Franchise Relocation in Major League Baseball Jeffrey M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post Game Notes Oakland Athletics Baseball Company W 7000 Coliseum Way W Oakland, CA 94621 510-638-4900 W @Athletics W @Asmediaalerts W Athletics.Com

OAKLAND ATHLETICS Post Game Notes Oakland Athletics Baseball Company w 7000 Coliseum Way w Oakland, CA 94621 510-638-4900 w @Athletics w @AsMediaAlerts w athletics.com Seattle Mariners (3-1) at Oakland Athletics (2-2) Thursday, April 3, 2014 w O.co Coliseum 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 R H E LOB Seattle 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 6 0 7 Oakland 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 3 6 2 10 W — Drew Pomeranz (1-0) L — Hector Noesi (0-1) S — None OAKLAND NOTES • The Oakland Athletics had their first walk-off win of the season tonight with a Coco Crisp home run...they had 8 walk-off wins in 2013...tonight was also their first extra-inning game of 2014 after going 7-6 in extras last season • Jesse Chavez made his first start as a member of the Oakland Athletics...matched his career high in innings pitched and finished with four strikeouts. • Ryan Cook (1 ip, 0 h, 0 r, 00 bb, 0 so) made a rehab outing with single-A Stockton tonight...Cook started the season on the DL. • Josh Donaldson (0 for 4, bb, 2 so) is now hitless in his last 14 at-bats, after starting the season 2 for 4. • Sam Fuld (1 for 5, rbi, so) hit a triple for the second consecutive night, the first time he has accomplished such a feat. • Nick Punto (2 for 5, r, so) collected his first hit as an Oakland Athletic. -

Oakland Athletics Virtual Press

OAKLAND ATHLETICS Media Release Oakland Athletics Baseball Company h 7000 Coliseum Way h Oakland, CA 94621 510-638-4900 h Public Relations Facsimile 510-562-1633 h www.oaklandathletics.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: June 16, 2010 Oakland A’s Celebrate the 1970s With Turn-Back-the-Clock Night “’70s Night” Ticket Discounts Available Through A’s Website; Joe Rudi to Throw Out First Pitch OAKLAND, Calif. – The Oakland A’s will celebrate the 1970s with a Turn-Back-the-Clock Night Saturday, June 26 at the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum in conjunction with the team’s 7:05 pm game against the Pittsburgh Pirates. As part of the promotion, the A’s are offering specially-discounted tickets of $9.70 for Plaza Level seats (regularly priced at $24) and $19.70 Lower Box seats (regularly $30), while malts and cracker jacks will be sold at Turn-Back- the-Clock prices (half off regular price). The “Swingin’ A’s” are considered one of the most dominant teams of the 1970s, winning five division titles and three consecutive pennants (1972-74) and World Series titles during the decade. Owned by Charles O Finley, the team was led by players such as Reggie Jackson, Vida Blue, Jim “Catfish” Hunter, Rollie Fingers and Joe Rudi. The 1972 Oakland A's captured the Bay Area's first ever world championship, defeating the heavily favored Cincinnati Reds in a seven-game World Series. The 1973 A’s featured three 20-game winners (Hunter, Blue, Holtzman) and defeated the New York Mets in a memorable, seven-game World Series and the following year, the A’s defeated the Los Angeles Dodgers in five games. -

Remember the Cleveland Rams?

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 7, No. 4 (1985) Remember the Cleveland Rams? By Hal Lebovitz (from the Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 20, 1980) PROLOGUE – Dan Coughlin, our bubbling ex-baseball writer, was saying the other day, “The Rams are in the Super Bowl and I’ll bet Cleveland fans don’t even know the team started right here.” He said he knows about the origin of the Rams only because he saw it mentioned in a book. Dan is 41. He says he remembers nothing about the Rams’ days in Cleveland. “Probably nobody from my generation knows. I’d like to read about the team, how it came to be, how it did, why it was transferred to Los Angeles. I’ll bet everybody in town would. You ought to write it.” Dan talked me into it. What follows is the story of the Cleveland Rams. If it bores you, blame Coughlin. * * * * Homer Marshman, a long-time Cleveland attorney, is the real father of the Rams. He is now 81, semi- retired, winters in his home on gold-lined Worth Avenue in Palm Beach, Fla., runs the annual American Cenrec Society Drive there. His name is still linked to a recognized law firm here – Marshman, Snyder and Corrigan – and he owns the Painesville harness meet that runs at Northfield each year. The team was born in 1936 in exclusive Waite Hill, a suburb east of Cleveland. Marshman vividly recalls his plunge into pro football. “A friend of mine, Paul Thurlow, who owned the Boston Shamrocks, called me. He said a new football league was being formed. -

2019 Cleveland Heights Tigers Football Roster

THREE OHSAA FOOTBALL PLAYOFF APPEARANCES (2011, 2013, and 2015) CLEVELAND HEIGHTS 2019 TIGERS FOOTBALL GAME NOTES 2019 Schedule & Results Gameday Storylines Game #9 • Friday, October 25, 2019 • Cleveland Heights Stadium • 7:00 PM kickoff MEDINA BEES L 10-21 Friday, August 30 Ken Dukes Stadium Shaw 2-6 overall 0-3 LEL GLENVILLE TARBLOODERS W 17-0 CARDINALS Friday, September 6 Cleveland Heights High School Stadium Cleveland Heights 7-1 overall SHAKER HTS RED RAIDERS W 50-6 Saturday, September 14 TIGERS 3-0 LEL Russell H. Rupp Field Last Meeting between Cleveland Heights and Shaw: LAKE CATHOLIC COUGARS W 28-23 October 19, 2018 (week 9); Cleveland Heights 17, Shaw 8 Friday, September 20 Jerome T. Osborne Stadium Cleveland Heights Tigers in Week 9 games since 2000 Week 9 has been one of the most successful week's of the season for the Tigers over the past two decades. Since WALSH JESUIT WARRIORS W 38-30 2000, the Tigers are 12-7 overall in Week 9 games, having won 4 in a row, 5 of their last 6 and 8 of their last 10 Friday, September 27 games played in Week 10. The Tigers current four-game winning stream in Week 9, includes three consecutive Cleveland Heights High School Stadium wins over the Shaw Cardinals LORAIN TITANS W 35-28 Friday, October 4 George Daniel Field Opening Drive BEDFORD BEARCATS W 39-6 Cleveland Heights puts a 7-game winning streak on the line when the Tigers host Friday, October 11 Cleveland Heights High School Stadium the Shaw Cardinals for an LEL matchup in Week 9. -

Home Team: the Turbulent History of the San Francisco Giants Online

9mges (Ebook free) Home Team: The Turbulent History of the San Francisco Giants Online [9mges.ebook] Home Team: The Turbulent History of the San Francisco Giants Pdf Free Robert F. Garratt DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #146993 in Books NEBRASKA 2017-04-01Original language:English 8.88 x 1.07 x 6.25l, .0 #File Name: 080328683X264 pagesNEBRASKA | File size: 27.Mb Robert F. Garratt : Home Team: The Turbulent History of the San Francisco Giants before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Home Team: The Turbulent History of the San Francisco Giants: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. A GRAND SLAMBy alain robertIf you are looking for a coffee table book filled with color pictures,this book is not for you.However,if you want to know about the team's turbulent sixty year history and those legendary CANDLESTICK stories that became a trademark of the city, this book will please you.There are also anecdotes about the team's early stars like MAYS,MARICHAL,CEPEDA and WILLIE THE STRETCHER McCOVEY.Well done from beginning to end.Any true baseball fan should enjoy.In case you don't remember,THE BEATLES's last concert was at CANDLESTICK in 1966.3 of 3 people found the following review helpful. Giant Fans Will Love This BookBy Dominic CarboniThe author did an outstanding job describing the Giant's move from New York to their present home. His story brought back fond memories of us teenagers sneaking into Seals stadium to watch the new home team. -

JOE LAWSON Class of 1969

JOE LAWSON Class of 1969 Joe Lawson was proudly born and raised in Seneca Falls, the oldest of 6 children born to Joseph Sr. and Helen Ferguson Lawson. As a child he grew up playing outside activities with the other neighborhood children. Most of these neighborhood gatherings revolved around sports. As they got older, they eventually branched out to other neighborhoods to create competition. Sometimes they competed with others through school, in Joe’s case, St. Patrick's. Neighborhood sports taught him competition. Since he was taller than his age group, Joe played with older kids encountering many bumps in the road. Soon thereafter came little league, school basketball, and later organized football. Throughout this period, Joe always continued to get together with his friends for no holds barred competition in all sports. That competitive application continued to grow and as an 8th grader Joe’s St. Patrick's basketball team had an undefeated season and won the league. Looking forward, some on that team have gone on to distinction in this hall of fame including Mark Piscitelli and Mike Nozzolio. Tony Ferrara was also a member of that team. Throughout, Joe’s favorite sport was football, which he continues to enjoy. An injury while playing JV as a sophomore caused his father to shut this sport down. Those were the days when kids actually listened to their parents! In high school, Joe amassed 6 varsity letters in basketball and baseball, being a starting pitcher in baseball as a freshman. An injury caused him to miss part of the sophomore basketball season, and the entire baseball season. -

Dodgers and Giants Move to the West: Causes and Effects an Honors Thesis (HONRS 499) by Nick Tabacca Dr. Tony Edmonds Ball State

Dodgers and Giants Move to the West: Causes and Effects An Honors Thesis (HONRS 499) By Nick Tabacca Dr. Tony Edmonds Ball State University Muncie, Indiana May 2004 May 8, 2004 Abstract The history of baseball in the United States during the twentieth century in many ways mirrors the history of our nation in general. When the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants left New York for California in 1957, it had very interesting repercussions for New York. The vacancy left by these two storied baseball franchises only spurred on the reason why they left. Urban decay and an exodus of middle class baseball fans from the city, along with the increasing popularity of television, were the underlying causes of the Giants' and Dodgers' departure. In the end, especially in the case of Brooklyn, which was very attached to its team, these processes of urban decay and exodus were only sped up when professional baseball was no longer a uniting force in a very diverse area. New York's urban demographic could no longer support three baseball teams, and California was an excellent option for the Dodger and Giant owners. It offered large cities that were hungry for major league baseball, so hungry that they would meet the requirements that Giants' and Dodgers' owners Horace Stoneham and Walter O'Malley had asked for in New York. These included condemnation of land for new stadium sites and some city government subsidization for the Giants in actually building the stadium. Overall, this research shows the very real impact that sports has on its city and the impact a city has on its sports. -

Table of Contents Fall & Spring 1996

Table of Contents Fall & Spring 1996 Special Collections Division the University of Texas at Arlington Libraries Vol. XI * No. 1& 2 * Fall & Spring '97 Table of Contents Fall and Spring 1996 Fall 1996 A Quarter-Century of Change, Controversy, and Chaos By Jerry L. Stafford In June of 1996, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram donated an addition to its Photograph Collection that included nearly 300,000 negatives dating from 1955 through 1979. The images document a quarter-century of significant changes. Stafford selects a number of events to spotlight in this photo-essay ranging from Rosa Parks and Elvis Pressley to Tom Landry and Nolan Ryan. Pitcher, Nolan Ryan. Friends Start Fall '96 with a Bang! By Gerald D. Saxon On September 1, the Friends of the UTA Libraries began their ninth years as an organization actively supporting the development and improvement of the Univesity Libraries. The article reviews the events and speakers who highlighted the year. Invitation cover for Friends September meeting showing a nineteenth century railroad bridge. John W. Carpenter, A Texas Giant By Shirley R. Rodnitzky The article focuses on the career of a man, who for more than three decades, was prominently identified with virtually every civic, charitable, and community enterprise in Dallas. The biographical narrative was made possiblewith the donation of the Carpenter Papers by his son, Ben H. Carptenter. The papers include 218 linear feet of files revealing fifty-plus years of twentieth century http://libraries.uta.edu/SpecColl/crose96/contents.htm[11/18/2010 10:59:21 AM] Table of Contents Fall & Spring 1996 Texas history. -

April Acquiring a Piece of Pottery at the Kidsview Seminars

Vol. 36 No. 2 NEWSLETTER A p r i l 2 0 1 1 Red Wing Meetsz Baseball Pages 6-7 z MidWinter Jaw-Droppers Page 5 RWCS CONTACTS RWCS BUSINESS OFFICE In PO Box 50 • 2000 Old West Main St. • Suite 300 Pottery Place Mall • Red Wing, MN 55066-0050 651-388-4004 or 800-977-7927 • Fax: 651-388-4042 This EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: STACY WEGNER [email protected] ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT: VACANT Issue............. [email protected] Web site: WWW.RedwINGCOLLECTORS.ORG BOARD OF DIRECTORS Page 3 NEWS BRIEFS, ABOUT THE COVER PRESIDENT: DAN DEPASQUALE age LUB EWS IG OUndaTION USEUM EWS 2717 Driftwood Dr. • Niagara Falls, NY 14304-4584 P 4 C N , B RWCS F M N 716-216-4194 • [email protected] Page 5 MIDWINTER Jaw-DROPPERS VICE PRESIDENT: ANN TUCKER Page 6 WIN TWINS: RED WING’S MINNESOTA TWINS POTTERY 1121 Somonauk • Sycamore, IL 60178 Page 8 MIDWINTER PHOTOS 815-751-5056 • [email protected] Page 10 CHAPTER NEWS, KIDSVIEW UPdaTES SECRETARY: JOHN SAGAT 7241 Emerson Ave. So. • Richfield, MN 55423-3067 Page 11 RWCS FINANCIAL REVIEW 612-861-0066 • [email protected] Page 12 AN UPdaTE ON FAKE ADVERTISING STOnewaRE TREASURER: MARK COLLINS Page 13 BewaRE OF REPRO ALBANY SLIP SCRATCHED MINI JUGS 4724 N 112th Circle • Omaha, NE 68164-2119 Page 14 CLASSIFIEDS 605-351-1700 • [email protected] Page 16 MONMOUTH EVENT, EXPERIMENTAL CHROMOLINE HISTORIAN: STEVE BROWN 2102 Hunter Ridge Ct. • Manitowoc, WI 54220 920-684-4600 • [email protected] MEMBERSHIP REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE: RUSSA ROBINSON 1970 Bowman Rd. • Stockton, CA 95206 A primary membership in the Red Wing Collectors Society is 209-463-5179 • [email protected] $25 annually and an associate membership is $10. -

Ex-Students Ex to Get Draft WASHINGTON

College Is Cleared by Judge Sunny and Cool sunny, cool today. Clear, cool WEBMLY tonight. Cloudy, cool tomor- Red Bank, Freehold row and Friday. 1 Long Branch 7 EDITION Moninoulli County's Outstanding Home Newspaper VOJ*.«>4 NO. 61 KFD BANK, N. J. WEDNESDAY, SEFTEMBFR 22,1971 Ex-Students Ex To Get Draft WASHINGTON. (AP) - present witnesses before hlfj, man with lottery no. 125 or 130,000 inductions in the cur- the president authority to Men with low draft numbers board, requiring a local or ap- lower would be* called. Wheth- rent fiscal year that began phase out undergraduate'stu- who have lost their defer- peal board to have a quorum er it will reach 140, the cur- July 1 and 140,000 in the next dent deferments. Students ments—primarily students when hearing a registrant, rent limit for ordering pre- fiscal year, both well above who entered college or trade graduated from college in and lowering the maximum induction exams, depends on this year's expected callup. school this summer or fall June or dropouts — are ex- length of service on boards the Pentagon manpower re- won't be eligible for defer- pected to be the first called from 25 to 20 years. quirements. The biggest change in the ments, nor will future under- when the Selective Service re- Pentagon officials lave said The draft bill sets a limit of draft provided in the bill gives graduates, officials said. sumes inductions. that about 20,000 draftees Draft officials gave no in- would be needed during the dication when the first men remainder of the year, in- would be called, but said men cluding a 16,009 July-August would be in uniform within request left hanging when the two weeks after President draft authority expired Juno NiXon signs the draft measure 30. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

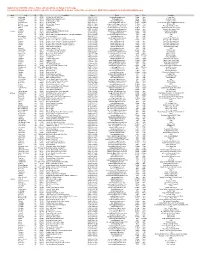

PHR Local Website Update 4-25-08

Updated as of 4/25/08 - Dates, Times and Locations are Subject to Change For more information or to confirm a specific local competition, please contact the Local Host or MLB PHR Headquarters at [email protected] State City ST Zip Local Host Phone Email Date Time Location Alaska Anchorage AK 99508 Mt View Boys & Girls Club (907) 297-5416 [email protected] 22-Apr 4pm Lions Park Anchorage AK 99516 Alaska Quakes Baseball Club (907) 344-2832 [email protected] 3-May Noon Kosinski Fields Cordova AK 99574 Cordova Little League (907) 424-3147 [email protected] 26-Apr 10am Volunteer Park Delta Junction AK 99737 Delta Baseball (907) 895-9878 [email protected] 6-May 4:30pm Delta Junction City Park HS Baseball Field Eielson AK 99702 Eielson Youth Program (907) 377-1069 [email protected] 17-May 11am Eielson AFB Elmendorf AFB AK 99506 3 SVS/SVYY (907) 868-4781 [email protected] 26-Apr 10am Elmendorf Air Force Base Nikiski AK 99635 NPRSA 907-776-8800x29 [email protected] 10-May 10am Nikiski North Star Elementary Seward AK 99664 Seward Parks & Rec (907) 224-4054 [email protected] 10-May 1pm Seward Little League Field Alabama Anniston AL 36201 Wellborn Baseball Softball for Youth (256) 283-0585 [email protected] 5-Apr 10am Wellborn Sportsplex Atmore AL 36052 Atmore Area YMCA (251) 368-9622 [email protected] 12-Apr 11am Atmore Area YMCA Atmore AL 36502 Atmore Babe Ruth Baseball/Atmore Cal Ripken Baseball (251) 368-4644 [email protected] TBD TBD TBD Birmingham AL 35211 AG Gaston