Environmental Technical Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Country Urban Park Barometer

3333333 Black Country Urban Park Barometer April 2013 DRAFT WORK IN PROGRESS Welcome to the Black Country Urban Park Barometer. Transformation of the Environmental Infrastructure is one of the key to drivers identified in the Black Country Strategy for Growth and Competitiveness. The full report looks at the six themes created under the ‘Urban Park’ theme and provides a spatial picture of that theme accompanied with the key assets and opportunities for that theme. Foreword to be provided by Roger Lawrence The Strategic Context Quality of the Black Country environment is one of the four primary objectives of the Black Country Vision that has driven the preparation of the Black Country Strategy for Growth and Competitiveness through the Black Country Study process. The environment is critical to the health and well-being of future residents, workers and visitors to the Black Country. It is also both a major contributor to, and measure of, wider goals for sustainable development and living as well as being significantly important to the economy of the region. The importance and the desire for transforming the Black Country environment has been reinforced through the evidence gathering and analysis of the Black Country Study process as both an aspiration in its own right and as a necessity to achieve economic prosperity. Evidence from the Economic and Housing Studies concluded that ‘the creation of new environments will be crucial for attracting investment from high value-added firms’ and similarly that ‘a high quality healthy environment is a priority for ‘knowledge workers’. The Economic Strategy puts ‘Environmental Transformation’ alongside Education & Skills as the fundamental driver to achieve Black Country economic renaissance and prosperity for its people. -

Vebraalto.Com

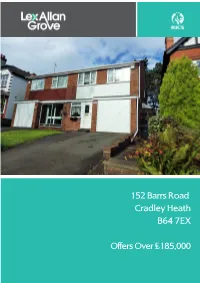

152 Barrs Road Cradley Heath B64 7EX Offers Over £185,000 “PERFECT FOR HADEN HILL PARK” Located at this popular residential address stone’s throw from Haden Hill Park, this semi detached house must be viewed to be appreciated. This fine family home offers well presented accommodation to include a welcoming reception area / dining room, generous lounge and fitted kitchen to the ground floor; fabulous master bedroom, two further bedrooms and shower room to the first floor, good sized rear garden and driveway parking to the front leading to an integral garage, all conveniently placed for good local schools, shops and public transport links (in particular Old Hill train station). Please call at the earliest opportunity to arrange your opportunity to view. PS 29/10/18 V1 EPC=E Offers Over £185,000 Freehold Location Cradley Heath lies to the North of Halesowen and falls within the boundaries of Sandwell Borough Council. As the name suggests it was originally Heathland between Cradley, Netherton and Old Hill. During the early 19th century a number of cottages were built encroaching onto the heath along the banks of the River Stour, mainly occupied by home industries such as nail making. During the industrial revolution Cradley Heath developed and became famous not only for nails but was once known as the world centre of chain making. It was the birthplace for the Black Country Bugle and is thought to be the historic home of the Staffordshire Bull Terrier. In fact you would be hard pushed to find anywhere more Black Country than Cradley Heath. -

Vebraalto.Com

57 Sherbourne Road Cradley Heath, West Midlands B64 7PX Guide Price £350,000 'STUNNING FIVE BED FAMILY HOME' This five bedroom detached property is ideally positioned towards the end of a popular cul de sac within close reach of local amenities and commuter links. The property briefly comprises of good size driveway to the front giving access to the garage, porch, entrance hallway, lounge, dining room, kitchen, utility room, downstairs w.c., to the first floor off a split landing are five bedrooms and house bathroom, finally to the rear is a beautifully maintained garden with attractive woodland views. Call the office at your earliest opportunity to arrange a viewing. LA 13/10/2020 V1 EPC=D The Spacious lounge Diner Location Cradley Heath lies to the North of Halesowen and falls within the boundaries of Sandwell Borough Council. As the name suggests it was originally Heathland between Cradley, Netherton and Old Hill. During the early 19th century a number of cottages were built encroaching onto the heath along the banks of the River Stour, mainly occupied by home industries such as nail making. During the industrial revolution Cradley Heath developed and became famous not only for nails but was once known as the world centre of chain making. It was the birthplace for the Black Country Bugle and is thought to be the historic home of the Staffordshire Bull Terrier. In fact you would be hard pushed to find anywhere more Black Country than Cradley Heath. Cradley Heath is great place for first time buyers on a limited budget. -

X10 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

X10 bus time schedule & line map X10 Birmingham - Gornal Wood via Halesowen, Merry View In Website Mode Hill The X10 bus line (Birmingham - Gornal Wood via Halesowen, Merry Hill) has 6 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Birmingham: 4:29 AM - 10:10 PM (2) Gornal Wood: 6:40 AM - 5:04 PM (3) Halesowen: 7:40 PM - 11:10 PM (4) Holly Hall: 6:19 PM - 7:30 PM (5) Merry Hill: 5:25 AM - 11:10 PM (6) Tansey Green: 4:44 PM - 6:59 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest X10 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next X10 bus arriving. -

Walking and Cycling in the Black Country

in the Black Country Introduction There’s never been a better time to get active for your health and wellbeing. You’ve been advised to start being a bit more active and there’s lot of reasons why this is a good idea. We understand that making those first changes to your lifestyle can often be the hardest ones to take. This booklet will help you make decisions on how and where to be active in the surrounding area. PLEASE NOTE: Please be safe when visiting parks and open spaces. If outdoor gym or play equipment is available for use, please use it responsibly and follow Public Health England guidance on hand washing. Please don’t visit these spaces if you’re suffering with symptoms of coronavirus. Please keep your distance if you’re walking or on a bike, staying at least 2 metres away from other people. Benefits to Activity It also reduces your chances of developing a number of preventable health conditions 50% less chance of developing Type 2 Diabetes 50% less chance of developing high blood pressure 40% less chance of developing coronary heart disease 35% less chance of developing cardiovascular disease 30% less chance of having a stroke 25% less chance of developing certain types of cancer (including breast and colon) 25% less chance of developing joint and back pain 21% less chance of having a fall Love Exploring There are lots of ways to enjoy all of the open spaces that the Black Country has to offer. Active Black Country and local partners have teamed up with Love Exploring to bring a new interactive app to some of our parks and green It’s currently available at spaces. -

Download This File

www.sandwell.gov.uk Sandwell @sandwellcouncil SUMMER 2019 Sandwell is going for gold Full story on page 7 Sign up to Sandwell Council email updates SHAPEJazz and Youth summer Pete’s amazing Music school for News from your www.sandwell.gov.uk/emailupdates Festivalfun – Pages – Page 2 and 3 5 story – Page 3 Sandwell – Page 10 town – Pages 18-23 2 The Sandwell Herald Jazz Festival comes to Sandwell (Mostly FREE indicates *charges Friday 19 July 12:00 Sandwell Arts Café Bruce Adams & Dave Newton 19:00 Lightwoods Park Bruce Adams/Dave Newton Quartet 19:00 West Bromwich Central Library *Ricky Cool & the In Crowd (£5.50 advance, £7.50 door) 19:00 Manor House, Stone Cross Les Zautos Stompers De Paris (France) Saturday 20 July 14:30 Wednesbury Museum & Art Gallery Florence Joelle (France) 19:00 Cradley Heath Library Bobby Woods (USA) 19:00 Wednesbury Library Anvil Chorus Sunday 21 July 14:00 Manor House, Stone Cross Rip Roaring Success 19:00 Thimblemill Library The Schwings (Lithuania) Monday 22 July 19:00 Great Bridge Library Roy Forbes Tuesday 23 July 19:00 Bleakhouse Library The Dirty Ragtimers (France) Wednesday 24 July 19:00 Wednesbury Library Deborah Rose & Martin Riley Thursday 25 July 19:00 Great Barr Library Bob Wilson & Honeyboy Hickling Friday 26 July 12:00 Sandwell Arts Café Val Wiseman & the Wise Guys 12:00 Glebefields Library Jules Cockshott from Ukulele Rocks (ukulele workshop for all) 19:00 Blackheath Library *Potato Head Jazz Band (Spain) (£5.50 advance, £7.50 door) Saturday 27 July 11:00 New Square Shopping Centre Potato Head Jazz Band (Spain) 12:45 New Square Shopping Centre Ricky Cool & the In Crowd 14:30 New Square Shopping Centre Tenement Jazz Band (Scotland) 19:00 West Bromwich Central Library *King Pleasure & the Biscuit Boys (£12.50 advance, £15 door) Sunday 28 July 14:00 Haden Hill House Tenement Jazz Band (Scotland) 14:30 Oak House, West Bromwich David Moore Blues Band Enjoyed the festival? There are more jazz and blues events happening in August, September and October in Sandwell Libraries. -

Proposed Black Country UNESCO Global Geopark

Great things to see and do in the Proposed Black Country UNESCO Global Geopark Black Country UNESCO Global Geopark Project The layers lying above these are grey muddy Welcome to the world-class rocks that contain seams of ironstone, fireclay heritage which is the Black and coal with lots of fossils of plants and insects. These rocks tell us of a time some 310 million Country years ago (called the Carboniferous Period, The Black Country is an amazing place with a named after the carbon in the coal) when the captivating history spanning hundreds of Black Country was covered in huge steamy millions of years. This is a geological and cultural rainforests. undiscovered treasure of the UK, located at the Sitting on top of those we find reddish sandy heart of the country. It is just 30 minutes from rocks containing ancient sand dunes and Birmingham International Airport and 10 minutes pebbly river beds. This tells us that the landscape by train from the city of Birmingham. dried out to become a scorching desolate The Black Country is where many essential desert (this happened about 250 million years aspects of the Industrial Revolution began. It ago and lasted through the Permian and Triassic was the world’s first large scale industrial time periods). landscape where anything could be made, The final chapter in the making of our landscape earning it the nick-name the ‘workshop of the is often called the’ Ice Age’. It spans the last 2.6 world’ during the Industrial Revolution. This million years of our history when vast ice sheets short guidebook introduces some of the sites scraped across the surface of the area, leaving and features that are great things to see and a landscaped sculpted by ice and carved into places to explore across many parts of The the hills and valleys we see today. -

Lantern Slides Illustrating Zoology, Botany, Geology, Astronomy

CATALOGUES ISSUED! A—Microscope Slides. B—Microscopes and Accessories. C—Collecting Apparatus D—Models, Specimens and Diagrams— Botanical, Zoological, Geological. E—Lantfrn Slides (Chiefly Natural History). F—Optical Lanterns and Accessories. S—Chemicals, Stains and Reagents. T—Physical and Chemical Apparatus (Id Preparation). U—Photographic Apparatus and Materials. FLATTERS & GARNETT Ltd. 309 OXFORD ROAD - MANCHESTER Fourth Edition November, 1924 This Catalogue cancels all previous issues LANTERN SLIDES illustrating Zoology Birds, Insects and Plants Botany in Nature Geology Plant Associations Astronomy Protective Resemblance Textile Fibres Pond Life and Sea and Shore Life Machinery Prepared by FLATTERS k GARNETT, LTD Telephone : 309 Oxford Road CITY 6533 {opposite the University) Telegrams : ” “ Slides, Manchester MANCHESTER Hours of Business: 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. Saturdays 1 o’clock Other times by appointment CATALOGUE “E” 1924. Cancelling all Previous Issues Note to Fourth Edition. In presenting this New Edition we wish to point out to our clients that our entire collection of Negatives has been re-arranged and we have removed from the Catalogue such slides as appeared to be redundant, and also those for which there is little demand. Several new Sections have been added, and, in many cases, old photographs have been replaced by better ones. STOCK SLIDES. Although we hold large stocks of plain slides it frequently happens during the busy Season that particular slides desired have to be made after receipt of the order. Good notice should, therefore, be given. TONED SLIDES.—Most stock slides may be had toned an artistic shade of brown at an extra cost of 6d. -

A Short History of the Dudley & Midland

A Short History of the Dudley & Midland Geological Societies A Cutler Summary The history and development of the Dudley Geological Societies is traced with the aid of published transactions and other manuscript material. Both Societies established geological museums in Dudley, the surviving collections of which are now in the care of the Local Authority. Introduction It is not common knowledge that a geological society existed in the Black Country during the nineteenth century and probably even less so that there were two societies at different periods, which shared similar titles. That these societies existed at all should come as no surprise. The nineteenth century was a period of great scientific advancement and popular interest in all sciences was high. The period too was one of great industrial activity particularly in the Black Country and geological problems of a very practical nature relating to mining served to make the societies ideal forums for all interested parties. They were both typical nineteenth century scientific societies and possessed many essentially amateur members. But their contribution to Black Country geology was certainly not amateur and has proved to be of lasting value. The Original Society The original or first society (even referred to as the parent society in later references) was formed in 1841 and quickly attracted a most impressive total of 150 subscribing members. Lord Ward accepted the office of President and some thirty local industrialists, geologists and Members of Parliament became Vice- Presidents. The list of patrons included no less than thirteen peers of the realm, three Lord Bishops and Sir Robert Peel who is perhaps more well known for his association with the first constabularies. -

PLATFORM 3 Is Published By: the Stourbridge Line User Group, 46 Sandringham Road, Wordsley, Stourbridge, West Midlands, DY8 5HL

Issue 2 May 2016 CONTENTS 2 Birmingham Moor Street to Hockley 4 Winson Green to Smethwick West 6 Rood End to Old Hill 8 Cradley Heath to Lye 10 Stourbridge Junction to Blakedown 12 Kidderminster to Droitwich Spa 14 Fernhill Heath to Worcester Foregate Street 16 Henwick to Great Malvern PLATFORM 3 is published by: The Stourbridge Line User Group, 46 Sandringham Road, Wordsley, Stourbridge, West Midlands, DY8 5HL - 1 - www.stourbridgelineusergroup.info A VIEW FROM THE WINDOW Our journey starts on platform 2 at BIRMINGHAM MOOR STREET, a station beautifully restored in 2005/2006 in 1909 GWR style to replace the functional and ugly 1987 tin sheds on the through platforms and reopen the derelict closed terminus. Birmingham Moor Street As soon as we clear the platform we enter the 635 yard long Snow Hill Tunnel and climb at 1 in 45. While still in the tunnel, a side tunnel joined from our left hand side. This tunnel originated in the basement of the Bank of England building at the junction of Temple Row and St Philip’s Place, and was used by bullion trains that reversed from platform 1 at Snow Hill to the bank. Immediately after leaving the gloom of the tunnel, we enter the gloom of BIRMINGHAM SNOW HILL, opened on 5 October 1987 to replace the much grander GWR station that closed on 6 March 1972. It was unfortunate that, when the new station was built, it was decided to build a three storey car park on top of it and this has served to make the station dark and uninviting. -

Download This File

Sandwell MBC 2020 Air Quality Annual Status Report (ASR) In fulfilment of Part IV of the Environment Act 1995 Local Air Quality Management January 2021 (Reporting on calendar year 2019) LAQM Annual Status Report 2020 Sandwell MBC Local Authority Elizabeth Stephens and Sophie Morris Officer Department Public Health Jack Judge House Halesowen Street Address Oldbury West Midlands B69 9EN Telephone 0121 569 6608 E-mail [email protected] Report Reference Sandwell ASR 2020 number Date January 2021 LAQM Annual Status Report 2020 Executive Summary: Air Quality in Our Area Sandwell Metropolitan Borough Council (SMBC) lies in the heart of the West Midlands, in an area of the UK known as "The Black Country". It is part of the West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA) sharing full membership with six other authorities; Birmingham, Coventry, Dudley, Solihull, Walsall and Wolverhampton. It is a densely populated area covering approximately 8,600 hectares and approximately 327,378 1 residents. This report fulfils the requirements of the Local Air Quality Management (LAQM) process as set out in Part IV of the Environment Act (1995), the Air Quality Strategy for England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland 2007 and the relevant Policy and Technical Guidance documents. The LAQM process places an obligation on all local authorities to regularly review and assess air quality in their areas, and to determine whether the national air quality objectives are likely to be achieved. Where exceedances are demonstrated or considered likely, the local authority must then declare an Air Quality Management Area (AQMA) and prepare an Air Quality Action Plan (AQAP) setting out the measures it intends to put in place in pursuit of the objectives. -

Application Dossier for the Proposed Black Country Global Geopark

Application Dossier For the Proposed Black Country Global Geopark Page 7 Application Dossier For the Proposed Black Country Global Geopark A5 Application contact person The application contact person is Graham Worton. He can be contacted at the address given below. Dudley Museum and Art Gallery Telephone ; 0044 (0) 1384 815575 St James Road Fax; 0044 (0) 1384 815576 Dudley West Midlands Email; [email protected] England DY1 1HP Web Presence http://www.dudley.gov.uk/see-and-do/museums/dudley-museum-art-gallery/ http://www.blackcountrygeopark.org.uk/ and http://geologymatters.org.uk/ B. Geological Heritage B1 General geological description of the proposed Geopark The Black Country is situated in the centre of England adjacent to the city of Birmingham in the West Midlands (Figure. 1 page 2) .The current proposed geopark headquarters is Dudley Museum and Art Gallery which has the office of the geopark coordinator and hosts spectacular geological collections of local fossils. The geological galleries were opened by Charles Lapworth (founder of the Ordovician System) in 1912 and the museum carries out annual programmes of geological activities, exhibitions and events (see accompanying supporting information disc for additional detail). The museum now hosts a Black Country Geopark Project information point where the latest information about activities in the geopark area and information to support a visit to the geopark can be found. Figure. 7 A view across Stone Street Square Dudley to the Geopark Headquarters at Dudley Museum and Art Gallery For its size, the Black Country has some of the most diverse geology anywhere in the world.