Towards a Tension-Based Definition of Digital Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origins of Electronic Literature. an Overview. As Origens Da Literatura Eletrônica

Texto Digital, Florianópolis, v. 15, n. 1, p. 4-27, jan./jun. 2019. https://doi.org/10.5007/1807-9288.2019v15n1p4 The Origins of Electronic Literature. An Overview. As origens da Literatura Eletrônica. Um panorama. Giovanna Di Rosarioa; Kerri Grimaldib; Nohelia Mezac a Politecnico di Milano, Milano, Italy - [email protected] b Hamilton College, Clinton, New York United States of America - [email protected] c University of Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom - [email protected] Keywords: Abstract: The aim of this article is to sketch the origins of electronic literature and to Electronic highlight some important moments in order to trace its history. In doing so we consider Literature. Origins. the variety of languages, cultural backgrounds, cultural heritages, and contexts in which Development. digital literature has been created. The article is divided into five sections: a brief World. history of electronic literature in general (however, we must admit that this section has a very ethnocentric point of view) and then four other sections divided into North American, Latin American, European (Russia included), and Arab Electronic Literature. Due to the lack of information, there is no section devoted to Electronic Literature in Asia, although a few texts will be mentioned. We are aware of the limits of this division and of the problems it can create, however, we thought it was the easiest way to shortly map out the origins of electronic literature and its development in different countries and continents. The article shows how some countries have developed their interest in and creation of electronic literature almost simultaneously, while others, just because of their own cultural background and/or contexts (also political and economic contexts and backgrounds), have only recently discovered electronic literature, or accepted it as a new form of the literary genre. -

Sue Thomas, Phd [email protected]

CURRICULUM VITAE last updated June 2013 Sue Thomas, PhD www.suethomas.net [email protected] Narrative Summary I have been writing about computers and the internet since the late 1980s. My books include ‘Technobiophilia: nature and cyberspace (2013), a study of the biophilic relationship between nature and technology, Hello World: travels in virtuality (2004), a travelogue/memoir of life online, and Correspondence (1992), short-listed for the Arthur C. Clarke Award for Best Science Fiction Novel. In 1995 I found the pioneering trAce Online Writing Centre, an early global online community based at Nottingham Trent University which ran for ten years. From 2005-2013 I was Professor of New Media in the Institute of Creative Technologies at De Montfort University where I researched biophilia, social media, transliteracy, transdisciplinarity and future foresight, as well as running innovative projects like the NESTA-funded Amplified Leicester, and the development of the DMU Transdisciplinary Common Room, a collaborative space for cross-faculty working. To date I have received funding from Arts Council England, the Arts and Humanities Research Board, the British Academy, the British Council, the EU, the Higher Education Innovation Fund, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, NESTA and many others. My partners have included commercial companies, universities, arts organisations, local authorities and colleagues in Sweden, Finland, France, Australia and the USA. I left De Montfort University in June 2013 to focus on writing and consultancy and I am currently researching future forecasting in nature, technology and well-being. I want to know what practical steps we might take to ensure that our digital lives are healthy, mindful and productive. -

Learning As You Go: Inventing Pedagogies for Electronic Literature

Learning as you go: Inventing Pedagogies for Electronic Literature. In a field like electronic literature, which is both well developed and always emerging, most teachers have faced the challenge of teaching material that is regarded as “marginal” within the Humanities but relevant in the classroom. Though the scholars that circulate around the organization tend to be very interested in literary approaches, most have found themselves working in roundabout ways, slipping electronic literature into literature surveys, media studies, fine arts, and computer science classrooms. Indeed, as Maria Engberg notes in her survey of electronic literature pedagogy in Europe, there are a range of institutional obstacles to the teaching of electronic literature, and these obstacles differ depending on national, institutional, and disciplinary contexts. Citing Jorgen Schafer’s experience teaching eliterature in Germany, Engberg points to the various places where electronic literature can fit into a broader curriculum: “1) literary studies; 2) communications or media studies; 3) art and design schools or creative writing programs; and 4) computer science departments.”i In response to the scant attention to electronic literature in German academic settings, Shafer’s recommendation is “to ‘reanimate’ the so-called Allgemeine Literaturwissenschaft (or ‘general study of literature’) of the 1970s and 1980s in German universities.”ii The conclusion reflected broadly across the various approaches in Engberg’s survey is that the electronic literature teacher must -

10 Gaps for Digital Literature? Serge Bouchardon

Mind the gap! 10 gaps for Digital Literature? Serge Bouchardon ELO Montreal Conference (keynote), 17/08/18: http://www.elo2018.org/ Introduction 2 1. The Field of Digital Literature 3 1.1. Gap No.1 3 Creation: From Building Interfaces to Using Existing Platforms? 1.2. Gap No.2 6 Audience: From a Private to a Mainstream Audience? 1.3. Gap No.3 7 Translation: from Global Digital Cultural Homogeneity to Cultural Specificities? 1.4. Gap No.4 8 The Literary Field: From Literariness to Literary Experience? 2. The Reading Experience 10 2.1. Gap No.5 10 Gestures: From Reading Texts to Interpretation through Gestures? 2.2. Gap No.6 11 Narrative : From Telling a Story to Mixing Fiction with the Reader’s Reality? 2.3. Gap No.7 14 The Digital Subject: From Narrative Identity to Poetic Identity? 3. Teaching and Research 16 3.1. Gap No.8 16 Pedagogy: From Literacy to Digital Literacy? 3.2. Gap No.9 19 Preservation: From a Model of Stored Memory to a Model of Reinvented Memory? 3.3. Gap No.10 23 Research: From an Epistemology of Measure to an Epistemology of Data? Conclusion 25 Bibliography 26 1 Introduction What exactly do we mean by digital literature? This field has existed for over six decades, descending from clearly identified lineages (combinatorial writing and constrained writing, fragmentary writing, sound and visual writing…). The terminology varies, and digital, electronic, and computer-based literature are all commonly used. Yet most critics in the field are in agreement on the distinction between the two principal forms of literature relying on digital media: digitized literature and true digital literature (even if the boundary between the two is sometimes rather blurred, perhaps increasingly so). -

The Emergence of Cyber Literature: a Challenge to Teach Literature from Text to Hypertext

Proceedings | “Netizens of the World #NOW: Elevating Critical Thinking through Language and Literature” | ISBN 978-602-50956-4-1 THE EMERGENCE OF CYBER LITERATURE: A CHALLENGE TO TEACH LITERATURE FROM TEXT TO HYPERTEXT Deri Sis Nanda [email protected] Susanto Susanto [email protected] Bandar Lampung University, Indonesia Abstract In a digital era, people live in a cyberspace that they become part of modern society. The information that they have acquired is from the World Wide Web (WWW). This WWW has become an important medium for people in the world to disseminate information. Because of the technology of Web, cyber literature emerges. This study talks about the emergence of cyber literature which changes the way of reading and teaching in various institutions. It becomes a challenge for people who teach literature because they should leave the printed text and move to the digital text as called hypertext. The existence of cyber literature also drives them change their style to analyze and criticize the work of literature. So, it becomes a challenge for them to teach literature from text to hypertext. Keywords: cyber literature, emergence, text, hypertext, cyberspace, challenge, development. Introduction The influence of technology changes all aspects of people’s lives in the world. They become modern society who always get information and do communication in a virtual space. The influence can be seen in work places, homes and teaching institutions. Most of them acquire the information from the World Wide Web (WWW). It is a space for the users to read, write, and access the information with devices connected with the internet. -

Electronic Literature in Ireland

Electronic Literature in Ireland James O’Sullivan Published in the Electronic Book Review at: https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/electronic-literature-in-ireland/ Licensed under: Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License *** Literary Ireland has long embraced experimentation.1 So, in an artistic community that typically gravitates towards the new, it is culturally anomalous to see that electronic literature2 has failed to flourish. Ireland, sitting at the nexus between the North American and European e-lit communities, should be playing a more active role in what is becoming an increasingly significant literary movement. This article provides a much needed account of the field of electronic literature as it exists at present within an Irish context, simultaneously exploring those circumstances which have contributed to its successes and failures. Doing so rectifies a major gap in the national media archaeologies of this field, presenting an incomplete yet untold culturally specific literary history. While a complete literary history of Ireland’s e-lit community3 cannot be accomplished within the constraints of this single essay—there will inevitably be limitations in scope, practitioners I have failed to acknowledge, writings I have missed in my review—what can be achieved here is the beginning of a discourse which will hopefully flourish in years to come. Electronic Literature as Community What makes for a literary movement? In many respects, literary movements are, like any cohort, little more than the coming together of like-minded individuals who share a common interest in a particular ideology or practice—communities are about a shared culture, some elusive thing that binds. -

Teaching Digital Literature

Roberto Simanowski Teaching Digital Literature Didactic and Institutional Aspects 1 Making Students Fit for the 21st Century When Nam Jun Paik in the last two decades of the 20th century created video installations confronting the audience with multiple screens which the specta- tor had to follow by simultaneously jumping from one to another while scan- ning them all for information, Paik was training his audience for the tasks of the 21st century. With this notion, Janez Strehovec situates our topic within the broader cultural and social context of new media that redefine the areas of economy, sciences, education, and art, stressing the importance of new media literacy in contemporary society. Such literacy not only consists of the ability to read, write, navigate, alter, download and ideally program web documents (i.e., reading non-linear structures, being able to orient oneself within a labyrinthic environment). It also includes the ability to identify with the cursor, the avatar and with virtual space, to travel in spatially and temporally compressed units without physical motion, to carry out real-time activities, and to undertake as- sociative selection, sampling and reconfiguration resembling DJ and VJ cul- ture. In Strehovec’s perspective (in his essay in Part One), the stakes are very high. The aesthetics of the Web teaches the logic of contemporary culture but also the needs of contemporary multicultural society. The mosaic structure of a web site with documents of divergent origin each with its own particular iden- tity and time, the simultaneity of divergent documents, artifacts, and media teaches us, according to Strehovec, to live with the coexistence of conflicting concepts, discourses, and cultures. -

Towards a History of Electronic Literature

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 16 (2014) Issue 5 Article 2 Towards a History of Electronic Literature Urszula Pawlicka University of Warmińsko-Mazurski Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, and the Other Arts and Humanities Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Pawlicka, Urszula. "Towards a History of Electronic Literature." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 16.5 (2014): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.2619> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 1359 times as of 11/ 07/19. -

The Origins of Electronic Literature: an Overview." Electronic Literature As Digital Humanities: Contexts, Forms, & Practices

Rosario, Giovanna di, Nohelia Meza, and Kerri Grimaldi. "The Origins of Electronic Literature: An Overview." Electronic Literature as Digital Humanities: Contexts, Forms, & Practices. By James O’Sullivan. New York,: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021. 9–26. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 28 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501363474.ch-001>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 28 September 2021, 19:33 UTC. Copyright © Volume Editor’s Part of the Work © Dene Grigar and James O’Sullivan and Each chapter © of Contributors 2021. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 1 The Origins of Electronic Literature: An Overview Giovanna di Rosario, Nohelia Meza, and Kerri Grimaldi The aim of this chapter is to sketch the origins of electronic literature and to highlight some important moments in order to trace its history. As electronic literature is a “recent” form of literature (Hayles) one could suppose that it is an easy duty to look for its origins. However, due to its ephemeral nature—many of the electronic literature works created in the last century and even in this one are lost or they do not work anymore on modern computers due to the inevitable mutation of technology—which makes the goal more complex than one may think. Electronic literature is a form of literature that started to appear with the advent of computers and digital technology. It is a digital-oriented literature, but the reader should not confuse it with digitized print literature. -

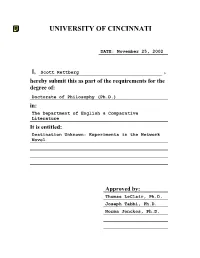

Destination Unknown: Experiments in the Network Novel

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: November 25, 2002 I, Scott Rettberg , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in: The Department of English & Comparative Literature It is entitled: Destination Unknown: Experiments in the Network Novel Approved by: Thomas LeClair, Ph.D. Joseph Tabbi, Ph.D. Norma Jenckes, Ph.D. Destination Unknown: Experiments in the Network Novel A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences 2003 by Scott Rettberg B.A. Coe College, 1992 M.A. Illinois State University, 1995 Committee Chair: Thomas LeClair, Ph.D. Abstract The dissertation contains two components: a critical component that examines recent experiments in writing literature specifically for the electronic media, and a creative component that includes selections from The Unknown, the hypertext novel I coauthored with William Gillespie and Dirk Stratton. In the critical component of the dissertation, I argue that the network must be understood as a writing and reading environment distinct from both print and from discrete computer applications. In the introduction, I situate recent network literature within the context of electronic literature produced prior to the launch of the World Wide Web, establish the current range of experiments in electronic literature, and explore some of the advantages and disadvantages of writing and publishing literature for the network. In the second chapter, I examine the development of the book as a technology, analyze “electronic book” distribution models, and establish the difference between the “electronic book” and “electronic literature.” In the third chapter, I interrogate the ideas of linking, nonlinearity, and referentiality. -

Of Electronic Literature PDF Ebook

2015: The End(s) of Electronic Literature 2015: The End(s) of Electronic Literature Electronic Literature Organization Conference Program and Festival Catalog Editors: Anne Karhio, Lucas Ramada Prieto, Scott Rettberg ELMCIP, University of Bergen Dept. of Linguistic, Literary, and Aesthetic Studies, P.O. Box 7805, University of Bergen, 5020 Bergen, Norway. Published in 2015 by ELMCIP with the support of the Irish Research Council and the European Commission. This work ELO 2015: The End(s) of Electronic Literature is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Public License (CC-BY-NC 4.0). ISBN-13 ELO 2015: The End(s) of Electronic Literature (pbk)—ISBN 978-82-999089-6-2 (EPUB)—ISBN 978-82-999089-7-9 (PDF)—ISBN 978-82-999089-8-6 Printed in Ireland at National University of Ireland Galway. Cover and ELO 2015 identity by Talan Memmott. iv Contents Introduction: The End(s) of Electronic Literature Scott Rettberg (University of Bergen) 1 ELO 2015 Conference Organizations Committee Membership 6 ELO 2015 Conference Schedule Events by date and time 8 Keynote Debate: End over End Espen Aarseth and Stuart Moulthrop 17 WORKSHOPS 19 History of Digital Poetry in France Conveners: Philippe Bootz (Université Paris 8) and Johnathan Baillehache (University of Georgia) 21 Multimedia Authoring in Scalar Convener: Samantha Gorman (University of Southern California) 21 Sonic Sculpture Convener: Taras Mashtalir (Independent) 21 Documenting Events and Works in the ELMCIP Electronic Literature Knowledge Base Conveners: Scott Rettberg, Álvaro Seiça and Patricia Tomaszek (University of Bergen) 22 Live Writing Convener: Otso Huopaniemi (University of Arts, Helsinki) 23 Digital Scherenschnitte / Video Compositing with Cut-ups and Collage Conveners: Alison Aune and Joellyn Rock (University of Minnesota— Duluth) 23 Revisiting the Spam Folder: Using 419-fiction for Interactive Storytelling. -

Of Electronic Literature John Cayley, Brown University, Literary Arts

Aurature at the End(s) of Electronic Literature John Cayley, Brown University, Literary Arts Means and ends. Within the very phrase ‘electronic literature’ its ends are implicated in its means. ‘Electronic’ refers to means in a way that is well understood but promotes quite specific means as the essential attribute of a cultural phenomenon, a phenomenon that was once new, a new kind of literature, a new teleology for literary practice, an ‘end’ of literature having its own ends, the end of electronic literature in its means, ends justified by means. This brief essay will not remain bound up within the conceptual entanglements of a name.1 We will move on from ‘end(s)’ to means, to media, and finally — as we shall see — to medium.2 We understand that ‘electronic’ in ‘electronic literature’ — now indisputably one end of a field of serious play for the theory and practice of literature — refers metonymically to computation and all its infrastructure: hardware, software, interface & interaction design, networking, and today also, since at least the mid 2000s, to a particular de facto historically-created world built from all of this infrastructure within which most of us now ‘live’ for a considerable portion of our lives, our cultural and, predominantly, our commercially implicated, transactional lives. The existence of a particular world, or, to use a less charitable if more accurately constrained term, a regime of computation is worth recalling as we establish some 1 I have discussed problems with the terminology of digitally mediated literary practice in a previous contribution, fully published here: Cayley, J.