Pitfalls at Globe 1990

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TREFOR PROUD Make-Up Artist IATSE 706 Journeyman Member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

TREFOR PROUD Make-Up Artist IATSE 706 Journeyman Member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences FILM MR. CHURCH Make-Up Department Head Director: Bruce Beresford Cast: Britt Robertson, Xavier Samuel, Christian Madsen SPY Make-Up Department Head Director: Paul Feig Cast: Jason Statham, Rose Byrme, Peter Serafinowicz, Julian Miller THE PURGE 2 - ANARCHY Make-Up Department Head and Mask Design Director: James DeMonaco Cast: Michael K. Williams, Frank Grillo, Carmen Ejogo BONNIE AND CLYDE Make-Up Department Head Director: Bruce Beresford Cast: Emile Hirsch, Holly Hunter, William Hurt, Sarah Hyland Nominee: Emmy – Outstanding Make-Up for a Miniseries or a Movie (Non-Prosthetic) ENDER’S GAME Make-Up Department Head Director: Gavin Hood Cast: Harrison Ford, Asa Butterfield, Sir Ben Kingsley JACK REACHER Make-Up Department Head Director: Christopher McQuarrie Cast: Rosamund Pike, Robert Duvall THE RITE Make-Up and Hair Designer Director: Mikael Håfström Cast: Alice Braga, Anthony Hopkins, Ciarán Hinds A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET Department Head Make-Up, Los Angeles Director: Samuel Bayer Cast: Jackie Earle Hayley, Kyle Gallner, Rooney Mara, Katie Cassidy, Thomas Dekker, Kellan Lutz, Clancy Brown LONDON DREAMS Make-Up and Hair Designer Director: Vipul Amrutlal Shah Cast: Salman Khan, Ajay Devgan, Asin, THE COURAGEOUS HEART Make-Up and Hair Department Head OF IRENA SENDLER Director: John Kent Harrison Hallmark Hall of Fame Cast: Anna Paquin, Goran Visnjic, Marcia Gay Harden Winner: Emmy for Outstanding Make-Up for a Miniseries or Movie -

Larry D. Horricks Society of Motion Picture Stills Photographers

Larry D. Horricks Society of Motion Picture Stills Photographers www.larryhorricks.com Feature Films: Spaceman of Bohemia – Netflix – Johan Renck Director Cast – Adam Sandler, Carey Mulligan Producers: Michael Parets, Max Silva, Ben Ormand, Barry Bernardi White Bird – Lionsgate – Marc Forster Director (Unit + Specials_ Cast: Gillian Anderson ,Helen Mirren, Ariella Glaser, Orlando Schwerdt Producers: Marc Forster, Tod Leiberman, David Hoberman, Raquel J. Palacio Oslo – Dreamworks Pictures / Amblin / HBO / Marc Platt Prods.– Bart Sher Director (Unit + Specials) Cast: Ruth Wilson, Andrew Scott, Jeff Wilbusch,Salim Dau, Producers: Steven Spielberg, Kristie Macosko Krieger, Marc Platt, Cambra Overend, Mark Taylor Atlantic 437 – Netflix. Ratpack Entertainment – Director Peter Thorwath Producers: Chritian Becker,Benjamin Munz The Dig – Netflix, Magnolia Mae Films – Simon Stone Director Cast: Ralph Fiennes, Carey Mulligan, Lily James, Ken Stott, Johnny Flynn Producers: Gabrielle Tana, Carolyn Marks Blackwood, Redmond Morris A Boy Called Christmas – Netflix – Gil Kenan Director (Unit + Specials) Cast: Sally Hawkins, Kristen Wiig,Maggie Smith, Jim Broadbent, Toby Jones, Michiel Huisman, Harry Lawful Producers: Graham Broadbent, Pete Czernin, Kevan Van Thompson Minamata - Metalwork Pictures /HanWay Films / MGM - Andrew Levitas Director (Unit + Specials) Cast: Johnny Depp, Bill Nighy, Minami, Hiro Sanada, Ryo Kase, Sato Tadenobu, Jun Kunimura Producers: Andrew Levitas,Gabrielle Tana, Jason Foreman, Johnny Depp, Sam Sarkar, Stephen Deuters, Kevan -

Konstantinos Kavakiotis

KONSTANTINOS KAVAKIOTIS Tel: 0044 7515017485 or 00306972 006 991 Email: [email protected] Website: www.kavakiotis.com Personal Details Spotlight: View Pin - 1173-5611-6071 Height: 6' (183cm) Eyes: Brown Hair: Black Training Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, International Actors Fellowship Directors Lab, Lincoln Center Theatre New York Steppenwolf Company, Los Angeles Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, London: MA Classical Acting (Distinction) Moscow Art Theatre Summer School Drama Studio of Thessaloniki Mime course at Montpellier with Outil Theatre Workshop with the Movement Director of the Royal Shakespeare Company, Anna Morissey ‘Renaissance Gestures’ Workshop with Patrick Tucker, ‘Secrets of Acting Shakespeare’ Workshop with Peter Hall, ‘Shakespeare Advice for the Players’ Masterclass with James Purefoy, ‘Shakespeare’s King Lear’ Professional Experience 2019, Film, Badnaam, Faizal Baghdadi, Krishna Bhatt, (India- U.K.) 2018, Television, Fadi Fawaz, George Michael’s Docudrama, ITV- REELZ (U.K.- U.S.A) 2018, Stage, Man, The Open Couple, Hannah Quigley (Etcetera Theatre London-UK) 2017, Stage, King Herod, Salome, Anastasia Revi (Hoxton Hall-London, Avignon Festival- France, Athens-Greece) 2016, Stage, Macbeth, Macbeth, Anastasia Revi, National Theatre of Greece (Thessaloniki-Greece) 2016, Stage, Eric Brun, Dancing With The Devil, Anastasia Revi, (Sadler’s Wells Theatre, London- UK) 2015, Commercial, Arab Husband, Dulux (London-U.K.) 2014, Short-Film, Man, Night Hunter, Michael Hapeshi (London-U.K.) 2013, Short-Film, George, Don’t Call -

MARK HOLDING - Sound Mixer

MARK HOLDING - Sound Mixer WONDERWELL Director: Vlad Marsavin. Producer: Richard Schlesinger. Starring: Keira Millard, Carrie Fisher and Lloyd Owen. Strange Quark Films. BLACK SAILS (Series 4) Directors: Lukas Ettlin, Alik Sakharov and Roel Reine. Producers: Nina Heyns and Dan Shotz. Starring: Zach McGowan, Toby Stephens, Luke Arnold and Jessica Parker Kennedy. Starz / Film Afrika Worldwide. TUT Director: David Von Ancken. Producer: Guy J. Louthan. Starring: Ben Kingsley and Avan Jogia. Muse Entertainment. TRANSPORTER (Series 2) Directors: Eric Vallete, Stefan Pleszczynski and PJ Pesce. Producer: Marc Jenny. Starring: Chris Vance and Violante Placido. Atlantique Productions. THE MUSKETEERS Directors: Toby Haynes, Richard Clark, Farren Blackburn, Andy Hay and Saul Metzstein. Producer: Colin Wratten. Starring: Tom Burke, Santiago Cabrera, Peter Capaldi, Tamla Kari, Maimie McCoy, Luke Pasqualino and Hugo Speer. BBC America. THE LAST KNIGHTS Director: Kazuaki Kiriya. Producer: Luci Y. Kim. Starring: Morgan Freeman, Clive Owen, Cliff Curtis, Ayelet Zuret and Shohreh Aghdashloo. Czech Anglo Productions / Luka Productions International. 4929 Wilshire Blvd., Ste. 259 Los Angeles, CA 90010 ph 323.782.1854 fx 323.345.5690 [email protected] 300: BATTLE OF ARTEMISIA Director: Noam Murro. Producers: Zack Snyder, Mark Canton, Bernie Goldman, Gianni Nunnari, Deborah Snyder and Thomas Tull. Starring: Eva Green, Rodrigo Santoro, Jack O’Connell, Sullivan Stapleton and Andrew Tiernan. Atmosphere Entertainment. SNOWPIERCER Director: Joon-ho Bong. Producer: Chan-wook Park. Starring: Chris Evans, Jamie Bell, Octavia Spencer, Tilda Swinton, John Hurt and Alison Pill. Moho Films. MISSING Director: Steve Shill. Producer: David Minkowski. Starring: Sean Bean, Ashley Judd and Cliff Curtis. ABC Studios / Little Engine Productions / Stillking Films. -

Movie Data Analysis.Pdf

FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM COGS108 Final Project Group Members: Yanyi Wang Ziwen Zeng Lingfei Lu Yuhan Wang Yuqing Deng Introduction and Background Movie revenue is one of the most important measure of good and bad movies. Revenue is also the most important and intuitionistic feedback to producers, directors and actors. Therefore it is worth for us to put effort on analyzing what factors correlate to revenue, so that producers, directors and actors know how to get higher revenue on next movie by focusing on most correlated factors. Our project focuses on anaylzing all kinds of factors that correlated to revenue, for example, genres, elements in the movie, popularity, release month, runtime, vote average, vote count on website and cast etc. After analysis, we can clearly know what are the crucial factors to a movie's revenue and our analysis can be used as a guide for people shooting movies who want to earn higher renveue for their next movie. They can focus on those most correlated factors, for example, shooting specific genre and hire some actors who have higher average revenue. Reasrch Question: Various factors blend together to create a high revenue for movie, but what are the most important aspect contribute to higher revenue? What aspects should people put more effort on and what factors should people focus on when they try to higher the revenue of a movie? http://localhost:8888/nbconvert/html/Desktop/MyProjects/Pr_085/FinalProject.ipynb?download=false Page 1 of 62 FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM Hypothesis: We predict that the following factors contribute the most to movie revenue. -

James Purefoy Is a Boyhood Football Team, Yeovil Town

LOGS, PIGS and yoyos! yoyo. “Yes,” he laughs. “I could do likes of Sean Bean, Reece With- By MARTIN MCCONACHIE amazing tricks with a yoyo; certainly erspoon, Kevin McKidd and Neve the most talent I’ve had in sport and Campbell. His CV contains HBO/ AVING already revealed I tried to amuse the more anxious BBC series Rome; other TV series that we have award-win- patients in my care as I wheeled them such as Sharpe’s Sword, The Mayor ning comedian Diane down to surgery. I had a great time of Casterbridge and Beau Brummel: Spencer as a Yeovil fan, there and met some strong, interest- This Charming Man and fi lms like it gives us great pleasure H ing people during my formative years The Knights Tale, Resident Evil and to also inform you that we’ve found after being in a public school for ten Solomon Kane. another celebrity Glover, actor James years.” Next up for the Glovers nut is Purefoy. Another growing love was for his a Disney Pixar production set on At fi rst glance, James Purefoy is a boyhood football team, Yeovil Town. Mars called John Carter which is familiar face but one that you can’t “I started going to games when I was set to be released in the United immediately tag to one series. His about the same age as my nephew Kingdom in March and will hopefully acting CV runs to almost 25 years, whose here with me today, about lead to more TV and fi lm parts impressive longevity in a ruthless seven or eight. -

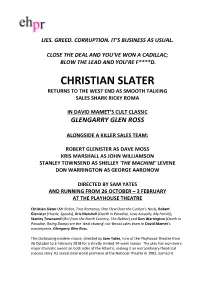

Christian Slater Returns to the West End As Smooth Talking Sales Shark Ricky Roma

LIES. GREED. CORRUPTION. IT’S BUSINESS AS USUAL. CLOSE THE DEAL AND YOU'VE WON A CADILLAC; BLOW THE LEAD AND YOU'RE F****D. CHRISTIAN SLATER RETURNS TO THE WEST END AS SMOOTH TALKING SALES SHARK RICKY ROMA IN DAVID MAMET’S CULT CLASSIC GLENGARRY GLEN ROSS ALONGSIDE A KILLER SALES TEAM: ROBERT GLENISTER AS DAVE MOSS KRIS MARSHALL AS JOHN WILLIAMSON STANLEY TOWNSEND AS SHELLEY 'THE MACHINE' LEVENE DON WARRINGTON AS GEORGE AARONOW DIRECTED BY SAM YATES AND RUNNING FROM 26 OCTOBER – 3 FEBRUARY AT THE PLAYHOUSE THEATRE Christian Slater (Mr Robot, True Romance, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest), Robert Glenister (Hustle, Spooks), Kris Marshall (Death in Paradise, Love Actually, My Family), Stanley Townsend (Girl From the North Country, The Nether) and Don Warrington (Death in Paradise, RisinG Damp) are the ‘deal chasing’ cut-throat sales team in David Mamet’s masterpiece, Glengarry Glen Ross. This trailblazing modern classic, directed by Sam Yates, runs at the Playhouse Theatre from 26 October to 3 February 2018 for a strictly limited 14-week season. The play has won every major dramatic award on both sides of the Atlantic, making it an extraordinary theatrical success story. Its sensational world premiere at the National Theatre in 1983, earned it the Olivier Award for Best Play, whilst its 1984 Broadway premiere garnered multiple Tony Award nominations and just a year later, it won the Pulitzer Award for Drama. In 1992 the play was adapted by Mamet into an Academy Award nominated film featuring an all-star cast including Jack Lemmon, Al Pacino, Ed Harris, Alan Arkin, Kevin Spacey and Jonathan Pryce. -

Rebecca Brower Theatre Designer

REBECCA BROWER THEATRE DESIGNER www.rebeccabrower.com [email protected] QUALIFICATIONS BA (Hons) Theatre Practice Design for Stage The Royal Central School of Speech & Drama Distinction Diploma in Art Foundation Studies Buckinghamshire New University AWARDS Off West End: 2013 Nomination for ‘Best Set Design’ for Hamlet, The Rose Theatre, The Globe. Equity: In November 2012 Rebecca Won the Young Equity Member’s Bursary. The Stage Newspaper: In January 2011 Rebecca was awarded the Design award aimed at up and coming Designers. EMPLOYMENT 2012 - Current - Assistant/Associate to Stage Designer Jon Bausor. Rebecca assists Jon in the overall visualisation of each production designed. This includes model making, drafting, research and artwork. Up and coming companies include; Lyric Hammersmith, Regents Park Open Air Theatre and Oslo Opera House. 2012 - Design Assistant - London 2012 Olympic Ceremonies Within the Design Team Rebecca’s role was to assist the Designers with the overall visualisation for the Opening and Closing Ceremony for the Olympic and Paralympic games. Rebecca assisted the Designers; Mark Tildesley, Es Devlin and Jon Bausor. 2011: In the role of Assistant Associate Designer - The National Theatre Rebecca worked as a freelancer and was to be the general assistant for the Digital Drawings and Design Office. She worked closely with the Draftsmen, Designers and also designed in house corporate events and exhibitions. DESIGN WORK DATE ROLE PRODUCTIONS COLLABORATORS VENUE 2015 Associate Designer Bugsy Malone Director: Sean -

BBC TWO Autumn 2005

AUTUMN 2005 HIGHLIGHTS AUTUMN 2005 HIGHLIGHTS ARENA - NO DIRECTION HOME: BOB DYLAN Bob Dylan, the incomparable singer/songwriter of modern times, and Martin Scorsese, arguably the greatest film- maker of his generation, unite for these extraordinary films exploring Dylan’s formative years when he created the albums that, many agree, changed the world. Scorsese, a “great fan” of Dylan, directs this documentary featuring major, brand-new interviews with the famously private Dylan alongside contributions from key figures and previously unreleased material. These unique films are the product of a marriage between two multi-award-winning arts strands – the BBC’s Arena and PBS’ American Masters in the US – and are accompanied by a Dylan season on BBC Four. IC 1 ROME ROME IS A SPECTACULAR EPIC DRAMA SERIES FOR BBC TWO WHICH CHRONICLES THE RISE OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE THROUGH THE EYES OF TWO FOOT SOLDIERS. Co-produced with HBO, it’s the powerful saga of two ordinary Roman soldiers, Lucius Vorenus and Titus Pullo, who unwittingly become entwined in the historical events of ancient Rome.An intimate drama of love and betrayal, masters and slaves, husbands and wives, it portrays a fascinating and influential period of history: the death of a republic and the birth of an empire.The series begins in 52BC, as Gaius Julius Caesar completes his conquest of Gaul after eight years of war and prepares to return to Rome. Ciaran Hinds stars as Gaius Julius Caesar; Kevin McKidd as Lucius Vorenus; Ray Stevenson as Titus Pullo; James Purefoy as Mark Antony; Kenneth Cranham as Pompey Magnus; Lindsay Duncan as Servilia; Polly Walker as Atia; Indira Varma as Niobe;Tobias Menzies as Brutus; Kerry Condon as Octavia; and Max Pirkis as Gaius Octavian, who later becomes the first Emperor of Rome. -

A Score by Clint Mansell

A SCORE BY CLINT MANSELL ORIGINAL SOUNDTRACK RECORDING 01 CRITICAL MASS 02 SILENT CORRIDORS 03 THE WORLD BEYOND THE HIGH-RISE 04 THE VERTICAL CITY 05 THE CIRCLE OF WOMEN 06 “BUILT, NOT FOR MAN, BUT FOR MAN’S ABSENCE” 07 DANGER IN THE STREETS OF THE SKY 08 “SOMEHOW THE HIGH-RISE PLAYED INTO THE HANDS OF THE MOST PETTY IMPULSES” 09 CINE-CAMERA CINEMA 10 JEREMY THOMAS AND HANWAY FILAMS, FILROYALM4 AND BFI PRESENT IN ASSOCIA TIONFLYING WITH NORTHERN IRELAND SCHOOL SCREEN, INGENIOUS MEDIA, SCOPE PICTURES AND S FILMS A RECORDED PICTURE COMPANY11 PRODUC TION A FILM BY BEN WHEATLEY TOM HIDDLTHEESTON JEREMY EVENING’S IRONS SIENNA MILLER LUKE EVANS ENTERTAINMENT ELISABETH MOSS JAMES PUREFOY KEELEY HAWES “HIGH-RISE” DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY LAURIE ROSE PRODUCTION DESIGNER MARK TILDESLEY EDITED BY AMY JUMP AND BEN WHEATLEY MUSIC BY CLINT MANSELL 12 COSTUME DESIGNER ODILE DICKS-MIREAUX HAIR AND MAKE-UP DESIGNER WAKANA YOSHIHARA SOUND DESIGN MARTIN PAVEY CASTING BY NINA GOLD AND THEO PARK BLOOD GARDEN EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS PETER WATSON THORSTEN SCHUMACHER LIZZIE FRANCKE SAM LAVENDER ANNA HIGGS GABRIELLA MARTINELLI CHRISTOPHER SIMON GENEVIÈVE LEMAL CO-PRODUCER ALAINÉE KENT CO-PRODUCED BY NICK O’HAGAN BASED ON THE NOVEL BY J.G. BALLARD SCREENPLAY BY AMY JUMP PRODUCED BY JEREMY THOMAS DIRECTED BY BEN WHEATLEY JEREMY THOMAS AND HANWAY FILMS, FILM4 AND BFI PRESENT IN ASSOCIATION WITH NORTHERN IRELAND SCREEN, INGENIOUS MEDIA, SCOPE PICTURES AND S FILMS A RECORDED PICTURE COMPANY PRODUCTION A FILM BY BEN WHEATLEY TOM HIDDLESTON JEREMY IRONS SIENNA MILLER LUKE -

Dossier De Presse

JEREMY THOMAS présente u n f i l m d e BEN WHEATLEY D’APRÈS LE ROMAN “I.G.H” DE J.G. BALLARD avec TOM HIDDLESTON, JEREMY IRONS, SIENNA MILLER, LUKE EVANS, ELISABETH MOSS UK - DURÉE : 1H 59 – FORMAT : 2.39 - 5.1 DISTRIBUTION THE JOKERS FILMS 19, rue de Liège - 75009 Paris RELATIONS PRESSE www.thejokersfilms.com Marie Queysanne EN ASSOCIATION AVEC ASSISTÉE DE LE PACTE Charly Destombes 5, rue Darcet - 75017 Paris 113, rue Vieille du Temple - 75003 Paris Tél. : 01 44 69 59 59 tél : 01 42 77 03 63 www.le-pacte.com [email protected] / [email protected] SORTIE NATIONALE : 6 AVRIL 2016 Matériel de presse téléchargeable sur : www.highrise-lefilm.com « Avec ses quarante étages et ses mille appartements, L’HISTOIRE la tour n’offrait que trop de possibilités de violences et d’affrontements » 1975. Le Dr Robert Laing, en quête d’anonymat, emménage près de Londres dans « Les vieilles divisions sociales fondées sur la puissance, un nouvel appartement d’une tour à peine achevée; mais il va vite découvrir que le capital et l’égoïsme avaient ressurgi, ici comme ailleurs » ses voisins, obsédés par une étrange rivalité, n’ont pas l’intention de le laisser en paix… Bientôt, il se prend à leur jeu. « C’était bien à une redistribution verticale des trois classes traditionnelles Et alors qu’il se démène pour faire respecter sa position sociale; ses bonnes manières que la tour avait d’ores et déjà procédé » et sa santé mentale commencent à se détériorer en même temps que l’immeuble : les éclairages et l’ascenseur ne fonctionnent plus mais la fête continue! L’alcool est devenu la première monnaie d’échange et le sexe la panacée. -

The Story of Macbeth Playbill

The Story of Macbeth Playbill Original Story ‘Macbeth’ by:A William Shakespeare At Bucks County Playhouse 70 S Main St, New Hope, PA 18938 Plot Summary If you were told that sometime in the future, all of your wildest dreams and wishes would come true, what would you do? The story of Macbeth is a world-renowned classic by the very talented playwright, William Shakespeare. The story takes place during the Middle Ages in Scotland. ‘Macbeth’ mostly revolves around the main character, Macbeth, a war general and Lord, and his many battles. Battles with other people, battles with fate, and even battles with himself. He himself is told that many of his secret desires will come to life, eventually. When he decides what he will do because of this new information, chaos ensues. So, if you had the chance to change your fate, would you? Cast King Duncan………………….James Mcavoy Malcolm…………………Daniel Radcliffe Donalbain…………………Matthew Lewis Macbeth…………………Johnny Depp Lady Macbeth…………………Helena Bonham Carter Banquo…………………James Purefoy Fleance…………………Josh Feldman Macduff…………………Jonny Lee Miller Lennox…………………Leonardo DiCaprio Ross…………………Brad Pitt Gentlewoman…………………Emma Watson Captain…………………Sean Connery Three Murderers of Banquo……………….Tim Curry, Orlando Bloom, Mel Gibson Three Witches………………… Winona Ryder,Bette Midler, Cher Hecate…………………Maggie Smith ~Meet Our Actors And Characters~ Actor Biographies and Character Biographies James Mcavoy (King Duncan) James Mcavoy was born on April 21, 1979 in Port Glasgow, Scotland. He starred in another production of Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” while working in theatre. He has appeared in films such as Filth (2013), X-Men: Days of Future Past (2014), and is extremely well known for his appearance in Disney’s adaptation of CS Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe as Mr.