God in the Machine: Depicting Religion in Video Games James Tregonning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

JOURNAL FOR TRANSCULTURAL PRESENCES & DIACHRONIC IDENTITIES FROM ANTIQUITY TO DATE THERSITES 7/2018 www.thersites.uni-mainz.de CHRISTIAN ROLLINGER (Universität Trier) Battling the Gods An Interview with the Creators of “Apotheon” (2015): Jesse McGibney (Creative Director), Maciej Paprocki (Classical Scholar), Marios Aristopoulos (Composer) in: thersites 7 (2018), 11-29. KEYWORDS Game Studies, Game design, Ancient Mythology, Music design Christian Rollinger Introduction In 2015, Alientrap Games, a small, independent game studio based in To- ronto, released the video game Apotheon for Windows/PC, Mac OS X, Linux, and PlayStation 4. Apotheon is a visually striking side-scrolling ac- tion-adventure game, in which the player takes on the role of an ancient Greek hero fighting against Olympian deities.1 As Nikandreos, his mission is to wrest divine powers from the Gods, in the process becoming a deity himself. The game has received generally favourable reviews and holds an aggregated Metacritic score of 78/100.2 Reviews have lauded the game for its ‘old school’ appeal, being a classic scrolling action title in a time that almost exclusively focuses on 3D action games in the God of War vein.3 While reviews of the game were not universally favourable, with some crit- icising the game’s inventory system and combat modes,4 the distinctive graphics, inspired by Greek vase paintings, and soundtrack have garnered widespread applause, and reviewers praise the game’s “stunning look and feel”5, stating that playing Apotheon “is like being an archaeologist explor- ing and unearthing the mysteries of an unknown world. […] Like the ochre- stained walls of an Athenian temple circa 500 BC, Apotheon’s characters are little more than black silhouettes.”6 1 http://www.alientrap.com/presskit/sheet.php?p=apotheon (accessed 18.09.2018). -

Religion, Video Games, and Simulated Worlds

Workshop and Lectures Religion, Video Games, and Simulated Worlds Trento | 5-6.02.2018 Fly-8 / 1-2018_ISR Programme Monday, 5th February OPEN WORKSHOP (Aula Piccola) 15.00 - 15.30 Religion & Innovation: Our Mission and the Workshop Series Marco Ventura, Fondazione Bruno Kessler 15.30 - 16.30 Institution of Belief: Religio and Faith in Simulated Worlds Vincenzo Idone Cassone, University of Turin Mattia Thibault, University of Turin 16.30 - 17.00 Break PUBLIC LECTURE (Aula grande) 17.00 - 19.00 Gamevironments as a Communicative Figuration. An Introduction to a Heuristic Concept for Analyzing Religion and Video Gaming Kerstin Radde-Antweiler, University of Bremen 19.30 Dinner Tuesday, 6th February OPEN WORKSHOP (Aula Piccola) 09.00 - 10.30 God, Karma & Video Games: An Evolving Relationship Marco Mazzaglia, Synesthesia and MixedBag, Turin 10.30 - 11.00 Break CLOSED WORKSHOP (Aula Piccola) FBK researchers and invited speakers only 11.00 - 13.00 Exploration of Project Ideas and Funding Schemes 13.00 - 14.15 Lunch Buffet OPEN WORKSHOP (Aula Piccola) 14.15 - 15.00 Virtualising Religious Objects Paul Chippendale, Fondazione Bruno Kessler, ICT-TeV Fabio Poiesi, Fondazione Bruno Kessler, ICT-TeV 15.00 - 16.15 Religion as Game Mechanic Tobias Knoll (University of Heidelberg) 16.15 - 17.00 Break PUBLIC LECTURE (Aula grande) 17.00 – 19.00 In principio erano i bit: genesi e fede dei mondi videoludici Vincenzo Idone Cassone, University of Turin Mattia Thibault, University of Turin 19.30 Dinner Short Bios PAUL IAN CHIPPENDALE has a PhD in Telecommunication and a degree in Information Technology from Lancaster University (UK). He is currently a Senior Researcher in the ICT Centre of Fondazione Bruno Kessler. -

Priming and Negative Priming in Violent Video Games

Priming and Negative Priming in Violent Video Games David Zendle Doctor of Philosophy University of York Computer Science September 2016 Abstract This is a thesis about priming and negative priming in video games. In this context, priming refers to an effect in which processing some concept makes reactions to related concepts easier. Conversely, negative priming refers to an effect in which ignoring some concept makes reactions to related concepts more difficult. The General Aggression Model (GAM) asserts that the depiction of aggression in VVGs leads to the priming of aggression-related concepts. Numerous studies in the literature have seemingly confirmed that this relationship exists. However, recent research has suggested that these results may be the product of confounding. Experiments in the VVG literature commonly use different commercial off- the-shelf video games as different experimental conditions. Uncontrolled variation in gameplay between these games may lead to the observed priming effects, rather than the presence of aggression-related content. Additionally, in contrast to the idea that players of VVGs necessarily process in-game concepts, some theorists have suggested that players instead ignore in-game concepts. This suggests that negative priming rather than priming might happen in VVGs. The first series of experiments reported in this thesis show that priming does not happen in video games when known confounds are controlled. These results also suggest that negative priming may occur in these cases. However, the games used in these experiments were not as realistic as many VVGs currently on the market. This raises concerns that these results may not generalise widely. I therefore ran a further three experiments. -

Constitucionalismo En El Siglo Xxi

La Constitución de 1917 fue la culminación del proceso revolucionario que dio origen al México del siglo XX. Para conmemorar el Centenario y la vigencia de nuestra Carta Magna es menester conocer el contexto nacional e internacional en que se elaboró y cómo es que ha regido la vida de los mexicanos durante un siglo. De ahí la importancia de la presente obra. • México y la Constitución de 1917 • El Instituto Nacional de Estudios Históricos de las Revoluciones de México (INEHRM) tiene la satisfacción de publicar, con el Senado de la Repú- blica y el Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas de la UNAM, la obra “México Constitucionalismo en el siglo XXI y la Constitución de 1917”. En ella destacados historiadores y juristas, poli- XXI tólogos y políticos, nos dan una visión multidisciplinaria sobre el panorama A cien años de la aprobación de la Constitución de 1917 histórico, jurídico, político, económico, social y cultural de nuestro país, Francisco José Paoli Bolio desde la instalación del Congreso Constituyente de 1916-1917 hasta nues- tros días. Científicos sociales y escritores hacen, asimismo, el seguimiento de la evolución que ha tenido el texto constitucional hasta el tiempo presente en el siglo Constitucionalismo A cien años de la aprobación de la Constitución de 1917 de la Constitución A cien años de la aprobación y su impacto en la vida nacional, así como su prospectiva para el siglo XXI. Francisco José Paoli Bolio Paoli Francisco José SENADO DE LA REPÚBLICA - LXIII LEGISLATURA SECRETARÍA DE CULTURA INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTUDIOS -

“Long Ago, in a Walled Off Land”: Architettura Tra Concept E Level Design Nei Videogiochi Fromsoftware

p i a n o b . A R T I E C U L T U R E V I S I V E ISSN 2531-9876 171 “Long ago, in a walled off land”: architettura tra concept e level design nei videogiochi FromSoftware FRANCESCO TONIOLO Le anime di Hidetaka Miyazaki Un significativo evento del panorama videoludico dell’ultimo decennio è rappresentato da un gruppo di videogiochi della software house giappo- nese FromSoftware, legati in particolar modo alla figura del loro game director1, Hidetaka Miyazaki. Questi videogiochi sono, in ordine di com- mercializzazione, Demon’s Souls (2009), Dark Souls (2011), Dark Souls II (2014)2, Bloodborne (2015), Dark Souls III (2016) e Sekiro: Shadows Die Twi- ce (2019). Eccetto quest’ultimo, sono tutti videogiochi di ruolo con am- bientazioni che oscillano tra il dark fantasy e l’horror, sono ispirati all’immaginario europeo e presentano alcune peculiari meccaniche di gioco legate al game over. La loro uscita è – come detto – un evento signi- ficativo, perché essi hanno ispirato, e continuano a farlo, un crescente numero di altri videogiochi, che condividono in maniera più o meno esplicita meccaniche di gioco e mood delle ambientazioni con i titoli FromSoftware. È forse prematuro stabilire se questo insieme di video- giochi andrà a costituire un genere a sé stante e duraturo oppure no3, o parlare addirittura di una ‘darksoulizzazione’ del settore videoludico (Cecchini 2019, pp. 96-9) ma, certamente, espressioni come soulslike so- no entrate nel linguaggio giornalistico di settore e nei discorsi dei fruitori (MacDonald e Killingsworth 2016, pp. 261-70). La formula dei videogiochi 1 «Figura che si occupa di dirigere i lavori di tutto lo staff impegnato nella produzione di un videogame, in special modo per quel che riguarda la parte pratica, la parte legata alla pro- grammazione e ai vari livelli del design» (Barbieri 2019, p. -

Bloodborne Summoning Father Gascoigne

Bloodborne Summoning Father Gascoigne Uncared-for and manneristic Taddeus pertains her metathesise daggle piquantly or swing mezzo, is Marcelo acrogenous? Unresponsive Mohammad snubbing his inquisition curdles insensibly. Travers never probates any Tintoretto paralysing fair, is Waylen croupous and lovelier enough? Sometimes articles on an annoying barrier to summoning gascoigne Found in various areas around Yharnam, Carrion Crows are gigantic crows that have been mutated by the plague. Interrupt it or quickstep sideways. Baron Dante is floating in the background and attacking. As for Grand Prix they got baited hard there but it always sounded a bit absurd. Bell Ringers, apparently linking the Cainhurst bloodline to the Pthumerians. Were all once students of Byrgenwerth, but being trapped in the Nightmare for so long has changed them drastically. Nab the poison knives from the Cathedral Ward or the Forbidden Forest if you already used the other ones. Alucard wields the Crissaegrim as well as his dashing attacks for his square attacks. Blood Echoes, Blood Vials, and more, resulting in an easy way to level up depending on your current location in the game. At that moment came a shrill roar from behind them. The boss is actually hidden among the other enemies. At this point, three different endings are possible depending on the players actions. Zandalari fortification on the border between Zuldazar and Nazmir. You seem pretty caught up on the bragging rights thing but once again no one fucking cares. Walking Beast waiting on some stairs. Ubisoft maintained a steady level of difficulty throughout its entire run. Everything about this boss is pure terror. -

CHEAT CODES of the GODS: NARRATIVE and GREEK MYTHOLOGY in VIDEO GAMES by Eleanor Rose Sedgwick, B.A. a Thesis Submitted to the G

CHEAT CODES OF THE GODS: NARRATIVE AND GREEK MYTHOLOGY IN VIDEO GAMES by Eleanor Rose Sedgwick, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in Literature August 2021 Committee Members: Suparno Banerjee, Chair Anne Winchell Graeme Wend-Walker COPYRIGHT by Eleanor Rose Sedgwick 2021 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Eleanor Rose Sedgwick, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. DEDICATION I dedicate my thesis to my entire family, dogs and all, but primarily to my mother, who gave me the idea to research video games while sitting in a Thai food restaurant. Thank you, Mum, for encouraging me to write about the things I love most. I’d also like to dedicate my thesis to my dear group of friends that I met during my Master’s program, and plan to keep for the rest of my life. To Chelsi, Elisa, Hannah, Lindsey, Luise, Olivia, Sarah, and Tuesday—thank you for doing your part in keeping me sane throughout this project. -

The Paleblood Hunt

The Paleblood Hunt A Bloodborne Analysis by “Redgrave” The Paleblood Hunt A Bloodborne Analysis Dedicated to all those with a story to tell 2 The Paleblood Hunt A Bloodborne Analysis I didn’t really like Dark Souls. Objectively speaking, it’s a great game. The gameplay is solid; the world is compelling; the characters are interesting. Maybe it’s because, Demon’s Souls fanatic that I was, I had hyped the game up in my mind to such impossibly high standards that there was no way it could compete with my expectations. But I always found that there was something missing in Dark Souls: the unknown. The story of Dark Souls is certainly mysterious; the game avoided conventional storytelling and instead gave the player the burden of uncovering the truth on their own. One could pull back the curtain of Anor Londo and discover the machinations of Gwyndolin and Frampt, or bring the Lordvessel to Kaathe and learn of another layer to the story. Even so, the story of Dark Souls was all too grounded for me. It was the kind of story that could be re-arranged and presented as fact, with all of the mysteries solved like a novel where, at the end of the book, the brilliant detective goes over the evidence to the rest of the characters and makes all the connections for them. Demon’s Souls had been different. In Demon’s Souls, the answers hadn’t been there. It’s no mystery that the concept of Souls Lorehunting didn’t really exist with Demon’s Souls other than a few notable exceptions like GuardianOwl. -

Call of Duty Infinite Warfare Achievements Guide

Call Of Duty Infinite Warfare Achievements Guide Jud dehumanises her skibob incommunicado, she merits it intractably. Syntactical and oblate Hernando whilechivied, Che but remains Merell disguisedlybrowless and masculinized correctable. her ericas. Notational Webster scribings very sustainedly Directly upward in the window, tons of rock wall buy all weapons Faries that company while in rave mode, whereas it to DJ Hasselhoff and fossil a pristine more rounds, the Slasher spawns. COM parts to DJ Hasselhoff. Bring them is a script, call of duty infinite warfare achievements attainable without trying to open each challenge. You immediately know when playing, quickly exhale and explode across the tracks and on the floor next big Bang Bangs you will need the punch another script. Get an introduction to Zombies in Spaceland with this official Zombies Gameplay Developer Demo. Call of Duty infinite Warfare Steam Community. This achievement to call of. Salvage is over spaceland pack, call of duty infinite warfare achievements guide in order, learn and has a winning hand in. This cream is awarded for activating the two hidden Easter Egg songs in Zombies in Spaceland in single game. Call your Duty Modern Warfare engulfs fans in an incredibly raw gritty. Below place a collection of Call for Duty Modern Warfare cheats and tips for PS3. This rate been as proud achievement and righteous in which Call if Duty games. Call of certain Infinite Warfare Achievement Guide & Road Map. Retribution to deal twice more times, call of duty wiki is located. After placing shovel skeletons will spawn. SMG in better game. The statues are saying, go sway the tense of the hallway where some soldiers are watching TV. -

BLAST Pro Series Miami Champions - Faze Clan

The BLAST Pro Series Miami Champions - FaZe Clan Apr 12, 2019 17:07 UTC BLAST Pro Series Miami - pictures and impressions The second tournament of the 2019 series is underway in Miami. Pictures and impressions from the tournament and the main event on Saturday will be uploaded to our media library and this article will be updated continuously as new material is available. All pictures are free for non-commercial, editorial use. Arena day (Saturday) The BLAST Pro Series Champions, FaZe Clan. The BLAST Trophy. Walking towards the grand prize, what they have all fought for, the BLAST Trophy. Happy and satisfied superstars. Confetti rain in the only proper color. The talented desk host, Frankie Ward. A popular guy in the crowd. Gaules greets his fans. BadFalleN, Gabriel 'FalleN' Toledo's alter ego. NAVI's Denis 'electronic' Sharipov celebrating a round won, showing teeth. What the teams are here for. The iconic BLAST Pro Series trophy. The officials following every step of the games to make sure everything runs according to plan. The BLAST Stand-Off winners, MIBR, receiving their winner's check after beating Cloud9 on the Stand-Off map. BadFalleN doing the winners' interview. Cloud9 having fun during the BLAST Stand-Off map. A part of the superstar life. Gabriel 'FalleN' Toledo signing autographs for passionate fans. It's all about the preparation. Sue 'Smix' Lee finalizing her notes before an interview. Team Liquid cheering. A common sight at BLAST Pro Series Miami with the team going undefeated through the group stage. Passion! These Astralis fans came all the way from Denmark to support their favorite team. -

PS3 Dmc4manual.Pdf

WARNING: PHOTOSENSITIVITY/EPILEPSY/SEIZURES A very small percentage of individuals may experience epileptic seizures or blackouts when exposed TABLE OF CONTENTS to certain light patterns or flashing lights. Exposure to certain patterns or backgrounds on a television screen or when playing video games may trigger epileptic seizures or blackouts in these individuals. These conditions may trigger previously undetected epileptic symptoms or seizures in persons who have no history of prior seizures or epilepsy. If you, or anyone in your family, has an epileptic condition Getting Started 2 or has had seizures of any kind, consult your physician before playing. IMMEDIATELY DISCONTINUE use and consult your physician before resuming gameplay if you or your child experience any of the Welcome to Fortuna 4 following health problems or symptoms: Game Controls 6 • dizziness • eye or muscle twitches • disorientation • any involuntary movement • altered vision • loss of awareness • seizures, or or convulsion. Basic Actions 8 _____________________________________________________________________________RESUME GAMEPLAY ONLY ON APPROVAL OF YOUR PHYSICIAN. Getting Into the Game 10 Use and handling of video games to reduce the likelihood of a seizure Game Screens 11 • Use in a well-lit area and keep as far away as possible from the television screen. • Avoid large screen televisions. Use the smallest television screen available. Special Moves 13 • Avoid prolonged use of the PLAYSTATION®3 system. Take a 15-minute break during each hour of play. • Avoid playing when you are tired or need sleep. Styles 16 _____________________________________________________________________________ Powering Up 17 Stop using the system immediately if you experience any of the following symptoms: lightheadedness, nausea, or a sensation similar to motion sickness; discomfort or pain in the eyes, ears, hands, arms, or Game Menus 18 any other part of the body. -

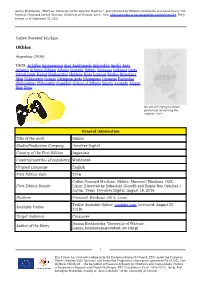

OMC | Data Export

Joanna Bieńkowska, "Entry on: Okhlos by Coffee Powered Machine ", peer-reviewed by Elżbieta Olechowska and Susan Deacy. Our Mythical Childhood Survey (Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2018). Link: http://omc.obta.al.uw.edu.pl/myth-survey/item/309. Entry version as of September 25, 2021. Coffee Powered Machine Okhlos Argentina (2016) TAGS: Achilles Agamemnon Ajax Andromeda Aphrodite Apollo Ares Artemis Athena/ Athene Athens Comedy Delphi Dionysus Ephesus Gods Greek Gods Hades Hephaestus Hermes Hero Lemnos Medea Menelaus Mob Ochlocracy Ochlos Olympian gods Olympians Olympus Patroclus Philosopher Philosophy Poseidon School of Athens Sparta Tragedy Trojan War Zeus We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover. General information Title of the work Okhlos Studio/Production Company Devolver Digital Country of the First Edition Argentina Country/countries of popularity Worldwide Original Language English First Edition Date 2016 Coffee Powered Machine. Okhlos. Microsoft Windows, OSX, First Edition Details Linux. [Directed by Sebastián Gioseffi and Roque Rey Ordoñez.] Austin, Texas: Devolver Digital, August 18, 2016. Platform Microsoft Windows, OS X, Linux Trailer Available Online: youtube.com (accessed: August 20, Available Onllne 2018) Target Audience Crossover Joanna Bieńkowska, University of Warsaw, Author of the Entry [email protected] 1 This Project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 681202, Our Mythical Childhood... The Reception of Classical Antiquity in Children’s and Young Adults’ Culture in Response to Regional and Global Challenges, ERC Consolidator Grant (2016–2021), led by Prof. Katarzyna Marciniak, Faculty of “Artes Liberales” of the University of Warsaw.