Impacts of Punahou School's Holokū Pageant: an Exploration Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mānoa Heritage Center

Mānoa Heritage Center Teacher’s Information and Resources Kūka‘ō‘ō Heiau Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………….……..3 Background Information for Teachers…………………………….….4-10 Mana, Kapu and Heiau…………………………………………….…11-12 Oli……………………………………………………………………….…13 Secondary Sources………………………………………………………..14 Mānoa Valley Timeline (Secondary Source)…………………………….14-18 Timeline Activities…………………………………………………….18-20 Primary Sources………………………………………………………20-21 Oral traditions: Kapunahou I (Primary Sources)……………….……...22-23 Suggested Questions for Kapunahou I………………………………….24 Oral traditions: Kapunahou II (Primary sources) ……………………..25-26 Suggested questions for Kapunahou II…………………………………27 Oral History: A Walk Through Old Mānoa (Primary Source)………..28-31 1820 Map and Activities (Primary Source)…………………………………31 DOE Standards……………………………………………………….32-35 About the Mānoa Heritage Center……………………………………...36 Planning Your Visit………………………………………………………37 2 Kōnāhuanui Introduction In the heart of Mānoa valley, the Mānoa Heritage Center invites you to step back in time and explore our living connections to Hawai‘i‘s past. Kūka‘ō‘ō stands as the last intact walled heiau in the greater ahupua‘a of Waikīkī. Believed to have been built by Menehune, the heiau is interpreted today as an agricultural temple. Surrounding the heiau are native Hawaiian gardens that feature an extraordinary collection of rare and endangered species, as well as plants introduced by Polynesian settlers. Our site also tells the story of Mānoa valley, once a rich agricultural area that Hawaiians farmed for centuries. Foreign contact brought many changes to the valley including immigrant resident farmers from various ethnic groups. Today Mānoa is known as one of the most desirable residential areas in Hawai‘i, but its strong sense of place endures. 3 Background Information for Teachers Mānoa Valley As part of the Ko‘olau range, the large amphitheater valley of Mānoa was carved out through wind, rain and erosion. -

Alzheimer's Caregiving Tips

MAGAZINE | VOL 10/4 • AUG/SEPT 2020 AUG/SEPT • 10/4 VOL Work Longer Alzheimer’s Reflections on When is it — Brain Caregiving a Caregiving Time to Move Smarter Tips Journey Mom or Dad? page 15 page 32 page 44 page 49 Major Complete Distribution Distribution Locations on Partners: Page 3 Get Your Magazine at These Locations 3 OAHU DISTRIBUTION LOCATIONS Maluhia Hospital COMMUNITY PARKS 15 Craigside Marukai Aina Haina, Ala Puumalu, Ala Wai, Altres Medical McKinley Carwash Asing, Crestview, Ewa Beach, Kahala, Kaimuki, Kaneohe, Kuapa Isles, Ameriprise Financial Moiliili Community Center DISTRIBUTION LOCATIONS Makakilo, Mililani, Moanalua, Pearl City, Arcadia Na Kupuna Makamae Center Pililaau, Whitmore Attention Plus Care Ohana Hearing Care Avalon Care Centers Olaloa Retirement Community OUTDOOR RACKS (OAHU) Big City Diners One Kalakaua Senior Living Alakea Street (by CPB Building) Catholic Charities Pali Momi Medical Center Bishop Street (by Bank of Hawaii) C&C of Honolulu’s Elderly Affairs Div. Palolo Chinese Home Kaheka Street (by PanAm Building) Copeland Insurance Pharmacare: Aiea Medical Bldg., King Street (by Down to Earth) & Financial Benefits Insurance Joseph Paiko Bldg. (Liliha), King Street (by Tamarind Park) Dauterman Medical & Mobility Pali Momi Medical Center (Aiea), Merchant Street (by Post Office) Don Quijote Waipahu Tamura Super Market (Waianae), Merchant Street (by Pioneer Plaza Building) Straub Pharmacy (Honolulu) Financial Benefits Isurance Is your Medicare coverage still right for you? Plaza: Mililani, Moanalua, Pearl City, -

2021 Acech Engineering Excellence Awards

Wiliki_May2021_Wiliki Sept06 4/23/21 7:20 AM Page 1 VOL. 57 NO. 3 SERVING 2000 ENGINEERS MAY 2021 2021 ACECH ENGINEERING EXCELLENCE AWARDS The 2021 American Council of Engineering Companies of Hawai'i (ACECH) Engineering Excellence Awards (EEA) was held virtually this year. The awards program culminated in a virtual event held on April 15, 2021. This year a total of 6 entries were received, all worthy and fine examples of engineering at its best. The purpose of the EEA is to showcase and honor the most outstanding work in the engineering community, projects that exemplify the highest degree of merit and ingenuity. For over 40 years, ACECH has sent top winners of the local competition to the ACEC National Competition, which is considered to be one of the most prestigious design competitions in the world. The project receiving the top honors this year, the highly coveted Grand Conceptor Award, was Punahou School’s Path to Net Zero submitted by RHA Energy Partners LLC and Ronald N.S. Ho & Associates Inc. The Lahaina Wastewater Reclamation Facility Stage 1A Improvments project submitted by Jacobs Engineering Group as well as Belt Collins’ Keauhou Beach Hotel and Site Demolition project were each awarded Grand Conceptor Award: Exterior of Old School Hall Excellence Awards. Grand Conceptor Award Winner: Punahou throughout the United States as how it can allows operators to remove tanks from service School’s Path to Net Zero. significantly impact and improve sustainable to conduct maintenance without impacting Entering Firm: RHA Energy Partners LLC and and energy initiatives. wastewater treatment. These and other Ronald N.S. -

Spring 2020 Alumni Class Notes

Alumni Notes NotesAlumni Alumni Notes Policy EDITOR’S NOTE » Send alumni updates and photographs directly to Class Correspondents. Our deadline for Class correspondents to complete the Class » Digital photographs should be high- resolution jpg images (300 dpi). notes occurred well before the COVID-19 outbreak. Thus, » Each class column is limited to 650 words so the following submissions do not make mention of the health that we can accommodate eight decades of classes in the Bulletin! crisis and its impact on communities across the globe. We » Bulletin staff reserve the right to edit, format nevertheless are including the Class notes as they were and select all materials for publication. finalized earlier this year, since we know Punahou alumni want to remain connected to each other. Mahalo for reading! Class of 1935 th REUNION 85 OCT. 8 – 12, 2020 George Ferdinand Schnack peacefully passed away on Feb. 21, 2020, at home in Honolulu, School for one year and served abroad in with all his wits and family at his side. At Class of 1941 World War II. When he returned, he studied Punahou, he was very active in sports, student medicine at Johns Hopkins University and Gregg Butler ’68 government and ROTC, and was also an editor psychiatry at the Psychiatric Institute in New (son of Laurabelle Maze ’41 Butler) and manager of the Oahuan. He took a large [email protected] | 805.501.2890 York City, where he met his wife, Patricia. role in the 1932 origination and continuing After returning to Honolulu in 1959, he opened tradition of the Punahou Carnival – which a private psychiatric practice and headed up began as a fundraiser for the yearbook. -

A Season of Growth, Change, and Excitement at Iolani Palace

KE KIAI O KA IOLANI HALE THE GUARDIAN OF IOLANI PALACE || HAULELAU 2019 A Season of Growth, Change, and Excitement at Iolani Palace 2019–2020 BOARD OF DIRECTORS IOLANI PALACE UNVEILS NEW AUDIO TOUR THE FRIENDS OF IOLANI PALACE 2019 ANNUAL MEMBERSHIP MEETING WELCOME NEW EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR PAULA AKANA CELEBRATING OUR VOLUNTEERS PARTNERSHIPS IN THE COMMUNITY 2019 PALACE ORNAMENT The Friends of Iolani Palace supports, guides, and manages Palace activities, providing caring stewardship for this Hawaiian landmark and national treasure. It currently administers the Palace under a lease with the State of Hawaii. Mrs. Liliuokalani Kawananakoa Morris, grandniece of Queen Kapiolani, founded The Friends of Iolani Palace in 1966. Since that time, The Friends have supported and guided the restoration and management of the Palace building by obtaining donations and grant monies, spearheading efforts to acquire original Palace furnishings, many of which have been scattered throughout the world, and actively managing and assisting with Palace activities. 17793_Iolani_NL_2019Fall.indd 2 8/2/19 5:00 PM A MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR A MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Aloha Friends, I am so happy and humbled to be here at Iolani Palace. portraits in the Palace and wondered who they were I have always loved this very special place, and I look and who painted them, this book is where you will find forward to working with all of you to continue to share its the answers! very important story. Don’t forget to check out our Facebook (@iolanipalace) I would like to send out a sincere mahalo nui loa to Mark and Instagram (@iolanipalacehi), where you will find Shklov, who served as the Interim Executive Director. -

Kathryn EF Shamberger – Curriculum Vitae

Kathryn E. F. Shamberger – Curriculum Vitae Department of Oceanography, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA Office: Eller O&M 911B | Phone: 1-979-845-5752 | Email: [email protected] https://ocean.tamu.edu/people/profiles/faculty/shambergerkathryn.html __________________________________________________________________________ Education 2011 Ph.D. in Chemical Oceanography University of Washington, Seattle, WA. Dissertation title: Calcification, Organic Production, and Carbon Dioxide on a Hawaiian Coral Reef. Advisor: Dr. Richard A Feely 2005 M.S. in Chemical Oceanography University of Hawaii-Manoa, Honolulu, HI. Thesis title: Processes Controlling Air-Sea Exchange of CO2 in Kaneohe Bay, Oahu, Hawaii. Advisor: Dr. Fred T Mackenzie 2001 B.A. in Marine Science, emphasis in Chemistry University of San Diego, San Diego, CA. Graduated with honors __________________________________________________________________________ Positions Held 2014 – current Assistant Professor, Texas A&M University (TAMU) 2013 Postdoctoral Investigator, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution 2011 – 2013 Postdoctoral Scholar, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution 2005 – 2011 Graduate Research Assistant, University of Washington 2003 – 2005 Graduate Research Assistant, University of Hawaii 2002 – 2003 Graduate Teaching Assistant, University of Hawaii 2001 Intern, Center for Tropical Research, Mote Marine Laboratory __________________________________________________________________________ Research Interests Ocean acidification, seawater carbonate -

Manoa's "Puuhonua": the Castle Home, 1900-1941

Manoa's "Puuhonua": The Castle Home, 1900-1941 Peggy Robb and Louise Vicars In our youth we lived in the sloping afternoon shadows of a great Manoa Valley house, which we were told was "the Castle," and we doted on it, imagining crenelations, embrasures, keeps, cellars that could be dun- geons; it was fabulous, and long brassy autos climbed to its fastnesses, perhaps carrying the lost kings and queens of a lost Hawaiian kingdom. We crept in the meadows among cows to spy on what seemed a complete manorial village dropped from the heavens. But "Castle" was really a family name, we came to know. The magic remained—and until central Manoa rilled with competing houses, "Puuhonua" was a glamorous mystery to many a child; it was always part of one's ezva (our western) skyline, transforming a hillside. The Castles of Hawaii were as prodigious as was their house. There is a common and perhaps slightly envious remark in Hawaii that the missionaries came to do good and did well. The Castles did a lot of both. They had a veritable headstart in participating in the financial develop- ment of the Hawaiian kingdom. Samuel Northrup Castle (1808-1894) had been a cashier in a Cleveland, Ohio, bank, then a bookkeeper "in a commercial establishment" when he volunteered for missionary service.1 He arrived as part of the "seventh reinforcement" missionary group in 1837, the seventeenth year of the Protestant Sandwich Isles Mission.2 He was not ordained as a minister. He was to be the "financial agent" for a suddenly expanding Christianity. -

Manoa Heritage Center – Visitor Education Hale Honolulu, HI, USA

Project Name: Manoa Heritage Center – Visitor Education Hale Location: Honolulu, HI, USA Project Narrative: The Visitor Education Hale is the final piece of the Manoa Heritage Center master plan. It will serve as a flexible classroom for the thousands of visitors who come to MHC to experience for the ancient Hawaiian temple, Kuka'o'o heiau and well as the endemic and indigenous collection of Hawaiian plans. It also provides for the MHC administration as well as public restrooms. Please refer to the slides for the complete story about the research, design and execution of the project including a strong emphasis on sustainable design & practices. Sustainability Narrative: Manoa Heritage Center is the caretaker to one of Hawaii's most priced Hawaiian artifacts, Kuka'o'o heiau (temple). Kuka'o'o is an agricultural heiau that is believed to have been constructed during 10th century. Strategically placed in the Waikiki ahupua'a (ancient Hawaiian land division from the mountains to the sea), Kuka'o'o heiau served as a temple for both worship and to study the cosmos related to the Hawaiian lunar calendar which determined the wet & dry seasons as well as the monthly planting & harvesting schedule. Today, Kuka'o'o heiau symbolizes the 600-800 years of sustainable living for ancient Hawaiians prior to western contact and is why sustainability was a major priority for this project. One of our major project goals was to create a Visitor Education Hale with a net zero carbon footprint and provide an educational curriculum for the school children & adult visitors who come to visit MHC. -

The Thirty-First Hawaii State Legislature 2021-2022 Regular Session

The Thirty-First Hawaii State Legislature 2021-2022 Regular Session Hawaii State Representatives and Senators By District Courtesy of the Hawaii Public Access Room (PAR) Phone: (808) 587-0478 Email: [email protected] Website: lrb.hawaii.gov/par Facebook: PublicAccessRoom Twitter: Hawaii_PAR TABLE OF CONTENTS Hawaii Island House of Representative Districts………………………………….…………………………………………………………………….….….3 Senate Districts…………………….……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……..4 Maui, Moloka'i, Lana'i, and Kaho'olawe House of Representative Districts…………………………………………………………………….…………………………………..…….5 Senate Districts………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………..………………..……6 Oahu East Honolulu, House of Representative Districts………………………………………………………………………..………..…...7 Urban Honolulu, House of Representative Districts…………………………………………………………………………………….8 Central, House of Representative Districts…………………………………………………………………………………………..……..9 Ewa Plains/Leeward, House of Representative Districts……………...…..……………………………………………………….10 North Shore/Windward, House of Representative Districts……………………….……………………………………….…….11 Honolulu, Senate Districts………….………………………………………………………….…..……………………………………………..12 Ewa Plains/Leeward, Senate Districts…………………..…………………………………….……………………………………………..13 North Shore/Windward, Senate Districts………………………………………………………………..…………………………….…..14 Kaua'i and Ni'ihau House of Representative and Senate Districts………………………………………………………………………………..…….…..15 Legislative district maps are courtesy of the Hawaii State Office of Planning GIS Program. http://planning.hawaii.gov/gis/ -

Private School Enrollment Report 2020-2021

Private School Enrollment Report 2020-2021 Student Enrollment for the Hawai‘i Private Schools: 2020-2021 School Year 200 N. Vineyard Blvd., Suite 401 • Honolulu HI, 96817 Tel. 808.973.1540 • www.hais.us Table of Contents Hawai‘i Independent School Enrollment Overview .............................................................................................................................. 4 Statewide Overview .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Preschool - Grade 12 Overview .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 By Island ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Oahu ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Neighbor Islands ............................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Special Purpose Schools ................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Honolulu's Parks & Playgrounds: a Brief History

ma M Mala anoa Malama Manoa N E W S L E T T E R Volume 28, No. 1 / Spring 2020 General Membership Meeting – Honolulu’s Parks & Playgrounds: A Brief History by Kiersten Faulkner, Executive Director, Historic Hawai‘i Foundation he history of Ala Moana Park and other historic T parks will be part of a presentation on Honolulu’s Parks and Playgrounds at Mālama Mānoa’s General Membership Japanesemeeting on Seventh-Day Wednesday, Adventist April 8, 2020, at 6:00 p.m. at the Honolulu presentation is free and open to Church (2655 Mānoa Road). The Honoluluthe public. has a rich history of establishing parks, playgrounds and open areas for community Ala Moana Park Banyan Courtyard. Courtesy of HHF. gathering and recreation. Ms. Kiersten Faulkner will give century efforts to establish parks and playgrounds a brief history of urban parks, including the importance of the playground movement and some of the notable landscape and design features in as part of the Free Kindergarten and Children’s Aid historic parks from 1843, through the post-World War II movement. The presentation will also cover key era. landscape and design features from the art deco movement and the importance of the New Deal in Kiersten Faulkner has been the executive director of shaping the parks. The impact of World War II and educationHistoric Hawai‘i and technical Foundation assistance (HHF) forsince historic 2006. preservaHHF is a- its aftermath set theREMINDER stage for parks today. statewide non-profit organization that provides advocacy, Mālama Mānoa Spring tion in the Hawaiian Islands. Kiersten oversees all aspects Membership Meeting of its preservation programs, strategic planning, business lines, and operational matters. -

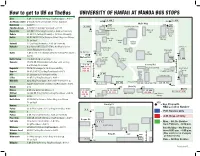

How to Get to UH on Thebus UNIVERSITY of HAWAII at MANOA BUS STOPS

How to get to UH on TheBus UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII AT MANOA BUS STOPS Aiea A OR 11/40/42/53/54/62 to King/Punchbowl > A/4/13 6 80A 6 80A Ala Moana Center 6 Woodlawn/18 on Kona OR A/13 on Kapiolani 865 864 Maile Way Downtown A/4/6/13 4547 4548 13 6 80A 13 Student Services Ewa/Ewa Beach E/42/91/101 to King/Punchbowl > A/4/13 Business Center Adminstration Webster Hawaii Kai 80A OR 1/1L to King/University > A/4/6 on University 809 Hall Kahala 24 OR 1/1L to King/University > A/4/6 on University Moore Hall Kailua 85 OR 56/57/57A to Bishop > A/4 on King, 6 on Bishop, Hamilton George Library 13 on Hotel Hall Hawai’i Hall Varney Kaimuki 1/1L to King/University > A/4/6 on University Circle Kakaako 6 on Queen OR 55/56/57/57A to Ala Moana Center Jefferson Architecture Miller Hall > 6 on Woodlawn/18 on Kona School Kennedy 874 Hall 4 18 85 Art Theater Kalihi A OR C/1/1L/2/2L/9/40/42/43/52/62 to King/Punchbowl > 863 298 6 13 Building A/4/13 Metcalf St. Sinclair Campus 13 6 80A Kalihi Valley 7 to Kalihi/King > A on King Library Center Kaneohe 85/85A OR 55/65/88/88A to Bishop > A/4 on King, 413 4549 6 on Bishop,13 on Hotel 4 6 18 Correa Rd. 80A 83 84 Kuykendall Hall Kapahulu 13/24 (24 changes to 18 at Kapahulu/Olu) 84A 85 Student East-West Center Kapolei 94 OR C/40/102 to King/Punchbowl > A/4/13 85A 90 Health Services East-West Rd.