Florida Historical Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record—Senate S1183

January 25, 2007 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S1183 gave the Iraqi people a chance for free It is with that background that, in- Iraq. A resolution was passed out on a elections and a chance to write their deed, it is a great honor for me that vote of something like 12 to 9 yester- own Constitution. Those successes the family has asked me to deliver the day. It was bipartisan in the passing, which did occur were the result of eulogy. It will be a great privilege for but it was basically a partisan vote. great determination by our troops in me, next Monday, to recall the great Save for one member of the minority uniform and many brave Iraqis who life and times of this great American on the Senate Foreign Relations Com- stepped forward and risked their lives and great Floridian. I will just mention mittee, all of the minority voted to move their nation forward. a couple of things in his career. I will against the resolution. But almost to a But we all know the situation today. elaborate at greater length and will in- person, all of the members of the Sen- As of this morning, we have lost 3,057 troduce that eulogy into the RECORD of ate Foreign Relations Committee, both American soldiers. We know that over the Senate after I have given it. sides of the aisle, had expressed their 23,000 have returned from Iraq with in- I wish to mention that was a Senate dissatisfaction, individually in their juries, almost 7,000 with serious inju- which had giants with whom all of us statements in front of the committee, ries—amputations, blindness, serious in my generation grew up—Symington with the President’s intention to in- burns, traumatic brain injury. -

History of the Orange Belt Railway

HISTORY OF THE ORANGE BELT RAILWAY As the 1880's unfolded, Florida's frontier was being penetrated by a system of three-foot gauge railroads, spurred on by a generous state land grant. This story focuses on one of the last common carrier narrow gauge roads to be built in Florida, which was also one of the last to be converted to standard gauge. Petrovitch A. Demenscheff was born in Petrograd, Russia in 1850. His family was of the nobility with large estates. He was the first cousin of Prince Petroff and a captain in the Imperial Guard. He received training as a forester managing his large family estates, which would serve him well in the future. In 1880 he was exiled from Russia, and with his wife, children and servant immigrated to America, Anglicizing his name to Peter Demens. For some odd reason he headed south to Florida and obtained a job as a laborer at a sawmill in Longwood, Florida. He worked hard and within a year was appointed manager. Later with the money he saved he became partners with the owners and then quickly bought them out. Demens soon became one of the biggest contractors in the state, building houses, stations, hotels and railroads throughout Florida. One railroad contract was the narrow gauge Orange Belt Railway that he took over when they couldn't pay for the work. The Orange Belt Railway at first was a real estate promotion, using mule power (his name was Jack) and wood rails from Longwood to Myrtle Lake. When Demens took the road over he formed an operating company called the Orange Belt Investment Company. -

U.S. President's Committee for Hungarian Refugee Relief

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS U.S. PRESIDENT’S COMMITTEE FOR HUNGARIAN REFUGEE RELIEF: Records, 1957 A67-4 Compiled by Roland W. Doty, Jr. William G. Lewis Robert J. Smith 16 cubic feet 1956-1957 September 1967 INTRODUCTION The President’s Committee for Hungarian Refugee Relief was established by the President on December 12, 1956. The need for such a committee came about as a result of the United States’ desire to take care of its fair share of the Hungarians who fled their country beginning in October 1956. The Committee operated until May, 1957. During this time, it helped re-settle in the United States approximately 30,000 refugees. The Committee’s small staff was funded from the Special Projects Group appropriation. In its creation, the Committee was assigned the following duties and objectives: a. To assist in every way possible the various religious and other voluntary agencies engaged in work for Hungarian Refugees. b. To coordinate the efforts of these agencies, with special emphasis on those activities related to resettlement of the refugees. The Committee also served as a focal point to which offers of homes and jobs could be forwarded. c. To coordinate the efforts of the voluntary agencies with the work of the interested governmental departments. d. It was not the responsibility of the Committee to raise money. The records of the President’s Committee consists of incoming and outgoing correspondence, press releases, speeches, printed materials, memoranda, telegrams, programs, itineraries, statistical materials, air and sea boarding manifests, and progress reports. The subject areas of these documents deal primarily with requests from the public to assist the refugees and the Committee by volunteering homes, employment, adoption of orphans, and even marriage. -

Florida Jewish History Month January

Florida Jewish History Month January Background Information In October of 2003, Governor Jeb Bush signed a historic bill into law designating January of each year as Florida Jewish History Month. The legislation for Florida Jewish History Month was initiated at the Jewish Museum of Florida by, the Museum's Founding Executive Director and Chief Curator, Marcia Zerivitz. Ms. Zerivitz and State Senator Gwen Margolis worked closely with legislators to translate the Museum's mission into a statewide observance. It seemed appropriate to honor Jewish contributions to the State, as sixteen percent, over 850,000 people of the American Jewish community lives in Florida. Since 1763, when the first Jews settled in Pensacola immediately after the Treaty of Paris ceded Florida to Great Britain from Spain, Jews had come to Florida to escape persecution, for economic opportunity, to join family members already here, for the climate and lifestyle, for their health and to retire. It is a common belief that Florida Jewish history began after World War II, but in actuality, the history of Floridian Jews begins much earlier. The largest number of Jews settled in Florida after World War II, but the Jewish community in Florida reaches much further into the history of this State than simply the last half-century. Jews have actively participated in shaping the destiny of Florida since its inception, but until research of the 1980s, most of the facts were little known. One such fact is that David Levy Yulee, a Jewish pioneer, brought Florida into statehood in 1845, served as its first U.S. -

Nixon's Caribbean Milieu, 1950–1968

Dark Quadrant: Organized Crime, Big Business, and the Corruption of American Democracy Online Appendix: Nixon’s Caribbean Milieu, 1950–1968 By Jonathan Marshall “Though his working life has been passed chiefly on the far shores of the continent, close by the Pacific and the Atlantic, some emotion always brings Richard Nixon back to the Caribbean waters off Key Biscayne and Florida.”—T. H. White, The Making of the President, 19681 Richard Nixon, like millions of other Americans, enjoyed Florida and the nearby islands of Cuba and the Bahamas as refuges where he could leave behind his many cares and inhibitions. But he also returned again and again to the region as an important ongoing source of political and financial support. In the process, the lax ethics of its shadier operators left its mark on his career. This Sunbelt frontier had long attracted more than its share of sleazy businessmen, promoters, and politicians who shared a get-rich-quick spirit. In Florida, hustlers made quick fortunes selling worthless land to gullible northerners and fleecing vacationers at illegal but wide-open gambling joints. Sheriffs and governors protected bookmakers and casino operators in return for campaign contributions and bribes. In nearby island nations, as described in chapter 4, dictators forged alliances with US mobsters to create havens for offshore gambling and to wield political influence in Washington. Nixon’s Caribbean milieu had roots in the mobster-infested Florida of the 1940s. He was introduced to that circle through banker and real estate investor Bebe Rebozo, lawyer Richard Danner, and Rep. George Smathers. Later this chapter will explore some of the diverse connections of this group by following the activities of Danner during the 1968 presidential campaign, as they touched on Nixon’s financial and political ties to Howard Hughes, the South Florida crime organization of Santo Trafficante, and mobbed-up hotels and casinos in Las Vegas and Miami. -

Men, Women and Children in the Stockade: How the People, the Press, and the Elected Officials of Florida Built a Prison System Anne Haw Holt

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Men, Women and Children in the Stockade: How the People, the Press, and the Elected Officials of Florida Built a Prison System Anne Haw Holt Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES Men, Women and Children in the Stockade: How the People, the Press, and the Elected Officials of Florida Built a Prison System by Anne Haw Holt A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2005 Copyright © 2005 Anne Haw Holt All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Anne Haw Holt defended September 20, 2005. ________________________________ Neil Betten Professor Directing Dissertation ________________________________ David Gussak Outside Committee Member _________________________________ Maxine Jones Committee Member _________________________________ Jonathon Grant Committee Member The office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members ii To my children, Steve, Dale, Eric and Jamie, and my husband and sweetheart, Robert J. Webb iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe a million thanks to librarians—mostly the men and women who work so patiently, cheerfully and endlessly for the students in the Strozier Library at Florida State University. Other librarians offered me unstinting help and support in the State Library of Florida, the Florida Archives, the P. K. Yonge Library at the University of Florida and several other area libraries. I also thank Dr. -

Florida Historical Quarterly (ISSN 0015-4113) Is Published by the Florida Historical Society, University of South Florida, 4202 E

COVER Black Bahamian community of Coconut Grove, late nineteenth century. This is the entire black community in front of Ralph Munroe’s boathouse. Photograph courtesy Ralph Middleton Munroe Collection, Historical Association of Southern Florida, Miami, Florida. The Historical Volume LXX, Number 4 April 1992 The Florida Historical Quarterly (ISSN 0015-4113) is published by the Florida Historical Society, University of South Florida, 4202 E. Fowler Avenue, Tampa, FL 33620, and is printed by E. O. Painter Printing Co., DeLeon Springs, FL. Second-class postage paid at Tampa, FL, and at additional mailing office. POST- MASTER: Send address changes to the Florida Historical Society, P. O. Box 290197, Tampa, FL 33687. Copyright 1992 by the Florida Historical Society, Tampa, Florida. THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY Samuel Proctor, Editor Mark I. Greenberg, Editorial Assistant EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD David R. Colburn University of Florida Herbert J. Doherty University of Florida Michael V. Gannon University of Florida John K. Mahon University of Florida (Emeritus) Joe M. Richardson Florida State University Jerrell H. Shofner University of Central Florida Charlton W. Tebeau University of Miami (Emeritus) Correspondence concerning contributions, books for review, and all editorial matters should be addressed to the Editor, Florida Historical Quarterly, Box 14045, University Station, Gainesville, Florida 32604-2045. The Quarterly is interested in articles and documents pertaining to the history of Florida. Sources, style, footnote form, original- ity of material and interpretation, clarity of thought, and in- terest of readers are considered. All copy, including footnotes, should be double-spaced. Footnotes are to be numbered con- secutively in the text and assembled at the end of the article. -

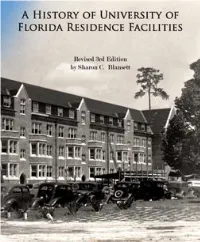

Historyof-Uffacilities.Pdf

The third time’s the charm… © 2010 University of Florida Department of Housing and Residence Education. All rights reserved. Brief quotation may be used. Other reproduction of the book, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other means requires written permission. Cover design by Nathan Weis. Editorial assistance by Darlene Niswander. Preface Contents A History of University of Florida Residence Facilities (Revised 3rd Edition) is part of an ongoing project to Buckman Hall ..........................................................................................................9 establish a central location to archive all the various types of historical information that staff donate as they Thomas Hall ..........................................................................................................12 FOHDQWKHLURIÀFHVUHWLUHRUWHUPLQDWHHPSOR\PHQWZLWKWKH8QLYHUVLW\RI)ORULGD7KHÀUVWHGLWLRQRIWKLV ERRNLQFOXGHGLQIRUPDWLRQWKURXJK7KHVHFRQGHGLWLRQLQFOXGHGXSGDWHVUHYLVLRQVDQGQHZLQIRUPDWLRQ Sledd Hall ...............................................................................................................15 JDWKHUHGVLQFH7KHWKLUGHGLWLRQLQFOXGHVXSGDWHVUHYLVLRQVDQGQHZLQIRUPDWLRQJDWKHUHGVLQFHDV well as more photographs. Fletcher Hall ..........................................................................................................17 Murphree Hall ........................................................................................................19 Historical questions pertaining to residence facilities from -

Hamilton Disston

HAMILTON DISSTON Hamilton Disston was born August 23, 1844, in Philadelphia. He worked in his father's saw manufacturing plant until he signed up to join the troops fighting in the Civil War. Twice during the early years of fighting, he enlisted, only to be hauled home after his father paid the bounty for another soldier to take his son's place. He eventually accepted his son's wishes and supplied Hamilton and 100 other workers from the saw plant with equipment to form the Disston Volunteers. Hamilton served as a private in the Union Army until the end of the war. Hamilton Disston purchased four million acres of marshland shortly after the Civil War. Included in his purchase was the small trading post of Allendale, which was eventually renamed Kissimmee. Disston wished to drain the area surrounding Kissimmee and deepen the Kissimmee River, so products could be shipped into the Gulf of Mexico and beyond. Many steamboats passed through the area with cargoes of cypress lumber and sugar cane. Disston committed suicide on April 30, 1896, after a disastrous freeze led many families to relocate further south. Disston's land company stopped payment on bonds and returned to Philadelphia. Hamilton Disston Biography by Mary Ellen Wilson and is located in the American National Biography, published by Oxford University Press, 1999. Photo from Ken Milano's archives. Hamilton Disston (23 Aug. 1844-30 Apr. 1896), land developer, was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the son of Henry Disston, an industrialist, and Mary Steelman. At the age of fifteen Disston started as an apprentice in one of the divisions of his father's factory, Keystone Saw, Tool, Steel and File Works, setting a precedent for other family members. -

Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume 63, Number 4

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 63 Number 4 Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume Article 1 63, Number 4 1984 Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume 63, Number 4 Florida Historical Society [email protected] Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Society, Florida Historical (1984) "Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume 63, Number 4," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 63 : No. 4 , Article 1. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol63/iss4/1 Society: Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume 63, Number 4 Published by STARS, 1984 1 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 63 [1984], No. 4, Art. 1 COVER Opening joint session of the Florida legislature in 1953. It is traditional for flowers to be sent to legislators on this occasion, and for wives to be seated on the floor. Florida’s cabinet is seated just below the speaker’s dais. Secretary of State Robert A. Gray is presiding for ailing Governor Dan T. McCarty. Photograph courtesy of the Florida State Archives. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol63/iss4/1 2 Society: Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume 63, Number 4 Volume LXIII, Number 4 April 1985 THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY COPYRIGHT 1985 by the Florida Historical Society, Tampa, Florida. Second class postage paid at Tampa and DeLeon Springs, Florida. Printed by E. O. Painter Printing Co., DeLeon Springs, Florida. -

February 1, 2020

Russian Heritage February 1, 2020 Russian Heritage Newsletter SAINT PETERSBURG, TAMPA, CLEARWATER, FLORIDA R u s s i a n H e r i t a g e Russian Heritage Russian Heritage NEW L o g o Winter Ball Webpage Is Being Updated We have a new logo for our It took a lot of effort, nerves, The time has come to finally get organization. Thank you stress and patience, to put this a new look and add many more Michael our webmaster who Ball together. We want to features to our webpage. It’s a helped design it. Thank All those Board tedious process but we want to Members who managed to Thank Michael the web designer make this a great event! But and maintainer for making it also thank all RH Members happen along with Zina Downen and guests who attended too. one of our Board members. RUSSIAN HERITAGE WINTER BALL A Fun Time Enjoyed by All! We had our 24th Annual Winter Ball on Saturday, January 11th, 2020 @ the St. Petersburg Yacht Club. Over 250 people attended, with several local politicians and state congressmen. It was possibly the “Best Ball Yet!” quoted by many. Rrussianheritage.org 1 Russian Heritage February 1, 2020 St Petersburg Sister Cities (Florida & Russia) This year Russian Heritage plans to get this project off the shelves and into action. After many years of silence, work has been progressing a step at a time, contacting officials from both sides. One of our main goals is to organize the student exchange program, we plan to have several activities with art and perhaps theatre events. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy.