Market Share LOCAL COMMERCIAL Last PubW3 2013 000's % Last Pub W3 2013 000's % Last PubW3 2013 Last PubW3 2013 000's % Last Pub W3 2013 Last PubW3 2013 Anglian Radio Group 1003 1002 -1 0% 230 226 -4 -2% 23% 23% 1867 1826 -41 -2% 8.1 8.1 8.2% 8.2% THE BEACH 182 182 0 0% 58 55 -3 -5% 32% 30% 478 460 -18 -4% 8.2 8.3 12.7% 11.8% Dream 100 134 134 0 0% 40 42 2 5% 30% 31% 441 459 18 4% 11.1 11.0 12.9% 13.7% North Norfolk Radio 93 93 0 0% 21 21 0 0% 23% 23% 233 243 10 4% 11.0 11.6 10.5% 10.7% Norwich 99.9fm 328 328 0 0% 48 48 0 0% 15% 15% 306 308 2 1% 6.3 6.4 4.2% 4.4% Town 102 FM 289 289 0 0% 64 61 -3 -5% 22% 21% 410 357 -53 -13% 6.4 5.9 6.2% 5.5% 107.8 Arrow FM for Hastings 118 119 1 1% 20 21 1 5% 17% 17% 171 179 8 5% 8.5 8.6 6.0% 6.0% Bauer Radio Total Portfolio 53205 53205 0 0% 14045 14304 259 2% 26% 27% 112551 113703 1152 1% 8.0 7.9 10.9% 11.0% Bauer Passion Portfolio 53205 53205 0 0% 7568 7590 22 0% 14% 14% 47582 46047 -1535 -3% 6.3 6.1 4.6% 4.5% Heat 53205 53205 0 0% 790 758 -32 -4% 1% 1% 2834 2543 -291 -10% 3.6 3.4 0.3% 0.2% The Hits 53205 53205 0 0% 984 875 -109 -11% 2% 2% 3419 2671 -748 -22% 3.5 3.1 0.3% 0.3% Kisstory n/p 53205 n/a n/a n/p 854 n/a n/a n/p 2% n/p 3296 n/a n/a n/p 3.9 n/p 0.3% Planet Rock UK 53205 53205 0 0% 1296 1191 -105 -8% 2% 2% 9945 8695 -1250 -13% 7.7 7.3 1.0% 0.8% Planet Rock 105.2 (formerly Kerrang! 105.2) 3672 3673 1 0% 305 287 -18 -6% 8% -

QUARTERLY SUMMARY of RADIO LISTENING Survey Period Ending 3Rd April 2016

QUARTERLY SUMMARY OF RADIO LISTENING Survey Period Ending 3rd April 2016 PART 1 - UNITED KINGDOM (INCLUDING CHANNEL ISLANDS AND ISLE OF MAN) Adults aged 15 and over: population 53,575,000 Survey Weekly Reach Average Hours Total Hours Share in Period '000 % per head per listener '000 TSA % All Radio Q 47823 89 18.8 21.0 1006462 100.0 All BBC Radio Q 34869 65 10.2 15.6 544682 54.1 All BBC Radio 15-44 Q 14423 57 5.8 10.2 147513 39.1 All BBC Radio 45+ Q 20446 72 14.1 19.4 397169 63.1 All BBC Network Radio1 Q 32014 60 8.8 14.7 469102 46.6 BBC Local Radio Q 8793 16 1.4 8.6 75580 7.5 All Commercial Radio Q 34277 64 8.1 12.7 434436 43.2 All Commercial Radio 15-44 Q 18057 71 8.6 12.0 217166 57.5 All Commercial Radio 45+ Q 16221 57 7.7 13.4 217270 34.5 All National Commercial1 Q 18220 34 2.7 8.1 147175 14.6 All Local Commercial (National TSA) Q 26884 50 5.4 10.7 287261 28.5 Other Radio Q 3816 7 0.5 7.2 27344 2.7 Source: RAJAR/Ipsos MORI/RSMB 1 See note on back cover. For survey periods and other definitions please see back cover. Please note that the information contained within this quarterly data release has yet to be announced or otherwise made public Embargoed until 00.01 am and as such could constitute relevant information for the purposes of section 118 of FSMA and non-public price sensitive 19th May 2016 information for the purposes of the Criminal Justice Act 1993. -

Broadcast Website Info D183 MCPS.Xlsx

Performance No of Days Total Per Domain Station IDStation UDC Date in Period Minute Rate Television BT1CHN BBC1 CHANNEL ISLANDS BT11A Census 51£ 0.11 Television BT1EAS BBC1 EAST (NORWICH) BT12A Census 78£ 3.04 Television BT1EAS BBC1 EAST (NORWICH) BT12B Census 13£ 2.18 Television BT1EAS BBC1 EAST (NORWICH) BT12C Census 74£ 1.31 TelevisionBT1HUL BBC1 HULL BT14A Census 78£ 0.33 TelevisionBT1HUL BBC1 HULL BT14B Census 13£ 0.24 TelevisionBT1HUL BBC1 HULL BT14C Census 65£ 0.14 Television BT1LEE BBC1 NORTH (LEEDS) BT16A Census 77£ 3.32 Television BT1LEE BBC1 NORTH (LEEDS) BT16B Census 12£ 2.38 Television BT1LEE BBC1 NORTH (LEEDS) BT16C Census 74£ 1.42 Television BT1LON BBC1 LONDON BT15A Census 46£ 5.22 Television BT1LON BBC1 LONDON BT15B Census 4£ 3.74 Television BT1LON BBC1 LONDON BT15C Census 65£ 2.24 Television BT1MAN BBC1 NORTH WEST (MANCHESTER) BT18A Census 78£ 4.16 Television BT1MAN BBC1 NORTH WEST (MANCHESTER) BT18B Census 13£ 2.98 Television BT1MAN BBC1 NORTH WEST (MANCHESTER) BT18C Census 73£ 1.79 Television BT1MID BBC1 WEST MIDLANDS (BIRMINGHAM) BT27A Census 74£ 3.23 Television BT1MID BBC1 WEST MIDLANDS (BIRMINGHAM) BT27B Census 12£ 2.32 Television BT1MID BBC1 WEST MIDLANDS (BIRMINGHAM) BT27C Census 60£ 1.39 Television BT1NEW BBC1 NORTH EAST (NEWCASTLE) BT17A Census 78£ 2.40 Television BT1NEW BBC1 NORTH EAST (NEWCASTLE) BT17B Census 13£ 1.72 Television BT1NEW BBC1 NORTH EAST (NEWCASTLE) BT17C Census 65£ 1.03 Television BT1NI BBC1 NORTHERN IRELAND BT19A Census 86£ 1.29 Television BT1NI BBC1 NORTHERN IRELAND BT19B Census 33£ 0.92 Television -

Radio Norwich

Analogue Commercial Radio Licence: Format Change Request Form Date of request: 25 March 2020 Station Name: Radio Norwich Licensed area and licence Norwich number: AL102318 Licensee: Anglian Radio Ltd Contact name: Graham Bryce Details of requested change(s) to Format Character of Service Existing Character of Service: Complete this section if you are requesting a change to this part of your Format Proposed new Character of Service: Programme sharing and/or co- Current arrangements: location arrangements Programme sharing: All programmes may be shared between the Complete this section if you are Norwich licence (AL300), the North Norfolk licence requesting a change to this (AL100586), the Great Yarmouth & Lowestoft part of your Format licence (AL100585), and the Tendring licence (AL100128), subject to satisfying the character of service requirements above Co-location arrangements: Locally-made programming must be produced within the approved area of the East of England. Proposed new arrangements: Programme sharing: All programmes may be shared between the Norwich licence (AL300), the North Norfolk licence (AL100586), the Great Yarmouth & Lowestoft licence (AL100585),the Kings Lynn licence (AL134) and the Tendring licence (AL100128), subject to satisfying the character of service requirements above. Locally-made hours and/or Current obligations: local news bulletins Complete this section if you are requesting a change to this part of your Format Proposed new obligations: The holder of an analogue local commercial radio licence may apply